United States one hundred-dollar bill

| (United States) | |

|---|---|

| Value | $100 |

| Width | 156 mm |

| Height | 66.3 mm |

| Weight | Approx. 1 g |

| Security features | Security fibers, watermark, 3D security ribbon, optically variable ink, microprinting, raised printing, EURion constellation |

| Paper type |

75% cotton 25% linen |

| Years of printing | 1861–present |

| Obverse | |

| |

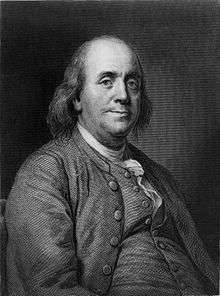

| Design | Benjamin Franklin, Declaration of Independence, quill pen, inkwell |

| Design date | 2009 |

| Reverse | |

| |

| Design | Independence Hall |

| Design date | 2009 |

The United States one hundred-dollar bill ($100) is a denomination of United States currency featuring statesman, inventor, diplomat and American founding father Benjamin Franklin on the obverse of the bill. On the reverse of the banknote is an image of Independence Hall. The $100 bill is the largest denomination that has been printed since July 13, 1969, when the denominations of $500, $1,000, $5,000, and $10,000 were retired.[1] The Bureau of Engraving and Printing says the average life of a $100 bill in circulation is 90 months (7.5 years) before it is replaced due to wear and tear.

The bills are also commonly referred to as "Bens", "Benjamins" or "Franklins", in reference to the use of Benjamin Franklin's portrait on the denomination, or as "C-Notes", based on the Roman numeral for 100. The bill is one of two denominations printed today that does not feature a President of the United States; the other is the $10 bill, featuring Alexander Hamilton. It is also the only denomination today to feature a building not located in Washington, D.C., that being Independence Hall located in Philadelphia on the reverse. The time on the clock of Independence Hall on the reverse, according to the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing, showed approximately 4:10[2] on the older contemporary notes and 10:30 on the series 2009A notes released in 2013.

One hundred hundred-dollar bills are delivered by Federal Reserve Banks in mustard-colored straps ($10,000).

The Series 2009 $100 bill redesign was unveiled on April 21, 2010, and was issued to the public on October 8, 2013.[3] The new bill costs 12.6 cents to produce and has a blue ribbon woven into the center of the currency with "100" and Liberty Bells, alternating, that appear when the bill is tilted.

The $100 bill comprises eighty per cent of all US currency in circulation,[4] although according to former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, more than two-thirds of all $100 notes are held outside the United States.[5]

Large size note history

(approximately 7.4218 × 3.125 in ≅ 189 × 79 mm)

- 1861: Three-year 100 dollar Interest Bearing Notes were issued that paid 7.3% interest per year. These notes were not primarily designed to circulate, and were payable to the original purchaser of the dollar bill. The obverse of the note featured a portrait of General Winfield Scott.

- 1862: The first $100 United States Note was issued. Variations of this note were issued that resulted in slightly different wording (obligations) on the reverse; the note was issued again in Series of 1863.

- 1863: Both one and two and one half year Interest Bearing Notes were issued that paid 5% interest. The one-year Interest Bearing Notes featured a vignette of George Washington in the center, and allegorical figures representing "The Guardian" to the right and "Justice" to the left. The two-year notes featured a vignette of the U.S. treasury building in the center, a farmer and mechanic to the left, and sailors firing a cannon to the right.

- 1863: The first $100 Gold Certificates were issued with a bald eagle to the left and large green 100 in the middle of the obverse. The reverse was distinctly printed in orange instead of green like all other U.S. federal government issued notes of the time.

- 1864: Compound Interest Treasury Notes were issued that were intended to circulate for three years and paid 6% interest compounded semi-annually. The obverse is similar to the 1863 one-year Interest Bearing Note.

- 1869: A new $100 United States Note was issued with a portrait of Abraham Lincoln on the left of the obverse and an allegorical figure representing architecture on the right. Although this note is technically a United States Note, TREASURY NOTE appeared on it instead of UNITED STATES NOTE.

- 1870: A new $100 Gold Certificate with a portrait of Thomas Hart Benton on the left side of the obverse was issued. The note was one-sided.

- 1870: One hundred dollar National Gold Bank Notes were issued specifically for payment in gold coin by participating national gold banks. The obverse featured vignettes of Perry leaving the USS St. Lawrence and an allegorical figure to the right; the reverse featured a vignette of U.S. gold coins.

- 1875: The reverse of the Series of 1869 United States Note was redesigned. Also, TREASURY NOTE was changed to UNITED STATES NOTE on the obverse. This note was issued again in Series of 1878 and Series of 1880.

- 1878: The first $100 silver certificate was issued with a portrait of James Monroe on the left side of the obverse. The reverse was printed in black ink, unlike any other U.S. Federal Government issued dollar bill.

- 1882: A new and revised $100 Gold Certificate was issued. The obverse was partially the same as the Series 1870 gold certificate; the border design, portrait of Thomas H. Benton, and large word GOLD, and gold-colored ink behind the serial numbers were all retained. The reverse featured a perched bald eagle and the Roman numeral for 100, C.

