United Kingdom and the euro

-

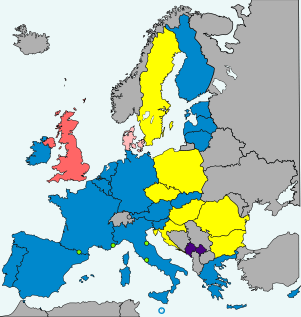

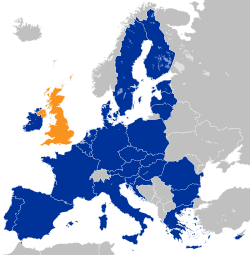

<dt class="glossary " id="European Union (EU) member states" style="margin-top: 0.4em;">European Union (EU) member states

- Non-EU member states

| Part of a series of articles on the |

| United Kingdom in the European Union |

|---|

|

|

Membership

Legislation |

|

The United Kingdom, an EU member state, has not replaced its currency, the pound sterling with the common euro currency. The pound sterling does not participate in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, a prerequisite for euro adoption. The UK negotiated an opt-out from the part of the Maastricht Treaty of 1992 that would have required it to adopt the common currency, and the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government that was elected in May 2010 pledged not to adopt the euro as its currency for the lifetime of the parliament.[1] Polls have shown that the majority of British people are against adopting the euro. In a June 2016 referendum the UK voted to withdraw from the European Union, which if enacted would extinguish any future discussion of it adopting the euro.

History

The United Kingdom entered the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, a prerequisite for adopting the euro, in October 1990. The UK spent over £6 billion trying to keep its currency, the pound sterling, within the narrow limits prescribed by ERM, but was forced to exit the programme within two years after the pound sterling came under major pressure from currency speculators. The ensuing crash of 16 September 1992 was subsequently dubbed "Black Wednesday". During the negotiations of the Maastricht Treaty of 1992 the UK secured an opt-out from adopting the euro.[2]

The government of former Prime Minister Tony Blair declared that "five economic tests" must be passed before the government could recommend the UK joining the euro and promised to hold a referendum on membership if those five economic tests were met. The UK would also have to meet the EU's economic convergence criteria (Maastricht criteria), before being allowed to adopt the euro. Currently, the UK's annual government deficit to the GDP is above the defined threshold. The government committed itself to a triple-approval procedure before joining the eurozone, involving approval by the Cabinet, Parliament, and the electorate in a referendum.

Gordon Brown, Blair's successor, ruled out membership in 2007, saying that the decision not to join had been right for Britain and for Europe.[3] In December 2008, José Barroso, the President of the European Commission, told French radio that some British politicians were considering the move because of the effects of the global credit crisis.[4][5] The office of the Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, denied that there was any change in official policy.[6] In February 2009, Monetary Policy Affairs Commissioner Joaquín Almunia said "The chance that the British pound sterling will join: high."[7]

In the UK general election 2010, the Liberal Democrats increased their share of the vote, but lost seats. One of their aims was to see the UK rejoining ERM II and eventually joining the euro,[8] but when a coalition was formed between the Liberal Democrats and the Conservatives, the Liberal Democrats agreed that the UK would not join the euro during this term of government.

Economics

The UK Treasury first assessed five economic tests in October 1997, when it was decided that the UK economy was neither sufficiently converged with that of the rest of the EU, nor sufficiently flexible, to justify a recommendation of membership at that time.

Another assessment was published on 9 June 2003 by Gordon Brown, when he was Chancellor of the Exchequer. Though maintaining the government's positive view on the euro, the report opposed membership because four out of the five tests were not passed. However, the 2003 document also noted the considerable progress of the UK towards satisfying the five tests since 1997, and the desirability of making policy decisions to adapt the UK economy to better satisfy the tests in future. It cited considerable long-term benefits to be gained from eventual, prudently conducted EMU membership.

