Traveller (horse)

Traveller and Robert E. Lee | |

| Other name(s) | Greenbrier |

|---|---|

| Species | Equus ferus caballus |

| Breed | American Saddlebred |

| Sex | Male |

| Born |

1857 Near Blue Sulphur Springs, Greenbrier County, Virginia |

| Died | 1871 |

| Resting place | Washington and Lee University |

| Owner | General Robert E. Lee |

| Weight | 1,100 pounds (500 kg) |

| Height | 16 hands (64 inches, 163 cm) |

| Appearance | Gray in color with black points |

Traveller (1857–1871) was Confederate General Robert E. Lee's most famous horse during the American Civil War. He was a grey American Saddlebred of 16 hands, notable for speed, strength and courage in combat. Lee acquired him in February 1862, and rode him in many battles. Traveller outlived Lee by only a few months, and had to be shot when he contracted untreatable tetanus. His name is often misspelled with a single ‘L’ in the American style, though Lee actually used the British-style double ‘L’.

Birth and war service

Traveller, originally named Greenbrier, was born near the Blue Sulphur Springs, in Greenbrier County, Virginia (now West Virginia) and raised by Andrew Johnston. An American Saddlebred, he was of Grey Eagle stock;[1] as a colt, he took the first prize at the Lewisburg, Virginia fairs in 1859 and 1860. As an adult he was a sturdy horse, 16 hands (64 inches, 163 cm) high and 1,100 pounds (500 kg), iron gray in color with black points, a long mane and a flowing tail.

In the spring of 1861, a year before achieving fame as a Confederate general, Robert E. Lee was commanding a small force in western Virginia. The quartermaster of the 3rd Regiment, Wise Legion,[2][3] Captain Joseph M. Broun, was directed to "purchase a good serviceable horse of the best Greenbrier stock for our use during the war." Broun purchased the horse for $175 (approximately $4,545 in 2008)[4] from Andrew Johnston's son, Captain James W. Johnston, and named him Greenbrier. Major Thomas L. Broun, Joseph's brother recalled that Greenbrier:

... was greatly admired in camp for his rapid, springy walk, his high spirit, bold carriage, and muscular strength. He needed neither whip nor spur, and would walk his five or six miles an hour over the rough mountain roads of Western Virginia with his rider sitting firmly in the saddle and holding him in check by a tight rein, such vim and eagerness did he manifest to go right ahead so soon as he was mounted.— Major Thomas L. Broun

General Lee took a great fancy to the horse. He called him his "colt", and predicted to Broun that he would use it before the war was over. After Lee was transferred to South Carolina, Joseph Broun sold the horse to him for $200 in February 1862. Lee named the horse "Traveller" (spelling the word with a double "L" in the British style).

Lee described his horse in a letter in response to his wife's cousin, Markie Williams, who wished to paint a portrait of Traveller:

If I was an artist like you, I would draw a true picture of Traveller; representing his fine proportions, muscular figure, deep chest, short back, strong haunches, flat legs, small head, broad forehead, delicate ears, quick eye, small feet, and black mane and tail. Such a picture would inspire a poet, whose genius could then depict his worth, and describe his endurance of toil, hunger, thirst, heat and cold; and the dangers and suffering through which he has passed. He could dilate upon his sagacity and affection, and his invariable response to every wish of his rider. He might even imagine his thoughts through the long night-marches and days of the battle through which he has passed. But I am no artist Markie, and can therefore only say he is a Confederate gray.— Robert E. Lee, letter to Markie Williams

Traveller was a horse of great stamina and was usually a good horse for an officer in battle because he was difficult to frighten. He could sometimes become nervous and spirited, however. At the Second Battle of Bull Run, while General Lee was at the front reconnoitering, dismounted and holding Traveller by the bridle, the horse became frightened at some movement of the enemy and, plunging, pulled Lee down on a stump, breaking both of his hands. Lee went through the remainder of that campaign chiefly in an ambulance. When he rode on horseback, a courier rode in front leading his horse.

After the war, Traveller accompanied Lee to Washington College in Lexington, Virginia. He lost many hairs from his tail to admirers (veterans and college students) who wanted a souvenir of the famous horse and his general. Lee wrote to his daughter Mildred that "the boys are plucking out his tail, and he is presenting the appearance of a plucked chicken."[5]

Death and burials

In 1870, during Lee's funeral procession, Traveller was led behind the caisson bearing the General's casket, his saddle and bridle draped with black crepe. Not long after Lee's death, in 1871, Traveller stepped on a nail and developed tetanus. There was no cure, and he was shot to relieve his suffering.

Traveller was initially buried behind the main buildings of the college, but was unearthed by persons unknown and his bones were bleached for exhibition in Rochester, New York, in 1875/1876. In 1907, Richmond journalist Joseph Bryan paid to have the bones mounted and returned to the college, named Washington and Lee University since Lee's death, and they were displayed in the Brooks Museum, in what is now Robinson Hall. The skeleton was periodically vandalized there by students who carved their initials in it for good luck. In 1929, the bones were moved to the museum in the basement of the Lee Chapel, where they stood for 30 years, deteriorating with exposure.

