Fishing industry in the United States

|

The USA, including Alaska, has a coastline of 19,900 km. | |

| General characteristics (2004 unless otherwise stated) | |

|---|---|

| EEZ area | 11350000 sq km (4,383,000 sq mi) |

| Lake area | 664,707 sq km[1] |

| Land area | 9,161,923 sq km[1] |

| MPA area | 390,000 sq km (150,000 sq mi)[2] |

| Employment |

Primary: 36,000 (2002)[3] Secondary: 67,472 (2002)[4] |

| Fishing fleet | 19,350 vessels aggregating 1.1 million grt.[5] |

| Landing sites |

Most volume: Dutch Harbor Most value: New Bedford |

| Consumption | 31.0 kg fish per capita (2003)[5] |

| Fisheries GDP | US$ 31.5 billion (2003)[5] |

| Export value | US$ 12.0 billion (2003)[5] |

| Import value | US$ 21.3 billion (2003)[5] |

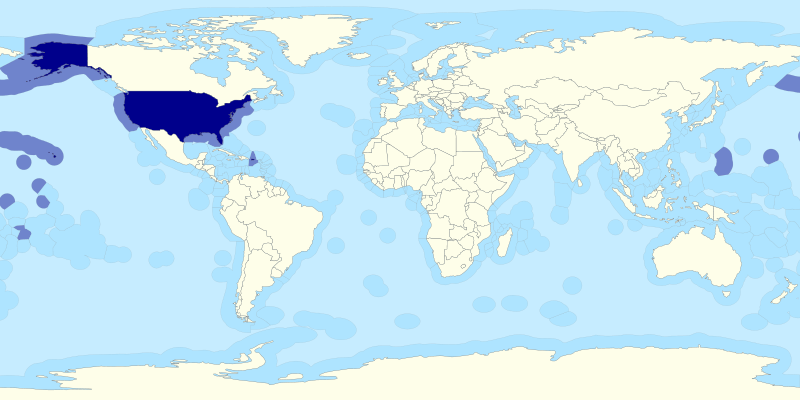

As with other countries, the 200 nautical miles (370 km) exclusive economic zone (EEZ) off the coast of the United States gives its fishing industry special fishing rights.[6] It covers 11.4 million square kilometres (4.38 million sq mi). This is the largest zone in the world, exceeding the land area of the United States.[7]

According to the FAO, in 2005 the United States harvested 4,888,621 tonnes of fish from wild fisheries and another 471,958 tonnes from aquaculture. This made the United States the fifth leading producer of fish after China, Peru, India and Indonesia, with 3.8 percent of the world total.[8]

Management

Historically, fisheries developed in the U.S. as each area was settled. Concern for the sustainability of fishery resources was evident as early as 1871, when Congress wrote that "… the most valuable food fishes of the coast and the lakes of the U.S. are rapidly diminishing in number, to the public injury, and so as materially to affect the interests of trade and commerce...." However, it was not until 1976, with the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, that the federal government began actively managing fisheries.[5]

Today, inland fisheries and nearshore marine fisheries are managed by state (or regional or county) fisheries commissions. State jurisdictions usually extend 3 nautical miles (6 km) out to sea. Coastal fisheries in the EEZ beyond state jurisdictions are the responsibility of the federal system.[5] The primary institutions of the federal system are eight regional fishery management councils and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), also known as NOAA Fisheries.[9] NMFS works in partnership with industry, universities, and state, local, and tribal agencies to collect data about commercial species. Fisheries observers on fishing vessels, transmit real time data electronically to NMFS.[5]

NMFS works in partnership with the regional fishery management councils to prevent overfishing and restore overfished stocks. Objectives are to reduce fishing intensity, monitor the fisheries, and implement measures to reduce bycatch and protect essential fish habitat. NMFS is establishing marine protected areas and individual fishing quotas, and implementing ecosystem based fishery management.[10]

Wild fisheries

EEZ

The U.S. EEZ is the largest in the world, 1.7 times the land area of the US, and includes eight large marine ecosystems:

- Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf

- Southeast U.S. Continental Shelf

- Caribbean Sea

- Gulf of Mexico

- California Current

- Insular Pacific-Hawaiian

- Gulf of Alaska

- Eastern Bering Sea

Catch profile

|

| |

|

|

| Major U.S. domestic species landed[5] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Species 2003 |

Catch million tonnes |

Value $US million |

| Pollock | 1,532 | 209 |

| Menhaden | 727 | |

| Salmon | 306 | 201 |

| Cod | 269 | 187 |

| Flatfish | 202 | 267 |

| Hakes | 155 | |

| Crabs | 154 | 484 |

| Shrimp | 143 | 424 |

| Herring (sea) | 130 | |

| Sardines | 73 | |

| Lobsters | 308 | |

| Scallops | 229 | |

| Clams | 163 | |

| Oysters | 103 | |

| Fisheries data in tons excluding molluscs[5] | |||||

| 2003 | Production | Imports | Exports | Food supply | Per capita[12] kg/year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish for direct human consumption | 3,420,000 | 4,390,000 | 2,450,000 | 5,360,000 | 26.8 |

| Fish for animal feed etc. | 310,000 | 620,000 | 590,000 | 4.2 | |

| Total | 4,320,000 | 4,700,000 | 3,070,000 | 5,950,000 | 31.0 |

Nearshore fisheries

Nearshore fishing areas consist of estuaries and coastal areas that lie within 3 nautical miles (6 km) of the shoreline. These are under the control of the relevant coastal state rather than under federal or NMFS control. They vary widely in species diversity and abundance. Many species are highly prized game fish, while others are small forage fish used for bait, animal food, and industrial products. Those of greatest interest include invertebrate species like crabs, shrimps, abalones, clams, oysters and scallops. Many species are of unknown status because it is difficult to assess their condition. There are no firm estimates exist for long term potential yield.[5]

Management is spread out among the coastal states and other local authorities, and a comprehensive treatment of the fisheries has not been attempted. Traditional techniques are usually employed, including size limits, catch limits, method restrictions, and area and time closures.[5]

Coastal fisheries

The coastal fisheries are the fisheries that lie within 200 nautical miles (370 km) of the coast that defines the exclusive economic zone, but outside the 3 nautical miles (6 km) distance that defines the nearshore fisheries. Coastal fisheries are under federal control in the form of NMFS, as well as under the control of one of the eight regional fishery management councils

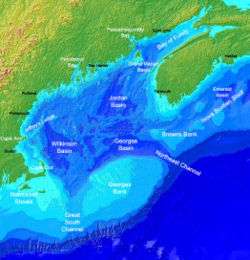

Northeast

Traditionally the most valued fishery for the northeast region has been groundfish. However, the groundfish, especially haddock, yellowtail flounder and cod have been overfished. Record low spawning biomass levels occurred in 1993–94, though these are now recovering. Dogfish and skate rebounded in the 1970s while groundfish and flounder declined. These fish are an important part of the Georges Bank.[5]

The next most important fishery by value is American lobster and Atlantic sea scallop. The Port of New Bedford, Massachusetts is America's #1 Fishing Port with fish landings valued at $369 million. Each year, there are nearly 50 million pounds of sea scallops landed there.[13] The striped bass was driven to low levels early in the 1980s. Catch restrictions were applied in the mid 1980s, and by 1995 this anadromous fish had recovered. The region has valuable mollusk fisheries. Offshore are sea scallops, surfclams, American lobsters and ocean quahog. Inshore are oysters, blue mussels, blue crabs, and clam fisheries. These fisheries are pretty much fully exploited.[5]

The fisheries in the Northeast Region are governed mostly by Fishery Management Plans (FMPs). An example of successful regulation is the 1994 Amendment 4 to the Sea Scallop FMP. This set out to control scallop fishing effort by not accepting more entrants, by restricting the time vessels could fish each day, and by requiring bigger mesh sizes on dredges. Additional protection for scallops was given closing parts of Georges Bank to groundfish fishing. The scallops recovered.[5]

Southeast

The Southeast region spans the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean Sea and the US Southeast Atlantic. Important species are menhaden, drum, croaker, invertebrates, highly migratory species, reef fish and other nearshore species.[5]

