Twelve Days of Christmas

| Twelve Days of Christmas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Observed by | Christians |

| Type | Christian |

| Observances | varies by church, culture, country |

| Date | 25/26 December – 5/6 January |

| Frequency | annual |

| Related to | Christmas Day, Christmastide, Twelfth Night, Epiphany, Epiphanytide |

The Twelve Days of Christmas, also known as Twelvetide, is a festive Christian season to celebrate the nativity of Jesus. In most Western Church traditions Christmas Day is the First Day of Christmas and the Twelve Days are 25 December – 5 January.[1] For many Christian denominations, such as the Anglican Communion and Lutheran Church, the Twelve Days period is the same as Christmastide;[2][3][4] for others, such as the Catholic Church, Christmastide lasts a little longer;[5] the Twelve Days are different from the Octave of Christmas, which is the eight-day period from Christmas Day until 1 January. In Anglicanism, the term "Twelve Days of Christmas" is used liturgically in the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America, having its own invitatory antiphon in the Book of Common Prayer for Matins.[3]

Eastern Christianity

Since Armenian Apostolic and Armenian Catholic Christians celebrate the birth and the baptism of Christ on the same day,[6] they do not have a series of twelve days between a Christmas feast and an Epiphany feast.

The Oriental Orthodox, other than the Armenians, and the Eastern Orthodox, as well as the Eastern Catholics who follow the same traditions, do have the twelve-day interval between the two feasts. If they use the Julian calendar, they have Christmas on what is for them 25 December but for others 7 January, and they have Epiphany on what for them is 6 January but for others 19 January.

Eastern Orthodox

For the Eastern Orthodox, both Christmas and Epiphany are among the Twelve Great Feasts that come next after Easter in importance.[7]

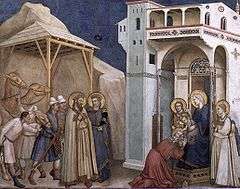

The period between Christmas and Epiphany is fast-free.[7] During this period one celebration leads into another. The Nativity of Christ is a three-day celebration: the formal title of the first day is "The Nativity According to the Flesh of our Lord, God and Saviour Jesus Christ", and celebrates not only the Nativity of Jesus, but also the Adoration of the Shepherds of Bethlehem and the arrival of the Magi; the second day is referred to as the "Synaxis of the Theotokos", and commemorates the role of the Virgin Mary in the Incarnation; the third day is known as the "Third Day of the Nativity", and is also the feast day of the Protodeacon and Protomartyr Saint Stephen.

29 December is the Orthodox Feast of the Holy Innocents.

The Afterfeast of the Nativity (similar to the Western octave) continues until 31 December (that day is known as the Apodosis or "leave-taking" of the Nativity).

The Saturday following the Nativity is commemorated by special readings from the Epistle (1 Tim 6:11-16) and Gospel (Matt 12:15-21) during the Divine Liturgy. The Sunday after Nativity has its own liturgical commemoration in honour of "The Righteous Ones: Joseph the Betrothed, David the King and James the Brother of the Lord".

Another of the more prominent festivals that are included among the Twelve Great Feasts is that of the Circumcision of Christ (1 January).[7] On this same day is the feast day of Saint Basil the Great, and so the service celebrated on that day is the Divine Liturgy of Saint Basil.

2 January begins the Forefeast of the Theophany.

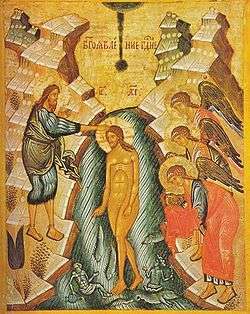

The Eve of the Theophany (5 January) is a day of strict fasting, on which the devout will not eat anything until the first star is seen at night. This day is known as Paramony ("preparation"), and follows the same general outline as Christmas Eve. That morning is the celebration of the Royal Hours and then the Divine Liturgy of Saint Basil combined with Vespers, at the conclusion of which is celebrated the Great Blessing of Waters, in commemoration of the Baptism of Jesus in the Jordan River. There are certain parallels between the hymns chanted on Paramony and those of Good Friday, to show that, according to Orthodox theology, the steps that Jesus took into the Jordan River were the first steps on the way to the Cross. That night the All-Night Vigil is served for the Feast of the Theophany.

Western Christianity

Within the Twelve Days of Christmas, there are celebrations both secular and religious.

