Tynemouth

| Tynemouth | |

Tynemouth Priory |

|

Tynemouth |

|

| Population | 67,519 (2011 Town) |

|---|---|

| OS grid reference | NZ367694 |

| Metropolitan borough | North Tyneside |

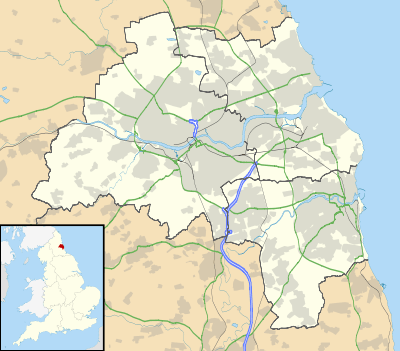

| Metropolitan county | Tyne & Wear |

| Region | North East |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | NORTH SHIELDS |

| Postcode district | NE30 |

| Dialling code | 0191 |

| Police | Northumbria |

| Fire | Tyne and Wear |

| Ambulance | North East |

| EU Parliament | North East England |

| UK Parliament | Tynemouth |

|

|

Coordinates: 55°01′N 1°25′W / 55.01°N 1.42°W

Tynemouth (/ˈtaɪnˌmaʊθ/) is a town and a historic borough in Tyne & Wear, England at the mouth of the River Tyne. The modern town of Tynemouth includes North Shields and Cullercoats and had a 2011 population of 67,519.[1] It is administered as part of the borough of North Tyneside, but until 1974 was an independent county borough, including North Shields, in its own right. It had a population of 17,056 in 2001.[2] The population of the Tynemouth ward of North Tyneside was at the 2011 Census 10,472.[3] Its history dates back to an Iron Age settlement and its strategic position on a headland over-looking the mouth of the Tyne continued to be important through to the Second World War. Its historic buildings, dramatic views and award-winning beaches attract visitors from around the world. The heart of the town, known by residents as "The village", has popular coffee-shops, pubs and restaurants. It is a prosperous area with comparatively expensive housing stock, ranging from Georgian terraces to Victorian ship-owners' houses to 1960s "executive homes". It is represented at Westminster by the Labour MP Alan Campbell.

History

The headland towering over the mouth of the Tyne has been settled since the Iron Age. The Romans occupied it. In the 7th century a monastery was built there and later fortified. The headland was known as PEN BAL CRAG

The place where now stands the Monastery of Tynemouth was anciently called by the Saxons Benebalcrag— Leland at the time of Henry VIII

The monastery was sacked by the Danes in 800, rebuilt, destroyed again in 875 but by 1083 was again operational.[4]

Three kings are reputed to have been buried within the monastery - Oswin - King of Deira (651); Osred II - King of Northumbria (792) and Malcolm III- King of Scotland (1093).[5] Three crowns still adorn the North Tyneside coat of arms. (North Tyneside Council 1990).

The queens of Edward I and Edward II stayed in the Priory and Castle while their husbands were campaigning in Scotland. King Edward III considered it to be one of the strongest castles in the Northern Marches. After Bannockburn in 1314, Edward II fled from Tynemouth by ship.

A village had long been established in the shelter of the fortified Priory and around 1325 the then Prior built a port for fishing and trading. This led to a dispute between Tynemouth and the more powerful Newcastle over shipping rights on the Tyne which continued for centuries. (For more history see North Shields).

Prince Rupert of the Rhine landed at Tynemouth in August 1642 on his way to fight in the English Civil War.[6]

Climate

Tynemouth has a very moderated oceanic climate heavily influenced by its position adjacent to the North Sea. As a result of this, summer highs are subdued and according to the Met Office 1981–2010 data around 18 °C (64 °F). As a consequence of its marine influence, winter lows especially are very mild for a Northern English location. Sunshine levels of 1515 hours per annum are in the normal range for the coastal North East, which is also true for the relatively low amount of precipitation at 597.2 millimetres (23.51 in).[7]

| Climate data for Tynemouth 33m asl, 1981–2010 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.2 (45) |