Overfishing of king and Spanish mackerel occurred in the 1980s. Regulations were introduced to restrict the size, amount of catch, fishing locations and bag limits for recreational fishers as well as commercial fishers. Gillnets were banned in waters off Florida. By 2001, the mackerel stocks had bounced back.[5]

Menhaden and stone crabs and the three major species of shrimp (pink, brown and white) are fully exploited. Spiny lobster are overexploited. Better data is needed if stocks are to be assessed accurately.[5]

Until 2016, commercial fish farming was prohibited in federal waters, meaning that the Gulf of Mexico was closed to the practice. NOAA announced in January 2016, however, that companies can now set up commercial aquaculture in the Gulf. This is the first opening of federal waters to fish farming, which NOAA hopes will increase production and reduce the US's dependence on foreign fish imports.[14]

Alaska

Alaska provides rich resources. Pacific salmon, shellfish, groundfish, flatfish, Pacific halibut, and herring are underutilized.[5]

The salmon species in Alaska (chinook, coho, pink, sockeye, and chum) generally produce good harvest, though some stocks are declining. Up to 1977, foreign fishing controlled the groundfish fisheries in Alaska (apart from Pacific halibut).[5]

The Aleutian Islands, a series of over 300 rocky islands, stretch over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) from southwest Alaska to Russia. They are home to the largest fishing port in the U.S., Dutch Harbor. The primary target species is pollock, but crabs, salmon and groundfish are also important. Between 1997 and 2001, groundfish were caught by bottom trawling, a fishing method which destroys the habitat of the groundfish, the ocean floor coral and sponge communities. In 2005, about 80,000 km2 (30,000 sq mi) of seafloor around the Aleutian Islands were permanently closed to destructive fishing gears. In 2008, NOAA fisheries created the Aleutian Islands Habitat Conservation Area (AIHCA), most of which is closed to bottom trawling. At 725,000 km2 (280,000 sq mi), the AIHCA is the largest marine protected area in the USA.[15]

Pacific Coast

On the Pacific Coast important species are Pacific halibut, Pacific salmon, groundfish, pelagic fishes and nearshore species. The stocks are mostly overfished or fully exploited.

- Salmon: Salmon production has decreased since the late 1970s, partly due to habitat degradation.

- Groundfish: this harvest is dominated by Pacific whiting. Some stocks need rebuilding. Rockfish can live as long as 100 years, and grow and reproduce very slowly. This makes stock recovery very slow. In 2004, plans for rebuilding several overfished groundfish species were approved .

- Shellfish: Shellfish, such as crabs, clams, shrimp and abalone, sell for high prices, so their fisheries can be small by volume but high by value. These fisheries are mostly fully exploited. Recreational fishers catch more of some species than the commercial fishers.[5]

- Recovering stocks: After decades of decline, Pacific sardine populations are recovering. In 2004, the NMFS declared that, due to reduced harvest and bycatch, Pacific whiting were recovering.[5]

Western Pacific

The Western Pacific region includes the western and central Pacific, the Hawaiian Islands, and the islands of the Northern Marianas, Guam and American Samoa. These are tropical or subtropical waters. They have large species diversity but, because ocean nutrients are not rich, the sustainable yields is low. Pelagic armorhead is the only overfished stock.[5]

- Groundfish fisheries: Groundfish, such as snapper, jacks, emperors and grouper are harvested from coral and rock habitats, mostly around the Hawaiian Islands. While some stocks are underutilized, other important species have declined to 30 percent of their earlier stock levels.[5]

- Invertebrate fisheries: The main invertebrate fisheries are in the north west Hawaiian Islands for slipper and spiny lobster. This fishery started in 1977, peaked in the mid 1980s, and then declined. The decline is thought to stem from oceanographic changes. Some recovery has occurred since 1991, due to entry and harvest restrictions.[5]

- Highly migratory species account for 99 percent catch in this region and are discussed below.

High sea fisheries

The high seas, or international waters, are the waters outside the jurisdiction of the EEZ of any country. U. S. distant fisheries operate in some of these waters, alongside other nations, beyond the jurisdiction of any nation's coastal fisheries.