Christmas Day, if it is considered to be part of the Twelve Days of Christmas and not as the day preceding the Twelve Days,[2] is celebrated by Christians as the liturgical feast of the Nativity of the Lord. It is a public holiday in many countries, including some where the majority of the population is not Christian. On this see the articles on Christmas and on Christmas traditions.

In the United States, Christmas is a holiday for Christians and for some non-Christians.[8] In India, although non-Christians such as Hindus and Muslims do not celebrate Christmas, the holiday is known as Bara Din (Hindustani: बड़ा दिन (Devanagari), بڑا دن (Nastaleeq)), meaning The Great Day.[9]

December 26 is St. Stephen's Day, a saint's feast day in the Western Church. In Britain and its former colonies, it is also the secular holiday of Boxing Day. In some parts of Ireland it is known as Wren Day.

New Year's Eve on 31 December is the feast of Saint Sylvester and is known also as Silvester. The transition that evening to the new year is an occasion for secular festivities in many countries,and in several languages is known by names such as Saint Sylvester Night: Notte di San Silvestro in Italian, Silvesternacht in German, Réveillon de la Saint-Sylvestre in French, סילבסטר in Hebrew.

New Year's Day on 1 January is an occasion for further secular festivities or for rest from the celebrations of the night before. Liturgically it is, for the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church, the Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God celebrated on the Octave Day of Christmas. It has also been celebrated and still is in some denominations as the Feast of the Circumcision of Christ, since by Jewish tradition he must have been circumcised on the eighth day (counting both the first day and the end day) after his birth. This day or some day close to it is also celebrated as the World Day of Peace by the popes and Catholic groups.[10]

In many countries Epiphany is now celebrated on the first Sunday after 1 January, which can fall as early as 2 January. That feast, then, together with customary observances associated with it, most often fall within the Twelve Day of Christmas, even if these are considered as ending on 5 January rather than 6 January.

Other liturgical feasts that fall within the Octave of Christmas and so also within the Twelve Days of Christmas and that are included in the General Roman Calendar are: Saint John the Apostle (27 December); the Holy Innocents (28 December); Saint Thomas Becket (29 December); and the Feast of the Holy Family (Sunday within the Octave of Christmas or, if there is no such Sunday, 30 December). Outside the Octave, but within the Twelve Days of Christmas, there are the celebrations of Saints Basil the Great and Gregory of Nazianzus on 2 January, and the Memorial of the Holy Name of Jesus on 3 January.

Other saints are celebrated at a local level.

Late Antiquity and Middle Ages

The Second Council of Tours of 567 noted that, in the area for which its bishops were responsible, the days between Christmas and Epiphany were, like the month of August, taken up entirely with saints' days. Monks were therefore in principle not bound to fast on those days.[11] However, the first three days of the year were to be days of prayer and penance so that faithful Christians would refrain from participating in the idolatrous practices and debauchery associated with the new year celebrations. The Fourth Council of Toledo (633) ordered a strict fast on those days, on the model of the Lenten fast.[12][13]

England

_-_Twelfth-night_(The_King_Drinks)_-_WGA22083.jpg)

In England in the Middle Ages, this period was one of continuous feasting and merrymaking, which climaxed on Twelfth Night, the traditional end of the Christmas season. In Tudor England, Twelfth Night itself was forever solidified in popular culture when William Shakespeare used it as the setting for one of his most famous stage plays, titled Twelfth Night. Often a Lord of Misrule was chosen to lead the Christmas revels.[14]

Some of these traditions were adapted from the older pagan customs, including the Roman Saturnalia and the Germanic Yuletide.[15] Some also have an echo in modern-day pantomime where traditionally authority is mocked and the principal male lead is played by a woman, while the leading older female character, or 'Dame', is played by a man.

Colonial America

The early North American colonists brought their version of the Twelve Days over from England, and adapted them to their new country, adding their own variations over the years. For example, the modern-day Christmas wreath may have originated with these colonials.[16][17] A homemade wreath would be fashioned from local greenery and fruits, if available, were added. Making the wreaths was one of the traditions of Christmas Eve; they would remain hung on each home's front door beginning on Christmas Night (1st night of Christmas) through Twelfth Night or Epiphany morning. As was already the tradition in their native England, all decorations would be taken down by Epiphany morning and the remainder of the edibles would be consumed. A special cake, the king cake, was also baked then for Epiphany.

Modern Western customs

United Kingdom and Commonwealth

Many in the UK and other Commonwealth nations still celebrate some aspects of the Twelve Days of Christmas. Boxing Day, 26 December, is a national holiday in many Commonwealth nations. Victorian era stories by Charles Dickens, and others, particularly A Christmas Carol, hold key elements of the celebrations such as the consumption of plum pudding, roasted goose and wassail. These foods are consumed more at the beginning of the Twelve Days in the UK.

