Tumbler Ridge

| Tumbler Ridge | ||

|---|---|---|

| District municipality | ||

| District of Tumbler Ridge[1] | ||

| ||

| Motto: "Invitatio Prosperitati" | ||

| ||

| Coordinates: 55°06.7′N 120°58.2′W / 55.1117°N 120.9700°WCoordinates: 55°06.7′N 120°58.2′W / 55.1117°N 120.9700°W | ||

| Country | Canada | |

| Province | British Columbia | |

| Regional District | Peace River | |

| Incorporated | April 9, 1981 (district) | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Don Mcpherson | |

| • Governing body | Tumbler Ridge District Council | |

| • MP | Bob Zimmer | |

| • MLA | Mike Bernier | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 1,558.97 km2 (601.92 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 830 m (2,720 ft) | |

| Population (2011) | ||

| • Total | 2,710 | |

| • Density | 1.7/km2 (4.5/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | Mountain Time Zone (UTC-7) | |

| • Summer (DST) | not observed (UTC-7) | |

| Postal code span | V0C 2W0 | |

| Area code(s) | 250 / 778 / 236 | |

| Highways |

| |

| Website | District of Tumbler Ridge | |

Tumbler Ridge is a district municipality in the foothills of the Canadian Rockies in northeastern British Columbia, Canada, and a member municipality of the Peace River Regional District. The municipality of 1,558 square kilometres (602 sq mi), with its population of 2,710 people, incorporates a townsite and a large area of mostly Crown Land.[2] The housing and municipal infrastructure, along with regional infrastructure connecting the new town to other municipalities, were built simultaneously in 1981 by the provincial government to service the coal industry as part of the British Columbia Resources Investment Corporation's Northeast Coal Development.

In 1981, a consortium of Japanese steel mills agreed to purchase 100 million tonnes of coal over 15 years for US$7.5 billion from two mining companies, Denison Mines Inc. and the Teck Corporation, who were to operate the Quintette mine and the Bullmoose mine respectively. Declining global coal prices after 1981, and weakening Asian markets in the late 1990s, made the town's future uncertain and kept it from achieving its projected population of 10,000 people. The uncertainty dissuaded investment and kept the economy from diversifying. When price reductions were forced onto the mines, the Quintette mine was closed in 2000 production and the town lost about half its population. Coal prices began to rise after the turn of the century, leading to the opening of the Peace River Coal Trend mine by Northern Energy & Mining Inc. (now owned by Anglo American Met Coal) and the Wolverine Mine, originally owned by Western Canadian Coal, which was purchased by Walter Energy in 2010.[3]

After dinosaur footprints, fossils, and bones were discovered in the municipality, along with fossils of Triassic fishes and cretaceous plants, the Peace Region Paleontology Research Center opened in 2003. The research centre and a dinosaur museum were funded in part by the federal Western Economic Diversification Canada to decrease economic dependence on the coal industry.

In 2014, both operating coal mines were put into "care and maintenance mode". This means the mines are effectively closed, but are still allowed to restart without needing to go through the process of getting a new mines act permit.

Economic diversification has also occurred with oil and gas exploration, forestry, and recreational tourism. Nearby recreational destinations include numerous trails, mountains, waterfalls, snowmobiling areas and provincial parks, such as Monkman Provincial Park, Bearhole Lake Provincial Park, and Gwillim Lake Provincial Park.

History

Archaeological evidence show a human presence dating back 3,000 years.[4] The nomadic Sekani, followed by the Dunneza and then the Cree, periodically lived in temporary settlements around the future municipality.[5] Formal exploratory and surveying expeditions were conducted by S. Prescott Fay, with Robert Cross and Fred Brewster in 1914, J.C. Gwillim in 1919, Edmund Spieker in 1920, and John Holzworth in 1923. Spieker coined the name Tumbler Ridge, referring to the mountains northwest of the future town, by altering Gwillim's map that named them Tumbler Range.[6] Permanent settlers were squatters, five families by 1920, who maintained trap lines. In the 1950s and 1960s, oil and natural gas exploration and logging was conducted through the area, and 15 significant coal deposits were discovered.[7] Coal prices rose after the 1973 oil crisis leading to 40 government studies examining the viability of accessing the coal, given the 1,130 km (700 mi) to the nearest port and the mountainous barrier.[8]

