Victoria Police

- For the Canadian Force see: Victoria Police Department

| Victoria Police | |

|---|---|

|

Patch of the Victoria Police | |

|

Logo of the Victoria Police | |

| Motto |

Uphold the Right Originally written in French as "Tenez le Droit" |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | 8 January, 1853 |

| Employees | 18,146 (30 June 2016) [1] |

| Annual budget | A$2.51 billion (2015–16) [1] |

| Legal personality | Governmental: Government agency |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Operations jurisdiction* | State of Victoria, Australia |

| |

| Victoria Police jurisdiction | |

| Governing body | Government of Victoria |

| Constituting instrument | Victoria Police Act 2013 |

| General nature | |

| Operational structure | |

| Overviewed by | Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (IBAC) (Formerly Office of Police Integrity) |

| Headquarters |

Victoria Police Centre 637 Flinders Street, Docklands, VIC 3008 GPO Box 913 37°49′08″S 144°57′45″E / 37.8189°S 144.9624°ECoordinates: 37°49′08″S 144°57′45″E / 37.8189°S 144.9624°E |

| Sworn members | 14,948 (June 2016) [1] |

| Minister responsible | Lisa Neville, Minister for Police [2] |

| Agency executive | Graham Ashton, Chief Commissioner |

| Units |

List

|

| Regions | Western, Eastern, North West Metro, Southern Metro [3] |

| Facilities | |

| Stations | 329 [4] |

| Website | |

| vicpolicenews.com.au | |

| Footnotes | |

| * Divisional agency: Division of the country, over which the agency has usual operational jurisdiction. | |

Victoria Police is the primary law enforcement agency of Victoria, Australia. It was formed in 1853 and operates under Victoria Police Act 2013.[5][6]

As of 30 June 2016, Victoria Police has over 18,146 sworn members, along with 109 recruits in training, 2 reservists, 1,355 protective services officers and 3,198 civilian staff across 329 police stations. It has a running cost of some A$2.51bn.[1]

Victoria Police enjoys one of the highest community confidence in the world, with more than 86.1% of Victorian residents feeling confident to contact the police. The general satisfaction is also high, with more than 76.9% of the Victorian residents satisfied with policing services in general.[4]

Victoria Police Mission Statement: The Victoria Police mission is to provide a safe, secure and orderly society by serving the community and the law.[7]

History

Early history

The early settlers of Melbourne provided their own Police force and in 1840 there were 12 constables who were paid two shillings and nine pence per day and the chief constable was Mr. W (Tulip) Wright.[8] Charles Brodie followed Wright as chief constable in 1842 and was succeeded by W. J. Sugden who held the positions of 'town chief constable' and superintendent of the local fire brigade.[8] By 1847 there were Police in 'country centres' and the Melbourne force was composed of 'one chief officer, four sergeants, and 20 petty constables'.[8] There was also 'a force of 28 mounted natives' enlisted and trained by DeVilliers and, later, Captain Pulteney Dana.[8]

The Snodgrass Committee was established in early 1852 to "identify the policing needs of the colony" and, following the Committee's report in September 1852, the Victoria Police was formally established on 8 January 1853[9] from an existing colonial police force of 875 men. Later that month William Henry Fancourt Mitchell was 'gazetted as Chief Commissioner of Police for the Colony of Victoria'.[10]

The Port Phillip Native Police Corps was established in Victoria in 1842 and employed aboriginal trackers to carry out duties which included searching for missing persons, carrying messages, and escorting dignitaries through unfamiliar territory.

In 1853, Victoria Police was the first police organisation in Australia who merged all its police entities into one organisation under Victoria Police Chief Commissioner William Mitchell. It remains until this day, that Victoria is the only state in Australia with a Chief Commissioner of Police.[11]

Their first major engagement was the following year, 1854, in support of British soldiers during the events leading up to, and confrontation at, the Eureka Stockade where some miners (mostly Irish), police and soldiers were killed. From a report at the time: 'the troops and Police were under arms, and just at the first blush of dawn they marched upon the camp at Eureka'.[12] Following the brutality of the police after the stockade, public opinion turned against them, the 13 miners charged with treason were all acquitted and police numbers were dramatically cut.

Mitchell resigned as chief commissioner and Charles MacMahon, was appointed acting chief commissioner that same year.[13] After the formation of the Victorian Police, the first recorded death on duty was Edward Gray in 1853, followed by William Hogan in 1854, both of drowning.[14]

The following couple of decades saw the growth of the police force, including the beginning of construction of the Russell Street police station in 1859[15] (site of the later Russell Street Police Headquarters) and the establishment of a special station in William Street to protect the Royal Mint in 1872.

Six years later, three more officers (Kennedy, Lonigan and Scanlan) who were hunting the Kelly Gang, were killed by them at Stringybark Creek.[16][17] Two years later, in 1880, the police confronted the Kelly Gang at Glenrowan. A shoot-out ensued on 28 June, during which three members of the Kelly Gang were killed and following which Ned Kelly was shot and captured.[18]

In 1888 senior constable John Barry produced the first Victoria Police Guide, a manual for officers.[19] (The Victoria Police Manual, as it is now known, remains the comprehensive guide to procedure in the Victoria Police.) Police officers were granted the right to vote in parliamentary elections the same year.[20]

In 1899 the force introduced the Victoria Police Valour Award to recognise the bravery of members.[21] Three years later, in 1902, the right to a police pension was revoked.[22]

1923 Victorian Police strike

On 31 October 1923 members of the Victoria Police Force refused duty and went on strike over the introduction of a new supervisory system. The police strike led to riots and looting in Melbourne's central business district. The Victorian government enlisted special constables, and the Commonwealth of Australia called out the Australian military. Victoria Police are the only Australian police department to ever go on strike.

