Tubulin

| Tubulin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

kif1a head-microtubule complex structure in atp-form | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Tubulin | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00091 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0442 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR003008 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00201 | ||||||||

| SCOP | 1tub | ||||||||

| SUPERFAMILY | 1tub | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Tubulin in molecular biology can refer either to the tubulin protein superfamily of globular proteins, or one of the member proteins of that superfamily. α- and β-tubulins polymerize into microtubules, a major component of the eukaryotic cytoskeleton.[1] Microtubules function in many essential cellular processes, including mitosis. Tubulin-binding drugs kill cancerous cells by inhibiting microtubule dynamics, which are required for DNA segregation and therefore cell division.

In eukaryotes including humans there are 6 genes encoding tubulin (see below). Both α and β tubulins have a mass of around 50 kDa and are thus in a similar range compared to actin with ~42 kDa. In contrast, tubulin polymers (microtubules) tend to be much bigger than actin filaments due to their cylindrical nature.

Tubulin was long thought to be specific to eukaryotes. More recently, however, several prokaryotic proteins have been shown to be related to tubulin.[2][3][4][5]

Characterization

Tubulin is characterized by the evolutionarily conserved Tubulin/FtsZ family, GTPase protein domain.

This GTPase protein domain is found in all eukaryotic tubulin chains,[6] as well as the bacterial protein TubZ,[5] the archaeal protein CetZ,[7] and the FtsZ protein family widespread in Bacteria and Archaea.[2][8]

Function

Microtubules

α- and β-tubulin polymerize into dynamic microtubules. In eukaryotes, microtubules are one of the major components of the cytoskeleton, and function in many processes, including structural support, intracellular transport, and DNA segregation.

Microtubules are assembled from dimers of α- and β-tubulin. These subunits are slightly acidic with an isoelectric point between 5.2 and 5.8.[10] Each has a molecular weight of approximately 50,000 Daltons.[11]

To form microtubules, the dimers of α- and β-tubulin bind to GTP and assemble onto the (+) ends of microtubules while in the GTP-bound state.[12] The β-tubulin subunit is exposed on the plus end of the microtubule while the α-tubulin subunit is exposed on the minus end. After the dimer is incorporated into the microtubule, the molecule of GTP bound to the β-tubulin subunit eventually hydrolyzes into GDP through inter-dimer contacts along the microtubule protofilament.[13] Whether the β-tubulin member of the tubulin dimer is bound to GTP or GDP influences the stability of the dimer in the microtubule. Dimers bound to GTP tend to assemble into microtubules, while dimers bound to GDP tend to fall apart; thus, this GTP cycle is essential for the dynamic instability of the microtubule.

Bacterial microtubules

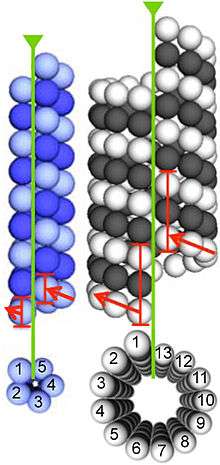

Homologs of α- and β-tubulin have been identified in the Prosthecobacter genus of bacteria.[3] They are designated BtubA and BtubB to identify them as bacterial tubulins. Both exhibit homology to both α- and β-tubulin.[14] While structurally highly similar to eukaryotic tubulins, they have several unique features, including chaperone-free folding and weak dimerization.[15] Electron cryomicroscopy showed that BtubA/B form microtubules in vivo, and that these microtubules comprise only five protofilaments, in contrast to eukaryotic microtubules, which usually contain 13.[16]

Prokaryotic division

FtsZ is found in nearly all Bacteria and Archaea, where it functions in cell division, localizing to a ring in the middle of the dividing cell and recruiting other components of the divisome, the group of proteins that together constrict the cell envelope to pinch off the cell, yielding two daughter cells. FtsZ can polymerize into tubes, sheets, and rings in vitro, and forms dynamic filaments in vivo.