With these coal deposits in mind, a purchasing agreement was signed in 1981 by two Canadian mining companies, a consortium of Japanese steel mills, and the governments of British Columbia and Canada. As part of the deal, the provincial government committed, under the North East Coal Development plan, to build a new town near the deposits, two highways off Highway 97, a power line from the W. A. C. Bennett Dam at Hudson's Hope, and a branch rail line through the Rocky Mountains. An alternative of using work camps staffed by people from Dawson Creek and Chetwynd was also considered. Massive initial investments were required as planning for the new town began in 1976 with the objective of having a fully functioning town ready before residents arrived.[9] Coordinated through the provincial Ministry of Municipal Affairs the town, regional infrastructure, and mining plants were all built simultaneously. When the municipality was incorporated in April 1981 the area was completely forested.[10] During that year building sites and roadways were cleared[10] and in the winter the water and sewerage system was built. In 1982, houses and other buildings were constructed. Full production at the mines was reached the following year.

In early 1983, the families of the managers at the Bullmoose Minesite, led by Dean Sawas appealed to the British Columbia government and were able to create a new settlement, called Bullmoose Settlement. This was done because Dean's wife was expecting and he wanted his child to have something different to say about her birthplace. He wanted her to be able to say that a settlement had been created for her and that she was, and would always be the only one born at that place. At her birth, Alicia V. Sawas was also written into the Tumbler Ridge records as the first child born in the Quintette area. Bullmoose Settlement was closed down after the reduction in mine activities with just the one birth.

In 1984, world coal prices were dropping and the Japanese consortium requested a reduction in the price of coal from the Tumbler Ridge mines. As price reduction requests continued, the concern over the viability of the mines led the BC Assessment Authority to lower the 1987 property assessments for the Quintette mine from CAD$156 million to $89 million and the Bullmoose mine $70 million to $43 million.[11] This lowered their taxes as they tried to enforce the purchasing agreement at the Supreme Court of Canada. Their 1990 ruling required the Quintette Operations Company to reduce coal prices and reimburse the Japanese consortium $4.6 million. The company responded by reducing production, cutting employment, and applying for court protection from creditors. This allowed Teck to acquire 50% interest and take over management of the Quintette mine, but it was unable to stop further job losses.[12] As most residents left town, apartment blocks were closed and the mine companies bought back all but 11 houses in the town. After 30% of the workforce had been laid off, new contracts with the Japanese consortium were signed in 1997, allowing re-hirings to begin, but with lower export levels.[11] The North East Coal Development was projected to create a net benefit of CAD$0.9 billion (2000), but incurred a net loss of $2.8 billion and half the expected regional employment.[13]

The population declined as many residents were unable to find other work in the town, even as a sawmill for specialty woods opened in 1999. After Teck closed the Quintette mine in August 2000 and shifted production to the lower cost Bullmoose mine, the town council established the Tumbler Ridge Revitalization Task Force to investigate ways to boost and diversify the economy. The Task Force negotiated the return of the housing stock from the mines to the free market, grants from the province to become debt-free,[14] and stabilized funds from the province for healthcare and education.[15] The discovery of dinosaur tracks in 2000 by two local boys while playing near a creek, led to major fossil and bone discoveries from the Cretaceous Period. To survey and study the finds, government funding was secured to found both the Tumbler Ridge Museum Foundation and Peace Region Palaeontology Research Centre.

After the Bullmoose mine exhausted its supply of coal in 2003, world coal prices increased, making exploration and mining in Tumbler Ridge economically feasible again. Western Canadian Coal opened new open-pit mining operations creating the Dillon mine using Bullmoose mining infrastructure, the Brule mine near Chetwynd using new infrastructure (projected 11-year life span),[16][17] and the Wolverine mine.[18] These mines were purchased by Walter Energy in 2010, but world coal prices began to drop again in 2011, and in April 2014, Walter put their Canadian operations into "care and maintenance mode", laying off nearly 700 people.[19]

The Peace River Coal Trend Mine was issued its mines act permit in 2005, and was a partnership between NEMI Northern Energy and Mining Inc., Anglo American, Hillsborough Resources and Vitol Anker International. In 2011, Anglo American bought out the rest of the partners to become sole owner of the property.[20]

Anglo American started working on the Roman Pit next to their existing Trend operation in 2014, hoping to reduce the cost of production per tonne of coal. However, in late 2014, they announced the mine would be going into care and maintenance mode as well.[21]

As of Fall, 2015, there are no coal mines operating in Tumbler Ridge. However, HD Mining is continuing work on the Murray River Coal Mine, a proposed Underground Longwall Mine near Tumbler Ridge. The company was issued its Environmental Assessment Certificate from the BC Government in October 2015, though construction on the mine, if it were to go ahead, is not expected to begin until after a Mines Act Permit is issued, which is not expected until late 2016.