Some believe that removing the United Kingdom's ability to set its own interest rates would have detrimental effects on its economy. One argument is that currency flexibility is a vital tool and that the sharp devaluation of sterling in 2008 was just what Britain needed to rebalance its economy.[9] Another objection is that many continental European governments have large unfunded pension liabilities. They fear that if Britain adopts the euro, these liabilities could put a debt burden on the British taxpayer,[10] though others have dismissed this argument as spurious.[11]

The entry of the UK into the eurozone would likely result in an increase in trade with the other members of the eurozone.[12] It could also have a stabilising effect on the stock market prices in the UK.[13] A simulation of the entry in 1999 indicated that it would have had an overall positive, though small, effect in the long term on the UK GDP if the entry had been made with the rate of exchange of the pound to the euro at that time. With a lower rate of exchange, the entry would have had more clearly a positive effect on the UK GDP.[14] A 2009 study about the effect of an entry in the coming years claimed that the effect would likely be positive, improving the stability for the UK economy.[15]

One of the underlying issues that stand in the way of monetary union is the structural difference between the UK housing market and those of many continental European countries.[16] Although home ownership in Britain is near the European average, variable rate mortgages are more common, making the retail price index in Britain more influenced by interest rate changes.

An interesting parallel can be seen in the 19th century discussions concerning the possibility of the UK joining the Latin Monetary Union.[17]

The United Kingdom released new coin designs in 2008 following the Royal Mint's biggest redesign of the national currency since decimalisation in 1971. German news magazine Der Spiegel saw this as an indication that the country has no intention of switching to the euro within the foreseeable future.[18] It is however an unwritten convention that the coin designs should be changed every 40 years to keep the coinage fresh.[19]

Euro exchange rate

In June 2003, Gordon Brown stated that the best exchange rate for the UK to join the euro would be around 73 pence per euro.[20] On 26 May 2003 the euro had reached 72.1 pence, a value not exceeded until 21 December 2007.[21] During the final months of 2008, the pound declined in value dramatically against the euro. The euro rose above 80 pence and peaked at 97.855p on 29 December 2008.[22] This compares with its value between March and October 2008, when the value of the euro was about 78 pence, and its value of about 70 pence between April 2003 and August 2007. With the impact of the Global financial crisis of 2008 on the British economy, including failing banks and plunging UK property values,[23] some British analysts stated that adopting the euro was far preferable to any other possible solutions for Britain's economic problems.[24] There was some media discussion about the possibility of adopting the euro. On 29 December 2008, the BBC reported that the euro had reached roughly 97.7p, due to poorer economic forecasts. This report stated that many analysts believed that parity with the euro was only a matter of time.[25]

At that time, some shops in Northern Ireland accepted the euro at parity, causing a large influx of shoppers from across the Irish border. This made some shops the most successful in their company for several weeks.[26][27] Alex Salmond, the then First Minister of Scotland, called for more Scottish businesses to accept the euro to encourage tourism from the eurozone, noting that this is already done by organisations such as Historic Scotland.[28]

During 2009, the value of the euro against the pound fluctuated between 96.1p on 2 January and 84.255p on 22 June. In 2010 the value of the euro against the pound fluctuated between 91.140p on 10 March and 81.040p on 29 June. On 31 December 2010 the euro closed at 86.075p.[29][30][31][32][33] A report in Britain's Daily Telegraph argued that the high euro had caused problems in the eurozone outside Germany.

There was a fairly steady decline in the euro rate during 2013, 2014 and 2015 from 85p to 70p. During 2016 the pound declined against several currencies, meaning the euro rose. Especially on 24 June 2016 (because of the EU referendum) when the euro rose from 76p to 82p and further the following days.[34]

Convergence criteria

Aside from approval in a domestic referendum , the UK would be required to meet the euro convergence criteria before being granted approval to adopt the euro. As of the last report by the European Central Bank in June 2016, the UK met 2 of 5 of the criteria.

| Convergence criteria | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment month | Country | HICP inflation rate[35][nb 1] | Excessive deficit procedure[36] | Exchange rate | Long-term interest rate[37][nb 2] | Compatibility of legislation | ||

| Budget deficit to GDP[38] | Debt-to-GDP ratio | ERM II member[39] | Change in rate[40][41][nb 3] | |||||

| 2012 ECB Report[nb 4] | Reference values | Max. 3.1%[nb 5] | Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2011)[43] | |||||

| |

4.3% | Open | No | -1.2% | 2.49% | Unknown | ||

| 8.3% | 85% | |||||||

| 2013 ECB Report[nb 8] | Reference values | Max. 2.7%[nb 9] | Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2012)[46] | |||||

