Virginia opossum

| Virginia opossum[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Metatheria |

| Order: | Didelphimorphia |

| Family: | Didelphidae |

| Subfamily: | Didelphinae |

| Genus: | Didelphis |

| Species: | D. virginiana |

| Binomial name | |

| Didelphis virginiana (Kerr, 1792) | |

| |

| Virginia opossum range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Didelphis marsupialis virginiana[3] | |

The Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana), commonly known as the North American opossum, is the only marsupial found in North America north of Mexico. In the United States, it is typically referred to simply as a possum. It is a solitary and nocturnal animal about the size of a domestic cat. It is a successful opportunist. It is familiar to many North Americans as it is often seen near towns, rummaging through garbage cans, or as roadkill.[4]

Name

The Virginia opossum is the original animal named "opossum". The word comes from Algonquian wapathemwa meaning "white animal". Colloquially, the Virginia opossum is frequently called simply "possum". The name is applied more generally to any of the other marsupials of the Didelphimorphia and order Paucituberculatas, which includes a number of opossum species in South America.

The generic name (Didelphis) is derived from Ancient Greek: di, "two", and delphus, "womb".[5]

The possums of Australia, whose name is derived from a similarity to the Virginia opossum, are also marsupials, but of the order Diprotodontia.

The Virginia opossum is known in Mexico as tlacuache, tacuachi, and tlacuachi, from the Nahuatl word tlacuatzin.

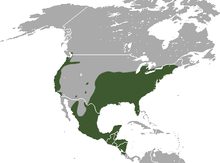

Range

The Virginia opossum is found throughout Central America and North America east of the Rockies from Costa Rica to southern Ontario; it seems to be still expanding its range northward and has been found farther north than Toronto. In recent years, their range has expanded west and north all the way into northern Minnesota. Its ancestors evolved in South America, but invaded North America in the Great American Interchange, which was enabled by the formation of the Isthmus of Panama about 3 million years ago.

The Virginia opossum was not originally native to the Western United States. It was intentionally introduced into the West during the Great Depression, probably as a source of food,[6] and now occupies much of the Pacific coast. Its range has been expanding steadily northward into Canada.

Description

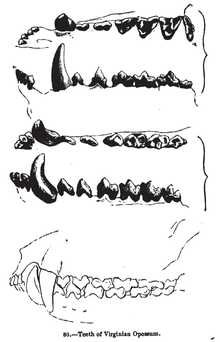

Virginia opossums can vary considerably in size, with larger specimens found to the north of the opossum's range and smaller specimens in the tropics. They measure 13–37 in (35–94 cm) long from their snout to the base of the tail, with the tail adding another 8.5–19 in (21.6–47 cm). Weight for males ranges from 1.7 to 14 lb (0.8–6.4 kg) and for females from 11 ounces to 8.2 lb (0.3–3.7 kg).[7] They are one of the world's most variably sized mammals, since a large male from northern North America weighs about 20 times as much as a small female from the tropics. Their coats are a dull grayish brown, other than on their faces, which are white. Opossums have long, hairless, prehensile tails, which can be used to grab branches and carry small objects. They also have hairless ears and a long, flat nose. Opossums have 50 teeth, more than any other North American land mammal,[8] and opposable, clawless thumbs on their rear limbs.

Opossums have 13 nipples, arranged in a circle of 12 with one in the middle.[9][10]

Perhaps surprisingly for such a widespread and successful species, the Virginia opossum has one of the lowest encephalization quotients of any marsupial.[11] Its brain is one-fifth the size of a raccoon's.[4]

Tracks

Virginia opossum tracks generally show five finger-like toes in both the fore and hind prints.[12] The hind tracks are unusual and distinctive due to the opossum's opposable thumb, which generally prints at an angle of 90° or greater to the other fingers (sometimes near 180°). Individual adult tracks generally measure 1.9 in long by 2.0 in wide (4.8 × 5.1 cm) for the fore prints and 2.5 in long by 2.3 in wide (6.4 × 5.7 cm) for the hind prints. Opossums have claws on all fingers fore and hind except on the two thumbs (in the photograph, claw marks show as small holes just beyond the tip of each finger); these generally show in the tracks. In a soft medium, such as the mud in this photograph, the foot pads clearly show (these are the deep, darker areas where the fingers and toes meet the rest of the hand or foot, which have been filled with plant debris by wind due to the advanced age of the tracks).

