Turkish Cypriot enclaves

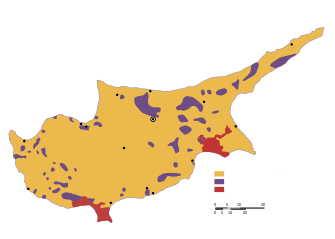

The Turkish Cypriot enclaves were enclaves inhabited by Turkish Cypriots between the intercommunal violence of 1963-64 known as Bloody Christmas and the 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus.

Events leading to the creation of the enclaves

In December 1963 the President of the Republic of Cyprus, Archbishop Makarios, proposed several controversial amendments to the constitution. This precipitated a major crisis between the Greek Cypriot and the Turkish Cypriot communities, and Turkish Cypriot representation in the government ended. The nature of this event is controversial; Greek Cypriots prevented some Turkish Cypriots from entering government institutions, but Turkish Cypriot leadership called upon some Turkish Cypriots to withdraw.[1]

After the rejection of the constitutional amendments by the Turkish Cypriot community the situation escalated into island-wide intercommunal violence. 103 to 109 Turkish Cypriot or mixed villages were attacked and 25,000-30,000 Turkish Cypriots became refugees.[2][3] According to official records, 364 Turkish Cypriots and 174 Greek Cypriots were killed.[4] Turkish Cypriots consequently started living in enclaves; the republic's structure was changed unilaterally by Makarios and Nicosia was divided by the Green Line, with the deployment of UNFICYP troops.[3]

Situation in the enclaves

The enclaves were scattered all over the island. The enclaves were deprived of many necessities. Restrictions on the enclaves began to be eased after 1967 and many Turkish Cypriots began to return to the villages they'd left in 1963.

Ban on goods

The Greek Cypriot-run Republic of Cyprus banned the possession of certain items by Turkish Cypriots and the entrance of these items to the enclaves. The restrictions were aimed not only at restricting the military activities of Turkish Cypriots, but also to prevent their return to economic normality. As for fuels, all kinds of fuels including kerosene were initially banned, but the ban on kerosene was lifted by October 1964. The ban on petrol and diesel did remain in force until that time and hindered food supply to the enclaves. Ban on building materials prevented the restoration of houses damaged by fighting when winter approached, and the ban on woolen clothing affected the supply of clothing to Turkish Cypriots, especially putting the displaced in a concerning situation. The restriction on tent materials further blocked the construction of temporary places of residence for the displaced. Below is a list of banned items as of 7 October 1964, according to a report by the United Nations Secretary-General:[5]

|

|

|

Travel restrictions

The freedom of movement of Turkish Cypriots were restricted in this period. The Greek Cypriot police committed what was called by the UN Secretary-General "excessive checks and searches and apparently unnecessary obstructions", which instilled fear in Turkish Cypriots who had to travel.[5] Turkish Cypriots suffered the harassment of nationalist Greek Cypriot officers at control points, airports and government offices.[6] The Secretary-General also noted his concerns about arbitrary arrest and detention. Greek Cypriot police imposed restrictions on Turkish Cypriot travel outside the enclave of North Nicosia. Initially, the movement of Turkish Cypriots in and out of Lefka was not allowed at all, the restriction was relaxed by October 1964 to allow them to travel eastwards, but not westwards towards Limnitis. Turkish Cypriot doctors were also not allowed to travel freely to carry out their profession, the Greek Cypriots insisted that they should be searched.[5]

Economic situation

The period of 1963-74 saw widening economic disparities between the two communities. Whilst the Greek Cypriot economy benefited from flourishing tourism and finance sectors, Turkish Cypriots grew increasingly poor and unemployment increased.[7] The enclaves were put under an economic embargo by the Greek Cypriot administration of the Republic of Cyprus, trade between communities was blocked. Due to travel restrictions, a large number of Turkish Cypriots had to leave their previous jobs. Refugees, meanwhile, had been uprooted from their old sources of income. The period thus saw the beginning of aid from the Turkish government, as by 1968, Turkey had started to give about £8,000,000 a year to Turkish Cypriots.[8]

After the Turkish invasion in 1974

After the 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus the island was divided in two. A year later in 1975 60,000 Turkish Cypriots, practically all of the Turkish Cypriot community in the Greek Cypriot controlled south, moved to the occupied territories in the north.[9] In 1983 the northern part declared its independence and became the internationally unrecognized (except by Turkey) Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.

List of Turkish Cypriot enclaves

- Kokkina (Erenköy)

- Limnitis (Yeşilırmak)

- Lefka (Lefke)

- Lefkosia-Agyrta (Lefkoşa-Ağırdağ)

- Tsatos (Tziaos/Serdarlı)

- Galinoporni (Kuruova)

- Kophinou (Geçitkale)

- Lourojina (Akincilar)

- Gaziveren - Angolemi

Smaller enclaves within the main cities

- Pafos (Mouttalos/Kasaba)

- Larnaka (İskele)

- Famagusta (Mağusa/Suriçi)

References

- ↑ Ker-Lindsay, James (2011). The Cyprus Problem: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford University Press. pp. 35–6. ISBN 9780199757169.

- ↑ John Terence O'Neill, Nicholas Rees. United Nations peacekeeping in the post-Cold War era, p.81

- 1 2 Hoffmeister, Frank (2006). Legal aspects of the Cyprus problem: Annan Plan and EU accession. EMartinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 17–20. ISBN 978-90-04-15223-6.

- ↑ Oberling, Pierre. The road to Bellapais (1982), Social Science Monographs, p.120: "According to official records, 364 Turkish Cypriots and 174 Greek Cypriots were killed during the 1963-1964 crisis."

- 1 2 3 "REPORT BY THE SECRETARY-GENERAL ON THE UNITED NATIONS OPERATION IN CYPRUS (For the period 10 September to 12 December 1964) - Annex II. Doc S/6103" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ↑ Asmussen, Jan (2014). "Escaping the Tyranny of History". In Ker-Lindsay, James. Resolving Cyprus: New Approaches to Conflict Resolution. I.B.Tauris. p. 35. ISBN 9781784530006.

- ↑ Ker-Lindsay, James, ed. (2014). Resolving Cyprus: New Approaches to Conflict Resolution. I.B.Tauris. p. 35. ISBN 0857736019.

- ↑ Navaro-Yashin, Yael (2012). The Make-Believe Space: Affective Geography in a Postwar Polity. Duke University Press. p. 87. ISBN 0822352044.

- ↑ “1974: Turkey Invades Cyprus” BBC 2010. Web. Retrieved: 2 October 2010. <http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/july/20/newsid_3866000/3866521.stm>