Treaty of London (1839)

The Treaty of London of 1839, also called the First Treaty of London, the Convention of 1839, the Treaty of Separation, the Quintuple Treaty of 1839, or the Treaty of the XXIV articles, was a treaty signed on 19 April 1839 between the Concert of Europe, the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Kingdom of Belgium. It was a direct follow-up to the 1831 Treaty of the XVIII Articles which the Netherlands had refused to sign, and the result of negotiations at the London Conference of 1838–1839.[1]

Under the treaty, the European powers recognized and guaranteed the independence and neutrality of Belgium and established the full independence of the German-speaking part of Luxembourg. Article VII required Belgium to remain perpetually neutral, and by implication committed the signatory powers to guard that neutrality in the event of invasion.[2]

Background

Since 1815, Belgium had been a part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. In 1830 Catholic Belgians broke away and established an independent Kingdom of Belgium. They could not accept the Dutch king's favouritism toward Protestantism and his disdain for the French language. Outspoken liberals regarded King William I's rule as despotic. There were high levels of unemployment and industrial unrest among the working classes. There was small-scale fighting but it took years before the Netherlands finally recognized defeat. In 1839 the Dutch accepted Belgian independence by signing the Treaty of London. The major powers guaranteed Belgian independence.[3][4]

Territorial consequences

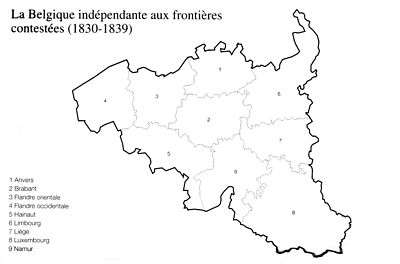

With the treaty, the southern provinces of the Netherlands became internationally recognized as the Kingdom of Belgium (which it was de facto since 1830), while the province of Limburg was split into Belgian and Dutch parts.

The same happened to the Grand Duchy of Luxemburg which lost two-thirds of its territory to the new Province of Luxembourg in what is termed the 'Third Partition of Luxembourg'. This left a rump Grand Duchy, covering one-third of the original territory and inhabited by one-half of the original population,[5] in personal union with the Netherlands, under King-Grand Duke William I (and subsequently William II and William III). This arrangement was confirmed by the 1867 Treaty of London,[6] known as the 'Second Treaty of London' in reference to the 1839 treaty, and lasted until the death of King-Grand Duke William III 23 November 1890.[7]

"Scrap of paper"

Belgium's de facto independence had been established through nine years of intermittent fighting. The co-signatories of the Treaty of London—Great Britain, Austria, France, the German Confederation (led by Prussia), Russia, and the Netherlands—now officially recognised the independent Kingdom of Belgium, and at Britain's insistence agreed to its neutrality.

The treaty was a fundamental "lawmaking" treaty that became a cornerstone of European international law; it was especially important in the events leading up to World War I.[9] When the German Empire invaded Belgium in August 1914 in violation of the treaty, the British declared war on 4 August.[10][11] Informed by the British ambassador that Britain would go to war with Germany over the latter's violation of Belgian neutrality, German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg exclaimed that he could not believe that Britain and Germany would be going to war over a mere "scrap of paper."[12]

Iron Rhine

The Treaty of London also guaranteed Belgium the right of transit by rail or canal over Dutch territory as an outway to the German Ruhr. This right was reaffirmed in a 24 May 2005 ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in a dispute between Belgium and the Netherlands on the railway track.[13]

In 2004 Belgium requested a reopening of the Iron Rhine. This was the result of the increasing transport of goods between the port of Antwerp and the German Ruhr Area. As part of the European policy of modal shift on the increasing traffic of goods, transport over railway lines and waterways is preferred over road transport. The Belgian request was based on the treaty of 1839, and the Iron Rhine Treaty of 1873.[14] After a series of failed negotiations, the Belgian and Dutch governments agreed to take the issue to the Permanent Court of Arbitration and respect its ruling in the case.

