United States passport

| United States passport | |

|---|---|

The front cover of a contemporary United States biometric passport. | |

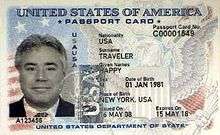

Front of a United States Passport Card (2009). | |

| Date first issued |

December 30, 2005 (diplomatic biometric passport booklet) 2006 (regular biometric passport booklet)[1] |

| Issued by |

|

| Type of document | Passport |

| Purpose | Identification |

| Eligibility requirements | United States nationality |

| Expiration | normally 10 years after acquisition for people at least age 16; 5 years for minors under 16[2] |

| Cost |

Booklet: $135 (first)/$110 (renewal)/$105 (minors) Card: $55 (first)/$30 (when applying for or holder of a valid passport booklet)/$40 (minor)/$15 (minor, when applying for passport booklet)[3] |

United States passports are passports issued to citizens and non-citizen nationals of the United States of America.[4] They are issued exclusively by the U.S. Department of State.[5] Besides passports (in booklet form), limited use passport cards are issued by the same organization subject to the same requirements.[6] It is unlawful for U.S. citizens to enter or exit the United States without a valid U.S. passport or Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative-compliant passport-replacement document, or without an exception or waiver.[7][8][9]

U.S. passport booklets are valid for travel by Americans to certain countries and/or for certain purposes though it may require a visa and the U.S. itself restricts its nationals from traveling to or engaging in commercial transactions in certain countries. They conform with recommended standards (i.e., size, composition, layout, technology) of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO).[10] There are five types of passport booklets; as well, the Department of State has issued only biometric passports as standard since August 2007, though non-biometric passports are valid until their expiry dates.[11] United States passports are property of the United States and must be returned to the US Government upon demand.[12]

By law, a valid unexpired U.S. passport (or passport card) is conclusive (and not just prima facie) proof of U.S. citizenship, and has the same force and effect as proof of United States citizenship as certificates of naturalization or of citizenship, if issued to a U.S. citizen for the full period allowed by law.[13] U.S. law does not prohibit U.S. citizens from holding passports of other countries, though they are required to use their U.S. passport to enter and leave the U.S.[14]

History

American consular officials issued passports to some citizens of some of the thirteen states during the War for Independence (1775–1783). Passports were sheets of paper printed on one side, included a description of the bearer, and were valid for three to six months. The minister to France, Benjamin Franklin, based the design of passports issued by his mission on that of the French passport.[15]

From 1776 to 1783, no state government had a passport requirement. The Articles of Confederation government (1783–1789) did not have a passport requirement

The Department of Foreign Affairs of the war period also issued passports, and the department, carried over by the Articles of Confederation government (1783–1789), continued to issue passports. In July 1789, the Department of Foreign Affairs was carried over by the government established under the Constitution. In September of that year, the name of the department was changed to Department of State. The department handled foreign relations and issued passports, and, until the mid-19th century had various domestic duties.

For decades thereafter, passports were issued not only by the Department of State but also by states and cities, and by notaries public. For example, an internal passport dated 1815 was presented to Massachusetts citizen George Barker to allow him to travel as a free black man to visit relatives in Southern slave states.[16] Passports issued by American authorities other than the Department of State breached propriety and caused confusion abroad. Some European countries refused to recognize passports not issued by the Department of State, unless United States consular officials endorsed them. The problems led the Congress in 1856 to give to the Department of State the sole authority to issue passports.[17][18]

From 1789 through late 1941, the constitutionally established government, required passports of citizens only during two periods: during the American Civil War (1861–1865), as well as during and shortly after World War I (1914–1918). The passport requirement of the Civil War era lacked statutory authority. During World War I (1914–1918), European countries instituted passport requirements. The Travel Control Act of May 22, 1918, permitted the president, when the United States was at war, to proclaim a passport requirement, and President Wilson issued such a proclamation on August 18, 1918. World War I ended on November 11, 1918, but the passport requirement lingered until March 3, 1921, the last day of the Wilson administration.[19]

In Europe, general peace between the end of the Napoleonic Wars (1815) and the beginning of World War I (1914), and development of rail roads, gave rise to international travel by large numbers of people. Countries such as Czarist Russia and the Ottoman Empire maintained passport requirements. After World War I, many European countries retained their passport requirements. Foreign passport requirements undercut the absence of a passport requirement for Americans, under United States law, between 1921 and 1941.

There was an absence of a passport requirement under United States law between 1921 and 1941. World War II (1939–1945) again led to passport requirements under the Travel Control Act of 1918.

The contemporary period of required passports for Americans under United States law began on November 29, 1941.[20] A 1978 amendment to the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 made it unlawful to enter or depart the United States without an issued passport even in peacetime.[21]

Even when passports were not usually required, Americans requested U.S. passports. Records of the Department of State show that 130,360 passports were issued between 1810 and 1873, and that 369,844 passports were issued between 1877 and 1909. Some of those passports were family passports or group passports. A passport application could cover, variously, a wife, a child, or children, one or more servants, or a woman traveling under the protection of a man. The passport would be issued to the man. Similarly, a passport application could cover a child traveling with his or her mother. The passport would be issued to the mother. The number of Americans who traveled without passports is unknown.[22]

The League of Nations held a conference in 1920 concerning passports and through-train travel, and conferences in 1926 and 1927 concerning passports. The 1920 conference put forward guidelines on the layout and features of passports, which the 1926 and 1927 conferences followed up. Those guidelines were steps in the shaping of contemporary passports. One of the guidelines was about 32-page passport booklets, such as the U.S. type III mentioned in this section, below. Another guideline was about languages in passports. See Languages, below. A conference on travel and tourism held by the United Nations in 1963 did not result in standardised passports. Passport standardization was accomplished in 1980 under the auspices of the International Civil Aviation Organization.

The design and contents of U.S. passports changed over the years.[23] Prior to World War I the passport was typically a large (11 x 17 inch) diploma, with a large engraved seal of the Department of State at the top, repeated in red wax at the bottom, the bearer's description and signature on the left, and his name on the right above space for data such as "accompanied by his wife," all in ornate script. In 1926, the Department of State introduced the type III passport. This had a stiff red cover, with a window cutout through which the passport number was visible. That style of passport contained 32 pages.[24] American passports had green covers from 1941 until 1976, when the cover was changed to blue, as part of the U.S. bicentennial celebration. Green covers were again issued from April 1993, until March 1994, and included a special one-page tribute to Benjamin Franklin in commemoration of the 200th anniversary of the United States Consular Service. Currently blue passports, with the pages showing historical and natural scenes of the U.S., are issued. Initially a U.S. passport was issued for two years, although by the 1950s on application by the holder a passport could be stamped so that this time was extended without reissue. In the succeeding decades the initial lengths for adult applicants were extended to three, five, and eventually to ten years, the current standard. At this time stamping for a further extension is not allowed.