7.3 (45.1) |

9.0 (48.2) |

10.3 (50.5) |

12.7 (54.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

18.1 (64.6) |

18.1 (64.6) |

16.1 (61) |

13.2 (55.8) |

9.7 (49.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

12.1 (53.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.2 (36) |

2.2 (36) |

3.3 (37.9) |

4.8 (40.6) |

7.2 (45) |

10.0 (50) |

12.3 (54.1) |

12.3 (54.1) |

10.4 (50.7) |

7.7 (45.9) |

4.9 (40.8) |

2.5 (36.5) |

6.7 (44.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 45.5 (1.791) |

37.8 (1.488) |

43.9 (1.728) |

45.4 (1.787) |

43.2 (1.701) |

51.9 (2.043) |

47.6 (1.874) |

59.6 (2.346) |

53.0 (2.087) |

53.6 (2.11) |

62.8 (2.472) |

53.9 (2.122) |

597.2 (23.512) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 61.1 | 81.6 | 117.7 | 149.9 | 191.7 | 183.0 | 185.7 | 174.9 | 174.1 | 106.2 | 70.4 | 51.9 | 1,515 |

| Source: Met Office[7] | |||||||||||||

About Tynemouth

Beaches

In the late 18th century, sea-bathing became fashionable in Tynemouth from its east-facing beaches. King Edward's Bay and Tynemouth Longsands are very popular with locals and tourists alike.

Prior's Haven is a small beach within the mouth of the Tyne, sheltered between the Priory and the Spanish Battery, with the Pier access on its north side. It was popular with Victorian bathers[8] and is now home to Tynemouth Rowing Club and the local sailing club.

King Edward's Bay (possibly a reference to Edward II) is a small beach on the north side of the Priory, sheltered on three sides by cliffs and reached by stairways, or, by the fit and adventurous who understand the weather and tides, over the rocks round the promontories on the north or south sides.

Longsands is the next beach to the north, an expanse of fine sand 1200 yards long, lying between the former Tynemouth outdoor swimming pool and Cullercoats to the north.

In 2013, Longsands was voted one of the best beaches in the country by users of the world’s largest travel site TripAdvisor. TripAdvisor users have voted the beach the UK’s fourth favourite beach in its 2013 Travellers’ Choice Beaches Awards, beaten only by Rhossili Bay in Wales, Woolacombe Beach in North Devon and Porthminster Beach at St Ives, Cornwall. The beach was also voted the 12th best in Europe.[9]

Front Street

A statue of Queen Victoria by Alfred Turner, unveiled on 25 October 1902, is situated at the edge of the Village Green[10] which is home to the War Memorials for the residents of Tynemouth lost during the Second Boer War of 1899-1902. Designed by A.B. Plummer, it was unveiled on 13 October 1903 by William Brodrick, 8th Viscount Midleton.

The larger central memorial is made of white granite with a cruciform column rising from between four struts in a contemporary design for its time. The front face has a relief sword and wreath carved onto it with the inscription below. The other three faces hold the honour roll for those lost during both World Wars. It was unveiled in 1923. DM O'Herlihy was named as the original designer but a press report stated that a Mr Steele designed the monument and credited O'Herlihy with preparatory works on the village green.[11] The 82 names from World War II were added in 1999.[12]

Maintaining transport links between Tynemouth and Newcastle is Tynemouth Metro station, originally opened in 1882 as a mainline station catering for the thousands of holiday-makers who flocked to the Tynemouth beaches. Its ornate Victorian ironwork canopies have earned it Grade II listed status. They were restored in 2012, and the station now provides a venue for a weekend "flea market", book fairs, craft displays, coffee shops, restaurants, exhibitions and other events.[13]

Kings Priory School

Located on Huntington Terrace, Kings Priory School (formerly The King's School) is a co-educational academy with over 800 pupils aged between 4 and 18. Though founded in Jarrow in 1860, the school moved to its present site in Tynemouth in 1865 originally providing a private education for local boys. The school has an Anglican tradition, but admits students of all faiths. Formerly a fee-paying independent school, in 2013 the school merged with the comprehensive Priory School to become a state academy.

Former King's School was named in reference to the three ancient kings buried at Tynemouth Priory: Oswin, Osred and Malcolm III. Its most famous old boy is Stan Laurel, one half of the comedy duo Laurel and Hardy.[14] Hollywood film director Sir Ridley Scott, and racing driver Jason Plato also attended the school.

Tynemouth Pier and lighthouse

| |

| Location | Tynemouth |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 55°00′52″N 1°24′10″W / 55.014559°N 1.402897°W |

| Year first constructed | 1864 (first) |

| Year first lit | 1903 (current) |

| Construction | stone tower |

| Tower shape | tapered cylindrical tower with balcony and lantern |

| Markings / pattern | unpainted tower, white lantern |

| Height | 23 metres (75 ft) |

| Focal height | 26 metres (85 ft) |

| Current lens | rotating catadioptric lens (6 panels in 2 groups of 3) |

| Light source | mains power |

| Range | 26 nmi (48 km; 30 mi) |

| Characteristic | Fl (3) W 10s. |

| Fog signal | 1 blast every 10s. |

| Admiralty number | A2700 |

| NGA number | 2104 |

| ARLHS number | ENG-159 |

| Managing agent | Port of Tyne[15] |

This massive stone breakwater extends from the foot of the Priory some 900 yards (810 metres) out to sea, protecting the northern flank of the mouth of the Tyne. It has a broad walkway on top, popular with Sunday strollers. On the lee side is a lower level rail track, formerly used by trains and cranes during the construction and maintenance of the pier. At the seaward end is a lighthouse.