Highly migratory species

The main commercial species in the high seas are the highly migratory species. These fish make long migrations across the high seas and are fished by many nations. Highly migratory fish also cross boundaries without regard for international laws. In particular, they enter the EEZ zones of the U.S., which means they become important species also for U.S. coastal fisheries.

In the Atlantic, overfished species include:[5]

- Tuna: bigeye in the Atlantic, albacore in the North Atlantic, and bluefin in the West Atlantic, with yellowfin tuna close to being overfished.

- Blue marlin, white marlin and sailfish.

- Sharks: bull, dusky, bignose, night, Caribbean reef, spinner, silky, tiger, lemon, sand, nurse, scalloped, smooth hammerhead and white shark.

The biomass of swordfish in the North Atlantic has increased, probably due to catch reduction and strong recruitment.[5]

In the Pacific, these transboundary fisheries are also important to other Pacific Rim nations and to U.S. fleets fishing within and beyond the EEZ. The major U.S. catch stock is tuna, though billfish, swordfish and shark are also caught. These stocks account for 99 percent of the Western Pacific region's catch.[5]

Seamounts

A seamount is a mountain rising from the ocean seafloor that does not reach the ocean surface. They are defined by oceanographers as independent features that rise at least 1,000 meters above the seafloor. Seamounts became interesting during the 1960s when it was discovered that they can maintain large stocks of commercially important fishes and invertebrates. From 1968 to about 1990, foreign fleets harvested pelagic armorhead across seamounts in the Hawaiian Ridge. Since 1984, fishing been prohibited there so the stock can recover.[5]

Generally, seamounts are found in the high seas, outside the continental shelves and outside the jurisdiction of any nation's EEZ. However, the U.S. Pacific Coast region has an unusually small continental shelf, while the Western Coast region contains islands with no continental shelf. As a result, there are some seamounts within U.S. jurisdiction.

Inland fisheries

Fisheries in inland waters of the United States are small compared to marine fisheries. The largest fisheries are the landings from the Great Lakes, worth about $13 million in 2003,[16] with a similar amount from the Mississippi River basin.[17] This is less than one percent of the dollar value of the marine fisheries.[5]

Fishing fleet

Until the late 19th century, the U.S. fishing fleet used sailing vessels. By the early 20th century, fishing vessels were built as steam boats with steam engines, or as schooners with auxiliary gasoline engines. By the 1930s the fleet was almost completely converted to diesel vessels. Fishing gear became more technical: Alaska purse seiners were in use by 1870, longliners were introduced in 1885; otter trawls were operating in the groundfish and shrimp fisheries by the early 20th century. In the late 1960s, factory ships from other countries started fishing haddock, herring, salmon and halibut on traditional U.S. fishing grounds.[5]

Technological advances have played an important role in the development of U.S. fisheries. Increases in size and speed allowed vessels to fish in more distant waters. Advances include double trawls, the Puretic power blocks for retrieving seine nets, refrigerated holds, durable synthetic fibres for lines and nets, GPS to navigate and locate fishing grounds, fishfinders for the location of fish, and spotter planes to locate fish schools.[5]

The vessel size and gear types of the U.S. fishing fleet varies geographically and between fisheries. Because of this, management of U.S. fisheries with a single policy is not feasible. Individual fisheries have their own biological, economic, and sociological characteristics which make broad policies impractical. On the other hand, ad hoc regulations for individual fisheries is not practical either.[5]

U.S. fisheries use most fishing gear types. Vessels are often configured so they can change rapidly between two or more gear types, such as lobster pots to bottom trawls to scallop dredges. The main techniques are purse seining and trawling. Some vessels freeze their catch at sea, such as factory trawlers, tuna boats, Alaskan crab pot vessels, and some southeast shrimp trawlers. Vessels usually land their catches near their homeports.[5]

Bycatch mitigation

Based in Hawaii is a longline fishery for tuna and billfish. New management approaches, including placing fisheries observers on vessels to observe what is happening with protected species such as albatross and leatherback, loggerhead and green sea turtles, is expected to reduce incidental catch.[18]

Overfished stocks

By 2003, overfishing had occurred on 60 stocks. Another 232 stocks were not overfished. Overfishing had been stopped on 31 stocks, and a gain was made of 13 stocks that had been fully rebuilt. There were 617 other stocks which have limited data or for which criteria for overfishing had not been defined. These stocks mostly have harvests which are not significant, so they are not allocated research funding. Their assessment can be expensive and there is no evidence of overfishing. Rebuilding strategies are operating or are being developed for most stocks which are overfished.