On September 22, 2014, the area around Tumbler Ridge was designated North America's second Geopark.[22]

Demographics

Population projections in 1977 were for 3,568 residents in 1981, 7,940 in 1985, and 10,584 in 1987, after which the level was expected to stabilize.[26] However, requests for lower coal prices shortly after the production began placed a persistent insecurity over the viability of the mines, and therefore the town, discouraging long term investments. Temporary work camps, where workers numbered between 200 and 2,000, were used during the construction of the town and mines. The planners of the town advised the mining companies to hire workers who were married, believing they would live in Tumbler Ridge longer and reduce employment turn-over.[27] The population rose slowly to 3,833 people in 1984, nearly half the projected level.[28] The 1986 Canadian census, the first census to include Tumbler Ridge, recorded 4,566 residents after which in-migration ended and the population level began to fluctuate.[24] The population peaked in 1991 at 4,794 people but then declined to a low of 1,932 people in 2001.[24][25] Since then, population growth has been led by new mining activities and increased exploration following higher world energy prices. The town's population is currently in a state of flux as people dependent on the mines for work leave, while other people, attracted by the town's low rent, arrive.

| Canada 2006 Census[29][30] | ||

| Tumbler Ridge | British Columbia | |

| Median age | 42.2 years | 40.8 years |

| Under 15 years old | 18% | 17% |

| Over 65 years old | 11% | 15% |

| Protestant (2001) | 43% | 31% |

| Catholic (2001) | 29% | 17% |

The Canada 2006 Census reported 2,454 residents living in 1,045 households and 765 families.[30] This was 27% more people than the previous census five years earlier when the town was at its lowest population level since opening. The median age increased from 38.8 years in 2001 to 42.2 in 2006, as the proportion of the population aged over 65 rose from 5% to 11%. In 2006, of those over 15 years of age, 62% were married, higher than the 54% provincial average. The town has few visible minorities as 94% of Tumbler Ridge residents were Canadian-born and 93% had English as their first language.[30] Though not included as a minority, 9% of residents claimed to have an Aboriginal identity.[30] Reflecting the nature of the industrial jobs available in town, in 2001, only 12% of residents between 20 and 64 years of age completed university, half of the provincial average, and 26% did not complete high school, much higher than the 19% provincial average.[29]

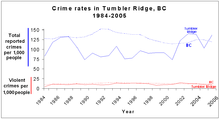

In 2005, the five officer Tumbler Ridge Royal Canadian Mounted Police municipal detachment reported 346 Criminal Code offences. This translated into a crime rate of 137 Criminal Code offences per 1,000 people, higher than the provincial average of 119 offences. During that year, the RCMP reported lower crime rates in Tumbler Ridge, compared with the provincial averages, in all categories except bicycle thefts, property damage, impaired driving, and cannabis-related offences. Until 2005, the town had a lower crime rate than the province, except between 2001 and 2003 after the Quintette mine closure and a large out-migration from the town. In 2004 the Tumbler Ridge RCMP reported no robbery or shoplifting offences, and only 4.5 theft-from-motor-vehicle offences per 1,000 people compared with 20 provincially.[31]

Geography and climate

The townsite is located on a series of southern-facing gravel terraces on a ridge of Mount Bergeron, overlooking the confluence of the Murray and Wolverine Rivers.[32] The site, above the floodplain of the Murray River, has well-drained soils with easy access to aquifers with potable water.[33] The rocks, mostly shale and mudstone but lacking quartzite, make the mountains less rugged than their neighbouring ranges.[34] The terraces grow Lodgepole Pine, White Spruce, Trembling Aspen trees. Moose and elk are common.[35][36] Escarpments to the east and north could pose a snow avalanche threat but are kept forested for stability.[37] In 2006, the town was evacuated for several days as four forest fires approached the town.[38]

Major coal deposits indicate the site was a swampy forest during the Cretaceous.[39] Paleontologists have discovered tracks or fossils from ankylosauria, ornithopods (including a Hadrosaurus), and theropods.[40] Fossils of Cretaceous plants such as ferns, redwoods, cycads, and ginkgo, and Triassic fishes and reptiles such as coelacanth, weigeltisaurus, and ichthyosaur have been recovered.[41]