Only a few of the strikers were ever employed as policemen again, but the government increased pay and conditions for police as a result. Members of the Victoria Police (as its officers are generally known) now have among the highest union membership rates of any occupation, at well over 90%. The Victorian police union, the Police Association, remains a very powerful industrial and political force in Victoria.

Recent history – controversy and corruption allegations

In the 1980s and 1990s allegations were made against most Australian police forces of corruption and graft, culminating in the establishment of several Royal Commissions and anti-corruption watchdogs. Inquiries have also been held into Victoria Police (Beach et al.). The force was criticised because members of the public (both innocent and guilty) were being fatally shot at a rate exceeding that of all other Australian police forces combined.[23] Related criticisms emerged after the 2008 killing of Tyler Cassidy by Victoria Police officers, which was partly blamed on inadequate training. In later years, numerous edits were made to the Wikipedia article about the killing from police computers, in an attempt to give a more favourable impression of the officers' conduct and the subsequent investigation.[24]

In 2001, Christine Nixon was appointed Chief Commissioner, becoming the first woman to head a police force in Australia.

In addition to allegations of corruption among the Uniformed Members of Victoria Police, allegations also surfaced in respect of senior members of the Civil Service serving in Victoria Police. Two motions were raised in the Supreme Court of Victoria. One, Motion 5771/2002 alleged that senior members of Victoria Police divulged the name of a senior Victoria Police Whistleblower to the detriment of his safety. The other, Motion 6337/2002 alleged that the Ombudsman's Office and Auditor General's Office in Victoria had falsified evidence and produced a whitewash report into allegations of corruption in relation to several multimillion-dollar contracts. For reference, these documents may be viewed at the prothonotary's office at the Supreme Court of Victoria in Melbourne.

In June 2003, Taskforce Purana was set up under the command of (then) assistant commissioner Simon Overland to investigate Melbourne's "gangland killings".

In May 2004 former police officer Simon Illingworth appeared on ABC-TV's Australian Story documentary program to tell his disturbing story of entrenched police corruption in Victoria Police. He has also written a book about his experiences entitled Filthy Rat.[25]

In early 2007, Don Stewart, a retired Supreme Court judge, called for a royal commission into Victorian police corruption. Stewart alleged that the force was riddled with corruption that the Office of Police Integrity was unable to deal with.[26]

In early February 2009, in response to evidence that many of the 2009 Victorian bushfires were deliberately lit, chief commissioner Christine Nixon announced the creation of Taskforce Phoenix to investigate all related deaths during the fires, to be led by assistant commissioner Dannye Moloney of the crime department and was composed of around 100 police officers.[27]

On 2 March 2009, Simon Overland was named as the new chief commissioner, replacing Christine Nixon, who was retiring.[28] Simon Overland prematurely resigned on 16 June 2011 with effect from 1 July 2011 over what many assume were the allegations of corruption, the obudsman criticism and the government pressure.[29][30][31]

In November 2011 then acting chief commissioner Ken Lay was named as chief commissioner after five months' caretaking.

On 21 October 2011 the police force evicted Occupy Melbourne protesters from Melbourne City Square. Despite 173 arrests being made, no charges have been laid against any protesters.[32] As the protest continued at other locations through November and December 2011.

On 29 December 2014 Ken Lay announced he was stepping down as the chief commissioner of Victoria Police after three years of service, taking leave until his resignation took effect on 31 January 2015. Deputy chief commissioner Tim Cartwright was acting in the role until a new commissioner was appointed.[33] On 25 May 2015, Deputy Commissioner Graham Ashton of the Australian Federal Police was announced as the new chief commissioner—he took up the role in July 2015.[34]

In April 2016, the treasurer announced an investment of $586m into Victoria Police. From those, $540 million will be used to employ 406 additional sworn police officers and 52 additional specialist staff, technology upgrades and an expanded forensic capability of Victoria Police; $36.8 million to replace and refurbish a number of police stations in regional and rural areas; $19.4 million to continue the Community Crime Prevention Program; $63 million to enhance counter-terrorism capability, including an additional 40 sworn police officers and 48 additional specialist staff to investigate and respond to an increased terror threat. The budget also funds a package of initiatives for all Victoria Police employees to help deal with mental health problems.[35]

In 2015, Victoria Police employed The Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission to examine the nature and prevalence of sex discrimination, including predatory behaviour, amongst Victoria Police personnel.[36] Kate Jenkins was appointed the Commissioner[36] and, in mid December 2015, VEOHRC revealed its findings.[37] Shortly after, on 9 December 2015, Victoria Police Chief Commissioner Graham Ashton apologised over the high tolerance and prevalence of sexual harassment and the sexual discrimination and gender inequality within Victoria Police. Graham Ashton pledged a change of direction and the implementation of all 20 recommendations by VEOHRC.[38]

Uniform history

Between 1853 and 1877, when the first Victoria Police officers emerged, the uniforms resembled the military style of the day. Mounted and foot officers wore dark blue jackets buttoned to the neck. Mounted troops wore swords whilst the Gold Escorts carried revolvers and rifles. The foot patrols, as equipment, had wooden batons notebooks, handcuffs and a whistle to call for assistance when in need. The whistles were fixed to the officer tunic by chain which prevented losing the whistle or falling during a foot chase,[39][40]