In 1981, the United States became the first country to introduce machine-readable passports.[25] In 2000, the Department of State started to issue passports with digital photos, and as of 2010, all previous series have expired. In 2006, the Department of State began to issue biometric passports to diplomats and other officials.[26] Later in 2006, biometric passports were issued to the public.[1] Since August 2007, the department has issued only biometric passports, which include RFID chips. An issued non-biometric will remain valid until its stated date of expiration.[27]

At some time during 2017, the United States Department of State is expected to issue a next generation of the US biometric passport. The passport will have an embedded data chip on the information page protected by a polycarbonate coating; this will help prevent the book from getting wet and bending, and—should your passport be stolen—the chip will keep people from stealing your personal information and falsifying an identity. The passport number will also be laser cut as tapered, perforated holes through pages—just one of several components of the "Next Generation" passport, including artwork upgrade, new security features such as a watermark, "tactile features," and more "optically variable" inks. In other words: Some designs on pages will be raised, and ink—depending on the viewing angle—will appear to be different colors.[28]

Administration

Authority for issuing passports is conferred on the Secretary of State by the Passport Act of 1926,[29] subject to such rules as the President of the United States may prescribe.[30] The Department of State has issued regulations governing such passports,[31] and its internal policy concerning issuance of passports, passport waivers, and travel letters is contained in the Foreign Affairs Manual. [32]

The responsibility for passport issuance lies with Passport Services, which is within the Department of State, and a unit of the Bureau of Consular Affairs. They operate twenty-two regional passport agencies in the United States to serve the general public.[33] The most recent additions include the opening of public counters at the National Passport Center in New Hampshire and at the Arkansas Agency, as well as opening New York's second regional agency in Buffalo in October 2010.[34] Additionally, Passport Services opened regional agencies in Atlanta, El Paso, Texas, and San Diego in 2011.[35] Passport applications at most of these locations require that citizens provide proof of travel within 14 days of the application date, or who need to obtain foreign visas before traveling.

There are about 9,000 passport acceptance facilities in the United States, designated by Passport Services, at which routine passport applications may be filed. These facilities include United States courts, state courts, post offices, public libraries, county offices, and city offices.[36] In fiscal year 2015, the Department of State issued 15,556,216 (includes 1,647,413 passport cards) and there were 125,907,176 valid U.S. passports in circulation.[37] The passport possession rate of the U.S. was approximately 39% of the population in 2015.

It is unlawful to enter or exit the United States without a valid passport or Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative-compliant passport-replacement document, or without an exception or waiver.[7][8][9]

The use of passports may be restricted for foreign policy reasons. In September 1939, in order to preserve the United States' neutrality in relation to the breakout of World War II, then Secretary of State Cordell Hull issued regulations declaring that outstanding passports, together with passports issued thereafter, could not be used for travel to Europe without specific validation by the Department of State, and such validation could not last more than six months.[38] Similar restrictions can still be invoked upon notice given in the Federal Register.[39]

As confirmed in Haig v. Agee, the administration may deny or revoke passports for foreign policy or national security reasons at any time,[7] as well as for other reasons as prescribed by regulations.[40] A notable example of enforcement of this was the 1948 denial of a passport to U.S. Representative Leo Isacson, who sought to go to Paris to attend a conference as an observer for the American Council for a Democratic Greece, a Communist front organization, because of the group's role in opposing the Greek government in the Greek Civil War.[41][42] Denial or revocation of a passport does not prevent the use of outstanding valid passports.[43] The physical revocation of a passport is often difficult, and an apparently valid passport can be used for travel until officially taken by an arresting officer or by a court.[43]

It should be noted that the lack of a valid passport (for whatever reason, including revocation) does not render the U.S. citizen either unable to leave the United States, or inadmissible into the United States. The United States is a signatory of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which guarantees residents of its signatories wide-ranging rights to enter or depart their own countries. In Nguyen v. INS, the Supreme Court stated that U.S. citizens are entitled "...to the absolute right to enter its borders."[44] Lower federal courts went as far as to declare that "...the Government cannot say to its citizen, standing beyond its border, that his reentry into the land of his allegiance is a criminal offense; and this we conclude is a sound principle whether or not the citizen has a passport, and however wrongful may have been his conduct in effecting his departure."[45] Therefore, U.S. border control facilities don't deny U.S. citizens entry even in the absence of a valid passport, though these travellers may be delayed while the CBP attempts to verify their identity and citizenship status.[46] The U.S. does not exercise passport control on exit from the country,[47] so the individual attempting to depart from the U.S. only needs to have valid documents granting him/her right to entry into the country of destination.

Visa requirements

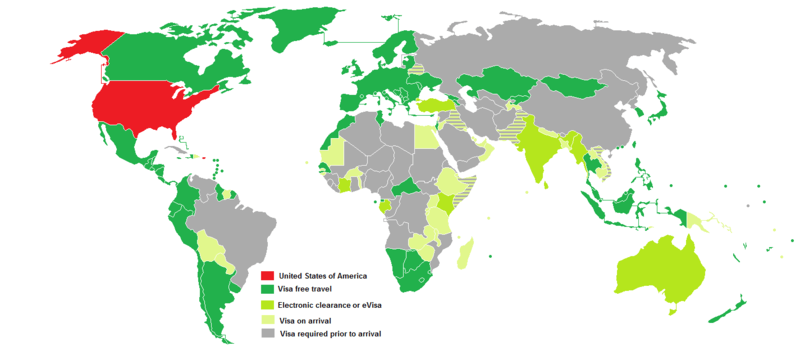

Countries and territories with visa-free or visa-on-arrival entries for holders of regular United States passports

Visa requirements for the United States citizens are administrative entry restrictions by the authorities of other states placed on citizens of United States. According to the 2016 Visa Restrictions Index, holders of a United States passport can visit 174 countries and territories visa-free or with visa on arrival.[48] The United States passport is currently ranked 4th alongside with Luxembourg, Austria, Portugal and Singapore, who all have a score of 154 in terms of travel freedom in the world as ranked by Arton Capital [49][50][51][52]

Foreign travel statistics

These are the numbers of visits by US nationals to various countries in 2014 (unless otherwise noted):

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 Data for 2015

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Counting only guests in tourist accommodation establishments.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Data for 2013

- 1 2 3 4 Data for arrivals by air only.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Data for 2010

- ↑ Data for 2007

- 1 2 Data for 2011

- 1 2 3 Data for 2009

- ↑ Data for 2005

- ↑ Data for arrivals by air only.