The town experiences a continental climate. Arctic air masses move predominantly southwestly from the Mackenzie Valley towards the Rocky Mountains and through the mountains north of town.[42] The town is in a rain shadow behind Mount Bergeron, though much of the precipitation is lost in the mountains beforehand. Town planners laid out the roads so that they run along wind breaks, and buildings and parks are located in wind shadows.[43]

| Weather[44][45] | ||

| Time | Average temperature | Average precipitation |

| January | −11.1 °C (12.0 °F) | 40.2 mm (1.6 in) |

| July | 14.8 °C (58.6 °F) | 78.6 mm (3.1 in) |

| Average annual precipitation : 519 mm (20.4 in) | ||

After examining other resource towns in Canada, the planners followed socio-spatial guidelines and principles in physical planning.[46] The coal mining facilities were well separated from the townsite to minimize the feeling of a company town.[11] An attempt to mitigate potential lifestyle conflicts between families and childless households was made by separating the low-density, single-family dwellings from the low-rise apartments.[47] The apartment blocks were planned for areas with clusters of trees and excellent viewscapes, but close to the town plaza.[48] The low-density residences that were more likely to have children living in them were oriented around elementary schools and parks. Cul-de-sacs were avoided in favour of better linkages and pedestrian access.[47]

| Climate data for Tumbler Ridge | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16 (61) |

16 (61) |

21.5 (70.7) |

26 (79) |

30 (86) |

33 (91) |

34 (93) |

35.5 (95.9) |

35 (95) |

26.5 (79.7) |

18 (64) |

14 (57) |

35.5 (95.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −4.5 (23.9) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

3.5 (38.3) |

10.6 (51.1) |

16.1 (61) |

20 (68) |

22.4 (72.3) |

21.9 (71.4) |

17.1 (62.8) |

9.7 (49.5) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−2.2 (28) |

9.5 (49.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −9.7 (14.5) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

3.9 (39) |

9 (48) |

13.1 (55.6) |

15.1 (59.2) |

14.5 (58.1) |

10.3 (50.5) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−4 (25) |

−7 (19) |

3.4 (38.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −14.8 (5.4) |

−12.8 (9) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

1.9 (35.4) |

6.2 (43.2) |

7.9 (46.2) |

7.1 (44.8) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−2.8 (27) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −46 (−51) |

−39.5 (−39.1) |

−37 (−35) |

−24 (−11) |

−10 (14) |

−2 (28) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−4 (25) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−23.5 (−10.3) |

−41.5 (−42.7) |

−42 (−44) |

−46 (−51) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 40.8 (1.606) |

24.9 (0.98) |

36 (1.42) |

22 (0.87) |

30.4 (1.197) |

78.5 (3.091) |

77.7 (3.059) |

56.3 (2.217) |

39.8 (1.567) |

27.8 (1.094) |

43.4 (1.709) |

24.6 (0.969) |

502.3 (19.776) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 2.4 (0.094) |

1.4 (0.055) |

3.1 (0.122) |

13.2 (0.52) |

26.9 (1.059) |

78.5 (3.091) |

77.7 (3.059) |

56 (2.2) |

37.9 (1.492) |

14 (0.55) |

7.1 (0.28) |

3.5 (0.138) |

321.5 (12.657) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 38.4 (15.12) |

23.5 (9.25) |

33 (13) |

8.8 (3.46) |

3.6 (1.42) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.4 (0.16) |

1.9 (0.75) |

13.8 (5.43) |

36.3 (14.29) |

21.1 (8.31) |

180.9 (71.22) |

| Source: [49] | |||||||||||||

Infrastructure

Two highways diverge from Highway 97 and intersect in Tumbler Ridge: Highway 52 (Heritage Highway) which runs 98 km (61 mi) south at Arras, and Highway 29 which runs 90 km (56 mi) southeast from Chetwynd. At the intersection Highway 29 ends but Highway 52 continues south through Tumbler Ridge, then unpaved, it runs northeast to Highway 2 near the Alberta border. In town, the 28 km (17 mi) of paved roads[50] are laid out in a curvilinear pattern that use two arterial roads, MacKenzie Way and Monkman Way, to connect each section of town. Service roads from the townsite to the mines and forestry areas are maintained by the industries but are unpaved.

The unmanned Tumbler Ridge Airport, with its 1,219 m (4,000 ft) asphalt runway, is used by chartered and local flights. The closest airports with regularly scheduled flights are in Dawson Creek, Fort St John and Grande Prairie.[51] The rail line into town is a 132 km (82 mi) formerly electrified branch line through the Rocky Mountains constructed by BC Rail to transport coal to the Ridley Terminal at the Port of Prince Rupert. The branch line includes two major tunnels: the 9 km (6 mi) Table Tunnel and the 6 km (4 mi) Wolverine Tunnel.