The tracks in the photograph were made while the opossum was walking with its typical pacing gait. The four aligned toes on the hind print show the approximate direction of travel.

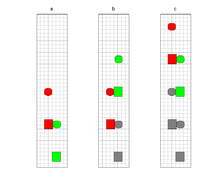

In a pacing gait, the limbs on one side of the body are moved simultaneously, just prior to moving both limbs on the other side of the body. This is illustrated in the pacing diagram, which explains why the left-fore and right-hind tracks are generally found together (and vice versa). However, if the opossum were not walking (but running, for example), the prints would fall in a different pattern. Other animals that generally employ a pacing gait are raccoons, bears, skunks, badgers, woodchucks, porcupines, and beavers.

When pacing, the opossum's 'stride' generally measures from 7 to 10 in, or 18 to 25 cm (in the pacing diagram the stride is 8.5 in, where one grid square is equal to 1 in2). To determine the stride of a pacing gait, measure from the tip (just beyond the fingers or toes in the direction of travel, disregarding claw marks) of one set of fore/hind tracks to the tip of the next set. By taking careful stride and track-size measurements, one can usually determine what species of animal created a set of tracks, even when individual track details are vague or obscured.

Behavior

The Virginia opossum is noted for reacting to threats by feigning death. This is the genesis of the term "playing possum", which means pretending to be dead or injured with intent to deceive. In the case of the opossum, the reaction seems to be involuntary, and to be triggered by extreme fear. It should not be taken as an indication of docility, for under serious threat, an opossum will respond ferociously, hissing, screeching, and showing its teeth, but with enough stimulation, the opossum will enter a near coma. It lies on its side, mouth and eyes open, tongue hanging out, emitting a green fluid from its anus whose putrid odor repels predators. Heart rate drops by half, and breathing rate is slowed by about 30%. Brain activity is unaltered however, and the animal remains fully conscious. Death feigning normally stops when the threat withdraws, and it can last up to six hours. Besides discouraging animals that eat live prey, playing possum also convinces some large animals that the opossum is no threat to their young.

Opossums are omnivorous and eat a wide range of plants and animals such as fruits, grains, insects, snails, earthworms, carrion, snakes, mice, and other small animals. The Virginia opossum has been found to be very resistant to snake venom.[13] Persimmons are one of the opossum's favorite foods during the autumn.[14] Opossums in captivity are known to engage in cannibalism, though this is probably uncommon in the wild.[15] Placing an injured opossum in a confined space with its healthy counterparts is inadvisable.

The Virginia opossum does not hibernate, although it may remain sheltered during cold spells.[16]

Reproduction

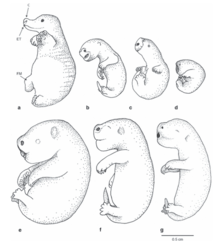

The breeding season for the Virginia opossum can begin as early as December and continue through October with most young born between February and June. A female opossum may have one to three litters per year. During the mating season, the male attracts the female by making clicking sounds with his mouth. Like all female marsupials, the females reproductive system is bifid: with two lateral vaginae, uteri, and ovaries, and the small (comparable to a dime at birth) young are delivered through a birth canal known as the median vagina that forms shortly before birth. The male's penis is also bifid, with two heads, and as is common in American marsupials, the sperm pair up in the testes and only separate as they come close to the egg. It is common for 20 or 30 young to be born (and even as many as 50), but the female only has 13 teats, arranged in a circle with one in the center, so only the first 13 may survive. An average litter is eight or nine joeys, which will reside in their mother's pouch for about two-and-a-half months, before eventually climbing on her back. They leave their mother after about four or five months.[17]