TubZ functions in segregating low copy-number plasmids during bacterial cell division. The protein forms a structure unusual for a tubulin homolog; two helical filaments wrap around one another.[17] This may reflect an optimal structure for this role since the unrelated plasmid-partitioning protein ParM exhibits a similar structure.[18]

Cell shape

CetZ functions in cell shape changes in pleomorphic Haloarchaea. In Haloferax volcanii, CetZ forms dynamic cytoskeletal structures required for differentiation from a plate-shaped cell form into a rod-shaped form that exhibits swimming motility.[7]

Types

Eukaryotic

The tubulin superfamily contains six families of tubulins (alpha-, beta-, gamma-, delta-, epsilon and zeta-tubulins).[19]

α-Tubulin

Human α-tubulin subtypes include:

β-Tubulin

All drugs that are known to bind to human tubulin bind to β-tubulin.[20] These include paclitaxel, colchicine, and the vinca alkaloids, each of which have a distinct binding site on β-tubulin.[20]

Class III β-tubulin is a microtubule element expressed exclusively in neurons,[21] and is a popular identifier specific for neurons in nervous tissue. It binds colchicine much more slowly than other isotypes of β-tubulin.[22]

β1-tubulin, sometimes called class VI β-tubulin,[23] is the most divergent at the amino acid sequence level.[24] It is expressed exclusively in megakaryocytes and platelets in humans and appears to play an important role in the formation of platelets.[24]

Katanin is a protein complex that severs microtubules at β-tubulin subunits, and is necessary for rapid microtubule transport in neurons and in higher plants.[25]

Human β-tubulins subtypes include:

γ-Tubulin

γ-Tubulin, another member of the tubulin family, is important in the nucleation and polar orientation of microtubules. It is found primarily in centrosomes and spindle pole bodies, since these are the areas of most abundant microtubule nucleation. In these organelles, several γ-tubulin and other protein molecules are found in complexes known as γ-tubulin ring complexes (γ-TuRCs), which chemically mimic the (+) end of a microtubule and thus allow microtubules to bind. γ-tubulin also has been isolated as a dimer and as a part of a γ-tubulin small complex (γTuSC), intermediate in size between the dimer and the γTuRC. γ-tubulin is the best understood mechanism of microtubule nucleation, but certain studies have indicated that certain cells may be able to adapt to its absence, as indicated by mutation and RNAi studies that have inhibited its correct expression.

Human γ-tubulin subtypes include:

Members of the γ-tubulin ring complex:

δ and ε-Tubulin

Delta (δ) and epsilon (ε) tubulin have been found to localize at centrioles and may play a role in forming the mitotic spindle during mitosis, though neither is as well-studied as the α- and β- forms.

Human δ- and ε-tubulin subtypes include:

ζ-Tubulin

Zeta-tubulin is present only in kinetoplastid protozoa.[19]

Prokaryotic

BtubA/B

BtubA/B are found in some bacterial species in the Verrucomicrobial genus Prosthecobacter.[3] Their evolutionary relationship to eukaryotic tubulins is unclear, although they may have descended from a eukaryotic lineage by lateral gene transfer.[15][26]

FtsZ

Nearly all bacterial and archaeal cells use FtsZ to divide.[27] It was the first prokaryotic cytoskeletal protein identified.

TubZ

TubZ was identified in Bacillus thuringiensis as essential for plasmid maintenance.[5]

CetZ

CetZ is found in the euryarchaeal clades of Methanomicrobia and Halobacteria, where it functions in cell shape differentiation.[7]

Pharmacology

Tubulins are targets for anticancer drugs like Taxol, Tesetaxel and the "Vinca alkaloid" drugs such as vinblastine and vincristine. The anti-gout agent colchicine binds to tubulin and inhibits microtubule formation, arresting neutrophil motility and decreasing inflammation. The anti-fungal drug Griseofulvin targets microtubule formation and has applications in cancer treatment.

Post-translational modifications

When incorporated into microtubules, tubulin accumulates a number of post-translational modifications, many of which are unique to these proteins. These modifications include detyrosination, acetylation, polyglutamylation, polyglycylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation, and palmitoylation. Tubulin is also prone to oxidative modification and aggregation during, for example, acute cellular injury.[28]

Nowadays there are many scientific investigations of the acetylation done in some microtubules, specially the one one by α-tubulin N-acetyltransferase (ATAT1) which is being demonstrated to play an important role in many biological and molecular functions and, therefore, it is also associated with many human diseases, specially neurological diseases.