Passport requirements

Citizens and non-citizen nationals

United States passports are issuable only to persons who owe permanent allegiance to the United States – i.e., citizens and non-citizen nationals of the United States.[188]

"All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States ..."[189] Under this provision, "United States" means the 50 states and the District of Columbia only.[190]

By acts of Congress, every person born in Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands is a United States citizen by birth.[191] Also, every person born in the former Panama Canal Zone whose father or mother (or both) was a citizen is a United States citizen by birth.[192]

Other acts of Congress provide for acquisition of citizenship by persons born abroad.[193]

Every citizen is a national of the United States, but not every national is a citizen. There is a small class of American Samoans, born in American Samoa, including Swains Island, who are nationals but not citizens of the United States,[194] This is because people born in American Samoa are not automatically granted US citizenship by birth.[195] See Passport message, below.

United States law permits dual nationality.[196] Consequently, it is permissible to have and use a foreign passport. However, U.S. citizens are required to use a U.S. passport when leaving or entering the United States.[197] This requirement extends to a U.S. citizen who is a dual national.[198]

Separate passports are issued to U.S. citizens on official business, and to diplomats, a process followed by all countries. The United Nations laissez-passer is a similar document issued by that international organization.

Passport in lieu of certificate of non-citizenship nationality

Few requests for certificates of non-citizenship nationality are made to the Department of State, which are issuable by the department. Production of a limited number of certificates would be costly, which if produced certificates would have to meet stringent security standards. Due to this, the Department of State chooses not to issue certificates of non-citizen nationality. As an alternative, they choose to issues passports to non-citizen nationals. The issued passport certifies the status of a non-citizen national.[199] The certification is in the form of an endorsement in the passport: "The bearer of this passport is a United States national and not a United States citizen."

Application

An application is required for the issuance of a passport.[200] If a fugitive being extradited to the United States refuses to sign a passport application, the consular officer can sign it "without recourse."[201]

An application for a United States passport made abroad is forwarded by a U.S. embassy or consulate to Passport Services for processing in the United States. The resulting passport is sent to the embassy or consulate for issuance to the applicant. An emergency passport is issuable by the embassy or consulate. Regular issuance takes approximately 4–6 weeks.[202] As per Haig v. Agee, the Presidential administration may deny or revoke passports for foreign policy or national security reasons at any time.

Places where a U.S. passport may be applied for include post offices and libraries.[203]

Forms

DS11 Standard[204]

- The applicant has never been issued a U.S. passport

- The applicant is under age 16

- The applicant was under age 16 when upon the issuance of the applicants previous passport

- The applicant's recent U.S. passport was issued more than 15 years ago

- The applicant's most recent U.S. passport was lost or stolen

- The applicant's name has changed since the applicant's U.S. passport was issued and the applicant is unable to legally document the change of name

A traveller needs to go in person, and pay an extra $25.

DS82 Renewal[205]

The applicant's most recent U.S. passport:

- Is undamaged and can be submitted with your application

- Was issued when the applicant was age 16 or older

- Was issued within the last 15 years

- Was issued in the applicant's current name or the applicant can legally document a change of name

The advantage of the renewal form is a traveller can mail in the form, and avoid paying an extra $25. Also, the DS82 can only be used by those who reside in the USA or Canada. Anyone else outside the country must reapply using the DS11 form.[206]

DS64 Lost[207]

Lost or stolen passport requires DS64 in addition to DS11 only if the lost passport is valid due to the second passport rule:

Second passport

More than one valid United States passport of the same type may not be held, except if authorized by the Department of State.[208]

It is routine for the Department of State to authorize a holder of a regular passport to hold, in addition, a diplomatic passport or an official passport or a no-fee passport.

One circumstance which may call for issuance of a second passport of a particular type is a prolonged visa-processing delay. Another is safety or security, such as travel between Israel and a country which refuses to grant entry to a person with a passport which indicates travel to Israel. The period of validity of a second passport issued under either circumstance is generally two years from the date of issue.[209]

Those who need a second identification document in addition to the U.S. passport may hold a U.S. passport card. This passport card is used by U.S. citizens living abroad when they need to renew their regular passport book, renew their residency permit or apply for a visa - in other words, when they cannot show their regular passport yet are required by local law to carry valid identification.

Document requirements

- in-state valid photo ID

- birth certificate or naturalization certificate

- 2x2 photo

Passport photograph

Passport photo requirements are very specific.[210][211][212] Official U.S. state department photographic guidelines are available online.[213]

- 2 in × 2 in (5.1 cm × 5.1 cm)

- The height of the head (top of hair to bottom of chin) should measure 1 to 1 3⁄8 inches (25 to 35 mm)

- Eye height is between 1 1⁄8 to 1 3⁄8 inches (29 to 35 mm) from the bottom of the photo

- Front view, full face, open eyes, closed mouth, and neutral expression

- Full head from top of hair to shoulders

- Plain white or off-white background

- No shadows on face or in background

- No sunglasses (unless medically necessary). As of Nov. 1, 2016, the wear of eyeglasses in U.S. passport photos is not allowed.

- No hat or head covering (unless for religious purposes; religious head covering must not obscure hairline)

- Normal contrast and lighting

Fees

Fees for applying vary based on whether or not an applicant is applying for a new passport or they are renewing an expiring passport. Fees also vary depending on whether an applicant is under the age of 16.

First time applications

First time adult applicants are charged $110 per passport book and $30 per passport card. Additionally, a $25 execution fee is charged per transaction, but only for first applications and not for renewals. This means that if a person were to apply for the passport book and card simultaneously on the same application, they would pay only one execution fee.[214]

All minor applicants are considered first-time applicants until they reach age 16. Minor applicants pay an $80 application fee for the passport book and a $15 application fee for the passport card. The same $25 execution fee is charged per application.[214]

Renewal applications

Adults wishing to renew their passports may do so up to five years after expiration at a cost of $110 for the passport book and $30 for the passport card. Passports for minors under age 16 cannot be renewed.[214]

Special renewal rules

If a person is already in possession of a passport book and would like a passport card additionally (or vice versa), they may submit their currently valid passport book or card as evidence of citizenship and apply for a renewal to avoid paying the $25 execution fee. However, if the passport book or card holder is unable or unwilling to relinquish their currently valid passport for the duration of the processing, they may submit other primary evidence of citizenship, such as a U.S. birth certificate or naturalization certificate, and apply as a first time applicant, paying the execution fee and submitting a written explanation as to why they are applying in this manner.[215]

Additional Fees

- An expedite fee of $60 is charged when applicants request faster processing, regardless of age. This processing is currently 2–3 weeks when applying at an acceptance facility. The same fee is charged for expedited service when applying at a Passport Agency within 14 days of travel.[216]

- In addition to the expedite fee, applicants may pay an additional $20.66 to receive overnight mail return when their application has finished processing.[217] This can be paid in combination with the application fee when applying, or added later by calling the National Passport Information Center. However, overnight mail return is only available for the U.S. Passport Book. Passport cards may not be overnight mailed.[217]

- As of January 1, 2016, passports may no longer have pages added to them. When applying for a new passport, applicants may apply for a 28-page or 52-page passport, with no additional cost for obtaining the 52-page passport.[218][219]

Types of passports

- Regular (dark blue cover)

- Issuable to all citizens and non-citizen nationals. Periods of validity: for those age 16 or over, generally ten years from the date of issue; for those 15 and younger, generally five years from the date of issue.[220][221] A sub-type of regular passports is no-fee passports, issuable to citizens in specified categories for specified purposes. For example; an American sailor, for travel connected with his duties aboard a U.S.-flag vessel. Period of validity: generally 10 years from the date of issue.[222] A no-fee passport has an endorsement which prohibits its use for a purpose other than the specified purpose.