| |

2.6% | Open | No | 6.6% | 1.62% | Unknown | ||

| 6.3% | 90.0% | |||||||

| 2014 ECB Report[nb 10] | Reference values | Max. 1.7%[nb 11] | Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2013)[49] | |||||

| |

2.2% | Open | No | -4.7% | 2.25% | Unknown | ||

| 5.8% | 90.6% | |||||||

| 2016 ECB Report[nb 12] | Reference values | Max. 0.7%[nb 13] | Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2015)[52] | |||||

| |

0.1% | Open | No | 10.0% | 1.8% | Unknown | ||

| 4.4% | 89.2% | |||||||

- Notes

- ↑ The rate of increase of the 12-month average HICP over the prior 12-month average must be no more than 1.5% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the similar HICP inflation rates in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these 3 states have a HICP rate significantly below the similarly averaged HICP rate for the eurozone (which according to ECB practice means more than 2% below), and if this low HICP rate has been primarily caused by exceptional circumstances (i.e. severe wage cuts or a strong recession), then such a state is not included in the calculation of the reference value and is replaced by the EU state with the fourth lowest HICP rate.

- ↑ The arithmetic average of the annual yield of 10-year government bonds as of the end of the past 12 months must be no more than 2.0% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the bond yields in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these states have bond yields which are significantly larger than the similarly averaged yield for the eurozone (which according to previous ECB reports means more than 2% above) and at the same time does not have complete funding access to financial markets (which is the case for as long as a government receives bailout funds), then such a state is not be included in the calculation of the reference value.

- ↑ The change in the annual average exchange rate against the euro.

- ↑ Reference values from the ECB convergence report of May 2012.[42]

- ↑ Sweden, Ireland and Slovenia were the reference states.[42]</ref>

(as of 31 Mar 2012) ited Kingdom general election None open (as of 31 March 2012) as its currency for the life Min. 2 years

(as of 31 Mar 2012) _politics/election_2010/86766 Max. ±15%[nb 6]

(for 2011) st adopting the euro. In a [ Max. 5.80%[nb 7]

(as of 31 Mar 2012) t e programme within two years Max. 3.0%

(Fiscal year 2011)<ref name='EC Spring Forecast 2012'>"European economic forecast - spring 2012" (PDF). European Commission. 1 May 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2012. - 1 2 3 4 The maximum allowed change in rate is ± 2.25% for Denmark.

- ↑ Sweden and Slovenia were the reference states, with Ireland excluded as an outlier.[42]</ref>

(as of 31 Mar 2012) ing the euro. ==History== Th Yes<ref>"Convergence Report - 2012" (PDF). European Commission. March 2012. Retrieved 2014-09-26. - ↑ Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2013.[44]

- 1 2 Sweden, Latvia and Ireland were the reference states.[44]</ref>

(as of 30 Apr 2013) that was [[United Kingdom gen None open (as of 30 Apr 2013) adopt the euro as its curren Min. 2 years

(as of 30 Apr 2013) c.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/elec Max. ±15%[nb 6]

(for 2012) ple]] are against adopting th Max. 5.5%[nb 9]

(as of 30 Apr 2013) he UK voted to withdraw from Yes[45]

(as of 30 Apr 2013) il ion trying to keep its curren Max. 3.0%

(Fiscal year 2012)<ref name='EC Spring Forecast 2013'>"European economic forecast - spring 2013" (PDF). European Commission. February 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2014. - ↑ Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2014.[47]

- 1 2 Latvia, Portugal and Ireland were the reference states.[47]</ref>

(as of 30 Apr 2014) [[United Kingdom general elec None open (as of 30 Apr 2014) e euro as its currency for th Min. 2 years

(as of 30 Apr 2014) /hi/uk_politics/election_2010 Max. ±15%[nb 6]

(for 2013) against adopting the euro. Max. 6.2%[nb 11]

(as of 30 Apr 2014) ed to withdraw from the [[Eur Yes[48]

(as of 30 Apr 2014) yi g to keep its currency, the [ Max. 3.0%

(Fiscal year 2013)<ref name='EC Spring Forecast 2014'>"European economic forecast - spring 2014" (PDF). European Commission. March 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014. - ↑ Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2016.[50]