The pier's construction took over 40 years (1854–1895).[16] In 1898 the original curved design proved inadequate against a great storm and the centre section was destroyed. The pier was rebuilt in a straighter line and completed in 1909.[17] A companion pier at South Shields protects the southern flank of the river mouth.

A lighthouse was built on the North Pier in 1864, but when the pier had to be rebuilt to a new design a new lighthouse was required. The work was undertaken by Trinity House, beginning in 1903; the lighthouse was finished before the pier itself, and was first lit on 15 January 1908.[18] It remains in use today.

Before the pier was built, a lighthouse stood within the grounds of Tynemouth Priory and Castle. It was demolished in 1898-99. It stood on the site of the now-disused Coastguard Station.

The Spanish Battery

The headland dominates the river mouth and is less well known as Freestone Point. Settlements dating from the Iron Age and later have been discovered here.[19] The promontory supposedly takes its name from Spanish mercenaries who manned guns there in the 16th century to defend Henry VIII's fleet. Most of the guns had been removed by 1905.[20] It is now a popular vantage point for watching shipping traffic on the Tyne.

The Collingwood Monument

.jpg)

Beyond the Battery and commanding the attention of all shipping on the Tyne is the giant memorial to Lord Collingwood, Nelson's second-in-command at Trafalgar, who completed the victory after Nelson was killed. Erected in 1845, the monument was designed by John Dobson and the statue was sculpted by John Graham Lough. The figure is some 23 feet (7.0 m) tall and stands on a massive base incorporating a flight of steps flanked by four cannons from The Royal Sovereign - Collingwood's ship at Trafalgar.[21]

The Black Middens

These rocks in the Tyne near the Monument are covered at high water, and the one rock that can sometimes be seen is called Priors Stone. Over the centuries they have claimed many ships who "switched off" after safely negotiating the river entrance. In 1864, the Middens claimed five ships in three days with many deaths, even though the wrecks were only a few yards from the shore. In response a meeting was held in North Shields Town Hall in December 1864 at which it was agreed that a body of men should be formed to assist the Coastguard in the event of such disasters. This led to the foundation of the Tynemouth Volunteer Life Brigade.[16]

Religion

Tynemouth's Parish Church is the Church Of The Holy Saviour in the Parish of Tynemouth Priory. It was built in 1841[22] as a chapel of ease to the main Anglican church in the area, Christ Church, North Shields. In Front Street there were two other churches, the Catholic Parish of Our Lady & St Oswins,[23] opened in 1899, and also Tynemouth Congregational Church, which closed in 1973[24] and is now a shopping arcade.

Sea to Sea Cycle Route

Tynemouth is the end point for the 140 miles (230 km) long Sea to Sea Cycle Route from Whitehaven or Workington in Cumbria.[25]

Blue Reef Aquarium

Undersea aquatic park, containing seahorses, sharks, giant octopus, frogs, otters and many other creatures. Its Seal Cove is a purpose-built outdoor facility providing an environment for a captive-bred colony of harbour seals.

The 500,000-litre pool includes rocky haul-out areas and underwater caves, specially created to ensure marine mammals are kept in near natural conditions.

A ramped walkway and viewing panels have been provided so visitors have an opportunity to admire the creatures from both above and below the waterline.

Demography

In 2011, Tynemouth had a population of 67,519, compared to 17,056 a decade earlier.[26] This is because of boundary changes rather than an actual population increase, for example, North Shields was a separate urban subdivision in 2001 and had a population of over 36,000. Shiremoor was also a different urban subdivision, with a population of almost 5000 in 2001.[26] The 2011 definition of the town of Tynemouth includes North Shields and Cullercoats along with some areas in the north west of the town such as Shiremoor or West Allotment. However using 2011 methodology boundaries Tynemouth had a population of 60,881 in 2001 (this is not the actual 2001 population of Tynemouth, just the population of the 2011 boundaries in the 2001 census). This means that Tynemouth has become a larger area in both size and population means.[27]

| Tynemouth compared 2011 | Tynemouth Urban Subdivision | North Tyneside |

|---|---|---|

| White British | 94.7% | 95.1% |

| Asian | 2.0% | 1.9% |

| Black | 0.3% | 0.4% |

In 2011, 5.3% of Tynemouth's population was non white british, compared to 4.9% for the surrounding borough. North Tyneside is the least ethnically diverse borough in Tyne and Wear and is the fifth least ethnically diverse Metropolitan borough in the country. Tynemouth is one of the least ethnically diverse major towns in the county, however Whitley Bay, which is just to the north, has even less ethnic minorities.