In 1877 and until 1947 Victoria Police's uniform resembled British Metropolitan Police's uniform. In 1920, the Wolseley leather "bobby" helmet was also introduced. Policeman were wearing is also wearing striped pieces of cloth (brassards) on their lower left cuffs to show they were on duty. During World War II, Victoria Police issued anti-shrapnel steel helmets, also referred as "tin hats".[39]

Between 1947 and 1979, a major uniform change took place for Victorian Police officers. The bobby helmet was replaced by a black cloth peak cap, a silver police badge was introduced along with white shirts and ties for the general police officers. In 1963, a white pith helmet with a puggaree hatband and a hand-held radio were added to the Victoria Police general duties officers. Along with a new uniform, Victoria Police also introduced the first uniform for women. The uniform for females featured a knee-length skirt, a button-up jacket, a shirt and tie, pantyhose, and peak hats made to fit a lady's hairstyle. Starting with 1972 until 1986, female police officers also carried handbags custom-made to hold batons and firearms.[39][41]

Between 1979 and 2013, police uniforms underwent a number of small changes and there were a total of 83 combinations that a police officer could wear. The changes were mainly as need based for the general duties policing with the addition of capsicum sprays, handgun, baton, etc. In 1981, female police officers were approved trousers as part of their uniform and they were issued 54 pantyhose a year. In 2001, the baseball cap was introduced along with akubra and a woollen jumper. One major change happened in 2008 with the introduction of the Integrated Operational Equipment Vest.[39]

In November 1986, Victoria Police announced the transition of the motto from "Tenez le droit" to "Uphold the right". This change would start taking place in December 1986.[42]

In June 2013, the new dark navy uniform was introduced to all officers as the new standard. The pants are made from rip-stop fabric, the undergarment made from cotton stretch which can be short sleeved or long sleeved and is to be worn under the ballistic vest. Baseball caps remained, although they are darker in colour than pre 2013. The new dark uniform was designed to look more professional and to hide blood, dirt and sweat. The dark blue uniform was modelled after the Oxfordshire and Northumberland police attires.[39]

Rank structure

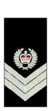

Although Victoria Police has a rank structure similar to an army, the organisation insists it is not a paramilitary organisation.[43] However, within Victoria Police, units such as Special Operations Group, have been identified as paramilitary units by Victoria Police and by Australian Defence Force.[44][45][46][47]

All sworn members start at the lowest rank of constable[48] and work their way up. After their 2 year probationary period, the Constable gets its confirmation and becomes a permanent addition to Victoria Police. The newly confirmed Constable can get the insignia of 'First Constable' to distinguish himself between confirmed and non confirmed Constables.[49]

Constables are promoted in situ to senior constable after two years of becoming a confirmed Constable and successful completion of re-introduced Senior Constable exams. Promotion beyond senior constable is highly competitive. The newly promoted officer is in probation for 1 year.[6]

All Victorian Police members have a rank. There are a total of 13 different ranks within Victoria Police.[50]

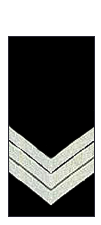

| Rank | Constable | First constable | Senior Constable | Leading senior constable | Sergeant | Senior sergeant |

| Insignia |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Rank | Inspector | Superintendent | Commander | Assistant commissioner | Deputy Commissioner | Chief commissioner |

| Insignia |  |  |  |  |  |  |

Non-commissioned ranks

Promotion to the rank of sergeant and beyond is merit-based. A sergeant normally manages a team during a shift, like Patrol Supervisor of a Police Service Area (PSA) for a shift. A detective sergeant is typically in charge of a team in a specific part of either local detectives at police stations or crime squads.

A senior sergeant oversees the sergeants and traditionally performs more administrative work and middle management duties, for example coordination of policing operations, or specialist work other than active patrol duties. General-duties senior sergeants are traditionally in charge of most police stations or can be a sub-charge (or second in charge) of larger (usually 24-hour) police stations. In each division, or group of divisions on a night shift, a senior sergeant is the division supervisor for a shift and is responsible for managing and overseeing incidents in their area. Detective senior sergeants are usually the officer in charge of crime investigation units.

Designations

Additional classifications are available for members skilful enough, and upon completion of certain training and work-based performances, for classification of detective at senior constable level. detectives also hold classification up to chief superintendent.

Dissolved ranks

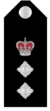

| Rank | Chief Inspector | Chief superintendent |

| Insignia |  |  |

The ranks of chief inspector and chief superintendent are no longer promotable ranks since the changes in hierarchy in 2014.[51]

The previous chief superintendent, Peter McDonald, retired from Victoria Police on 30 September 2014.[52]

Positions

Leading senior constable (LSC) used to be listed in the rank structure but was not a rank per se. It was only open for senior constables to apply for and was not a permanent position. If a member transferred to another duty type or station, the officer was then relieved of the position of LSC. It was primarily a position for field training officers who oversees the training and development of inexperienced probationary constables or constables.

The most recent round of wage negotiations however saw the title of leading senior constable become an actual rank. It is awarded "in situ" but only after assessments have been made against the senior constable's ability to move to the higher position. Leading senior constables are now capable of being upgraded to acting sergeant and it is expected that the position is one that people will move through as they are promoted.

Members who held the position or classification of leading senior constable under the last enterprise bargaining agreements will retain their title and position.