The town funds its own 21-member volunteer fire department, water treatment system, and sewage disposal system. Drinking water is drawn from two springs south of the townsite where it is stored in a 7 million litre reservoir before being chlorinated and pumped into town. The storm sewers empty into the Murray River, but the sanitary sewage is processed through a lagoon system and released into the Murray River north of town.[33] Both the town and the province, through the Northern Health Authority, operate the Tumbler Ridge Community Health Centre. The closest hospitals with over-night beds are in Chetwynd and Dawson Creek. The two public schools, Tumbler Ridge Elementary School and Tumbler Ridge Secondary School are run by the School District 59 Peace River South. Post-secondary courses, programs, and industry training are offered by Northern Lights College at the secondary school and community centre.

Economy

Tumbler Ridge was built to provide a labour force for the coal mining industry, which has remained the dominant employer throughout the town's history. The mining companies had a contract to sell 100 million tons of coal to a consortium of Japanese steel mills over 15 years for US$7.5 billion (1981). The Quintette Operating Corporation (QOC) was formed by partnership between Denison Mines (50%), Mitsui Mining (20%), Tokyo Boeki (20%), and other smaller firms, and began blasting at the Quintette mine in October 1982. The Bullmoose Operating Corporation was formed by the Teck Corporation (51%), Lornex (39%), Nissho Iwai (10%) and worked the smaller Bullmoose mine. The economic viability of the mining companies were in question since the world coal prices began falling in the early 1980s and the Japanese consortium requested reduced prices. After the Supreme Court ruled that the coal prices must be reduced, the QOC filed for court protection from its creditors allowing the Teck Corporation to take over management in 1992. By 1996, even as lay-offs continued, over half the town's labour force were employed at one of the two mines.[52] New contracts with the Japanese consortium, signed 1997, moved production to the lower cost Bullmoose mine but guaranteed production until 2003 when that mine was expected to be exhausted. The Quintette mine was closed altogether on August 31, 2000.

While there was an intent by the town's planners to move to a more diversified economy, the few initiatives in this direction were not supported by the industries or local decision-makers.[53] Uncertainty about the town's future had been a serious concern to residents since the 1984 price reduction demands, but it was not until the closure of the Quintette mine that the town seriously investigate a diversification. Since then employment has been generated in tourism (attractions from dinosaur fossil discoveries, outdoor recreation, and nearby provincial parks), forestry, and oil and gas exploration.

A $1.4 billion Murray River coal mine project near Tumbler Ridge, operated by HD Mining International, a company majority-owned by Huiyong Holdings Group, a private company from China uses long-wall mining in which "coal is extracted along a wall in large blocks and then carried out on a conveyor belt." [54] Penggui Yan, CEO of HD Mining and its controlling shareholder, was a manager [55] of the state-owned China Shenhua Energy Co (CSEC), China's largest coal company, which had developed a highly advanced long-wall mining technology.[56][56] In 2013 HD mining brought in 52 workers from China through the federal Temporary Foreign Worker Program(TFWP) claiming a requirement of the job is an ability to speak Mandarin.[54][57][58] The hiring was challenged in a Vancouver federal court by two labour unions in April 2013,[59][60][61] The unions claimed there were qualified Canadian job applicants, however the case was dismissed by Justice Russell Zinn who found there was nothing to support the unions claim.[62][63][64][65]

Culture, recreation and media

After dinosaur trackways were discovered in 2000, and bones in 2002, the Tumbler Ridge Museum Foundation began excavations and opened the Peace Region Palaeontology Research Centre.[66] Fossils and bones are displayed at both locations. Tours and educational programs related to dinosaur, the trackways, and the wilderness are offered.[67]

Tumbler Ridge's location among the Rocky Mountains has allowed for the development of numerous trail systems for motorized and non-motorized recreation. The trails and open areas span numerous mountains. Kinuseo Falls along the Murray River in the Monkman Provincial Park is the most popular destination for visitors to Tumbler Ridge.[68] Two other provincial parks are just outside the municipal boundaries: Bearhole Lake Provincial Park and Gwillim Lake Provincial Park.