Notable residents

- Susan Mary Auld - naval architect[30]

- Thomas Bewick - engraver, spent many holidays at Bank Top and wrote most of his memoirs there in 1822

- Septimus Brutton - played a single first-class cricket match for Hampshire in 1904

- Harriet Martineau - novelist and journalist, lived at 57 Front Street 1840-45, now The Martineau Guest House named in her honour. She wrote three books here and some hundred pages of her autobiography are devoted to the Tynemouth period. Her eminent visitors included Richard Cobden and Thomas Carlyle. Carlyle (a Scotsman) considered that Tynemouth residents were Scottish in their features, character and dialect.

- Giuseppe Garibaldi - sailed into to the mouth of the River Tyne in 1854 and briefly stayed in Huntingdon Place. The house is marked by a commemorative plaque.[31]

- Andy Taylor - former lead guitarist for the new wave group Duran Duran, was born and raised in Tynemouth, the son of a fisherman who raised him as a single parent after Taylor's mother abandoned the family.[32]

- Henry Treece - Poet, childrens' author and editor, spent 1935-38 teaching at Tynemouth School for Boys. He certainly wrote one story set locally, The Black Longship in his collection The Invaders

- Ridley Scott - film director, was a pupil at The King's School

- Toby Flood - England rugby player, was a pupil at The King's School

- Ronald (Ronnie) Harker - born in Tynemouth - the man who put the Merlin in the Mustang

Notable visitors

Charles Dickens visited Tynemouth and wrote in a letter from Newcastle, dated 4 March 1867:

'We escaped to Tynemouth for a two hours' sea walk. There was a high wind blowing, and a magnificent sea running. Large vessels were being towed in and out over the stormy bar with prodigious waves breaking on it; and, spanning the restless uproar of the waters, was a quiet rainbow of transcendent beauty. the scene was quite wonderful. We were in the full enjoyment of it when a heavy sea caught us, knocked us over, and in a moment drenched us and filled even our pockets.'

Lewis Carroll states in the first surviving diary of his early manhood, that he met 'three nice little children' belonging to a Mrs Crawshay in Tynemouth on 21 August 1855. He remarks: 'I took a great fancy to Florence, the eldest, a child of very sweet manners'.

Algernon Charles Swinburne arrived hot foot from Wallington Hall in December 1862 and proceeded to accompany William Bell Scott and his guests, probably including Dante Gabriel Rossetti on a trip to Tynemouth. Scott writes that as they walked by the sea, Swinburne declaimed his Hymn to Proserpine and Laus Veneris in his strange intonation, while the waves ‘were running the whole length of the long level sands towards Cullercoats and sounding like far-off acclamations’.

Peter the Great of Russia is reputed to have stayed briefly in Tynemouth while on an incognito visit to learn about shipbuilding on the Tyne. He was fascinated by shipbuilding and Western life. Standing 6 feet 8 inches (203 cm) and with body-guards, he would not have been troubled by the locals.[33]

Festivals

Mouth of Tyne festival

The Mouth of the Tyne Festival currently continues the local festival tradition. This annual free festival is held jointly between Tynemouth and South Shields and includes a world-class open-air concert at Tynemouth Priory.

Tynemouth pageant

Tynemouth Pageant is a community organisation in North Tyneside, Tyne and Wear, England, devoted to staging an open-air dramatic pageant every three years in the grounds of Tynemouth Castle and Priory, by kind permission of English Heritage who run the historic monastic and defensive site at the mouth of the River Tyne.[34]

In popular culture

- Many of the books of prize-winning children's author Robert Westall are set in Tynemouth.[17]

- The Fire Worm. London: Gollancz, 1988. ISBN 0-575-04300-8, a book by prize-winning science fiction author Ian Watson is set in Tynemouth, and is based on the Lambton Worm legend.