- Official (reddish brown cover)

- Issuable to citizen-employees of the United States assigned overseas, either permanently or temporarily, and their eligible dependents, and to some members of Congress who travel abroad on official business. Also issued to U.S. military personnel when deployed overseas. Period of validity: generally five years from the date of issue.[223]

- Diplomatic (black cover)

- Issuable to American diplomats accredited overseas and their eligible dependents, to citizens who reside in the United States and travel abroad for diplomatic work, to the President of the United States, the President-Elect, the Vice President and Vice President-elect and former presidents and vice presidents. Supreme Court Justices, current cabinet members, former secretaries and deputy secretaries of state, the Attorney General and Deputy Attorney General, some members of Congress and retired career ambassadors are also eligible for a diplomatic passport.[224] Period of validity: generally five years from the date of issue.[225]

- Refugee Travel Document (also known as "Refugee Passport") (blue-green cover)

- Not a full passport, but issued to aliens who have been classified as refugees or asylees.[226]

- Re-entry Permit (blue-green cover), cover titled "Travel Document"

- Not a full passport, but issued to a permanent resident alien in lieu of a passport. The reentry permit guarantees them permission to reenter the U.S. and is usually valid for a period of two years.[227][228] A reentry permit can also be used by permanent residents who are stateless or cannot get a passport for international travel, or who wish to visit a country they cannot on their passport.[229]

- Emergency

- Issuable to citizens overseas, in urgent circumstances. Period of validity: generally one year from the date of issue.[230] An emergency passport may be exchanged for a full-term passport.[231]

- U.S. passport card

- Not a full passport, but a small ID card issued by the U.S. government for crossing land and sea borders with Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean and Bermuda. The passport card is not valid for International air travel.[6] It is possible to hold the U.S. passport card in addition to a regular passport.[232]

Passport layout

Format

On the front cover, a representation of the Coat of arms of the United States is at the center. "PASSPORT" (in all capital letters) appears above the representation of the Great Seal, and "United States of America" (in Garamond italic) appears below.

An Official passport has "OFFICIAL" (in all capital letters) above "PASSPORT". The capital letters of "OFFICIAL" are somewhat smaller than the capital letters of "PASSPORT".

A Diplomatic passport has "DIPLOMATIC" (in all capital letters) above "PASSPORT". The capital letters of "DIPLOMATIC" are somewhat smaller than the capital letters of "PASSPORT".

A Travel Document, in both forms (Refugee Travel Document and Permit to Re-Enter), features the seal of the Department of Homeland Security instead of the Great Seal of the United States. Above the seal the words "TRAVEL DOCUMENT" appears in all capital letters. Below the seal is the legend "Issued by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services" in upper and lower case.

In 2007, the passport was redesigned, after previous redesign in 1993. There are 13 quotes in the 28-page version of the passport and patriotic-themed images on the background of the pages.[233]

A biometric passport has the e-passport symbol at the bottom.

There are 32 pages in a biometric passport. Frequent travelers may request 52-page passports for no additional cost. Extra visa pages may be added to a passport.[234] Extra visa pages can be added by mail (if the passport holder resides in the U.S.) and at most U.S. embassies and consulates (if the passport holder resides or visits a country overseas). The addition of visa pages used to be free, but as of July 13, 2010, the service costs $82. As of January 1, 2016, the service is discontinued entirely, for security reasons.[219]

Data page and signature page

Each passport has a data page and a signature page.

A data page has a visual zone and a machine-readable zone. The visual zone has a digitized photograph of the passport holder, data about the passport, and data about the passport holder:

- Photograph

- Type [of document, which is "P" for "passport"]

- Code [of the issuing country, which is "USA" for "United States of America"]

- Passport No.

- Surname

- Given Name(s)

- Nationality

- Date of Birth

- Place of Birth (lists the state/territory followed by "U.S.A." for those born in the United States; lists the current name of the country of birth for those born abroad)

- Sex

- Date of Issue

- Date of Expiration

- Authority

- Endorsements

The machine-readable zone is present at the bottom of the page and contains P<USA[SURNAME]<<[GIVEN NAME(S)]<<<<<<<<<< in the first line and [PASSPORT NO. + 1 DIGIT]USA[DATE OF BIRTH + 1 DIGIT + SEX + DATE OF EXPIRATION + 10 DIGITS]<[6 DIGITS] in the second line. Both lines contain 44 characters in a fixed-width all-caps font, with the top line ending with enough left angle brackets to fill the 44 character limit.

A signature page has a line for the signature of a passport holder. A passport is not valid until it is signed by the passport holder. If a holder is unable to sign his passport, it is to be signed by a person who has legal authority to sign on the holder's behalf.[235]

Place of birth

Place of birth was first added to U.S. passports in 1917. The standards for the names of places of birth that appear in passports are listed in volume 7 of the Foreign Affairs Manual, published by the Department of State.[236][237] A request to list no place of birth in a passport is never accepted.[238]

For birthplaces within the United States and its territories, it contains the name of the state or territory followed by "U.S.A.", except for the U.S. Virgin Islands and American Samoa. For persons born in the District of Columbia, passports indicate "Washington, D.C., U.S.A." as the place of birth. For persons born in the U.S. Virgin Islands or American Samoa, passport indicate "U.S. Virgin Islands" or "American Samoa" without "U.S.A.".