Annual events held in Tumbler Ridge include the Grizfest Music Festival, Emperor's Challenge – promoted as the most beautiful and most challenging half-marathon in the world – and the Ridge Ramble Cross-Country Ski Race. The Grizfest Music Festival (formerly Grizzly Valley Days) is a two-day concert held on the August long weekend, and includes a parade, dance, art show, and other community-wide events.[69] The Emperor's Challenge, also in August, is a 21 km (13 mi) marathon up Roman Mountain.[70]

Tumbler Ridge has one newspaper published in the community, the locally owned and operated Tumbler Ridge News (formerly Community Connections). The Tumbler Ridge Observer formerly covered the town and was published by the Peace River Block Daily News in Dawson Creek. The Ridge Blog was a short-lived online news source. One newsletter, Coffee Talk, based out of Chetwynd, is circulated in the town. No radio station, or television station broadcasts from the town but there are local repeaters for stations from larger centres.

In Fall 2014 Tumbler Ridge was designated a full member of UNESCO's Global Geopark Network being only the second Geopark in North America and the first in the West. The Tumbler Ridge Geopark Committee is dedicated to developing tourism and business in the area.

Government and politics

The District of Tumbler Ridge's council-manager form of municipal government is headed by a mayor (who also represents Tumbler Ridge on the Peace River Regional District's governing board) and a six-member council; these positions are subject to at-large elections every three years. Don McPherson was elected mayor on November 15, 2014, succeeding Darwin Wren. Sherry Berringer was elected as school trustee for a third term, sitting on the board of School District 59.[71] The city funds a volunteer fire department headed by full-time fire chief Matt Treit.

Tumbler Ridge is part of the Peace River South provincial electoral district, represented, since 2013, by Mike Bernier in the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia. Prior to Bernier, the riding was represented by Blair Lekstrom who was elected in the 2001 provincial election, with 72% support from the town's polls[72] and re-elected in 2005 with 64%[73] and in 2009 with 70% support.[74] Before Lekstrom, Peace River South was represented by Jack Weisgerber as a member of the Social Credit Party of British Columbia (1986–1994) and Reform Party of British Columbia (1994–2001). In 1996, as leader of the Reform Party, Weisgerber won re-election despite the Tumbler Ridge polls placing him second to the New Democratic Party candidate.[75]

Federally, Tumbler Ridge is in the Prince George—Peace River riding, represented in the Canadian House of Commons by Conservative Party Member of Parliament Bob Zimmer. Before Zimmer, who was elected in May 2011, the riding was represented by Jay Hill since 1993. The riding was represented by Frank Oberle of the Progressive Conservative Party from 1972 to 1993. Oberle served as Canada's Minister of Science and Technology in 1985 and Minister of Forestry in 1989.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ "British Columbia Regional Districts, Municipalities, Corporate Name, Date of Incorporation and Postal Address" (XLS). British Columbia Ministry of Communities, Sport and Cultural Development. Archived from the original on July 13, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ↑ BC Stats, Community Facts, 2006.

- ↑ Crust, Julie. "Walter Energy seals $3.3 billion Western Coal buy". Reuters. Reuters. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ Helm (2001), 67

- ↑ Helm (2001), 68–69

- ↑ Helm (2000), 45.

- ↑ Helm (2000), 49, 76.

- ↑ Helm (2000), 76.

- ↑ Halseth (2002), 38–39.

- 1 2 "Tumbler Ridge looks ready for the builders", Alaska Highway News, December 30, 1981.

- 1 2 3 Halseth (2002).

- ↑ "More layoffs in northeast B.C.", CBC News, June 24, 1999.

- ↑ Gunton, 505.

- ↑ "Tumbler Ridge gets $6-million bail out", CBC News, October 27, 2000.

- ↑ Halseth (2002), 182, 192.

- ↑ Ministry of Environment, July 6, 2006.

- ↑ Environmental Assessment Office, June 9, 2006.

- ↑ Western Canadian Coal, October 2003.

- ↑ Carter, Mike. "Temporary layoffs for 415 people at Wolverine and 280 employees at Brazion effective immediately.". Tumbler Ridge News. Tumbler Ridge News, Ltd. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ Andrew, Topf. "Anglo American buys rest of Peace River Coal for $166m". Mining.com. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ Ernst, Trent. "PRC winding down by end of year". Tumbler Ridge News.

- ↑ Ernst, Trent. "The Best Thing to Happen to Tumbler Ridge Since Coal". Tumbler Ridge News. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ 1984 & 1985 figures from Halseth (2002), 86.

- 1 2 3 BC Stats, Municipal Census Populations, 1986–1996.

