Wakulla Springs

| Wakulla Springs | |

|---|---|

|

Wakulla Springs as it empties into the Wakulla River | |

Wakulla Springs Location in Florida | |

| Location | Florida, United States |

| Coordinates | 30°14′01″N 84°18′19″W / 30.23361°N 84.30528°WCoordinates: 30°14′01″N 84°18′19″W / 30.23361°N 84.30528°W |

| Depth | 350 ft (110 m)[1] |

| Length | 31.99 mi (51.48 km)[1] |

| Geology | Limestone |

| Difficulty | Advanced cave diving |

| Cave survey | Woodville Karst Plain Project |

Wakulla Springs is located 14 miles (23 km) south of Tallahassee, Florida and 5 miles (8.0 km) east of Crawfordville in Wakulla County, Florida at the crossroads of State Road 61 and State Road 267. It is protected in the Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park.

Description

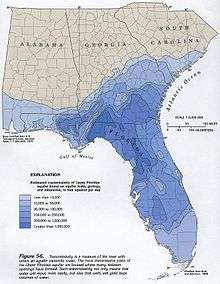

Wakulla cave is a branching flow-dominated cave that has developed in the Floridan Aquifer under the Woodville Karst Plain of north Florida.[2]

It is classified as a first magnitude spring[3][4] and a major exposure point for the Floridan Aquifer. The spring forms the Wakulla River which flows 9 miles (14 km) to the southeast where it joins the St. Mark's River. After a short 5 miles (8.0 km) the St. Mark's empties into the Gulf of Mexico at Apalachee Bay.

History and discovery

Scientific interest in the spring began in 1850, when Sarah Smith reported seeing the bones of an ancient mastodon on the bottom. Since that time, scientists have identified the remains of at least nine other extinct mammals that date to the last glacial period, deposited as far as 1,200 feet (360 m) back into a cave. Today, at a depth of about 190 feet (58 m), the fossilized remains of mastodons are in full view along with other fossils.

The Florida Geological Survey (FGS) commissioned their first study in August and September 1930 with geologist Herman Gunter.[3] Gunter's work focused on the recovery of fossils found in the spring basin. He utilized hard hat diving techniques, a dredge, and "long-handled grappling tongs".[3] A mastodon recovered from their work is now on display at the Museum of Florida History.[3]

The FGS conducted additional studies at Wakulla Springs in 1955, 1956, and 1962 under the direction of vertebrate paleontologist, Stanley J. Olsen.[3][4] Olsen's team of six divers from Florida State University discovered animal fossils deeper within the spring complex where they also found archaeological evidence of early humans, including bone and stone tools. Ultimately, the presumed behavioral association among the recovered cultural and fossil materials could not be demonstrated unequivocally because of the difficulty of establishing and maintaining provenience control in a submerged spring-vent context.[3][4][5]

A major further exploration of Wakulla Springs was conducted in October–December 1987 by an expedition led by Dr. Bill Stone. The expedition team, which also included Sheck Exley and Wesley C. Skiles, penetrated the cave system to a distance of 4,160 feet (1,270 m) from the cave entrance.[6] Skiles filmed the expedition for a National Geographic special.[7] During the expedition Stone's Cis-Lunar Mk-1 rebreather was demonstrated in a 24-hour dive which used only half of the system's capacity.[6][8] In 1998-1999, Stone directed an international group of explorers consisting of over 100 volunteers to participate in the Wakulla 2 Project.[9]

Prehistoric humans

Upper Paleolithic - Paleo-Indians lived at or near the spring over 12,000 years and were descendants of people who crossed into North America from eastern Asia during the Pleistocene. Clovis spear points have been found at Wakulla Springs.

Prehistoric animal life

- American mastodon (Mammut americanum) found at Wakulla.

- Ice Age camel (Camelops hesternus)

- Giant ground sloth (Eremotherium laurillardi)

- Saber-toothed tiger (Smilodon populator) found at Wakulla.

- Columbian mammoth (Mammutus columbi)

- Ancient bison (Bison antiquus)

- Equus (Equus scotti) found near Wakulla.

- Short-faced bear (Arctodus simus)

- Miocene dugong (Metaxytherium crataegense) found near Wakulla.

- American lion (Panthera leo atrox) found in Florida.

Animal life today

Found in and around Wakulla Springs are West Indian manatees, white-tailed deer, North American river otters, American alligators, Suwannee River cooters (Pseudemys suwanniensis), snapping turtles, softshell turtles, limpkin, purple gallinules, herons, egrets, bald eagles, anhingas, ospreys, common moorhens, wood ducks, black vultures and turkey vultures.

Hydrology

Underwater cave system

Wakulla cave consists of a dendritic network of conduits of which 12 miles (19 km) have been surveyed and mapped. The conduits are characterized as long tubes with diameter and depth being consistent (300 ft or 91 m depth); however, joining tubes can be divided by larger chambers of varying geometries. The largest conduit trends south from the spring/cave entrance for over 3.8 miles (6.1 km). Four secondary conduits, including Leon Sinks intersect the main conduit. Most of these secondary conduits have been fully explored.

On December 15, 2007, Woodville Karst Plain Project divers physically connected the Wakulla Springs and Leon Sinks cave systems establishing the Wakulla-Leon Sinks cave system.[2] This connection established the system as the longest underwater cave in the United States[1] and the sixth largest in the world with a total of 31.99 miles (51.48 km) of explored and surveyed passages.[10]

Specifics on flow rate

Flow rate of the spring is 200–300 million US gallons (760,000–1,140,000 m3) of water a day. A record peak flow from the spring on April 11, 1973 was measured at 14,324 US gallons (54,220 L) per second – equal to 1.2 billion US gallons (4,500,000 m3) per day.[11]

Wakulla Springs in film

Beginning in 1938, several of the early Tarzan films including Tarzan's New York Adventure starring Johnny Weissmuller were filmed on location in Wakulla Springs. Other films such as Return of the Creature, Night Moves, Airport '77 and Joe Panther starring Brian Keith and Ricardo Montalbán were also filmed on location at Wakulla Springs.[12]

Most of the movie history can be traced back to Edward Ball (businessman), who purchased the land surrounding Wakulla in 1934.[13] Initially, Wakulla was not a tourist destination, but rather a reclusive resort. This changed when Ball hired a new manager, Newt Perry. Perry is the man who brought publicity to Wakulla Springs. He previously worked at Silver Springs (attraction) and was established in the movie community during his time there. Then, movie crews followed him to Wakulla Springs.

Perry shot a series of underwater short films at Wakulla. One notorious films is What a Picnic!, in which a picnic scene was designed underwater and teenagers would dive down and re-enact a lunch sequence.[14] These underwater films highlighted the aquatic environment that Wakulla Springs offered. Besides these short films, Perry is credited with luring the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Tarzan crews to Wakulla Springs, whose environment would act as a stand in for Africa. Perry previously worked with MGM at Silver Springs (attraction) during the production of Tarzan Finds a Son!.

Grantland Rice also shot scenes from a lesser known movie at Wakulla Springs. Amphibious Fighters (1943) was one of Rice's wartime shorts, which was conveniently produced following the United States entry into World War II.[15] In Amphibious Fighters, the producer Jack Eaton staged a mock battle scene at Wakulla Springs. This battle scene intended to duplicate the real-life conditions soldiers would face when storming the beaches at Normandy circa 1944. Unlike previous Rice films, Amphibious Fighters was not meant to be humorous and would go on to win an Academy Award for Best Short Subject (One-Reel) in 1944.[16]

Recreation

Wakulla Springs Lodge

In 1931, Edward Ball, a businessman from Virginia, bought property in Tallahassee, Florida and construction on the Wakulla Springs Lodge started in 1935. Edward Ball hired the architectural firm, Marsh and Saxelbye, who were based in Jacksonville, Florida and known for their Mediterranean style mansions.[17] Initially, the lodge was built as a guest house and was turned into a hotel after his death in 1981 by the Edward Ball Wildlife Foundation.