For places of birth located outside the United States, only the country or dependent territory is mentioned. The name of the country is the current name of the country that is presently in control of the territory the place of birth and thus changes upon a change of a country name. For example, people born before 1991 in the former Soviet Union (including the Baltic states, whose annexation by the Soviet Union was never recognized by the U.S.) would have the post-Soviet country name listed as the place of birth. Another example is for birth in the former Panama Canal Zone, "Panama" is listed as the place of birth. A citizen born outside the United States may be able to have his city or town of birth entered in his passport, if he or she objects to the standard country name. However, if a foreign country denies a visa or entry due to the place-of-birth designation, the Department of State will issue a replacement passport at normal fees, and will not facilitate entry into the foreign country.[239]

Provisions exists to deal with the complexities of the Greater China Region. As per the One-China policy, the United States recognizes the People's Republic of China as the sole legal government of China, and acknowledges the Chinese position that Taiwan is a part of China. However, people born in Taiwan can choose to have either "Taiwan", "China" or their city of birth listed as place of birth. People born in Hong Kong or Macau would have their place of birth as "Hong Kong SAR" or "Macau SAR," but the option of listing the city of birth only (e.g. "Hong Kong" without "SAR") is not available. As Tibet is recognized as an integral part of China, the place of birth for people born in Tibet is written as "China", with the option of listing only the city of birth.[240]

Special provisions are in place for people born in Israel and Israeli-occupied territories. For birth in places other than Jerusalem (using its 1948 municipal borders) and the Golan Heights, "Israel", "West Bank" or "Gaza Strip" is used. If born before 1948, "Palestine" may be used. For birth in the Golan Heights, "Syria" is used regardless of date of birth. Due to the legal uncertainty of the status of Jerusalem, for birth in Jerusalem within its 1948 municipal borders, "Jerusalem" is used regardless of date of birth.[241] In 2002, Congress passed legislation that said that American citizens born in Jerusalem may list "Israel" as their country of birth, although Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama have not allowed it.[242] A federal appeals court declared the 2002 law invalid on July 23, 2013,[243] and the Supreme Court upheld that decision on June 8, 2015.[244] In all cases, the city or town of birth may be used in place of the standard designations.[241]

For birth aboard aircraft and ships, if the birth occurs in an area where no country has sovereignty (i.e. over international waters), the place of birth is listed as "in the air" or "at sea" where appropriate.[245]

Passport message

Passports of many countries contain a message, nominally from the official who is in charge of passport issuance (e.g., secretary of state, minister of foreign affairs), addressed to authorities of other countries. The message identifies the bearer as a citizen of the issuing country, requests that he or she be allowed to enter and pass through the other country, and requests further that, when necessary, he or she be given help consistent with international norms. In American passports, the message is in English, French, and Spanish. The message reads:

In English:

- The Secretary of State of the United States of America hereby requests all whom it may concern to permit the citizen/national of the United States named herein to pass without delay or hindrance and in case of need to give all lawful aid and protection.

in French:

- Le Secrétaire d'État des États-Unis d'Amérique prie par les présentes toutes autorités compétentes de laisser passer le citoyen ou ressortissant des États-Unis titulaire du présent passeport, sans délai ni difficulté et, en cas de besoin, de lui accorder toute aide et protection légitimes.

and in Spanish:

- El Secretario de Estado de los Estados Unidos de América por el presente solicita a las autoridades competentes permitir el paso del ciudadano o nacional de los Estados Unidos aquí nombrado, sin demora ni dificultades, y en caso de necesidad, prestarle toda la ayuda y protección lícitas.

The term "citizen/national" and its equivalent terms ("citoyen ou ressortissant"; "ciudadano o nacional") are used in the message as some people born in American Samoa, including Swains Island, are nationals but not citizens of the United States.

The masculine inflections of "Le Secrétaire d'État" and "El Secretario de Estado" are used in all passports, regardless of the sex of the Secretary of State at the time of issue.

Languages

At a League of Nations conference in 1920 about passports and through-train travel, a recommendation was that passports be written in French (historically, the language of diplomacy) and one other language.

English, the de facto national language of the United States, has always been used in U.S. passports. At some point subsequent to 1920, English and French were used in passports. Spanish was added during the second Clinton administration, in recognition of Spanish-speaking Puerto Rico.

The field names on the data page, the passport message, the warning on the second page that the bearer is responsible for obtaining visas, and the designations of the amendments-and-endorsements pages, are printed in English, French, and Spanish.

Biometric passport

The legal driving force of biometric passports is the Enhanced Border Security and Visa Entry Reform Act of 2002, which states that smart-card Identity cards may be used in lieu of visas. That law also provides that foreigners who travel to the U.S., and want to enter the U.S. visa-free under the Visa Waiver Program, must bear machine-readable passports that comply with international standards. If a foreign passport was issued on or after October 26, 2006, that passport must be a biometric passport.

The electronic chip in the back cover of a U.S. passport stores an image of the photograph of the passport holder, passport data, and personal data of the passport holder; and has capacity to store additional data.[27] The capacity of the Radio-frequency identification (RFID) chip is 64 kilobytes, which is large enough to store additional biometric identifiers in the future, such as fingerprints and iris scans.

Data in a passport chip is scannable by electronic readers, a capability which is intended to speed up immigration processing. A passport does not have to be plugged into a reader in order for the data to be read. Like toll-road chips, data in passport chips can be read when passport chips are proximate to readers. The passport cover contains a radio-frequency shield, so the cover must be opened for the data to be read.

According to the Department of State, the Basic Access Control (BAC) security protocol prevents access to that data unless the printed information within the passport is also known or can be guessed.[246]

According to privacy advocates, the BAC and the shielded cover are ineffective when a passport is open, and a passport may have to be opened for inspection in a public place such as a hotel, a bank, or an Internet cafe. An open passport is subject to unwelcome reading of chip data, such as by a government agent who is tracking a passport holder's movements or by a criminal who is intending identity theft.[247]

Gallery of historic images

Cover of a non-biometric passport issued prior to August 2007.

Cover of a non-biometric passport issued prior to August 2007.- Cover of a passport (1976).

Cover of a passport (1930).

Cover of a passport (1930).

See also

- Iroquois passport

- Passport

- People who lost United States citizenship

- Ruth Shipley, head of the Passport Division, 1928 to 1955

- Visa policy of the United States

- Visa requirements for United States citizens

References

- 1 2 "Department of State Begins Issuance of an Electronic Passport". U.S. Department of State, Office of the Spokesman. U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on December 31, 2006. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions". U.S. Passports & International Travel. United States Department of State. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ↑ "U.S. Passports & International Travel".

- ↑ 22 U.S.C. sec. 212; Passports.

- ↑ 22 U.S.C. sec. 211a; Passports

- 1 2 "Passport Card". U.S. Department of State.

- 1 2 3 Capassakis, Evelyn (1981). "Passport Revocations or Denials on the Ground of National Security and Foreign Policy". Fordham L. Rev. 49 (6): 1178–1196.

- 1 2 § 215 of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (currently codified at 8 U.S.C. § 1185)

- 1 2 22 C.F.R. 53

- ↑ International Civil Aviation Organization, Doc 9303, Machine Readable Travel Documents, Part 1: Machine Readable Passport, Volume 1, Passports with Machine Readable Data Stored in Optical Character Recognition Format, Part 1, Machine Readable Passport (6th ed. 2006), Volume 2: Specifications for Electronically Enabled Passports with Biometric Identification Capabilities (6th ed. 2006).