Twelfth Night is the last day for decorations to be taken down, and it is held to be bad luck to leave decorations up after this.[18] This is in contrast to the custom in Elizabethan England, when decorations were left up until Candlemas; this is still done in some other Western European countries such as Germany.

United States

The traditions of the Twelve Days of Christmas have been largely forgotten in the United States. Contributing factors include the popularity of stories by Charles Dickens in nineteenth-century America (with their emphasis on generous gift-giving), introduction of more secular traditions over the past two centuries (such as the American Santa Claus), and the rise in popularity of New Year's Eve parties. The first day of Christmas actually terminates the Christmas marketing season for merchants, as shown by the number of "after-Christmas sales" that launch on 26 December. The commercial calendar has encouraged an erroneous assumption that the Twelve Days end on Christmas Day and must therefore begin on 14 December.[19]

Many Christians still celebrate the liturgical seasons of Advent and Christmas according to their traditions. Represented well among these are Orthodox Christians, Catholics, Episcopalians, Anglo-Catholics, Lutherans, many Presbyterians and Methodists, Moravians, and many individuals in Amish and Mennonite communities.

Celebrants observing the Twelve Days may give gifts on each of them, with each day of the Twelve Days representing a wish for a corresponding month of the new year. They feast and otherwise celebrate the entire time through Epiphany morning. Lighting a candle for each day has become a modern tradition in the U.S. and of course singing the appropriate verses of the famous song each day is also an important and fun part of the American celebrations. Some also light a Yule Log on the first night (Christmas) and let it burn some each of the twelve nights. Some Americans have their own traditional foods to serve each night.

For some, Twelfth Night remains the biggest night for parties and gift-giving. Some households exchange gifts on the first (25 December) and last (5 January) days of the season. As in olden days, Twelfth Night to Epiphany morning is then the traditional time to take down the Christmas tree and decorations.

References

- ↑ Hatch, Jane M. (1978). The American Book of Days. Wilson. ISBN 9780824205935.

January 5th: Twelfth Night or Epiphany Eve. Twelfth Night, the last evening of the traditional Twelve Days of Christmas, has been observed with festive celebration ever since the Middle Ages.

- 1 2 Bratcher, Dennis (10 October 2014). "The Christmas Season". Christian Resource Institute. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

The Twelve Days of Christmas ... in most of the Western Church are the twelve days from Christmas until the beginning of Epiphany (January 6th; the 12 days count from December 25th until January 5th). In some traditions, the first day of Christmas begins on the evening of December 25th with the following day considered the First Day of Christmas (December 26th). In these traditions, the twelve days begin December 26 and include Epiphany on January 6.

- 1 2 "The Book of Common Prayer" (PDF). New York: Church Publishing Incorporated. January 2007. p. 43. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

On the Twelve Days of Christmas Alleluia. Unto us a child is born: O come, let us adore Him. Alleluia.

- ↑ Truscott, Jeffrey A. Worship. Armour Publishing. p. 103. ISBN 9789814305419.

As with the Easter cycle, churches today celebrate the Christmas cycle in different ways. Practically all Protestants observe Christmas itself, with services on 25 December or the evening before. Anglicans, Lutherans and other churches that use the ecumenical Revised Common Lectionary will likely observe the four Sundays of Advent, maintaining the ancient emphasis on the eschatological (First Sunday), ascetic (Second and Third Sundays), and scriptural/historical (Fourth Sunday). Besides Christmas Eve/Day, they will observe a 12-day season of Christmas from 25 December to 5 January.

- ↑ Universal Norms on the Liturgical Year, 33

- ↑ Kelly, Joseph F (2010). Joseph F. Kelly, The Feast of Christmas (Liturgical Press 2010 ISBN 978-0-81463932-0). ISBN 9780814639320.

- 1 2 3 Kallistos Ware, The Orthodox Church

- ↑ Sirvaitis, Karen (1 August 2010). The European American Experience. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 52. ISBN 9780761340881.

Christmas is a major holiday for Christians, although some non-Christians in the United States also mark the day as a holiday.

- ↑ Labaree, Mary Schauffler (1914). The Child in the Midst. The Central Committee on the United Study of Foreign Missions, West Medlock, Massachusetts. p. 954.