- 1 2 BC Stats, Municipal Census Populations, 1996–2006.

- ↑ Thompson et al. (1978), 25.

- ↑ Thompson et al. (1978), 32

- ↑ Halseth (2002), 86.

- 1 2 Statistics Canada, 2001 Community Profiles.

- 1 2 3 4 Statistics Canada, 2006 Community Profiles.

- 1 2 Police Services Division, pp. 101, 106–110, 151, 154.

- ↑ Thompson et al. (1978), 85.

- 1 2 PLEDA, 76.

- ↑ Helm (2000), 6.

- ↑ Thompson et al. (1978), 86–87.

- ↑ Helm (2001), 349.

- ↑ Thompson et al. (1978), 86.

- ↑ "More layoffs in northeast B.C." CBC News, July 4, 2006.

- ↑ Helm (2000), 5.

- ↑ Helm (2001), 57–61.

- ↑ Helm (2001), 53–55, 61–63.

- ↑ Thompson et al. (1978) 88–89.

- ↑ Thompson et al. (1978), 95.

- ↑ Fern Duperreault, Environment Canada, as cited in Helm (2001), 9.

- ↑ Tumbler Ridge (2004), 6.

- ↑ Thompson et al. (1978), 97.

- 1 2 Thompson et al. (1978), 99.

- ↑ Thompson et al. (1978), 97, 99.

- ↑ "Calculation Information for 1981 to 2010 Canadian Normals Data". Environment Canada. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ↑ Reed Construction, 23.

- ↑ Tumbler Ridge (2006), Flying to Tumbler Ridge.

- ↑ Halseth (2002), 111.

- ↑ Halseth (2003), 145.

- 1 2 "B.C. mine's temporary foreign workers case in Federal Court: Unions challenge hiring of Chinese workers for B.C. coal mine". CBC News. 9 April 2013.

- ↑ Stueck, Wendy (18 February 2013). "Initial pitch for Murray River did not use longwall mining". Vancouver, BC: The Globe and Mail.

- 1 2 International Mining (PDF) (Report). Infomine. 2007.

- ↑ "Fact Sheet — Temporary Foreign Worker Program". Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Citizenship and Immigration Canada.

- ↑ Diana Mehta (July 5, 2013) "Temporary Foreign Worker Program May Be Distorting Labour Market Needs: Study", Huffington Post

- ↑ "B.C. Mine's Temporary Foreign Workers Case In Federal Court", April 9, 2013, Huffington Post

- ↑ "Decision looms in case of Chinese workers at B.C. coal mine". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. 2013-04-08.

- ↑ "Harper says foreign worker program is being fixed". CBC News. May 7, 2013.

- ↑ "Temporary foreign worker case involving B.C. coal mine dismissed". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. 2013-05-22.

- ↑ "B.C. mine's temporary foreign workers case dismissed". CBC News. May 21, 2013.

- ↑ Jeremy Nuttall (May 21, 2013) "Judge dismisses HD Mining court challenge by unions", canoe.ca

- ↑ Thomas Walkom (May 22, 2013). "Stephen Harper keeps his distance from distracting Senate scandal, focuses on the economy". The Star. Toronto.

- ↑ McCrea (2003).

- ↑ Tumbler Ridge Museum (2008).

- ↑ Helm (2001), 261.

- ↑ Grizfest, 2007.

- ↑ Emperor's Challenge, 2007.

- ↑ School District 59 (2005).

- ↑ Elections BC (2001).

- 1 2 Elections BC (2005).

- ↑ Elections BC (2009).

- ↑ Elections BC (1996).

- ↑ Elections Canada (2011).

References

- BC Stats. "British Columbia Municipal Census Populations, 1986–1996". British Columbia. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- BC Stats. "British Columbia Municipal Census Populations, 1996–2006". British Columbia. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- BC Stats (September 8, 2006). "Tumbler Ridge District Municipality" (PDF). Community Facts. British Columbia. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- Dawson Creek & District Chamber of Commerce. "A Socio-economic profile of the South Peace River Region, British Columbia, Canada" (PDF). 2003 Edition. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- Elections BC (2001). "Peace River South Electoral District" (PDF). Statement of Votes, 2001. British Columbia. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- Elections BC (2005). "Peace River South Electoral District" (PDF). Statement of Votes, 2005. British Columbia. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- Elections BC (1996). "Peace River South Electoral District" (PDF). 36th Provincial General Election - May 28, 1996. British Columbia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- Elections Canada (2006). "Prince George—Peace River". Thirty-ninth General Election 2006 — Poll-by-poll results, Official Voting Results. Canada. Retrieved 2006-12-08. (Requires navigation to Prince George—Peace River)