- ↑ "The U.S. Electronic Passport" Archived August 27, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.. Bureau of Consular Affairs, U.S. Department of State.

- ↑ "22 CFR 51.7 - Passport property of the U.S. Government.". Cornell, NY: Legal Information Institute. April 1, 2014. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- ↑ 22 U.S.C. § 2705

- ↑ "Dual Nationality".

- ↑ Lloyd, Martin, The Passport: The History of Man's Most Traveled Document (Stroud, U.K.: Sutton Publishing, 1976) (ISBN 0750929642), pp. 71-72.

- ↑ "Celebrating Black Americana" (video). video.pbs.org. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ↑ Lloyd, pp. 80-81.

- ↑ However, pursuant to the Dred Scott decision, the Secretary of State refused a passport to a black man in Massachusetts, John Rock, on grounds that, being black, he was not a United States citizen, and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts issued him a passport describing him as a citizen of the Commonwealth, and he used it to travel to Europe. "John Rock". Northwestern California University School of Law. 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ↑ Act of May 22, 1918, 40 Stat. 559; Proc. No. 1473, 40 Stat. 1829; Act of March 3, 1921, 41 Stat. 1359.

- ↑ Act of June 21, 1941, ch. 210, 55 Stat. 252; Proc. No. 2523, 55 Stat. 1696; 6 Fed. Reg. 6069 (1941).

- ↑ Haig v. Agee, 453 U.S. 280 (1981). § 707(b) of the Foreign Relations Authorization Act, Fiscal Year 1979 (Pub.L. 95–426, 92 Stat. 993, enacted October 7, 1978), amended § 215 of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 making it unlawful to enter or depart the United States without a passport even in peacetime "except as otherwise provided by the President and subject to such limitations and exceptions as the President may authorize and prescribe".

- ↑ "Passport Applications". Archives.gov. February 10, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ↑ United States Department of State, Passport Office, The United States Passport: Past, Present, Future (Washington, D.C.: United States Department of State, Passport Office, 1976), passim.

- ↑ Lloyd, p. 130.

- ↑ Lloyd, p. 155.

- ↑ "Department of State Begins Issuance of an Electronic Passport" (Press release). U.S. Department of State. February 17, 2006. Archived from the original on February 17, 2006. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- 1 2 "The U.S. Electronic Passport". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on September 6, 2010. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

Since August 2007, the U.S. has been issuing only e-passports.

- ↑ "U.S. Passport Gets a Makeover in 2016". AIGA. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ↑ Pub.L. 69–493, 44 Stat. 887, enacted July 3, 1926, currently codified at 22 U.S.C. § 211a et seq.

- ↑ currently under Executive Order 11295 of August 5, 1966 (31 FR 10603 (August 9, 1966))

- ↑ currently codified at 22 C.F.R. 51

- ↑ 7 FAM 1300

- ↑ "Regional Passport Agencies". U.S. Department of State.

- ↑ "Buffalo Passport Agency Opens". U.S. Department of State.

- ↑ "Future Passport Agencies to Meet Travel Needs of American Citizens". U.S. Department of State. June 12, 2009. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Passport Acceptance Facility Search Page". U.S. Department of State.

- ↑ "Passport Statistics". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- ↑ Regulations Concerning the Validation and Issuance of Passports for Use in European Countries, 4 FR 3892, (September 13, 1939)

- ↑ 22 C.F.R. 51.63 and 22 C.F.R. 51.64

- ↑ 22 C.F.R. 51.62

- ↑ Haig v. Agee, 453 U.S. 280 (1981), at 302

- ↑ "FOREIGN RELATIONS: Bad Ammunition". TIME Magazine. April 12, 1948.

- 1 2 "Passport Information for Criminal Law Enforcement Officers". U.S. Department of State Bureau of Consular Affairs. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Tuan Anh Nguyen v. INS, 533 U.S. 53 (2001)".

- ↑ "William Worthy, Jr., Appellant, v. United States of America, Appellee, 328 F.2d 386 (5th Cir. 1964)".

- ↑ "Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative Frequently Asked Questions" (PDF).

- ↑ "America is Testing Exit Controls at the Border".

- ↑ "Global Ranking - Visa Restriction Index 2016" (PDF). Henley & Partners. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ↑ https://www.passportindex.org/byRank.php

- ↑ http://www.psfk.com/2015/09/passport-index-visa-free-score-visualization-tool.html

- ↑ http://bgr.com/2016/03/27/passport-index-most-powerful-travel-uk-united-states/

- ↑ http://hypebeast.com/2015/4/passport-index-displays-and-ranks-passports-from-around-the-world

- ↑ Statistical Yearbook 2014 pages 91-92

- ↑ Visitor Arrivals by Country of Residence 2015

- ↑ http://members.antiguahotels.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/2015-Year-in-Review.pdf 2015 Year in Review]

- ↑ Number of Stayover Visitors by Market

- ↑ Visitors by country of residence 2015

- ↑ Tourismus in Österreich 2015

- ↑ Number of foreign citizens arrived to Azerbaijan by countries

- ↑ Stopovers by Country, table 5

- ↑

- ↑ Tourisme selon pays de provenance 2014

- ↑ Abstract of Statistics

- ↑ Visitor arrivals page 10

- ↑

- ↑ "Arrivals of informational visitors by country of residence". Archived from the original on January 3, 2016.

- ↑ "Agencija za statistiku BiH" (PDF). Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ↑ Tourism Statistics Annual Report 2014

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 25, 2016. Retrieved 2016-08-22.

- ↑

- ↑ "Arrivals of visitors from abroad to Bulgaria by months and by country of origin".

- ↑ http://www.tourismcambodia.org/images/mot/statistic_reports/tourism_statistics_2015.pdf

- ↑ Service bulletin International Travel: Advance Information, December 2015

- ↑

- ↑ Air Visitor Arrivals - Origin & General Evolution Analysis

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 27, 2016. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ↑ China Inbound Tourism in 2015

- ↑ Informes de turismo

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 12, 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

- ↑

- ↑ TOURIST ARRIVALS AND NIGHTS IN 2015

- ↑

- ↑ http://www.curacao.com/media/uploads/2016/01/22/Overall_Visitor_Arrival_Performance_December_2015.pdf Curacao Toutist Board

- ↑ "Statistical Service - Services - Tourism - Key Figures".

- ↑ Table 5 Guests, overnight stays (non-residents by country, numbers, indices)

- ↑

- ↑ Estadisticas Turisticas 2015 pages 47-48

- ↑ Statistics Netherlands

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 16, 2016. Retrieved 2016-04-02.