- 1 2 Bulgaria, Slovenia and Spain were the reference states.[50]</ref>

(as of 30 Apr 2016) [[United Kingdom general elec None open (as of 18 May 2016) e euro as its currency for th Min. 2 years

(as of 18 May 2016) /hi/uk_politics/election_2010 Max. ±15%[nb 6]

(for 2015) against adopting the euro. Max. 4.0%[nb 13]

(as of 30 Apr 2016) ed to withdraw from the [[Eur Yes[51]

(as of 18 May 2016) b llion trying to keep its curr Max. 3.0%

(Fiscal year 2015)<ref name='EC Spring Forecast 2016'>"European economic forecast - spring 2016" (PDF). European Commission. May 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

Non-economic factors

Some eurosceptics believe the single currency is merely a stepping stone to a unified European superstate which they strongly reject, or argue against it on other grounds. In December 2008, bookmakers were offering odds-on bets that the United Kingdom would adopt the euro by 2014.[56]

Sterling zone

If the United Kingdom were to join the eurozone, this would affect the Crown dependencies and some British overseas territories that also use the pound sterling, or which have a currency on a par with sterling. In the Crown Dependencies, the Isle of Man, Jersey, Guernsey, and Alderney pounds all share the ISO 4217 code GBP. In the British Overseas Territories, the Gibraltar, Falkland Islands, British Indian Ocean Territory and Saint Helena pounds are also fixed so that £1 in the local currency equals £1 in sterling. The British Antarctic Territory and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands do not have their own currencies and use the pound sterling.

When France adopted the euro, so did the French overseas departments and territories that used the French franc. The CFP franc, the CFA franc and the Comorian franc, that are used in overseas territories and some African countries, had fixed exchange rates with the French franc, but not at par – for various historical reasons they were worth considerably less, at 1 French franc = 18.2 CFP francs, 75 Comorian francs or 100 CFA francs. The CFA franc and the Comorian franc are linked to the euro at fixed rates with free convertibility maintained at the expense of the French Treasury. The CFP franc is linked to the euro at a fixed rate.

It has been suggested that the sterling zone territories would, in the event of the UK adopting the euro, have four options:

- Enter the eurozone as a non-EU member and issue a distinct national variant of the euro—just as Monaco and the Vatican have done. The EU has only allowed sovereign states to adopt this approach to date. Also, it has demanded that monetary agreements be entered into by non-EU members who wish to issue their own euro coinage, and has prevented Andorra from issuing their own coins until this is resolved. Such agreements, the EU has stated, must include adherence to EU banking and finance regulation.

- Use standard euro coins issued by the UK and other eurozone countries. This may be perceived by some as losing an important symbol of independence.

- Maintain their existing currency, but peg at a fixed rate with the euro. Maintaining a fixed rate against currency speculators can be extremely expensive, as the UK found on Black Wednesday. However, if the UK supports the retention of the fixed rates of these small currencies, it would be so trustworthy that no speculation would take place.

- Adopt a free-floating currency, or a currency fixed to another currency, as the Jersey government has hinted.

Gibraltar is in a different position, as it is within the EU (as part of the UK's membership). If the UK were to adopt the euro it might not be possible to implement an opt-out for Gibraltar. It is unclear whether Gibraltar would be subject to its own referendum or would be included in a UK referendum: Gibraltar votes as a part of the UK in European parliamentary elections.

Banknotes

Some private sector banks in Scotland and Northern Ireland issue banknotes of their own design. The Banking Act, 2008[57] amended the rights of Scottish and Northern Irish banks to produce banknotes. This does not apply in Wales which uses Bank of England notes.

In November 1999, in preparation for the introduction of the euro notes and coins across the eurozone, the European Central Bank announced a total ban on the issuing of banknotes by entities that were not national central Banks ('Legal Protection of Banknotes in the European Union Member States'). A move from sterling to the euro would end the circulation of sub-national banknotes as all euro banknotes of a given denomination have an identical design. However, as national variation is a requisite of euro coins, it remains an option for the Royal Mint to incorporate the symbols of the Home Nations into its designs for the British national sides of euro coinage.

Official use of euro in British overseas territories in Cyprus

The Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia in Cyprus introduced the euro at the same time as Cyprus, on 1 January 2008. Previously, they used the Cypriot Pound. Since the independence of Cyprus, treaties dictate that British territories in Cyprus will have the same currency as the Republic of Cyprus. These are the only places under British control where the euro is legal tender. They do not issue separate euro coins. Following the British vote to withdraw from the EU in June 2016, Ioannis Kasoulides, Foreign Minister of Cyprus, announced that Cyprus wished to have EU citizen privileges remain for these areas if the UK ceases to be a member.[58]

Public opinion

The wording of the question may have varied, but the figures show that the majority of British people have been consistently against adopting the euro.

| Date | YES | NO | Unsure | Number of participants | Held by | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| November 2000 | 18% | 71% | N/A | N/A | BBC | [59] |

| January 2002 | 31% | 56% | N/A | N/A | BBC | [59] |

| 9–10 June 2003 | 33% | 61% | 7% | 1852 | YouGov | [60] |

| 10–15 February 2005 | 26% | 57% | 16% | 2103 | Ipsos MORI | [61] |

| 11–12 December 2008 | 24% | 59% | 17% | 2098 | YouGov | [62] |

| 19–21 December 2008 | 23% | 71% | 6% | 1000 | ICM | [59] |

| 6–9 January 2009 | 24% | 64% | 12% | 2157 | YouGov | [63] |

| 17–18 April 2010 | 21% | 65% | 14% | 1433 | YouGov | [64] |

| 2–4 July 2011 | 8% | 81% | 11% | 2002 | Angus Reid | [65] |

| 9–12 August 2011 | 9% | 85% | 6% | 2700 | YouGov | [66] |

| 10 August 2012 | 6% | 81% | 13% | 2004 | Angus Reid | [67] |

The vote to leave the EU in the June 2016 referendum implies a fortiori a rejection of adopting the Euro currency.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on 17 February 2008, but Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. The two governments began to normalise relations in 2013, as part of the Brussels Agreement. Kosovo has received recognition as an independent state from 110 out of 193 United Nations member states.

References

- ↑ BBC News 'David Cameron and Nick Clegg pledge 'united' coalition'

- ↑ Parliament of the United Kingdom (12 March 1998). "Volume: 587, Part: 120 (12 Mar 1998: Column 391, Baroness Williams of Crosby)". House of Lords Hansard. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ↑ Treneman, Ann (24 July 2007). "Puritanism comes too naturally for 'Huck' Brown". London: The Times. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ↑ "No 10 denies shift in euro policy". BBC. 1 December 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- ↑ EUobserver - Britain closer to euro, Barroso says

- ↑ AFP - Britain says no change on euro after EU chief's claim

- ↑ "UPDATE 1-EU's Almunia: high chance UK to join euro in future". in.reuters.com. 2 February 2009. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

- ↑ Evans-Pritchard, Ambrose (21 December 2009). "The rise of Germany belies the chaos a strong euro is causing". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ↑ "Why Britain Shouldn't Join The Euro Zone". Forbes.com. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ↑ "The Euro and its consequences for the United Kingdom". Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ↑ "Brussels bogey: pensions.(UK MOS skeptical of the European Union worry about unfunded pension liabilities)(Brief Article)". http://www.highbeam.com. Retrieved 2013-09-24. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Exchange rate uncertainty, UK trade and the euro". Applied Financial Economics. 2004. Retrieved 2009-09-15.

- ↑ "The Euro and Stock Markets in Hungary, Poland, and UK". Journal of Economic Integration. 2007. Retrieved 2009-09-15.

- ↑ "What if the UK had Joined the Euro in 1999?" (PDF). papers.ssrn.com. 2005. Retrieved 2009-09-15.

- ↑ "Euro Membership as a U.K. Monetary Policy Option: Results from a Structural Model". NBER Working Paper No. w14894. 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-15.

- ↑ MacLennan, D., Muellbauer, J. and Stephens, M. (1998), ‘Asymmetries in housing and financial market institutions and EMU’, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 14/3, pp. 54–80

- ↑ Einaudi, Luca (2001). European Monetary Unification and the International Gold Standard (1865–1873) (PDF). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924366-2. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ↑ "Make Way for Britain's New Coin Designs". Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ Poulter, Sean (29 June 2009). "Have you a 20p worth £50 in your pocket? Royal Mint error results in undated coins". Daily Mail. London. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ↑ Tempest, Matthew (9 June 2003). "Britain not ready to join euro". London: Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- ↑ "Pound sterling (GBP)". European Central Bank. Retrieved 2009-12-25.