- 1890: One hundred dollar Treasury or "Coin Notes" were issued for government purchases of silver bullion from the silver mining industry. The note featured a portrait of Admiral David G. Farragut. The note was also nicknamed a "watermelon note" because of the watermelon-shaped 0's in the large numeral 100 on the reverse; the large numeral 100 was surrounded by an ornate design that occupied almost the entire note.

- 1891: The reverse of the Series of 1890 Treasury Note was redesigned because the Treasury felt that it was too "busy" which would make it too easy to counterfeit. More open space was incorporated into the new design.

- 1891: The obverse of the $100 Silver Certificate was slightly revised with some aspects of the design changed. The reverse was completely redesigned and also began to be printed in green ink.

- 1914: The first $100 Federal Reserve Note was issued with a portrait of Benjamin Franklin on the obverse and allegorical figures representing labor, plenty, America, peace, and commerce on the reverse.

- 1922: The Series of 1880 Gold Certificate was re-issued with an obligation to the right of the bottom-left serial number on the obverse.

Small size note history

(6.14 × 2.61 in ≅ 157 × 66 mm)

- 1929: Under the Series of 1928, all U.S. currency was changed to its current size and began to carry a standardized design. All variations of the $100 bill would carry the same portrait of Benjamin Franklin, same border design on the obverse, and the same reverse with a vignette of Independence Hall. The $100 bill was issued as a Federal Reserve Note with a green seal and serial numbers and as a Gold Certificate with a golden seal and serial numbers.

- 1933: As an emergency response to the Great Depression, additional money was pumped into the American economy through Federal Reserve Bank Notes issued under Series of 1929. This was the only small-sized $100 bill that had a slightly different border design on the obverse. The serial numbers and seal on it were brown.

- 1934: The redeemable in gold clause was removed from Federal Reserve Notes due to the U.S. withdrawing from the gold standard.

- 1934: Special $100 Gold Certificates were issued for non-public, Federal Reserve bank-to-bank transactions. These notes featured a reverse printed in orange instead of green like all other small-sized notes. The wording on the obverse was also changed to ONE HUNDRED DOLLARS IN GOLD PAYABLE TO THE BEARER ON DEMAND AS AUTHORIZED BY LAW.

- 1950: Many minor aspects on the obverse of the $100 Federal Reserve Note were changed. Most noticeably, the treasury seal, gray numeral 100, and the Federal Reserve Seal were made smaller; also, the Federal Reserve Seal had spikes added around it.

- 1963: Because dollar bills were no longer redeemable in silver, beginning with Series 1963A, WILL PAY TO THE BEARER ON DEMAND was removed from the obverse of the $100 Federal Reserve Note and the obligation was shortened to its current wording, THIS NOTE IS LEGAL TENDER FOR ALL DEBTS, PUBLIC AND PRIVATE. Also, IN GOD WE TRUST was added to the reverse.

- 1966: The first and only small-sized $100 United States Note was issued with a red seal and serial numbers. It was the first of all United States currency to use the new U.S. treasury seal with wording in English instead of Latin. Like the Series 1963 $2 and $5 United States Notes, it lacked WILL PAY TO THE BEARER ON DEMAND on the obverse and featured the motto IN GOD WE TRUST on the reverse. The $100 United States Note was issued due to legislation that specified a certain dollar amount of United States Notes that were to remain in circulation. Because the $2 and $5 United States Notes were soon to be discontinued, the dollar amount of United States Notes would drop, thus warranting the issuing of this note.

- 1990: The first new-age anti-counterfeiting measures were introduced under Series 1990 with microscopic printing around Franklin's portrait and a metallic security strip on the left side of the bill.

- March 25, 1996: The first major design change since 1929 took place with the adoption of a contemporary style layout. The main intent of the new design was to deter counterfeiting. New security features included a watermark of Franklin to the right side of the bill, optically variable ink (OVI) that changed from green to black when viewed at different angles, a higher quality and enlarged portrait of Franklin, and hard-to-reproduce fine line printing around Franklin's portrait and Independence Hall. Older security features such as interwoven red and blue silk fibers, microprinting, and a plastic security thread (which now glows red under a black light) were kept. The individual Federal Reserve Bank Seal was changed to a unified Federal Reserve Seal along with an additional prefix letter being added to the serial number, w. The first of the Series 1996 bills were produced in October 1995.[6]

- February 2007: The first $100 bills (a shipment of 128,000 star notes from the San Francisco FRB) from the Western Currency Facility in Fort Worth, Texas are produced, almost 16 years after the first notes from the facility were produced. The shipment makes the $100 bill the most recently added production to the facility's lineup. 4.6 billion notes were produced at the facility with series 2006 and Cabral-Paulson signatures, including about 4.15 million star notes.[7]