- ↑

- ↑ VISITOR ARRIVALS - NUMBER BY COUNTRY OF RESIDENCE, Fiji Bureau of Statistics

- ↑

- ↑ Visiteurs internationaux en France en 2014

- ↑ Nombre de touristas

- ↑ 2015 GEORGIAN TOURISM IN FIGURES STRUCTURE & INDUSTRY DATA

- ↑ Tourismus in Zahlen 2015, Statistisches Bundesamt

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- 1 2 Tourist arrivals by country of residence

- ↑ Visitor arrival statistics. Origin of air arrivals

- ↑

- ↑ Tourist arrivals by country of origin

- ↑ 2015 Visitor Arrivals Statistics

- ↑ Tourism in Hungary 2015

- ↑ "PX-Web - Select variable and values". Statistics Iceland.

- ↑ "Jumlah Kedatangan Wisatawan Mancanegara ke Indonesia Menurut Negara Tempat Tinggal 2002–2013" (in Indonesian). Statistics Indonesia (Badan Pusat Statistik). Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ↑

- ↑ Overseas Visitors to Ireland January-December 2012-2015

- ↑ VISITOR ARRIVALS(1), BY COUNTRY OF CITIZENSHIP, Central Bureau of Statistics

- ↑ IAGGIATORI STRANIERI NUMERO DI VIAGGIATORI

- ↑ Annual Travel Statistics 2015

- ↑ - 2015 Foreign Visitors & Japanese Departures, Japan National Tourism Organization

- ↑

- ↑ Visitor Arrivals by Country of Residence - Tarawa only

- ↑ Tourism in Kyrgyzstan

- ↑

- ↑ "PX-Web - Select variable and values". PX-Web.

- ↑ 2013 Visitor Arrival Statistics

- ↑

- ↑ Number of guests and overnights in Lithuanian accommodation establishments. '000. All markets. 2014-2015

- ↑ "DSEC - Statistics Database".

- ↑ Statistical review: Transport, tourism and other services

- ↑

- ↑ http://www.tourism.gov.mv/download/december-2015-update/[]

- ↑ Tourism in Malta - Statistical Report (2016 Edition)

- ↑ Number of visitors by country, 2009

- ↑

- ↑ Tourist arrivals by country of residence

- ↑ Norfi Carrodeguas. "Datatur3 - Visitantes por Nacionalidad".

- ↑

- ↑ Sosirile vizitatorilor străini în Republica Moldova şi plecările vizitatorilor moldoveni în străinătate, înregistrate la punctele de trecere ale frontierei de stat în anul 2015

- ↑ "Statistics of Tourists to Mongolia".

- ↑ Table 4. Foreign tourist arrivals and overnight stays by countries, 2014

- ↑ Tourist arrivals by country of residence

- ↑ "Myanmar Tourism Statistics 2015" (PDF). Central Statistical Organization. Ministry of National Planning and Economic Development. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- ↑

- ↑ Nepal Tourism Statistics 2015

- ↑ Inbound tourism 2014

- ↑ Statistics of New Zealand. Visitor arrivals by country of residence. United States.

- ↑ "Visitors arrival by country of residence and year".

- ↑

- ↑ Number of Tourists to Oman

- ↑ Pakistan Statistical Year Book 2012 20.31

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ The data obtained on request. Ministerio de Comercio Exterior y Turismo

- ↑

- ↑ Overnight stays in accommodation establishments in 2014 (PDF file, direct download 8.75 MB), Główny Urząd Statystyczny (Central Statistical Office (Poland)), pp. 174–177 / 254. Warsaw 2015.

- ↑

- ↑ Federal State Statistics 2015, page 126

- ↑ Entrada de Visitantes/ S. Tomé e Príncipe Ano 2005

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 24, 2016. Retrieved 2016-06-12.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Tourist turnover in the Republic of Serbia - December 2015

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 14, 2016. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- ↑ "International Visitor Arrivals". Singapore Tourism Board. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ Tourist arrivals by country of nationality

- ↑

- ↑ Slovenian Tourism in Numbers 2015

- ↑ statistics/visitor-arrivals

- ↑ http://www.sbs.gov.ws/index.php/sector-statistics/tourism-statistics?view=download&fileId=1607

- ↑

- ↑ "Korea, Monthly Statistics of Tourism - key facts on toursim - Tourism Statistics".

- ↑ Entradas de turistas según País de Residencia

- ↑ TOURIST ARRIVALS BY COUNTRY OF RESIDENCE 2015

- ↑ Tourist Arrivals By Country Of Residence 2015

- ↑ Swaziland Tourism Statistics 2015 - Arrivals by country

- ↑ "Tourism Bureau, M.O.T.C. Republic of China (Taiwan) Visitor Arrivals by Residence, 2015". admin.taiwan.net.tw. Retrieved 2015-05-28.

- ↑

- ↑ Ministry of Tourism and Sports,Thailand International Tourist Arrivals to Thailand By Nationality January - December 2015 Archived March 27, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ T&T – Stopover Arrivals By Main Markets 1995-YTD

- ↑

- ↑ Border Statistics 2015

- ↑

- ↑ Migration - Visitors by nationalities

- ↑ MINISTRY OF TOURISM, WILDLIFE AND ANTIQUITIES SECTOR STATISTICAL ABSTRACT,2014

- ↑ Foreign citizens who visited Ukraine in 2015 year, by countries

- ↑ 2.10 Number of visits to UK: by country of residence 2011 to 2015

- ↑

- ↑ TITC (December 27, 2015). "International visitors to Viet Nam in December and 12 months of 2015 - Vietnam National Administration of Tourism". Tổng cục Du lịch Việt Nam.

- ↑

- ↑ Tourism Trends and Statistics Annual Report 2014

- ↑ 22 U.S.C. sec. 212: "No passport shall be granted or issued to or verified for any other persons than those owing allegiance, whether citizens or not, to the United States." In section 212, "allegiance" means "permanent allegiance." 26 Ops. U.S. Att'y Gen. 376, 377 (1907).

- ↑ U.S. Const. amend. XIV, sec. 1.

- ↑ "Valmonte v. Immigration and Naturalization Service", 136 F.3d 914, 918 (2nd Cir. 1998).

- ↑ 8 U.S.C. secs. 1402 (Puerto Rico), 1406 (Virgin Islands), and 1407 (Guam); 48 U.S.C. sec. 1801, US-NMI Covenant sec. 303 (Northern Mariana Islands).

- ↑ 8 U.S.C. sec. 1403.

- ↑ "Citizenship and Nationality". U.S. Department Of State. Archived from the original on January 20, 2008. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ↑ 8 U.S.C. sec. 1408.