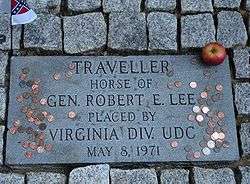

Finally in 1971, Traveller's remains were buried in a wooden box encased in concrete next to the Lee Chapel on the Washington & Lee campus, a few feet away from the Lee family crypt inside, where his master's body rests. The stable where he lived his last days, directly connected to the Lee House on campus, traditionally stands with its doors left open; this is said to allow his spirit to wander freely. The 24th President of Washington & Lee (and thus a recent resident of Lee House), Thomas Burish, caught strong criticism from many members of the Washington & Lee community for closing the stable gates in violation of this tradition. Burish later had the doors to the gates repainted in a dark green color, which he referred to in campus newspapers as "Traveller Green".

The base newspaper of the United States Army's Fort Lee, located in Petersburg, Virginia, is named Traveller.

Traveller remains known to Washington and Lee students, and is the namesake of the University's Safe Ride Program. Students are known to say, "Call Traveller and you will get home safely."

Traveller in verse

- And now at last,

- Comes Traveller and his master. Look at them well.

- The horse is an iron-grey, sixteen hands high,

- Short back, deep chest, strong haunch, flat legs, small head,

- Delicate ear, quick eye, black mane and tail,

- Wise brain, obedient mouth.

- Such horses are

- The jewels of the horseman's hands and thighs,

- They go by the word and hardly need the rein.

- They bred such horses in Virginia then,

- Horses that were remembered after death

- And buried not so far from Christian ground

- That if their sleeping riders should arise

- They could not witch them from the earth again

- And ride a printless course along the grass

- With the old manage and light ease of hand.

- — Passage from "Army of Northern Virginia", a poem by Stephen Vincent Benet[6]

- Their sleepless, bloodshot eyes were turned to me.

- Their flags hung black against the pelting sky.

- Their jests and curses echoed whisperingly,

- As though from long-lost years of sorrow - Why,

- You're weeping! What, then? What more did you see?

- A gray man on a gray horse rode by.

- — Passage from Traveller, a novel by Richard Adams

Lee's other horses

Although the most famous, Traveller was not Lee's only horse during the war:

- Lucy Long, a mare, was the primary backup horse to Traveller. She remained with the Lee family after the war, dying considerably after Lee, when she was thirty-four years old. She was a gift from J.E.B. Stuart who purchased her from Adam Stephen Dandridge of The Bower. Notably, she was ridden by Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville.

- Richmond, a bay colored stallion, was acquired by General Lee in early 1861. He died in 1862 after the Battle of Malvern Hill.

- Brown-Roan, or The Roan, was purchased by Lee in West Virginia around the time of Traveller's purchase. He went blind in 1862 and had to be retired.

- Ajax, a sorrel horse, was too large for Lee to ride comfortably and was thus used infrequently.

James Longstreet, one of Lee's most trusted generals, was referred to by Lee as his Old War Horse because of his reliability. After the Civil War, many Southerners were angered by Longstreet's defection to the Republican Party and blamed him for their defeat in the Civil War. However, Lee supported reconciliation and was pleased with how Longstreet had fought in the War. This nickname was Lee's symbol of trust.

In popular media

- Moonrunners (a 1975 movie that spawned the TV series The Dukes of Hazzard) featured a dirt-track racing car, a 1955 Chevrolet, with a Confederate flag on the roof, named "Traveller". (Traveller was later transformed into the painted up street car, a 1969 Dodge Charger, known as the "General Lee" in the TV series.)

- Adams, Richard. Traveller New York: Knopf, 1988. ISBN 0-440-20493-3. A fictional first-person narrative, in dialect, by Traveller. His equine memoirs are told to a cat in the stable of the retired general. New York Times book review.

- In Bronco Benny, from the Belgian comic Les Tuniques Bleues, Traveller has a major role. Only Bronco Benny, best horse tamer of the Union, is able to break in the proud horse. His capture cause war with Natives Americans who see Traveller as a divinity. In the end, when the heroes fake death, Lee doesn't notice them but Traveller does and displays a little affection for them.

See also

Notes

- ↑ American Saddlebred magazine, November/December 1998.

- ↑ Dickinson, Jack L. Tattered Uniforms and Bright Bayonets: West Virginia's Confederate Soldiers. Huntington: Marshall University Library Associates, 1995

- ↑ Broun, Thomas L. Letter to Annie Broun. 16 Sept. 1861. Southern Historical Collection. Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC.

- ↑ Inflation counter

- ↑ "Robert Lee letter to Mildred Lee, 29 October 1865". Family Tales. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ↑ http://oldpoetry.com/poetry/38925

References

- Southern Historical Society Papers, Richmond, Va., January–December, 1890.

- Lee's Horses at Stratford Hall website

- General Lee's Traveller, On the Campus of Washington and Lee, brochure published by the Lee Chapel Museum, 2005.

- Magner, Blake A. Traveller & Company, The Horses of Gettysburg. Gettysburg, PA: Farnsworth House Military Impressions, 1995. ISBN 0-9643632-2-4.

- From War Horse To Saddle Horse, American Saddlebred, November/December 1998.

External links

- General Lee and Traveller, a poem by Rev. Robert Tuttle

- Traveller at Find a Grave