- The 80's television series Supergran was predominantly filmed in Tynemouth and the flying bicycle and other artefacts used in filming were until 2006 on permanent display in the Land of Green Ginger (converted Congregational Church) on Front Street.[17]

- Much of the 2004/5 BBC television series 55 Degrees North, starring Don Gilet and Dervla Kirwan was filmed in and around Tynemouth, including the location of Nicky and Errol's houses.

- In the 2005 film Goal!, the lead character played by Kuno Becker trains by running along Tynemouth Longsands.

- Many scenes from the 1961 film "Payroll" are set in Tynemouth.

- Tynemouth is mentioned in an episode of the American comedy series "The Mindy Project" in an insult from Dr. Reed to his neighbor. "You have the manners of a Blackpool dockjob"? What the hell does that even mean? It's like a Tynemouth stevedore only ruder".

- A short Manga comic, written by Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki, entitled A Trip To Tynemouth was released in 2006.[35]

See also

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Tynemouth. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tynemouth. |

References

- ↑ http://www.citypopulation.de/php/uk-england-northeastengland.php?cityid=E35001354

- ↑ Office for National Statistics : Census 2001 : Urban Areas : Table KS01 : Usual Resident Population Retrieved 2009-08-26

- ↑ "North Tyneside ward population 2011". Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ↑ Pevsner, Buildings of England, Northumberland

- ↑ https://www.hodstw.org.uk/north_tyneside_history

- ↑ Spencer, Charles (2015). Prince Rupert: The Last Cavalier. W&N. p. 55. ISBN 0-753-82401-9.

- 1 2 "Tynemouth climate information". Met Office. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ↑ Henderson, Tony. "Still guarding River Tyne a century after repairs". The Journal. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

- ↑ Chronicle, Evening. "Tynemouth beach voted one of UK's best". Chronicle Live. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

- ↑ "PMSA". PMSA. 1902-10-25. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

- ↑ "North East War Memorials Project". Newmp.org.uk. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

- ↑ "War Memorials Trust". Warmemorials.org. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

- ↑ "Before and after: historic buildings restored and transformed". Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ Henderson, Tony (2014-09-15). "Stan Laurel's letter to his friend's wife on Tyneside goes under the hammer". The Journal. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

- ↑ Tynemouth (Tyne North Pier) The Lighthouse Directory. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved May 6, 2016

- 1 2 "Heroes and Shipwrecks - North Tyneside Council". Northtyneside.gov.uk. 1999-07-01. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

- 1 2 3 http://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/local-news/ten-interesting-facts-tynemouth--1342151

- ↑ Jones, Robin (2014). Lighthouses of the North East Coast. Wellington, Somerset: Halsgrove.

- ↑ Jobey, G 1967 `Excavation at Tynemouth Priory and Castle [Normumberland]' Archaeol Aeliana

- ↑ "Priors, Kings and Soldiers - North Tyneside Council". Northtyneside.gov.uk. 1999-07-01. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

- ↑ Pevsner: Buildings of England, Northumberland

- ↑ "Holy Saviours - Our Story". The Church Of The Holy Saviour Tynemouth Priory.

- ↑ "The Parish of Our Lady & St. Oswin's, Tynemouth and St Mary's, Cullercoats Welcome". Tynemouth & Cullercoats Catholics.

- ↑ "The United Reformed Church In North Shields - Church History". St Columba's URC.

- ↑ Coast to Coast guide

- 1 2 Office for National Statistics : Census 2001 Key Statistics - Urban areas in the North Part 1 Retrieved 2014-10-11

- ↑ "Tynemouth (Tyne and Wear, North East England, United Kingdom) - Population Statistics and Location in Maps and Charts". www.citypopulation.de. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- ↑ https://www.nomisweb.co.uk/census/2011/ks201ew

- ↑ http://www.ukcensusdata.com/north-tyneside-e08000022#sthash.C7MTghix.dpbs

- ↑ Henderson, Tony. "Tyneside shipbuilding history is saved from dumpster". Chronicle Live. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

- ↑ "Giuseppe Garibaldi blue plaque". Openplaques.org. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

- ↑ De Graaf, Kasper, and Garrett, Malcolm. Duran Duran: Their Story. Published in 1982.

- ↑ Story told by Russian guide in St. Petersberg, 1998

- ↑ Archived 26 March 2005 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "In Case You're Wondering What Hayao Miyazaki Is Up To... | Kotaku Australia". Kotaku.com.au. 2014-12-02. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

External links

- Tynemouth, in video and pictures (personal website)

- Tynemouth Priory at the English Heritage website

- A guide to Tynemouth market

- Tynemouth shops, bars, cafes and events