In its ruling of 24 May 2005, the court acknowledged both the Belgian rights under the cessation treaty of 1839 and the Dutch concerns for part of the Meinweg National Park nature reserve. The 1839 treaty still applies, the court found, giving Belgium the right to use and modernise the Iron Rhine. However, it has to finance the modernisation of the line, while the Netherlands have to fund the repairs and maintenance of the route. Both countries will split the costs of the construction of a tunnel beneath the nature reserve.[15]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Eric Van Hooydonk (2006). "Chapter 15". In Aldo E. Chircop, O. Lindén. Places of Refuge: The Belgian Experience. Places of Refuge for Ships: Emerging Environmental Concerns of a Maritime Custom. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff. p. 417. ISBN 9789004149526. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- ↑ Eric Van Hooydonk (2006). "Chapter 15". In Aldo E. Chircop, O. Lindén. Places of Refuge: The Belgian Experience. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff. p. 417. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- ↑ E.H. Kossmann, The Low Countries 1780–1940 (1978) pp 151–54

- ↑ Paul W. Schroeder, The Transformation of European Politics 1763–1848 (1994) pp 671–91

- ↑ Calmes (1989), p. 316

- ↑ Kreins (2003), pp. 80–1

- ↑ Kriens (2003), p. 83

- ↑ Te Papa (the Museum of New Zealand)'s description of the poster.

- ↑ Hull, Isabel V. (2014). A Scrap of Paper: Breaking and Making International Law during the Great War. Cornell University Press. p. 17. ISBN 9780801470646. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- ↑ Cook, Chris; Stevenson, John (2005). The Routledge companion to European history since 1763. Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 9780415345835.

- ↑ Why did Britain go to War?, The National Archives, retrieved 30 April 2016

- ↑ Larry Zuckerman (2004). The Rape of Belgium: The Untold Story of World War I. New York University Press. p. 43. ISBN 9780814797044.

- ↑ "Iron Rhine Arbitration (Belgium/Netherlands)". The Hague Justice Portal. 24 May 2005. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ "Iron Rhine Arbitration, Belgium v Netherlands, Award, ICGJ 373 (PCA 2005), 24th May 2005, Permanent Court of Arbitration [PCA]". Oxford Public Law International. 24 May 2005. doi:10.1093/law:icgj/373pca05.case.1/law-icgj-373pca05 (inactive 2016-08-24). Retrieved 30 April 2016.

Letter of the Belgian Minister of Transport to the Dutch Minister of Transport and Waterstaat, dated 23 February 1987 ... In my view, such a limitation would go against the rights accorded to Belgium by Article 12 of the Treaty of London of 19 April 1839 between Belgium and the Netherlands, which was executed through the Treaty of 13 January 1873 regulating the passage of the railway Antwerp-Gladbach through the territory of Limburg. In the above context, it is beyond doubt that Belgium will hold firm to its right of free transport through the Iron Rhine.

- ↑ "Iron rhine Arbitral Tribunal Renders Awards" (PDF) (Press release). Permanent Court of Arbitration. 24 May 2005. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

Further reading

- Calmes, Christian (1989). The Making of a Nation From 1815 to the Present Day. Luxembourg City: Saint-Paul.

- Omond. G. W. T. "The Question of the Netherlands in 1829–1830," Transactions of the Royal Historical Society (1919) pp. 150–171 in JSTOR

- Schroeder, Paul W. The Transformation of European Politics, 1763–1848 (1994) pp 716–18

- Kreins, Jean-Marie (2003). Histoire du Luxembourg (in French) (3rd ed.). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 978-2-13-053852-3.

Primary sources

- Sanger, Charles Percy, and Henry Tertius James Norton. England's guarantee to Belgium and Luxemburg: with the full text of the treaties (1915). online

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Treaty of London (1839). |