See also

References

- ↑ Gunning PW, Ghoshdastider U, Whitaker S, Popp D, Robinson RC (June 2015). "The evolution of compositionally and functionally distinct actin filaments". Journal of Cell Science. 128 (11): 2009–19. doi:10.1242/jcs.165563. PMID 25788699.

- 1 2 Nogales E, Downing KH, Amos LA, Löwe J (June 1998). "Tubulin and FtsZ form a distinct family of GTPases". Nature Structural Biology. 5 (6): 451–8. doi:10.1038/nsb0698-451. PMID 9628483.

- 1 2 3 Jenkins C, Samudrala R, Anderson I, Hedlund BP, Petroni G, Michailova N, Pinel N, Overbeek R, Rosati G, Staley JT (December 2002). "Genes for the cytoskeletal protein tubulin in the bacterial genus Prosthecobacter". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (26): 17049–54. doi:10.1073/pnas.012516899. PMC 139267

. PMID 12486237.

. PMID 12486237. - ↑ Yutin N, Koonin EV (March 2012). "Archaeal origin of tubulin". Biology Direct. 7: 10. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-7-10. PMC 3349469

. PMID 22458654.

. PMID 22458654. - 1 2 3 Larsen RA, Cusumano C, Fujioka A, Lim-Fong G, Patterson P, Pogliano J (June 2007). "Treadmilling of a prokaryotic tubulin-like protein, TubZ, required for plasmid stability in Bacillus thuringiensis". Genes & Development. 21 (11): 1340–52. doi:10.1101/gad.1546107. PMC 1877747

. PMID 17510284.

. PMID 17510284. - ↑ Nogales E, Wolf SG, Downing KH (January 1998). "Structure of the alpha beta tubulin dimer by electron crystallography". Nature. 391 (6663): 199–203. Bibcode:1998Natur.391..199N. doi:10.1038/34465. PMID 9428769.

- 1 2 3 Duggin IG, Aylett CH, Walsh JC, Michie KA, Wang Q, Turnbull L, Dawson EM, Harry EJ, Whitchurch CB, Amos LA, Löwe J (March 2015). "CetZ tubulin-like proteins control archaeal cell shape". Nature. 519 (7543): 362–5. doi:10.1038/nature13983. PMC 4369195

. PMID 25533961.

. PMID 25533961. - ↑ Löwe J, Amos LA (January 1998). "Crystal structure of the bacterial cell-division protein FtsZ". Nature. 391 (6663): 203–6. Bibcode:1998Natur.391..203L. doi:10.1038/34472. PMID 9428770.

- ↑ Pilhofer M, Ladinsky MS, McDowall AW, Petroni G, Jensen GJ (December 2011). "Microtubules in bacteria: Ancient tubulins build a five-protofilament homolog of the eukaryotic cytoskeleton". PLoS Biology. 9 (12): e1001213. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001213. PMC 3232192

. PMID 22162949.

. PMID 22162949. - ↑ Williams RC, Shah C, Sackett D (November 1999). "Separation of tubulin isoforms by isoelectric focusing in immobilized pH gradient gels". Analytical Biochemistry. 275 (2): 265–7. doi:10.1006/abio.1999.4326. PMID 10552916.

- ↑ "tubulin in Protein sequences". EMBL-EBI.

- ↑ Heald R, Nogales E (January 2002). "Microtubule dynamics". Journal of Cell Science. 115 (Pt 1): 3–4. PMID 11801717.

- ↑ Howard J, Hyman AA (April 2003). "Dynamics and mechanics of the microtubule plus end". Nature. 422 (6933): 753–8. Bibcode:2003Natur.422..753H. doi:10.1038/nature01600. PMID 12700769.