- Elections Canada (2011). "Prince George—Peace River". Forty-First General Election 2011 — Poll-by-poll results, Official Voting Results. Canada. Retrieved 2011-11-11. (Requires navigation to Prince George—Peace River)

- "Emperor's Challenge". EmperorsChallenge.com. 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- Environmental Assessment Office (June 9, 2006). "Brule Mine Project Assessment Report" (PDF). British Columbia. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- "Fire forces 'hectic' evacuation in northern B.C.". CBC News. July 4, 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- "Grizfest". TumblerRidge.ca. 2007. Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- Gunton, Thomas (2003). "Megaprojects and Regional Development: Pathologies in Project Planning". Regional Studies: the Journal of the Regional Studies Association. Routledge. 37 (5): 505–519. doi:10.1080/0034340032000089068.

- Halseth, Greg; King, Nora; Ryser, Laura (January 2004). "Communication Tools and Resources in Rural Canada: A Report for Tumbler Ridge, British Columbia Initiative on the New Economy" (PDF). Canadian Rural Revitalization Foundation. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- Halseth, Greg; Sullivan, Lana (2002). "Building community in an instant town: A social geography of Mackenzie and Tumbler Ridge, British Columbia". University of Northern British Columbia Press. ISBN 1-896315-10-0.

- Halseth, Greg; Sullivan, Lana (2003–2004). "From Kitimat to Tumbler Ridge: A Crucial Lesson Not Learned in Resource-Town Planning". Western Geography. 13/14: 132–160..

- Helm, Charles (2000). "Beyond Rock and Coal: The History of the Tumbler Ridge Area". MCA Publishing..

- Helm, Charles (2001). "Tumbler Ridge: Enjoying its History, Trails and Wilderness". MCA Publishing. ISBN 0-9688558-0-6..

- McCrea, Richard; Lisa G. Buckley (2003). "Tumbler Ridge Dinosaur Excavation: Summer 2003". Living Landscapes. Royal British Columbia Museum. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

- "Province Approves Brule Mine Project" (PDF) (Press release). Ministry of Environment, British Columbia. July 6, 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- "More layoffs in northeast B.C.". CBC News. June 24, 1999. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- Peace Liard Employment Development Association (October 1985). "Peace Liard Economic Profile". Vol. 4.

- Police Services Division, Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General (ed.). Police and Crime: Summary Statistics: 1996–2005 (2006 ed.). British Columbia. ISSN 1198-9971. OCLC 34339976. Retrieved 2006-12-09.

- Reed Construction (2005). Municipal redbook: an authoritative reference guide to local government in British Columbia. Burnaby, BC. ISSN 0068-161X.

- School District 59 (Peace River South) (2005). "Board of School Trustees". SD59.bc.ca. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2006-12-09.

- Statistics Canada (July 25, 2006). "Community Highlights for Tumbler Ridge". 2001 Community Profiles. Canada. Retrieved 2006-12-09.

- Statistics Canada (September 12, 2007). "Community Highlights for Tumbler Ridge". 2006 Community Profiles. Canada. Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- Thompson, Berwick, Pratt & Partners, and subconsultants (March 25, 1978). "Conceptual Plan: Tumbler Ridge: Northeast Sector, B.C.: A Physical Plan/Social Plan/Financial Plan/Organizational Plan". Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, British Columbia.

- Tumbler Ridge (December 2004). "Business Information Package" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-05-17. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- Tumbler Ridge (2006). "Flying to Tumbler Ridge". TumblerRidge.ca. Archived from the original on 2006-06-21. Retrieved 2006-12-09.

- "Tumbler Ridge gets $6-million bail out". CBC News. October 27, 2000. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- "Tumbler Ridge looks ready for the builders". Alaska Highway News. 1981-12-30.

- Tumbler Ridge Museum Foundation (2008). "Tumbler Ridge Museum and Dinosaur Centre". TumblerRidgeMuseum.com. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

- Western Canadian Coal (October 2003). "Wolverine Coal Project: Revised Project Description" (PDF). Environmental Assessment Office. Retrieved 2006-12-09.

- Western Canadian Coal (2007). "Properties". WesternCoal.com. Retrieved 2008-01-20. (Requires navigation to Brazion Group and Wolverine Group categories.)

- Western Canadian Coal (2007). "Wolverine Group". WesternCoal.com. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

External links