The lodge is now a hotel with twenty-seven unique rooms that contain genuine antique furniture. There are two rooms called the Edward Ball Room and the Jessie Ball duPont Room that belonged to Edward Ball and his sister, respectively. In the Edward Ball Room, there is the closet that Edward Ball used to hide his supply of Old Forester Bourbon during Prohibition and during the time Wakulla County was a dry county.[18]

The lobby of the lodge is home to one of the oldest working Art Deco elevators and the largest known marble bar. The use of Tennessee marble is vast in the lobby, decorating baseboards, floors, stairwells, and desktops.[19] The main staircase is made of marble and ironwork. The ironwork railing was forged onsite and feature local wildlife, some of which are life-size.

In 2002, artisans started working to conserve the ceiling of the lodge, funded in part by the State of Florida, Division of Historical Resources and the Historic Preservation Board.[20] Each picture on the 5,800 square-foot ceiling depicts historic Floridian scenes. The techniques are a combination of many, namely European folk art with Native American influences.

Hiking

Wakulla Springs has up to 9 miles of hiking trails throughout it. There are two major trails in the springs. The Cherokee Sink Trail trails around the Cherokee Sink for 1.4 miles. The Cherokee Sink is 80 feet deep and offers a scenic view where you can stop to eat lunch at one of the picnic tables found along the trail. The Bob Rose Trail follows the cave system and starts at the southeast corner of the park. Along the trail, there are dry and wet sinks, swallows, and a collapsed cave.[21]

Boat Tours

Starting from 1875, glass-bottom boat tours have been an attraction at Wakulla Springs. While the glass bottom tours do not occur as often as in previous years due to lack of water clarity, the tours are still held when the water is clear. The tour lasts for 30 minutes and has three afternoon times: 12:00pm, 1:00pm, and 2:00pm. The tour costs $8 for adults (which are people thirteen or older), $5 for children aged three to twelve, and free for children under three.

There is also the River Boat Tour along the Wakulla River. This tour lasts from around 45 minutes to an hour and allows visitors to see an abundance of wildlife. This tour occurs 365 days a year, as long as weather permits. The times of the tour varies but they start at 9:40am and the last one departs at 4:30pm. The cost for the tour is $8 for adults aged thirteen and above, $5 for children aged three to twelve, and free for children under three.[22]

Geo-Seeking

Wakulla Springs allows people to go geocaching in their parks. This just requires the person to bring their own GPS. The participants use their GPS to locate treasure left by others in Wakulla Springs by inputting the coordinates given. Wakulla Springs is part of the Operation Recreation GeoTour. It's a tour that spans from Key West to the Florida panhandle. If someone is one of the first 75 to visit 40 caches, they win a geocoin.

Conservation

The Problem

It came to the attention of conservationists that there was a big problem in late 1998 when populations of the Florida applesnail underwent a drammatic decline, then the iconic Limpkin bird followed suit and left by the fall of 1999. What was once a thriving and diverse ecosystem in North Florida is transitioning into a “biological dessert” says Wakulla Springs conservationist Jim Stevenson The problem is people. Human population increase has rendered grave consequence on our natural surrounding. The Wakulla springs basin stretches about 1,300 miles north of the spring in Florida and even into some of South Georgia. The water pollution from storm water runoff, as well as nitrate rich human water contamination through waste and pollution seeps into the underground aquifer and trickles down and flows out of the Wakulla spring as water at the end of the pipe.