- ↑ Martin-Galiano AJ, Oliva MA, Sanz L, Bhattacharyya A, Serna M, Yebenes H, Valpuesta JM, Andreu JM (June 2011). "Bacterial tubulin distinct loop sequences and primitive assembly properties support its origin from a eukaryotic tubulin ancestor". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 286 (22): 19789–803. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.230094. PMC 3103357

. PMID 21467045.

. PMID 21467045. - 1 2 Schlieper D, Oliva MA, Andreu JM, Löwe J (June 2005). "Structure of bacterial tubulin BtubA/B: evidence for horizontal gene transfer". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (26): 9170–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0502859102. PMC 1166614

. PMID 15967998.

. PMID 15967998. - ↑ Pilhofer M, Ladinsky MS, McDowall AW, Petroni G, Jensen GJ (December 2011). "Microtubules in bacteria: Ancient tubulins build a five-protofilament homolog of the eukaryotic cytoskeleton". PLoS Biology. 9 (12): e1001213. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001213. PMC 3232192

. PMID 22162949.

. PMID 22162949. - ↑ Aylett CH, Wang Q, Michie KA, Amos LA, Löwe J (November 2010). "Filament structure of bacterial tubulin homologue TubZ". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (46): 19766–71. doi:10.1073/pnas.1010176107. PMC 2993389

. PMID 20974911.

. PMID 20974911. - ↑ Bharat TA, Murshudov GN, Sachse C, Löwe J (July 2015). "Structures of actin-like ParM filaments show architecture of plasmid-segregating spindles". Nature. 523 (7558): 106–10. doi:10.1038/nature14356. PMC 4493928

. PMID 25915019.

. PMID 25915019. - 1 2 NCBI CCD cd2186

- 1 2 Zhou J, Giannakakou P (January 2005). "Targeting microtubules for cancer chemotherapy". Current Medicinal Chemistry. Anti-Cancer Agents. 5 (1): 65–71. doi:10.2174/1568011053352569. PMID 15720262.

- ↑ Karki R, Mariani M, Andreoli M, He S, Scambia G, Shahabi S, Ferlini C (April 2013). "βIII-Tubulin: biomarker of taxane resistance or drug target?". Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 17 (4): 461–72. doi:10.1517/14728222.2013.766170. PMID 23379899.

- ↑ Ludueña RF (May 1993). "Are tubulin isotypes functionally significant". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4 (5): 445–57. doi:10.1091/mbc.4.5.445. PMC 300949

. PMID 8334301.

. PMID 8334301. - ↑ "TUBB1 tubulin, beta 1 class VI [Homo sapiens (human)]". Gene - NCBI.

- 1 2 Lecine P, et al. (August 2000). "Hematopoietic-specific beta 1 tubulin participates in a pathway of platelet biogenesis dependent on the transcription factor NF-E2". Blood. 96 (4): 1366–73. PMID 10942379.

- ↑ McNally FJ, Vale RD (November 1993). "Identification of katanin, an ATPase that severs and disassembles stable microtubules". Cell. 75 (3): 419–29. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90377-3. PMID 8221885.

- ↑ Martin-Galiano AJ, Oliva MA, Sanz L, Bhattacharyya A, Serna M, Yebenes H, Valpuesta JM, Andreu JM (June 2011). "Bacterial tubulin distinct loop sequences and primitive assembly properties support its origin from a eukaryotic tubulin ancestor". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 286 (22): 19789–803. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.230094. PMC 3103357

. PMID 21467045.

. PMID 21467045. - ↑ Margolin, William (2005-11-01). "FtsZ and the division of prokaryotic cells and organelles". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 6 (11): 862–871. doi:10.1038/nrm1745. ISSN 1471-0072.

- ↑ Samson AL, Knaupp AS, Sashindranath M, Borg RJ, Au AE, Cops EJ, Saunders HM, Cody SH, McLean CA, Nowell CJ, Hughes VA, Bottomley SP, Medcalf RL (October 2012). "Nucleocytoplasmic coagulation: an injury-induced aggregation event that disulfide crosslinks proteins and facilitates their removal by plasmin". Cell Reports. 2 (4): 889–901. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2012.08.026. PMID 23041318.

External links

- Tubulin at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- EC 3.6.5.6

- protocol for purification of tubulin from bovine brain