There were 267 major stocks, that is, stocks with at least 200,000 pounds (91,000 kg) in annual landings. Of these, 40 were overfished, 147 were not, and it was not known whether the remaining 80 stocks were overfished. There were 642 minor stocks, of which 20 were overfished, 85 were not, and the remainder had an overfishing status which is unknown or is undefined.[16]

| Status of fisheries[16] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fishery | Region | Not overfished | Overfished |

| Nearshore fisheries | |||

| Coastal fisheries | Northeast | 26 stocks | 18 federally managed stocks are overfished: Gulf of Maine cod, Georges Bank cod, Gulf of Maine haddock, Georges Bank haddock, American Plaice, witch flounder, southern New England/Mid-Atlantic yellowtail flounder, Cape Cod/Gulf of Maine yellowtail flounder, white hake, Southern New England/Mid-Atlantic windowpane flounder, Southern New England winter flounder, ocean pout, Atlantic halibut, barndoor skate, thorny skate, Atlantic salmon, bluefish, golden tilefish, black sea bass, northern monkfish, and southern monkfish. Three of these overfished stocks are not managed under a Federal FMP: American shad, river herring, and Atlantic sturgeon.[5] |

| Coastal fisheries | Southeast | 29 stocks[5] | Overfished species:[5]

|

| Coastal fisheries | Alaska | 2 stocks: the Bering Sea snow crab and the Pribilof Islands blue king crab.[5] | |

| Coastal fisheries | Pacific Coast | The NMFS has listed 26 Pacific Coast salmon stocks as endangered or threatened species under the Endangered Species Act. Salmon recovery will take many years and requires cooperative efforts by federal, state, local, tribal, and private entities. Coastal pelagic fish stocks typically fluctuate widely, and most stocks are low compared to historic levels.[5] | |

| Coastal fisheries | Western Pacific | ||

| Distant fisheries | Atlantic | ||

| Distant fisheries | Pacific | ||

| Inland fisheries | |||

| Overall | 232 stocks[16] | 60 stocks[16] | |

Marine protected areas

A marine protected area (MPA) is federally defined as: “any area of the marine environment that has been reserved by federal, state, tribal, territorial, or local laws or regulations to provide lasting protection for part or all of the natural and cultural resources therein.”[19]

Fourteen MPAs covering 150,000 square miles (390,000 km2) have been federally designated as National Marine Sanctuaries, and are administered by a division of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).[2]

In practice, these MPAs are defined areas where natural and/or cultural resources are given more protection than occurs in the surrounding waters. United States MPAs cover many habitats including the open ocean, coastal areas, intertidal zones, estuaries, and the Great Lakes. They vary in purpose, legal authorities, agencies, management approaches, level of protection, and restrictions on human uses.[20]

Aquaculture

The value of aquaculture products grew from $45 million in 1974 to about $866 million (393,400 tonnes) in 2003.[16]

Aquaculture, in the United States, includes the farming of hatchery fish and shellfish which are grown to market size in ponds, tanks, cages, or raceways and released into the wild. Aquaculture is also used to support commercial and recreational marine fisheries by enhancing or rebuilding wild stock populations. It also includes the cultivation of ornamental fish for the aquarium trade, as well as plant species used in various pharmaceutical, nutritional, and biotechnology products.[21]

According to the FAO, in 2004 the United States ranked 10th in total aquaculture production, behind China, India, Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Japan, Chile, and Norway. The United States imports aquaculture products from these and other countries, and operates an annual seafood trade deficit of over $9 billion.[21]

Shellfish (oysters, clams, mussels), account for two-thirds of marine aquaculture production, followed by salmon (25 percent) and shrimp (10 percent). Production occurs mainly on land, in ponds, and in coastal waters under state jurisdiction. As a result of recent advances in offshore aquaculture technology, commercial finfish and shellfish operations have been established in more exposed, open ocean locations in state waters in New Hampshire, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico.[21]