The Solution

Measures have already been taken to lessen the contamination of the spring. The City of Tallahassee has built a Cascades Park that is a wonderful park for citizens masquerading as a state of the art storm water drainage point. This helps reduce the amount of contaminated water entering the basin. The City of Tallahassee has also increased regulations on their wastewater. Though these are huge and impactful remedies, the conscious effort of everyone to reduce their contribution to the contamination will be the biggest aid in not letting Wakulla Springs become nothing more than a memory. Things such as lowering pollution, using less harsh fertilizers, and better waste solutions other than septic tanks that leak enormous amounts of nitrates into the soil, and thus the spring. These solutions will hopefully not only lead to the survival of the springs, but the rejuvenations for generations to come.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wakulla Springs. |

References

- 1 2 3 Bob Gulden (April 24, 2013). "US longest underwater caves". Geo2 Committee on Long and Deep Caves. National Speleological Society (NSS). Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- 1 2 Kernagis DN, McKinlay C, Kincaid TR (2008). "Dive Logistics of the Turner to Wakulla Cave Traverse". In: Brueggeman P, Pollock NW, eds. Diving for Science 2008. Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences 27th Symposium. Dauphin Island, Alabama: AAUS;. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gerrell, Philip R. (1987). "The history and future of archaeological and paleontological work at Wakulla Springs (8WA24)". In: Mitchell, CT (eds.) Diving for Science 86. Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences Sixth Annual Scientific Diving Symposium. Held October 31 - November 3, 1986 in Tallahassee, Florida, USA. American Academy of Underwater Sciences. Retrieved 2013-08-29.

- 1 2 3 Burgess, Robert F. (1999). "Mastodon at Thirty-three Fathoms". The Cave Divers. Locust Valley, New York: Aqua Quest Publications. pp. 85–99. ISBN 1-881652-11-4. LCCN 96-39661.

- ↑ Olsen, S.J. (1959). The Wakulla Cave. In: Cousteau, Jacques-Yves; Dugan, James. Captain Cousteau's Underwater Treasury. Harper & Row. pp. 369–373.

- 1 2 Burgess, Robert F. "Push to the Inner and Outer Limits". The Cave Divers. pp. 118–124.

- ↑ Burgess, Robert F. "Going Where None Have Gone Before". The Cave Divers. pp. 107–117.

- ↑ "History of Scuba". Retrieved 2013-08-29.

- ↑ Kakuk, Brian J. (1999). "The Wakulla 2 Project: Cutting Edge Diving Technology for Science and Exploration.". In: Hamilton RW, Pence DF, Kesling DE, eds. Assessment and Feasibility of Technical Diving Operations for Scientific Exploration. American Academy of Underwater Sciences. Retrieved 2013-08-29.

- ↑ Bob Gulden; Jim Coke (May 13, 2013). "World longest underwater caves". Geo2 Committee on Long and Deep Caves. NSS. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ↑ University of Wyoming: Wakulla Springs

- ↑ Wakulla County.org

- ↑ Hollis, Tim (2006). Glass Bottom Boats & Mermaid Tails: Florida's Tourist Springs. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Book. p. 60.

- ↑ Hollis, Tim (2006). Glass Bottom Boats & Mermaid Tails: Florida’s Tourist Springs. Stackpole Book=Mechanicsburg, PA. p. 63.

- ↑ Hollis, Tim (2006). Glass Bottom Boats & Mermaid Tails: Florida’s Tourist Springs. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole. p. 67.

- ↑ Hollis, Tim (2006). Glass Bottom Boats & Mermaid Tails: Florida’s Tourist Springs. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Book. p. 67.

- ↑

- ↑ http://www.wakullaspringslodge.com/stay

- ↑ http://www.wakullaspringslodge.com/history

- ↑ http://wakullasprings.org/lodge-ceiling-restoration/

- ↑ https://www.floridastateparks.org/park-activities/Wakulla-Springs#Hiking-Nature-Trail

- ↑ https://www.floridastateparks.org/park-activities/Wakulla-Springs#Boat-Tours

External links

- Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park

- Wakulla Spring: A Giant Among Us Interactive Exploration of Wakulla Spring

- St. Marks River and Wakulla Springs Protection - Florida DEP

- Florida's Indians

- Tallahassee Democrat Online Special: Saving Our Springs

- Wakulla Springs and World War II Troop Maneuvers, a video from the 1940s, from the World Digital Library