- ↑ http://www.cnn.com/2016/06/13/politics/american-samoa-citizenship-supreme-court/

- ↑ Perkins v. Elg, 307 U.S. 325 (1939).

- ↑ 8 U.S.C. sec. 1185(b).

- ↑ "US State Department Services Dual Nationality". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Certificates of non-citizen nationality". U.S. Department Of State. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ↑ 22 U.S.C. § 213

- ↑ 7 FAM 1625.5(e); 7 FAM 1636(b); 7 FAM 1351 Appendix N (a)(2).

- ↑ [travel.state.gov/passport/processing/processing_1740.html]

- ↑ "… post offices, clerks of court, public libraries and other state, county, township, and municipal government offices to accept passport applications on its behalf …" U.S. Department of State, Passport Acceptance Facility Search Page.

- ↑ "U.S. Passports & International Travel".

- ↑ "U.S. Passports & International Travel".

- ↑ "The US Passport Renewal and Special Cases Guide". UpgradedPoints.com. 2016-01-05. Retrieved 2016-05-03.

- ↑ "U.S. Passports & International Travel".

- ↑ 22 C.F.R. sec. 51.2(b).

- ↑ "Applying for a Second U.S. Passport". USEmbassy.gov. 22 C.F.R. sec. 51.4(e). Archived February 18, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions - Photo Requirements". U.S. State Department. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ↑ "Passport Photo Requirements". U.S. State Department. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ↑ "Photographers Guide". U.S. State Department. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ↑ "Photographers Guide". U.S. State Department. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Travel Fees". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ↑ "First Time Applicants". U.S. Department of State. April 1, 2001. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Processing Times". U.S. Department of State. June 16, 2008. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- 1 2 "Passport fees". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Extra Visa Pages no Longer Issued Effective January 1, 2016". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- 1 2 "Extra Visa Pages No Longer Issued Effective January 1, 2016". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved December 4, 2015.

- ↑ 22 C.F.R. secs. 51.3(a), 51.4(b)(1), 51.4(b)(2), 51.4(e).

- ↑ "Passport - Frequently Asked Questions". U.S. Department of State.

- ↑ 22 C.F.R. secs. 51.4(b)(3), 51.52, 51.4(e).

- ↑ 22 C.F.R. secs. 51.3(b), 51.4(c), 51.4(e).

- ↑ "7 FAM 1300 Appendix B endorsement codes". United States Department of State. 31 March 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ↑ 22 C.F.R. secs. 51.3(c), 51.4(d), 51.4(e).

- ↑ "Border Patrol Travel Documents, Part 14". United States Border Patrol. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ↑ "USBP Border Travel Documents, Part 13". Usborderpatrol.com. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ↑ "A Guide To Selected U.S. Travel/Identity Documents For Law Enforcement Officers". Law Enforcement Support Center, U. S. Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service. August 1, 1998. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009.

- ↑ Adjudicator's Field Manual, Section 52.2. USCIS. http://www.uscis.gov/ilink/docView/AFM/HTML/AFM/0-0-0-1/0-0-0-19929/0-0-0-19950.html

- ↑ 7 FAM sec. 1311(i); 22 C.F.R. sec. 51.4(e).

- ↑ "Replace Emergency Passport | Embassy of the United States Singapore". Singapore.usembassy.gov. June 7, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Passport Card". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- ↑ MacFarquhar, Neil (April 29, 2007). "Stars and Stripes, Wrapped in the Same Old Blue". The New York Times. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ↑ "How to Add Extra Pages to Your U.S. Passport". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on January 8, 2008. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ↑ 22 C.F.R. sec. 51.4(a).

- ↑ 7 FAM 1300 Appendix D as of April 29, 2008, including 7 FAM 1310 Appendix D through 7 FAM 1390 Appendix D.

- ↑ "7 FAM 1380 as of October 15, 1987, including 7 FAM 1381 through 7 FAM 1383" (PDF). U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 7, 2009.

- ↑ 7 FAM 1310 Appendix D as of 2008.

- ↑ 7 FAM 1380 Appendix D as of 2008 and 7 FAM 1383.6 as of 1987.

- ↑ 7 FAM 1340 Appendix D as of 2012.

- 1 2 7 FAM 1360 Appendix D as of 2008

- ↑ Kampeas, Ron. "ADL to Jerusalem-born Yanks: We Want You." Jewish Journal. July 28, 2011. July 28, 2011.

- ↑ Haaretz/Reuters/JTA, July 23, 2013, U.S. court rules || Americans born in Jerusalem cannot list 'Israel' as place of birth

- ↑ Ariane de Vogue, CNN Supreme Court Reporter (June 8, 2015). "Supreme Court strikes law in Jerusalem passport case - CNNPolitics.com". CNN.

- ↑ 7 FAM 1350 Appendix D as of 2008

- ↑ "The U.S. Electronic Passport Frequently Asked Questions". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved December 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Schneier on Security: Renew Your Passport Now!". Schneier.com. September 18, 2006. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

Bibliography

- International Civil Aviation Organization, Machine Readable Travel Documents, http://mrtd.icao.int.

- Krueger, Stephen. Krueger on United States passport law (2nd ed.). Hong Kong: Crossbow Corporation. OCLC 39139351.

- Lloyd, Martin (2008) [2003]. The Passport: The History of Man's Most Travelled Document (2nd ed.). Canterbury: Queen Anne's Fan. ISBN 978-0-9547150-3-8. OCLC 220013999.

- Salter, Mark B. (2003). Rights of Passage: The Passport in International Relations. Boulder, Co: Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58826-145-8. OCLC 51518371.

- Torpey, John C. (2000). The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State. Cambridge studies in law and society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-63249-8. OCLC 59408523.

- United States; Hunt, Gaillard (1898). The American Passport; Its History and a Digest of Laws, Rulings and Regulations Governing Its Issuance by the Department of State. Washington: Govt. print. off. OCLC 3836079.

- United States Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, Photographer's Guide. (archive)

- United States Department of State, Foreign Affairs Manual, "7 FAM Services". See 7 FAM 1300 Passport Services

- United States Department of State, Passport Office, The United States Passport: Past, Present, Future (Washington, D.C.: United States Department of State, Passport Office, 1976).

- United States Department of State, Passports, Passport Home.

- 22 C.F.R. Part 51.

- 8 U.S.C. secs. 1185, 1504.

- 18 U.S.C. secs. 1541-1547.

- 22 U.S.C. secs. 211a-218, 2705, 2721.

- U.S. Sentencing Guidelines secs. 2L2.1, 2L2.2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Passports of the United States. |

- U.S. Passport Holders By State - Map at The Huffington Post

- Fillable Form DS-11, Application for a U.S. Passport with instructions

- Fillable Form DS-82, U.S. Passport Renewal Application

- Passport ranking and list of Visa Free countries