Life span

Opossums, like most marsupials, have unusually short lifespans for their size and metabolic rate. The Virginia opossum has a maximal lifespan in the wild of only about two years.[18] Even in captivity, opossums live only about four years.[19] The rapid senescence of opossums is thought to reflect the fact that they have few defenses against predators; given that they would have little prospect of living very long regardless, they are not under selective pressure to develop biochemical mechanisms to enable a long lifespan.[20] In support of this hypothesis, one population on Sapelo Island, 5 miles (8 km) off the coast of Georgia, which has been isolated for thousands of years without natural predators, was found by Dr. Steven Austad to have evolved lifespans up to 50% longer than those of mainland populations.[20][21]

Historical references

An early description of the opossum comes from explorer John Smith, who wrote in Map of Virginia, with a Description of the Countrey, the Commodities, People, Government and Religion in 1608 that "An Opassom hath an head like a Swine, and a taile like a Rat, and is of the bignes of a Cat. Under her belly she hath a bagge, wherein she lodgeth, carrieth, and sucketh her young."[22][23] The opossum was more formally described in 1698 in a published letter entitled "Carigueya, Seu Marsupiale Americanum Masculum. Or, The Anatomy of a Male Opossum: In a Letter to Dr Edward Tyson," from Mr William Cowper, Chirurgeon, and Fellow of the Royal Society, London, by Edward Tyson, M.D. Fellow of the College of Physicians and of the Royal Society. The letter suggests even earlier descriptions.[24]

Relationship with humans

Like raccoons, opossums can be found in urban environments, where they eat pet food, rotten fruit, and human garbage. Though sometimes mistakenly considered to be rats, opossums are not closely related to rodents. They rarely transmit diseases to humans, and are surprisingly resistant to rabies, mainly because they have lower body temperatures than most placental mammals. In addition, opossums limit the spread of Lyme disease, as they successfully kill off most disease-carrying ticks that feed on them.[25]

The opossum was once a favorite game animal in the United States, in particular in the southern regions which have a large body of recipes and folklore relating to it.[26] Their past wide consumption in regions where present is evidenced by recipes available online[27] and in books such as older editions of The Joy of Cooking.[28] A traditional method of preparation is baking, sometimes in a pie or pastry,[29] though at present "possum pie" most often refers to a sweet confection containing no meat of any kind.

Although it is found throughout the country, the Virginia opossum's appearance in folklore and popularity as a food item has tied it closely to the American Southeast. In animation, it is often used to depict uncivilized characters or "hillbillies". The title character in Walt Kelly's long-running comic strip Pogo was an opossum. In an attempt to create another icon like the teddy bear, President William Howard Taft was tied to the character Billy Possum.[30][31] The character did not do well, as public perception of the opossum led to its downfall. In December 2010, a cross-eyed Virginia opossum in Germany's Leipzig Zoo named Heidi became an international celebrity.[32] She appeared on a TV talk show to predict the 2011 Oscar winners, similar to the World Cup predictions made previously by Paul the Octopus, also in Germany.[33]

References

- ↑ Gardner, A.L. (2005). "Order Didelphimorphia". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Cuarón, A. D.; Emmons, L.; Helgen, K.; Reid, F.; Lew, D.; Patterson, B.; Delgado, C. & Solari, S. (2008). "Didelphis virginiana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- ↑ John J. McManus (July 1970), "Behavior of Captive Opossums, Didelphis marsupialis virginiana", American Midland Naturalist, Vol. 84, No. 1: 144–169, doi:10.2307/2423733 External link in

|title=(help) - 1 2 "Virginia Opossum". Mass Audubon. Retrieved May 11, 2011.

Opossums are frequently encountered as corpses along highways. Some biologists believe that many die as they feed on road-killed animals – a favorite food. Others believe that the opossums’ small brain (5 times smaller than that of a raccoon[sic - erroneous logic]) suggests that they may just be too dumb to get out of the way of vehicles!