- ↑ "ECB: Euro exchange rates GBP". Ecb.int. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ↑ "ECB official rates against the British pound". ECB. Retrieved 2008-11-19.

- ↑ Hutton, Will (16 November 2008). "It might be politically toxic – but we must join the euro now". London: guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 2008-11-19.

- ↑ "Business | Pound hits new low against euro". BBC News. 29 December 2008. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ↑ Seeking bargains across borders, BBC News 14 October 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ↑ 'Euro tourists' crossing border, BBC News 22 December 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ↑ Salmond in call for euro rethink, BBC News 4 January 2009. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ↑ "ECB official rates against the British pound.". ECB. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- ↑ O'grady, Sean (9 April 2009). "Weak pound heaps food inflation on poorest". The Independent. London. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ↑ "Weak pound triggers unexpected rise in inflation - The Scotsman". Business.scotsman.com. 2009-03-24. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ↑ Steed, Alison (4 November 2009). "Wild sterling fluctuations cost expat pensioners billions". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ↑ Howard, Bob (3 January 2009). "Holidays affected by weak pound". BBC News. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ↑ http://www.xe.com/currencycharts/?from=EUR&to=GBP&view=1Y

- ↑ "HICP (2005=100): Monthly data (12-month average rate of annual change)". Eurostat. 16 August 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ↑ "The corrective arm". European Commission. Retrieved 2014-07-05.

- ↑ "Long-term interest rate statistics for EU Member States (monthly data for the average of the past year)". Eurostat. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ↑ "Government deficit/surplus data". Eurostat. 22 April 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ "What is ERM II?". European Commission. 31 July 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ↑ "Euro/ECU exchange rates - annual data (average)". Eurostat. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ↑ "Former euro area national currencies vs. euro/ECU - annual data (average)". Eurostat. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Convergence Report May 2012" (PDF). European Central Bank. May 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- ↑

- 1 2 "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2013. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ↑ "Convergence Report - 2013" (PDF). European Commission. March 2013. Retrieved 2014-09-26.

- ↑

- 1 2 "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2014. Retrieved 2014-07-05.

- ↑ "Convergence Report - 2014" (PDF). European Commission. April 2014. Retrieved 2014-09-26.

- ↑

- 1 2 "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2016. Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- ↑ "Convergence Report - June 2016" (PDF). European Commission. June 2016. Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- ↑

- ↑ "Luxembourg Report prepared in accordance with Article 126(3) of the Treaty" (PDF). European Commission. 12 May 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ↑ "EMI Annual Report 1994" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). April 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- 1 2 "Progress towards convergence - November 1995 (report prepared in accordance with article 7 of the EMI statute)" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). November 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ↑ "Britain odds-on to adopt euro by 2014". Politics.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ↑ "UK Parliament site". Services.parliament.uk. 1 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ↑ N.N. "FM: Our goal is to secure the status of EU citizens within the British Bases in Cyprus". Famagusta Gazette. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Most Britons 'still oppose euro'". BBC. 1 January 2009. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ↑ "YouGov Survey Results: The Euro" (PDF). Yougov.com. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ "EMU Entry and EU Constitution". Ipsos MORI. 2005. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- ↑ "Welcome to YouGov" (PDF). Yougov.com. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ↑ "Welcome to YouGov" (PDF). Yougov.com. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ↑ "YouGov Survey Results: The Euro" (PDF). Yougov.com. Retrieved 2010-04-20.

- ↑ "AngusReid PublicOpinion" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-09-11.

- ↑ "Bloomberg poll". Retrieved 2011-09-15.

- ↑ "AngusReid PublicOpinion" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-06-27.

External links

- HM Treasury – Official UK Treasury euro website

- European Central Bank – Graph showing euro-sterling exchange-rate from 1999 to the present

- The UK's five tests BBC

- Reuters – Factbox – A look at sterling milestones as euro parity looms

- What has Europe ever done for us? A humorous argument against Eurosceptics