- October 8, 2013: The newest $100 bill was announced on April 21, 2010, and entered circulation on October 8, 2013.[3] In addition to design changes introduced in 1996, the obverse features the brown quill that was used to sign the Declaration of Independence; faint phrases from the Declaration of Independence; a bell in the inkwell that appears and disappears depending on the angle at which the bill is viewed; teal background color; a borderless portrait of Benjamin Franklin; a blue "3D security ribbon" (real name "Motion") on which images of Liberty Bells shift into numerical designations of "100" as the note is tilted; and to the left of Franklin, small yellow 100s whose zeros form the EURion constellation. The reverse features small yellow EURion 100s and has the fine lines removed from around the vignette of Independence Hall. These notes were issued as Series 2009A with Rios-Geithner signatures. Many of these changes are intended not only to thwart counterfeiting but to also make it easier to quickly check authenticity and help vision impaired people.[8]

Both views (obverse and reverse) of the Series 1934 $100 Gold Certificate.

Both views (obverse and reverse) of the Series 1934 $100 Gold Certificate. Front of a Series 1966 $100 United States note.

Front of a Series 1966 $100 United States note. Obverse of a Series 2006A $100 note.

Obverse of a Series 2006A $100 note.

Removal of larger-value bills ($500 and up)

The Federal Reserve announced the removal of large denominations of United States currency from circulation on July 14, 1969. The one-hundred-dollar bill was the largest denomination left in circulation. All the Federal Reserve Notes produced from Series 1928 up to before Series 1969 (i.e. 1928, 1928A, 1934, 1934A, 1934B, 1934C, 1934D, 1950, 1950A, 1950B, 1950C, 1950D, 1950E, 1963, 1966, 1966A) of the $100 denomination added up to $23.1708 billion.[9] Since some banknotes had been destroyed, and the population was 200 million at the time, there was less than one $100 banknote per capita circulating.

As of June 30, 1969, the US coins and banknotes in circulation of all denominations were worth $50.936 billion of which $4.929 billion was circulating overseas.[10] So the currency and coin circulating within the United States was $230 per capita. Since 1969 the demand for U.S. currency has greatly increased. The total amount of circulating currency and coin passed one trillion dollars in March 2011.

Despite the degradation in the value of the U.S. $100 banknote (which was worth more in 1969 than a U.S. $500 note would be worth today), and despite competition from some more valuable foreign notes (most notably, the 500 euro banknote), there are no plans to re-issue banknotes above $100. The widespread use of electronic means to conduct large scale cash transactions today has made large-scale physical cash transactions obsolete and therefore, from the government's point of view, unnecessary for the conduct of legitimate business. Quoting T. Allison, Assistant to the Board of the Federal Reserve System in his October 8, 1998 testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives, Subcommittee on Domestic and International Monetary Policy, Committee on Banking and Financial Services:

There are public policies against reissuing the $500 note, mainly because many of those efficiency gains, such as lower shipment and storage costs, would accrue not only to legitimate users of bank notes, but also to money launderers, tax evaders and a variety of other law breakers who use currency in their criminal activity. While it is not at all clear that the volume of illegal drugs sold or the amount of tax evasion would necessarily increase just as a consequence of the availability of a larger dollar denomination bill, it no doubt is the case that if wrongdoers were provided with an easier mechanism to launder their funds and hide their profits, enforcement authorities could have a harder time detecting certain illicit transactions occurring in cash.[11]

References

- ↑ "For Collectors: Large Denominations". Bureau of Engraving and Printing. Archived from the original on September 11, 2007. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- ↑ "Money Facts". Bureau of Engraving and Printing. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- 1 2 "The Redesigned $100 Note". Bureau of Engraving and Printing. April 21, 2010. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- ↑ Phillips, Matt. "Why the share of $100 bills in circulation has been going up for over 40 years". Quartz. The Atlantic Media Company. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ "Mishap At The Money Factory Delays $100 Bill Release". CBSMiami/CNN. CBS Local Media. 2013-09-06. Retrieved 2013-09-09.

- ↑ USPaperMoney.Info: Series 1996 $100 July 1999

- ↑ USPaperMoney.Info: Series 2006 $100 April 2012

- ↑ uscurrency. "$100 Note Podcast Episode: 1". YouTube. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- ↑ "US Paper Money information: Serial Number Ranges". USPaperMoney.Info. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- ↑ "Some Tables of Historical U.S. Currency and Monetary Aggregates Data" (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- ↑ "Will Jumbo Euro Notes Threaten the Greenback?". U.S. House of Representatives. October 8, 1998. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

Further reading

- Friedberg, Arthur; Ira Friedberg; David Bowers (2005). A Guide Book of United States Paper Money: Complete Source for History, Grading, and Prices (Official Red Book). Whitman Publishing. ISBN 0-7948-1786-6.

- Hudgeons, Thomas (2005). The Official Blackbook Price Guide to U.S. Paper Money 2006 (38th ed.). House of Collectibles. ISBN 1-4000-4845-1. OCLC 244167611.

- Wilhite, Robert (1998). Standard Catalog of United States Paper Money (17th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-653-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 100 United States dollar banknotes. |