Few of those who live in a Christian land can realize the effect of the mere observance of the Christmas festival on those who never heard of Christ. Christmas Day, although of course not celebrated by non-Christians, is nevertheless called in India "the great day of the year" by thousands of Hindus and Mohammedans.

- ↑ United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, "World Day of Peace"

- ↑ Jean Hardouin; Philippe Labbé; Gabriel Cossart (1714). "Christmas". Acta Conciliorum et Epistolae Decretales (in Latin). Typographia Regia, Paris. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

De Decembri usque ad natale Domini, omni die ieiunent. Et quia inter natale Domini et epiphania omni die festivitates sunt, itemque prandebunt. Excipitur triduum illud, quo ad calcandam gentilium consuetudinem, patres nostri statuerunt privatas in Kalendariis Ianuarii fieri litanias, ut in ecclesiis psallatur, et hora octava in ipsis Kalendis Circumcisionis missa Deo propitio celebretur. (Translation: "In December until Christmas, they are to fast each day. Since between Christmas and Epiphany there are feasts on each day, they shall have a full meal, except during the three-day period on which, in order to tread Gentile customs down, our fathers established that private litanies for the Calends of January be chanted in the churches, and that on the Calends itself Mass of the Circumcision be celebrated at the eighth hour for God's favour.")

- ↑ Christopher Labadie, "The Octave Day of Christmas: Historical Development and Modern Liturgical Practice" in Obsculta, vol. 7, issue 1, art. 8, p. 89

- ↑ Adolf Adam, The Liturgical Year (Liturgical Press 1990 ISBN 978-0-81466047-8), p. 139

- ↑ Frazer, James (1922). The Golden Bough. New York: McMillan. ISBN 1-58734-083-6. Bartleby.com

- ↑ Count, Earl (1997). 4,000 Years of Christmas. Ulysses Press. ISBN 1-56975-087-4.

- ↑ New York Times, 27 December 1852: a report of holiday events mentions 'a splendid wreath' as being among the prizes won.

- ↑ In 1953 a correspondence in the letter pages of The Times discussed whether Christmas wreaths were an alien importation or a version of the native evergreen 'bunch'/'bough'/'garland'/'wassail bush' traditionally displayed in England at Christmas. One correspondent described those she had seen placed on doors in country districts as either a plain bunch, a shape like a torque or open circle, and occasionally a more elaborate shape like a bell or interlaced circles. She felt the use of the words 'Christmas wreath' had 'funereal associations' for English people who would prefer to describe it as a 'garland'. An advertisement in The Times of Friday, 26 December 1862; pg. 1; Issue 24439; col A, however, refers to an entertainment at Crystal Palace featuring 'Extraordinary decorations, wreaths of evergreens ...', and in 1896 the special Christmas edition of The Girl's Own Paper was titled 'Our Christmas Wreath':The Times Saturday, 19 December 1896; pg. 4; Issue 35078; col C. There is a custom of decorating graves at Christmas with somber wreaths of evergreen, which is still observed in parts of England, and this may have militated against the circle being the accepted shape for door decorations until the re-establishment of the tradition from America in the mid-to-late 20th century.

- ↑ http://www.timeanddate.com/holidays/uk/epiphany

- ↑ HumorMatters.com Twelve Days of Christmas (reprint of a magazine article). Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- "Christmas". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 22 December 2005. Primarily subhead Popular Merrymaking under Liturgy and Custom.

- "The Twelve Days of Christmas". Catholic Culture. Retrieved 22 January 2012. Primarily subhead 12 Days of Christmas under Catholic and Culture.

- Bowler, Gerald (2000). The World Encyclopedia of Christmas. Toronto: M&S. ISBN 978-0-7710-1531-1. OCLC 44154451.

- Caulkins, Mary; Jennie Miller Helderman (2002). Christmas Trivia: 200 Fun & Fascinating Facts About Christmas. New York: Gramercy. ISBN 978-0-517-22070-2. OCLC 49627774.

- Collins, Ace; Clint Hansen (2003). Stories Behind the Great Traditions of Christmas. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-24880-4. OCLC 52311813.

- Evans, Martin Marix (2002). The Twelve Days of Christmas. White Plains, New York: Peter Pauper Press. ISBN 978-0-88088-776-2. OCLC 57044650.

- Wells, Robin Headlam (2005). Shakespeare's Humanism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82438-5. OCLC 62132881.

- Hoh, John L., Jr. (2001). The Twelve Days of Christmas: A Carol Catechism. Vancouver: Suite 101 eBooks.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Christmastide. |

| Look up Twelve Days of Christmas in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |