Tuscan dialect

| Tuscan | |

|---|---|

| Toscano | |

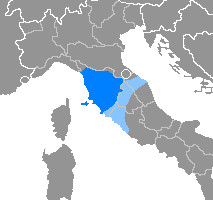

| Native to | Italy and France |

| Region |

Tuscany (except the Province of Massa-Carrara) Umbria (western border with Tuscany) Corsica, Haute-Corse (as a variety) Sardinia, Gallura (as a variety) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

Linguist list |

ita-tus |

| Glottolog | None |

| Linguasphere |

51-AAA-qa |

| |

| |

| Part of a series on the |

| Italian language |

|---|

| History |

| Literature and other |

| Grammar |

| Alphabet |

| Phonology |

Tuscan (dialetto toscano [di.aˈlɛtto toˈskaːno; dja-]) is an Italo-Dalmatian variety mainly spoken in Tuscany, Italy.

Standard Italian is based on Tuscan, specifically on its Florentine dialect. Italian became the language of culture for all the people of Italy[1] thanks to the prestige of the masterpieces of Dante Alighieri, Petrarch, Giovanni Boccaccio, Niccolò Machiavelli and Francesco Guicciardini. It would later become the official language of all the Italian states and of the Kingdom of Italy when it was formed.

Subdialects

Tuscan is a dialect complex composed of many local variants, with minor differences among them.

The main subdivision is between Northern Tuscan dialects and Southern Tuscan dialects.

The Northern Tuscan dialects are (from east to west):

- Fiorentino, the main dialect of Florence, Chianti and the Mugello region, also spoken in Prato and along the river Arno as far as the city of Fucecchio.

- Pistoiese, spoken in the city of Pistoia and nearest zones (some linguists include this dialect in Fiorentino).

- Pesciatino or Valdinievolese, spoken in the Valdinievole zone, in the cities of Pescia and Montecatini Terme (some linguists include this dialect in Lucchese).

- Lucchese, spoken in Lucca and nearby hills (Lucchesia).

- Versiliese, spoken in the historical area of Versilia.

- Viareggino, spoken in Viareggio and vicinity.

- Pisano-Livornese, spoken in Pisa and in Livorno and the vicinity, and along the southern coast as far as the city of Piombino.

The Southern Tuscan dialects are (from east to west):

- Aretino-Chianaiolo, spoken in Arezzo and the Valdichiana.

- Senese, spoken in the city and province of Siena.

- Grossetano, spoken in the city and province of Grosseto.

Corsican and Gallurese:

- Corsican on the island of Corsica, and its variety spoken in Sardinia, are classified by scholars as a direct offshoot from medieval Tuscan.[6]

Speakers

Excluding the inhabitants of Province of Massa and Carrara, who speak an Emilian variety of a Gallo-Italic language, around 3,500,000 people speak the Tuscan dialect.

Dialectal features

The Tuscan dialect as a whole has certain defining features, with subdialects that are distinguished by minor details.

Phonetics

Tuscan gorgia

The Tuscan gorgia affects the voiceless stop consonants /k/ /t/ and /p/. They are often pronounced as fricatives in post-vocalic position when not blocked by the competing phenomenon of syntactic gemination:

- /k/ → [h]

- /t/ → [θ]

- /p/ → [ɸ]

Weakening of G and C

A phonetic phenomenon is the intervocalic weakening of the Italian soft g, the voiced affricate /dʒ/ (g as in George) and soft c, the voiceless affricate /tʃ/ (ch as in church), known as attenuation, or, more commonly, as deaffrication.

Between vowels, the voiced post-alveolar affricate consonant is realized as voiced post-alveolar fricative (z of azure):

This phenomenon is very evident in daily speech (common also in Umbria and elsewhere in Central Italy): the phrase la gente, 'the people', in standard Italian is pronounced [la ˈdʒɛnte], but in Tuscan it is [la ˈʒɛnte].

Similarly, the voiceless post-alveolar affricate is pronounced as a voiceless post-alveolar fricative between two vowels:

The sequence /la ˈtʃena/ la cena, 'the dinner', in standard Italian is pronounced [la ˈtʃeːna], but in Tuscan it is [la ˈʃeːna]. As a result of this weakening rule, there are a few minimal pairs distinguished only by length of the voiceless fricative (e.g. [laʃeˈrɔ] lacerò 'it/he/she ripped' vs. [laʃʃeˈrɔ] lascerò 'I will leave/let').

Affrication of S

A less common phonetic phenomenon is the transformation of voiceless s or voiceless alveolar fricative /s/ into the voiceless alveolar affricate [ts] when preceded by /r/, /l/, or /n/.

For example, il sole (the sun), pronounced in standard Italian as [il ˈsoːle], would be in theory pronounced by a Tuscan speaker [il ˈtsoːle]. However, since assimilation of the final consonant of the article to the following consonant tends to occur in exactly such cases (see "Masculine definite articles" below) the actual pronunciation will be usually [i ssoːle]. Affrication of /s/ can more commonly be heard word-internally, as in falso (false) /ˈfalso/ → [ˈfaltso]. This is a common phenomenon in Central Italy, but it is not exclusive to that area; for example it also happens in Switzerland (Canton Ticino).

No dipththongization of /ɔ/

There are two Tuscan historical outcomes of Latin ŏ in stressed open syllables. Passing first through a stage [ɔ], the vowel then develops as a diphthong /wɔ/. This phenomenon never gained universal acceptance, however, so that while forms with the diphthong came to be accepted as standard Italian (e.g. fuoco, buono, nuovo), the monophthong remains in popular speech (foco, bono, novo).

Morphology

Accusative "te" for "tu"

A characteristic of Tuscan dialect is the use of the accusative pronoun te in emphatic clauses of the type "You! What are you doing here?".

- Standard Italian: tu lo farai, no? 'You'll do it, won't you?'

- Tuscan: Te lo farai, no?

- Standard Italian: tu, vieni qua! 'You', come here!'

- Tuscan: Te, vieni qua!

Double dative pronoun

A morphological phenomenon, cited also by Alessandro Manzoni in his masterpiece "I promessi sposi" (The Betrothed), is the doubling of the dative pronoun.

For the use of a personal pronoun as indirect object (to someone, to something), also called dative case, the standard Italian makes use of a construction preposition + pronoun a me (to me), or it makes use of a synthetic pronoun form, mi (to me). The Tuscan dialect makes use of both in the same sentence as a kind of intensification of the dative/indirect object:

- In Standard Italian: [a me piace] or [mi piace] (I like it [lit. "it pleases me"])

- In Tuscan: [a me mi piace] (I like it)

This usage is widespread throughout the central regions of Italy, not only in Tuscany, and until recently, it was considered redundant and erroneous by Italian purists. Nowadays it has become acceptable except in the most formal of speech styles. More on this issue (in Italian) can be found at Accademia della Crusca [7]

In some dialects the double accusative pronoun me mi vedi (lit: You see me me) can be heard, but it is considered an archaic form.

Masculine definite articles

The singular and plural masculine definite articles can both be realized phonetically as [i] in Florentine varieties of Tuscan, but are distinguished by their phonological effect on following consonants. The singular provokes lengthening of the following consonant: [i kkaːne] 'the dog', whereas the plural permits consonant weakening: [i haːni] 'the dogs'. As in Italian, masc. sing. lo occurs before consonants long by nature or not permitting /l/ in clusters is normal (lo zio 'the uncle', lo studente 'the student'), although forms such as i zio can be heard in rustic varieties.

Noi + impersonal Si

A morphological phenomenon found throughout Tuscany is the personal use of the particle identical to impersonal si (not to be confused with passive Si or the reflexive Si), as the first person plural. It is basically the same as the use of on in French.

It's possible to use the construction Si + Third person in singular, which can be joined by the first plural person pronoun Noi, because the particle "si" is no longer perceived as an independent particle, but as a piece of verbal conjugation.

- Standard Italian: [Andiamo a mangiare] (We're going to eat), [Noi andiamo là] (We go there)

- Tuscan: [Si va a mangià] (We're going to eat), [Noi si va là] (We go there)

The phenomenon is found in all verb tenses, including compound tenses. In these tenses, the use of si requires a form of essere (to be) as auxiliary verb. The verb must be one which usually requires avere as auxiliary (it is not possible in Tuscan to form an impersonal compound tense with a verb that requires essere); the past participle does not have to agree with the subject in gender and number:

- Italian: [Abbiamo mangiato al ristorante]

- Tuscan: [S'è mangiato al ristorante]

Usually Si becomes S' before è.

Fo (faccio) and vo (vado)

Another morphological phenomenon in the Tuscan dialect is what might appear to be shortening of first singular verb forms in the present tense of fare (to do, to make) and andare (to go).

- Fare: It. faccio Tusc. fo (I do, I make)

- Andare: It. vado Tusc. vo (I go)

These forms have two origins. Natural phonological change alone can account for loss of /d/ and reduction of /ao/ to /o/ in the case of /vado/ > */vao/ > /vo/. A case such as Latin: sapio > Italian so (I know), however, admits no such phonological account: the expected outcome of /sapio/ would be */sappjo/, with a normal lengthening of the consonant preceding yod.

What seems to have taken place is a realignment of the paradigm in accordance with the statistically minor but highly frequent paradigms of dare (give) and stare (be, stay). Thus so, sai, sa, sanno (all singulars and 3rd personal plural of 'know') come to fit the template of do, dai, dà, danno ('give'), sto, stai, sta, stanno ('be, stay'), and fo, fai, fa, fanno ('make, do') follows the same pattern. The form vo, while quite possibly a natural phonological development, seems to have been reinforced by analogy in this case.

Loss of infinitival "-re"

A phonological phenomenon that might appear to be a morphological one is the loss of the infinitival ending -re of verbs.

- andàre → andà

- pèrdere → pèrde

- finìre → finì

An important feature of this loss is that main stress does not shift to the new penultimate syllable, as phonological rules of Italian might suggest. Thus infinitive forms can come to coincide with various conjugated singulars: pèrde 'to lose', pèrde 's/he loses'; finì 'to finish', finì 's/he finished'. In practice this homophony seldom, if ever, causes confusion, as they usually appear in distinct syntactic contexts.

The fixed stress can be explained by supposing an intermediate form in -r (as in the Spanish verbal infinitive).

While the infinitive without -re is universal in some subtypes such as Pisano-Livornese, in the vicinity of Florence alternations are regular, so that the full infinitive (e.g. vedere 'to see') appears when followed by a pause, and the clipped form (vedé) is found when phrase internal. The consonant of enclitics is lengthened if preceded by stressed vowel (vedèllo 'to see it', portàcci 'to bring us'), but not when the preceding vowel of the infinitive is unstressed (lèggelo 'to read it', pèrdeti 'to lose you').

Lexicon

The biggest differences among dialects is in the lexicon, which also distinguishes the different subdialects. The Tuscan lexicon is almost entirely shared with standard Italian, but many words may be perceived as obsolete or literary by non-Tuscans. There are a number of strictly regional words and expressions too.

Characteristically Tuscan words:

- accomodare (which means "to arrange" in standard Italian) for riparare (to repair)

- bove (literary form in standard Italian) for bue (ox)

- cacio for formaggio (cheese)

- camiciola for canottiera (undervest)

- cannella for rubinetto (tap)

- cencio for straccio (rag, tatters)

- chetarsi (literary form in standard Italian) for fare silenzio (to be silent)

- codesto (literary form in standard Italian) is a pronoun which specifically identifies an object far from the speaker, but near the listener.

- costì or costà is a locative adverb which refers to a place far from the speaker, but near the listener. It relates to codesto as qui/qua relates to questo, and lì/là to quello

- desinare (literary form in standard Italian) for pranzare (to have lunch)

- ghiaccio for ghiacciato, freddo (frozen, cold)

- essi for sii (imperative tense of 'to be')

- furia (which means "fury" in standard Italian) for fretta (hurry)

- golpe for volpe (fox)

- garbare for piacere (to like) (but also piacere is widely used in Tuscany)

- gota (literary form in standard Italian) for guancia (cheek)

- ire for andare (to go) (only some forms as ito (gone))

- lapis for matita (pencil)

- punto for per nulla or niente affatto (not at all) in negative sentences

- sciocco (which means "silly" or "stupid" in standard Italian) for insipido (insipid)

- sistola for tubo da giardinaggio (garden hose)

- sortì for uscire (to exit)

- sudicio for spazzatura (garbage) as a noun and for sporco (dirty) as an adjective

- termosifone for calorifero (radiator)

See also

- Augusto Novelli, Italian playwright known for using the Tuscan dialect for 20th-century Florentine theater

- The Adventures of Pinocchio, written by Carlo Collodi in Italian but employing frequent Florentinisms

References

- ↑ http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/storia-della-lingua_(Enciclopedia-dell'Italiano)/

- ↑ "Ali, Linguistic atlas of Italy". Atlantelinguistico.it. Retrieved 2013-11-22.

- ↑ Linguistic cartography of Italy by Padova University Archived May 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Italian dialects by Pellegrini". Italica.rai.it. Retrieved 2013-11-22.

- ↑ AIS, Sprach- und Sachatlas Italiens und der Südschweiz, Zofingen 1928-1940

- ↑ Harris, Martin; Vincent, Nigel (1997). Romance Languages. London: Routlegde. ISBN 0-415-16417-6.

- ↑ "Risposte ai quesiti" (in Italian). Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- Giannelli, Luciano. 2000. Toscana. Profilo dei dialetti, 9. Pisa: Pacini.