Salaries and benefits

On 15 Feb 2016, Victoria Police members voted for the 2016 - 2019 Enterprise Bargain Agreement. On the 4th of March 2016, the outcome of the vote was announced but the new EB took effect starting on 1 December 2015.[53][54] Under the new EB, Victoria Police officers will receive increased penalty rates for weekend work, added unsociable and intrusive to weekend work, increased pay for prosecutors and a number of other benefits and entitlements.[55] The new EB did not include the ranks of Commanders and above.[55]

On 2016 - 2019 EB, Victoria Police officers were offered 2.5% increase per year for 4 years starting on 1 December 2015. At first, the new proposed agreement was strongly opposed by The Police Association as, in reality, represented only 0.3% increase after inflation.[56][57] However, in December 2015, The Police Association changed their position and supported the new EB.[57][58]

| Rank | Increment | 1 July 2016 | 1 July 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superintendent | 1–8 | $146,257 - $171,580 | $150,279 – $176,298 |

| Inspector | 1–6 | $129,428 - $143,711 | $132,987 - $147,663 |

| Senior sergeant | 1–6 | $109,308 - $116,370 | $112,314 - $119,570 |

| Sergeant | 1–6 | $97,557 - $106,315 | $100,240 - $109,239 |

| Leading senior constable | 13–16 | $91,119 - $95,573 | $93,625 - $98,201 |

| Senior Constable | 5–12 | $82,399 - $90,217 | $84,665 - $92,698 |

| Constable | 1–4 | $$63,757 - $70,968 | $65,510 - $72,920 |

| Recruit | 1 | $46,409 | $47,686 |

| Reservist | 1 | $65,371 | $67,169 |

| Rank | Increment | 1 July 2016 | 1 July 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSO senior supervisor | 1–2 | $86,629 - $87,554 | $89,011 - $89,962 |

| PSO supervisor | 1–4 | $80,071 – $82,996 | $82,273 – $85,278 |

| PSO senior | 1–4 | $67,450 - $72,081 | $69,305 - $74,063 |

| PSO 1st | 5–6 | $63,484 - $65,230 | $65,230 - $67,082 |

| PSO | 1–4 | $58,788 - $62,777 | $60,405 - $64,504 |

| Rank | 1 July 2016 | 1 July 2017 |

|---|---|---|

| Sergeant & senior sergeant | $13,091 | $13,451 |

| Constable & senior constable | $10,430 | $10,717 |

| Rank | 1 July 2016 | 1 July 2017 |

|---|---|---|

| Constable & senior constable | $10,430 | $10,717 |

| Type | Hours | 1 July 2016 | 1 July 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unsociable | 6PM - 1 AM | $5.46 | $5.61 |

| Intrusive | 1AM - 7AM | $6.97 | $7.16 |

| Weekend | 7AM - 6PM | 39.36% of ordinary rate | |

| Unsociable weekend | 6PM - 1AM | 45.22% of ordinary rate | |

| Intrusive weekend | 1AM - 7AM | 57.76% of ordinary rate | |

The arrangement for ordinary hours of work is described in the Victoria Police Force Enterprise Agreement 2011. The ordinary hours of work for full-time members is 80 hours per fortnight arranged within various shifts to suit service delivery needs.[59]

Police officers are entitled to the following[59]:

- nine weeks' leave consisting of:

- five weeks' recreation leave per year

- additional two weeks in lieu of public holidays

- and 10 days accrued time off in lieu of the 38-hour week

- Sick leave of 15 days per year. (accruing)

- A range of other generous leave entitlements; including maternity and paternity leave, study leave and defence force leave.

- Long service leave after seven and a half years of service

- If the police officer is joining the Police Association Victoria (TPAV) they have some other benefits and discounts including (benefits are through TPAV and not related to Victoria Police organisation):[60]

- discounted holiday homes

- discounted car prices for various brands

- access to legal representation

- discounted electricity and gas

Income as a police officer like any member of Victoria Police (employee in Australia) is a taxable income.

Recruits are paid a salary whilst training. During the first 12 weeks, recruits are paid $44,057 per annum. At the end of week 12 when a recruit becomes a (constable) sworn member of Victoria Police is paid $60,526 per annum. Part-time is not available for recruits. Training is ongoing for first two years as a probationary constable. Study leave is available post probationary stage. Further in-house courses and training are available[59]

Head office departments[61]

- Business Services Department

- Corporate Strategy and Operational

- Improvement Department

- Human Resource Department

- Information, Systems and Security Command

- Infrastructure Department

- Intelligence and Covert Support Command

- Legal Services Department

- Licensing and Regulation Division

- Media and Corporate

- Communications Department

- Office of the Chief Commissioner of Police

- Professional Standards Command

- Road Policing Command

- State Emergencies and Security Command

- State Policing Office

- Transit and Public Safety Command

- People Development Command

- Victoria Police Academy

- Crime Command

- Victoria Police Forensic Science Centre

Regional headquarters[61]

- Eastern Region

- North West Metro Region

- Southern Metro Region

- Western Region

Detective branch

Detectives form an integral function in Victoria Police for the detection and investigation of serious crime. Crimes ranging from burglaries and major thefts, serious assaults and now, as a result of the reorganisation of the Crime Department, murder/suicides are just some of the crimes investigated by suburban (divisional) detectives.

Many major police stations, in places such as Prahran, Fawkner, Broadmeadows, Dandenong, Geelong and Melbourne West have a Crime Investigation Unit attached to the station, which looks after crime within those and other neighbouring sub-districts falling within their area.

The State Crime Squads, situated in St Kilda Road, have been recently realigned and contain a number of squads and mini taskforces responsible for the investigation of major drug trafficking activities, major frauds, homicides, armed robbery and firearms trafficking and sex offences to name but a few.

To become a detective in Victoria Police, members must be confirmed senior constables, with at least four years' service, have completed the Field Investigation Course and obtained sufficient experience to sustain the application and interviewing process. Upon obtaining a position at a CIU/Squad, members must then complete the training package (preliminary portfolio of work and course attendance) at the School of Investigation (Detective Training School) to confirm their position as a qualified detective. Detective positions within Victoria Police are highly sought after and awarded, generally, to only the best police applying.

Traditionally, more experienced detectives cut their teeth at divisions and then moved into the crime squads. However the last 10 years has seen a switch in that progression, in that many junior detectives first obtain positions at the sometimes easier to fill Crime Department positions and then later moving onto divisional work. One major reason for this is the travel and often heavy hours involved in working within metropolitan Melbourne.

Media unit

Role of Media Unit

- Advising members of Victoria police on media issues

- Promoting police initiatives, operations and good arrests

- Arranging media conferences

- Preparing media releases

- Monitoring media reports on T.V., radio, online and printed materials

- Attending the scenes which attract media attention

- Helping members of Victoria Police to prepare for media interviews

- Providing information of sub-judice, contempt of court and other media related issues

Although members of Victoria Police are authorised to speak to the media on operational matters directly under their control, prior to speaking with the media, members must advise their superiors of the information they want to release.

Honours and awards

Recognition of the bravery and good conduct of Victoria Police employees is shown through the awarding of honours and decorations. Employees (including both sworn and unsworn personnel) are eligible to receive awards both as a part of the Australian Honours System and the internal Victoria Police awards system.[62]

Australian honours system

Victoria Police employees, like those of their counterparts in other states police forces, are eligible for awards under the Australian Honours System, including:

- Australian Bravery Decorations,[63] namely the Cross of Valour (CV), Star of Courage (SC), Bravery Medal (BM) and the Commendation for Brave Conduct.

- Australian Police Medal[64] – The Australian Police Medal (APM) recognises distinguished service by a sworn police employee and is awarded on Australia Day and Queen's Birthday each year;

- Police Overseas Service Medal[65] – The Police Overseas Service Medal (POSM) recognises service by employees of Australian police forces with international peacekeeping organisations;

- Humanitarian Overseas Service Medal[66] – The Humanitarian Overseas Service Medal (HOSM) honours members of recognised Australian groups that perform humanitarian service overseas in hazardous circumstances;

- National Medal[67] – Available to sworn police employees only, the National Medal (NM) is awarded to specified categories of employees from recognised organisations for diligent service and good conduct over a sustained period. Issued for 15 years service with a clasp issued for each additional 10 years of eligible service;

- Public Service Medal[68] – The Public Service Medal (PSM) is awarded for outstanding public service and is awarded on Australia Day and Queen's Birthday each year;

- Campaign medals such as United Nations Medal For Service, when seconded or attached to an appropriate United Nations position overseas.

Internal Victoria Police honours and awards

| Valour Award | Victoria Police Star | Medal for Excellence | Medal for Courage | Medal for Merit | Service Medal |

- Victoria Police Valour Award – The Victoria Police Valour Award (VA) is awarded to sworn police employees for a particular incident involving an act that displayed exceptional bravery in extremely perilous circumstances;

- Victoria Police Star – The Victoria Police Star is an award for employees killed or seriously injured, on or off duty;

- Victoria Police Medal for Excellence – Awarded to an employee/s who has/have demonstrated a consistent commitment to exceeding the organisational goals and priorities of Victoria Police;

- Victoria Police Medal for Courage – Awarded to an employee/s who has/have performed an act of courage in fulfilment of their duties in dangerous and volatile operational circumstances;

- Victoria Police Medal for Merit – Awarded to an employee/s who has/have demonstrated exemplary service to Victoria Police and the Victorian community;

- Victoria Police Service Medal – The Victoria Police Service Medal (VPSM) is recognition by the chief commissioner of the sustained diligent and ethical service of Victoria Police employees. The medal issued for 10 years service with a clasp issued for each further period of five years' eligible service. Additionally the medal is available to former employees who left Victoria Police before the introduction of the VPSM on 26 February 1996;

- Victoria Police Thirty Five Years Service Award – The Thirty Five Years Service Award recognises employees who have an extensive and dedicated employment history with Victoria Police

- Victoria Police Unit or Group Citation for Courage or Merit – As per the Medal for Courage and/or Medal for Merit criteria;

- Victoria Police Department or Regional Commendation – A department or regional commendation provides recognition of exceptional performance or service;

- Victoria Police Divisional Commendation – A divisional commendation provides recognition of exceptional performance or exceptional service;

- Victoria Police Unit or Group Commendation – a unit or group commendation can be awarded at department, regional or divisional level;

Equipment

Operational and station/office dress

Equipment is carried by officers in a nylon equipment belt, also known as a gun or weapon belt. The nylon belt, specifically designed to be very light-weight, was first issued in 2003 as a replacement for worn leather belts. The belt consists of one firearm holster placed on the hip (either side), one firearm magazine pouch, one ASP (baton) pouch, one OC Spray pouch, one hand cuff pouch and one holder for the portable radio.

Victoria Police started a roll-out of a new uniform design in June 2013 for sworn members, protective service officers reservists and recruits. The new uniform was the first time in over thirty years Victoria Police had significantly changed their uniform, which at the time of replacement could be worn in over eighty different combinations.[69] The new design can be worn in either an operational or station/office dress configuration.

Other holsters can be added to the belt to suit members duties such as a clip to hold the polycarbonate baton or mag light. In 2007/08, the chief commissioner approved the issue of firearm holsters which could be strapped around the members thighs, to replace the low-riding belt gun holster. These holsters are not standard issue but are issued to members upon request, and are commonly requested by members who suffer from back aches (as a result of heavy utility belt), or those who find it more operationally sound to draw their firearms from a lower position (as this option offers a more comfortable reach).