- ↑ Day, Leslie (10 May 2013). Field Guide to the Natural World of New York City. JHU Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-4214-1149-1.

- ↑ The Opossum: Its Amazing Story, William J. Krause and Winifred A. Krause, University of Missouri-Columbia, 2006, p. 23, ISBN 0-9785999-0-X, 9780978599904.

- ↑ ADW: Didelphis virginiana: Information. Animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu (1974-05-02). Retrieved on 2011-09-15.

- ↑ Wildlife Directory: Virginia Opossum — Living with Wildlife — University of Illinois Extension. Web.extension.illinois.edu. Retrieved on 2011-09-15.

- ↑ With the Wild Things - Transcripts. Digitalcollections.fiu.edu. Retrieved on 2011-09-15.

- ↑ Mary Stockard, AWRC Mammal Supervisor (2001) Raising Orphaned Baby Opossums. AWRC.org

- ↑ Ashwell, K.w.s. (April 2008). "Encephalization of Australian and New Guinean Marsupials". Brain, Behavior and Evolution. 71 (3): 181–199. doi:10.1159/000114406. ISSN 0006-8977. PMID 18230970.

- ↑ Krause, William J.; Krause, Winifred A. (2006).The Opossum: Its Amazing Story. Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, School of Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri. 80 pages.

- ↑ Sharon A. Jansa; Robert S. Voss (2011). "Adaptive evolution of the venom-targeted vWF protein in opossums that eat pitvipers". PLoS ONE. 6 (6): e20997. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020997. PMC 3120824

. PMID 21731638.

. PMID 21731638. - ↑ Sparano, Vin T. 2000. The Complete outdoors encyclopedia. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-26722-3

- ↑ Cannibalism in the Opossum. Opossum Society. Accessed May 7, 2007.

- ↑ "Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana". eNature.com. Shearwater Marketing Group. Retrieved 2009-03-24.

- ↑ http://opossumsocietyus.org/general-opossum-information/opossum-reproduction-lifecycle/

- ↑ Virginia Opossum. Didelphis virginiana. Great Plains Nature Center. accessed Oct. 15, 2007

- ↑ The Life Span of Animals Accessed Oct. 15, 2007

- 1 2 Karen Wright Staying Alive. Discover Magazine. November 6, 2003 Accessed Oct 15, 2007.

- ↑ http://www.stateoftomorrow.com/stories/aging/austad.htm

- ↑ Chrysti the Wordsmith > Radio Scripts > Opossum. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ↑ Possum History. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ↑ Langworthy, Orthello R. (1932). "The Panniculus Carnosus and Pouch Musculature of the Opossum, a Marsupial". Journal of Mammalogy. 13 (3): 241–251. doi:10.2307/1373999. JSTOR 1373999.

- ↑ Keesing F, Brunner J, Duerr S, Killilea M, LoGiudice K, Schmidt K, Vuong H, Ostfeld RS (2009). "Hosts as ecological traps for the vector of Lyme disease". Proc. R. Soc. B. 276: 3911–3919. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1159.

- ↑ Keith Sutton. Possum days gone by. ESPN Outdoors. January 12, 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ↑ Wild Game Recipes online. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ↑ The joy of the ‘Joy of Cooking,’ circa 1962. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ↑ opossum pie. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ↑ Possum Politics. 'Possum Network. Last accessed November 19, 2006.

- ↑ Political Postcards. Cyberbee learning. Last accessed November 19, 2006.

- ↑ Kelsey, Eric. (January 11, 2011). "Cross-eyed opossum capturing hearts". Reuters. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- ↑ Kelsey, Eric. (28 February 2011). "German celebrity opossum misses one Oscar pick". Reuters. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Didelphis virginiana. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Didelphis virginiana |

- The National Opossum Society

- Opossum Society of the United States

- America Zoo — Opossum

"Virginian Opossum". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

"Virginian Opossum". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.