Total U.S. aquaculture production, including aquatic plants, is about $1 billion annually, compared to the total world production of about $70 billion. Only about 20 percent of U.S. aquaculture production is from marine species. NOAA estimates that the annual U.S. domestic aquaculture production of all species could increase from about 0.5 million tons to 1.5 million tons by 2025.[21]

Subsidies

In a study of federal investment in the fishery sector, most aspects of United States tax, fisheries, and societal policies were examined to see whether they created subsidies for the fishing industry and whether these subsidies had impacts. The gross value of direct U.S. subsidies was about 0.5% of the gross ex-vessel value of commercial landings. There are no major ship construction subsidies, market development or other forms of assistance that often exist in developed and developing fishing industries around the world.[22]

Recreational

In 2006, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimated that 30.0 million U.S. anglers, 16 years old and older took 403 million fishing trips, spending $42.0 billion in fishing related expenses. Of these, 25.4 million were freshwater anglers who took 337 million trips and spent $26.3 billion. Saltwater fishing attracted 7.7 million anglers who took 67 million trips and spent $8.9 billion.[23]

| Recreational fishing expenditures in $US billion[23] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| subtotal | total | percent | |

| Food and lodging | 6.3 | ||

| Transportation | 5.0 | ||

| Other trip costs: land use fees, guide fees, equipment rental, boating expenses, and bait… |

6.6 | ||

| Trip-related, total | 17.9 | ||

| Fishing equipment: rods, reels, tackle boxes, depth finders, and artificial lures and flies… |

5.3 | ||

| Auxiliary equipment: camping equipment, binoculars, and special fishing clothing… |

0.8 | ||

| Special equipment: boats, vans, and cabins… | 13.2 | ||

| Equipment, total | 18.8 | ||

| Magazines, books | 0.1 | ||

| Membership dues and contributions | 0.2 | ||

| Land leasing and ownership | 4.6 | ||

| Licenses, stamps, tags, and permits | 0.5 | ||

| Other, total | 5.4 | ||

| Overall total | 42.0 | 100 | |

See also

- Magnuson-Stevens Fisheries Conservation and Management Act of 1976

- Tidelands

- Continental shelf of the United States

References

- 1 2 CIA: Factbook:USA

- 1 2 NOAA: Frequently Asked Questions National Marine Sanctuaries

- ↑ Harvey DJ (2004) Aquaculture Outlook Electronic Outlook Report from the Economic Research Service.

- ↑ U S Department Of Commerce Aquaculture Policy

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 FAO Profile for the USA

- ↑

- ↑ FAO Profile for the USA, Page 3.

- ↑ FAO: Fisheries and Aquaculture 2005 statistics.

- ↑ NOAA Fisheries: Office of Sustainable Fisheries

- ↑ NOAA Fisheries 2001 Report NOAA/NMFS, Silver Spring, MD USA.

- ↑ NOAA: Fishwatch: Trade

- ↑ excludes exports, is live weight, and includes military abroad

- ↑ http://www.portofnewbedford.org/commercial-fishing/our-commercial-fishing-industry

- ↑ Wendland, Tegan. "Gulf Of Mexico Open For Fish-Farming Business". NPR.org. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

- ↑ Marine Conservation Biology Institute: Aleutian Islands Retrieved 20 January 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 NOAA/NMFS: (2004) Fisheries of the United States, 2003

- ↑ Mac, MJ, Opler PA, Haecker P, and Doran PD (1998) Status and trends of nation's biological resources 2 vols. U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Va.

- ↑ Mitigation measures Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council

- ↑ Executive Order 13158 (May 2000)

- ↑ The basics National Marine Protected Areas Center.

- 1 2 3 4 Aquaculture in the United States Archived 24 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. NOAA Aquaculture Program. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ↑ Federal Fisheries Investment Task Force Report to Congress, July 1999.

- 1 2 [library.fws.gov/nat_survey2006_final.pdf 2006 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation] U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

.svg.png)