Operational Dress of Victoria Police consists of navy blue cargo/tactical pants, a navy blue long/short sleeved undergarment or shirt, an integrated operational equipment vest (IOEV), a navy blue baseball cap or a wide Brimmed hat (common in rural areas) and black boots. When police members or protective service officers are assigned to duties where they are required to be easily identified, or for occupational health and safety reasons, a high-visibility yellow cover may be put on the IOEV.

Station/office dress consists of navy blue trousers, navy blue long or short sleeved shirts (which can be worn either open-neck or with a tie), navy blue peaked hat and black boots/shoes.

Some specialist units of Victoria Police, such as the Air Wing, Public Order Response Team, Critical Incident Response Team, Search and Rescue Squad and the Special Operations Group, wear uniforms which are customised to their specialist roles.

Firearms

Officers carry the M&P40 semi-automatic pistol as the service pistol to replace the Smith & Wesson Model 10 revolver issued since 1976. They also carry an ASP brand 21-inch expandable baton, Oleoresin Capsicum (OC) Spray and Smith & Wesson brand handcuffs, although there are a number different handcuffs in use. The vast majority of officers carry a Motorola brand tactical radio (with or without handpiece). Other divisions of the Victoria Police have speciality equipment and defensive weapons. The Critical Incident Response Team (CIRT) carries the H&K UMP45 submachinegun (chambered in .40S&W) and Remington 870P 12 gauge shotgun.

The weapons issued to police was a politically contentious issue in the 2006 Victorian state election. A deal between the police union and the state government allocated funding sufficient to cover replacement of the revolvers with semi-automatic pistols, and the equipping of all police cars with tasers, was reached without the involvement of police command.[23] However, despite the allocation of funds in the 2007 state budget, there was initially no indication that the police command had actually decided to purchase the new weapons.[70]

After a violent shootout in Melbourne, during which a man shot a police officer and was shot dead himself, concerns were raised by the Police Association about a possible upgrade to semi-automatic weapons with the $10 million allocated to the police in the 2008–09 Victorian State Budget. Chief Commissioner Christine Nixon launched an inquiry into the fiscal aspect of a possible upgrade. [71]

On 6 June 2008, chief commissioner Christine Nixon announced that an external panel, consisting of a County Court Judge, members of the Australian Defence Force, members of the community, an ethicist and "other professionals" advised that Victoria Police should adopt semi-automatic duty firearms. The chief commissioner had previously announced that she would accept and implement the recommendations of the external panel. She further stated her concerns in regards to semi-automatic firearms, especially if members of the police force required the additional firepower. She believed that there were no incidents she could foresee where general duties members would require the additional ammunition afforded by a semi-automatic duty firearm. In her statement on the Radio 3AW Melbourne she stated that she would like to see the new firearms begin to be issued in about six months.[72]

On 29 April 2010, it was announced that the M&P40 semi-automatic pistol was selected to replace the existing Smith & Wesson Model 10 revolver.[73] Over 10,000 Victoria Police members underwent training and qualification before being issued new pistols.[74]

Victoria Police transport

On 7 March 2014, the Water Police purchased a new state-of-the-art catamaran vessel. The $1.9 million, 14.9-metre-long boat boasts a range of modern technological features and will assist in the search for people stranded at sea or washed overboard and during periods of total darkness, poor light and rough seas. The vessel has the ability to scan the seabed for sunken vessels, and a radar can be switched into heat seeking mode to help locate a person at night, or in situations of poor visibility and rough conditions.[4]

_TX_RWD_wagon%2C_Victoria_Police_(2015-01-06).jpg) 2013 Ford Territory (SZ) TX RWD

2013 Ford Territory (SZ) TX RWD_Evoke_sedan%2C_Victoria_Police_(2015-01-02).jpg) 2014 Holden VF Commodore Evoke

2014 Holden VF Commodore Evoke_Eurocopter_AS-365N-3_Dauphin_2_Vabre-2.jpg) Eurocopter AS365 Dauphin 2

Eurocopter AS365 Dauphin 2 Victoria Police boat docked

Victoria Police boat docked

Training facilities

The main training for Victoria Police during the first 33 weeks, until a member becomes fully operational, is done at Victoria Police Academy.

Academy facility upgrade[4]

In order to increase the Academy's capacity to accommodate the training of an additional 1700 police and 940 PSOs by November 2014, $15.4 million was provided to Victoria Police to upgrade the Victoria Police Academy in 2013–14.

The significant works include:

- an operational tactics and safety training complex with a new firing range, a ‘soft fall’ area for conducted energy device and defensive tactics training, and a simulator, which will be used for firearm and operational safety training, using state-of-the-art bluetooth technology to give recruits the most realistic training experience possible

- a new state-of-the-art training system, called Hydra, which simulates a variety of operational scenarios, ranging from vehicle intercepts to large-scale criminal investigations and emergencies, such as bushfires

- a railway platform for PSO training, new classrooms for training, improvements to bathroom and change room facilities, a dining room upgrade and extra car parking space

New operational tactics and safety training facility[4]

Construction of a new multimillion-dollar police training facility alongside the new Victorian Emergency Management Training Centre in Craigieburn commenced in 2013–14.

The new $30 million Victoria Police OTST facility will replace the existing facility located at Essendon Fields, and is due for completion in March 2015.

The new facility will house administration and training staff and include a specially-designed indoor firing range, scenario training village, classrooms, an auditorium, conference centre and fitness facilities. Police will be required to undertake compulsory training twice a year at the facility.

The close location to the Victorian Emergency Management Training Centre ensures our police officers, fire fighters and the emergency management sector at large will have access to modern training facilities and infrastructure that promote interoperability and allow each agency to grow and adapt to future demands.

Demographics of Victoria Police

| Rank | Males | Females |

|---|---|---|

| Police | 73.7% | 26.3% |

| Recruits | 50.5% | 49.5% |

| Reservists | 25% | 75% |

| PSOs | 90.7% | 9.3% |

| Total sworn | 74.9% | 25.1% |

| Public servants | 32.7% | 67.3% |

| Total workforce | 67.6% | 32.4% |

| Age grouping (years) | Police | Recruits | Reservists | PSOs | Public servants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25 | 3.8% | 31.8% | 13.3% | 5.5% | |

| 25–34 | 26.3% | 44.9% | 41.9% | 26.5% | |

| 35–44 | 31% | 19.6% | 22.5% | 24.1% | |

| 45–54 | 29.6% | 3.7% | 16.7% | 24.8% | |

| 55–64 | 9.1% | 50% | 5.1% | 17% | |

| 65+ | 0.3% | 50% | 0.6% | 2% | |

| Total workforce | 76.1% | 0.6% | 0% | 7.4% | 16.% |

Officers killed on duty

- As of 2013, 157 Victorian Police Officers have died in the line of duty.

- 13 July 1979, Detective Senior Constable Robert Lane was shot and killed while performing a routine interview. Lane was the first officer to be slain on duty since the end of the Vietnam War.[76]

- 27 March 1986, Constable Angela Taylor was killed in the Russell Street Bombing. Taylor was the first female police officer killed in the line of duty in Australian history.[76]

- 12 October 1988, officers Steven Tynan and Damian Eyre were gunned down in the Walsh Street police shootings.[76]

- 16 August 1998, officers Gary Silk and Rodney Miller were gunned down in the Silk–Miller police murders.[76]

Memorials to officers killed on duty are maintained at the Chapel of Remembrance within the main chapel of the Victoria Police Academy at Glen Waverley in the eastern suburbs of Melbourne. There is also a memorial to police officers who have died on duty in Kings Domain, Melbourne, as well as the National Police Memorial in Canberra. Online Honour Rolls are maintained on the Victoria Police website:

See also

- Australian native police

- Victoria Police Special Operations Group

- Victoria Police Search and Rescue Squad

- Victoria Police Air Wing

- Critical Incident Response Team

- Victoria Police Public Order Response Team

- Victoria Police Pipe Band

- Victoria Police Academy

- Corrections Victoria

- Office of Police Integrity

- Project Griffin

- Police misconduct

- Crime in Melbourne

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Annual Report 2015 – 2016". www.police.vic.gov.au. Victoria Police. 2016-10-30. Retrieved 2016-10-30.

- ↑ "Victorian Government Directory". Victorian Government. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ↑ "Victoria Police Boundaries". Victoria Police. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Annual Report 2013-2014". Victoria Police. 30 June 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ↑ "About Victoria Police". Victoria Police. Victoria Police. 16 Oct 2014. Retrieved 30 Aug 2016.

- 1 2 "Victoria Police Act 2013" (PDF). Legislation Victoria. Government of Victoria. 20 April 2016. Retrieved 30 Aug 2016.

- ↑ "Victoria Police Code of Conduct" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 4 Street, B. A. (1954), "Port Phillip – 1840–1850 Part II", Victorian historical magazine, 26 (102): 45, retrieved 29 August 2013

- ↑ Palmer, Darren. A new police in Victoria: conditions of crises or politics of reform? [150 Years of the Victoria Police. Published jointly by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria and the Victoria Police Historical Society.] [online]. Victorian Historical Journal (1987), v.74, no.2, Oct 2003: 167–196. Availability: <http://search.informit.com.au/fullText;dn=200312168;res=APAFT> ISSN 1030-7710. [cited 29 Aug 13].

- ↑ "VICTORIA.". South Australian Register. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 22 January 1853. p. 3. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ↑ 5426_vpo_policelife_winter15_fa_dig

- ↑ "FURTHER PARTICULARS OF THE BALLAARAT AFFRAY.". The Argus. Melbourne: National Library of Australia. 5 December 1854. p. 4. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ↑ Charles MacMahon, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 5, MUP, 1974.

- ↑ "Victoria Police 1800–1899 Honour Roll". Victoria Police. 20 September 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ↑ "Victoria Police History". Victoria Police. 2 December 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ↑ "THE POLICE MURDERS.". The Argus. Melbourne: National Library of Australia. 30 October 1878. p. 6. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ↑ "THE POLICE MURDERS.". The Argus. Melbourne: National Library of Australia. 5 November 1878. p. 6. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ↑ "LATEST NEWS.". The Camperdown Chronicle. National Library of Australia. 29 June 1880. p. 2. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ "THE VICTORIAN POLICE GUIDE.". Bendigo Advertiser. Vic.: National Library of Australia. 20 August 1888. p. 3. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ "Police Franchise.". The Independent. Footscray, Vic.: National Library of Australia. 17 November 1888. p. 2. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ "The Victoria Police Valour Award". Victoria Police historical Society. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ↑ "VICTORIA.". The Chronicle. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 15 November 1902. p. 16. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- 1 2 Murphy, Mathew; Petrie, Andrea; Munro, Ian; Tomazin, Farrah (15 November 2006). "New lethal weapons for police". The Age. Melbourne.

- ↑ Mannix, Liam (1 June 2015). "Victoria Police edits Wikipedia page of police shooting victim Tyler Cassidy". The Age. Melbourne: Fairfax Media. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ Illingworth, Simon (2006). Filthy Rat : One Man's Stand Against Police Corruption and Melbourne's Gangland War (2nd ed.). Fremantle, W.A.: Fontaine Press. ISBN 978-0-9804170-4-3.

- ↑ "Former judge says Vic police are corrupt". The Sydney Morning Herald. 11 January 2007.

- ↑ "PM – Arson taskforce searching for suspects". ABC Online. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ↑ Archived 6 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Overland denies he quit over crime stats". 2011-06-16. Retrieved 2016-08-30.

- ↑ Millar, Paul. "Old-school policeman takes on 'daunting' job". The Age. Retrieved 2016-08-30.

- ↑ McKenzie, Richard Baker and Nick. "Corruption warning over handling of crime stats". The Age. Retrieved 2016-08-30.

- ↑ "Protesters arrested as chaos descends on CBD". The Age. The Age. 22 October 2011.

- ↑ "Victoria Police Chief Commissioner Ken Lay steps down". The Age. Rania Spooner, Tammy Mills. 29 December 2014. Retrieved 2014-12-30.

- ↑ "Graham Ashton appointed Chief Commissioner of Victoria Police". ABC News. 25 May 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ↑ helen.andreou (2016-04-22). "Police". www.budget.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2016-04-29.

- 1 2 "About the review". www.victorianhumanrightscommission.com. Retrieved 2016-08-30.

- ↑ "Human Rights Commission". Human Rights Commission. Human Rights Commission. Dec 2015. Retrieved 30 Aug 2016.

- ↑ "Victoria Police chief apologises over damning sexual harassment findings". 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2016-08-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "From military-style to navy blue threads: the evolution of the Victoria Police uniform". Retrieved 2016-08-31.

- ↑ "Magazine of Victoria Police Uniform History" (PDF). Victoria Police History. Victoria Police Historical Society Inc. 2 Nov 2009. Retrieved 1 Sep 2016.

- ↑ Bucci, Nino. "Dark blue hue a police winner". The Age. Retrieved 2016-08-31.

- ↑ "The Age - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved 2016-08-31.

- ↑ "A VISION FOR VICTORIA POLICE IN 2025". Victoria Police. Victoria Police. May 2014. Retrieved 30 Aug 2016.

- ↑ "Community policing, paramilitary policing and implications for women" (PDF). Australian Institute of Criminology. Australian Institute of Criminology. Retrieved 30 Aug 2016.

- ↑ "Australia's police and military must not become the same thing - On Line Opinion - 15/5/2001". Retrieved 2016-08-30.

- ↑ Jude, McCulloch, (2001-01-01). "Blue army : paramilitary policing in Australia".

- ↑ Jude, McCulloch, (1998-01-01). "Blue army: paramilitary policing in Victoria".

- ↑ "Becoming a Police Officer | About the Role | Police Members | Victoria Police". www.policecareer.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2016-08-30.

- ↑ "The Police Association Victoria - First Constable (63/11)". tpav.org.au. Retrieved 2016-08-30.

- 1 2 3 "Victoria Police - The rank and file". Victoria Police. Victoria Police. 2 Dec 2010. Retrieved 30 Aug 2016.

- ↑ "The rank and file". Victoria Police. State Government Victoria. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ↑ "Victoria Police Association Journal". December 2014.

- ↑ "The Police Association Victoria - EBA ballot timelines announced". tpav.org.au. Retrieved 2016-08-30.

- ↑ "Victoria Police set for a pay boost". Retrieved 2016-08-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Fair Work Commission" (PDF). Fair Work. Fair Work. 21 Mar 2016. Retrieved 30 Aug 2016.

- ↑ "The Police Association Victoria - Why 2.5 Percent is an Insult!". tpav.org.au. Retrieved 2016-08-30.

- 1 2 "Victoria Police pay dispute resolved with four-year deal". 2015-12-10. Retrieved 2016-08-30.

- ↑ "The Police Association Victoria - What the new EB deal means for your Penalty Rates". tpav.org.au. Retrieved 2016-08-30.

- 1 2 3 Victoria Police career webstite

- ↑ "TPAV–The Police Association Victoria".

- 1 2 Victoria Police website

- ↑ Victoria Police Honours & Awards, Victoria Police. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ Australian Bravery Decorations, Awards and Culture Branch, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ Australian Police Medal, Awards and Culture Branch, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ Police Overseas Service Medal, Awards and Culture Branch, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ Humanitarian Overseas Service Medal, Awards and Culture Branch, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ National Medal, Awards and Culture Branch, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ Public Service Medal, Awards and Culture Branch, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ [HS-NewUniform]. 14 June 2013. Retrieved on 15 October 2013.

- ↑ "$273m extra to fight crime". Herald Sun. Australian Associated Press. 1 May 2007.

- ↑ Davis, Michael (15 May 2008). "Police may get semi-automatic guns after shootout". The Australian. News Limited. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ↑ Burgess, Matthew (6 June 2008). "Semi-automatic weapons move a victory, says police union". The Age. Melbourne. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ↑ Millar, Paul (29 April 2010). "Victoria Police switches to semi-automatic weapons". The Age. Melbourne.

- ↑ "Police award tender for semi-automatic firearms". Victoria Police. 29 April 2010. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ↑ "Victoria Police - Annual report 2016". Victoria Police. Victoria Police. Retrieved 2016-10-30.

- 1 2 3 4 "Victoria Police 1950–1999 Honour Roll". Victoria Police. 9 January 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

External links

- Victoria Police website

- Victoria Police news

- Victoria Police Blue Ribbon Foundation

- Victorian Police Association

- Victoria Police Organisational Structure Chart

- Victoria police salaries and penalties 2011 - 2015