Torcello

|

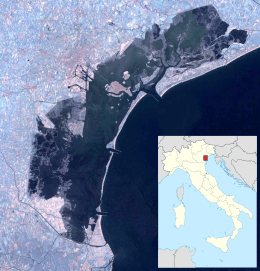

View of Torcello | |

Torcello | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 45°29′52″N 12°25′07″E / 45.497902°N 12.418583°ECoordinates: 45°29′52″N 12°25′07″E / 45.497902°N 12.418583°E |

| Adjacent bodies of water | Venetian Lagoon |

| Administration | |

| Region | Veneto |

| Province | Province of Venice |

Torcello is a sparsely populated[1] island at the northern end of the Venetian Lagoon, in north-eastern Italy. It is the oldest continuously populated region of Venice, and once held the largest population of the Republic of Venice.

History

After the downfall of the Western Roman Empire, Torcello was one of the first lagoon islands to be successively populated by those Veneti who fled the terra ferma (mainland) to take shelter from the recurring barbarian invasions, especially after Attila the Hun had destroyed the city of Altinum and all of the surrounding settlements in 452.[2] Although the hard-fought Veneto region formally belonged to the Byzantine Exarchate of Ravenna since the end of the Gothic War, it remained unsafe on account of frequent Germanic invasions and wars: during the following 200 years the Lombards and the Franks fuelled a permanent influx of sophisticated urban refugees to the island’s relative safety, including the Bishop of Altino himself. In 638, Torcello became the bishop’s official see for more than a thousand years and the people of Altinum brought with them the relics of Saint Heliodorus, now the patron saint of the island.

Torcello benefited from and maintained close cultural and trading ties with Constantinople: however, being a rather distant outpost of the Eastern Roman Empire, it could establish de facto autonomy from the eastern capital.

Torcello rapidly grew in importance as a political and trading centre: in the 10th century it had a population often estimated at 10,000-30,000 people although more recent estimates by archeologists place it at closer to a maximum of 3,000.[3] In pre-Medieval times, Torcello was much a more powerful trading center than Venice.[4] Thanks to the lagoon’s salt marshes, the salines became Torcello’s economic backbone and its harbour developed quickly into an important re-export market in the profitable east-west-trade, which was largely controlled by Byzantium during that period.[2] The lagoon around the island of Torcello gradually became a swamp from the 12th century onwards bringing malaria-carrying mosquitos, and Torcello’s heyday came to an end: navigation in the laguna morta (dead lagoon) was impossible before long and the growing swamps seriously aggravated the malaria situation, so that the population eventually abandoned the island and left for Murano, Burano or Venice.[2] It now has a full-time population of 10 people, including the parish priest.[1]

Sights

Torcello's numerous palazzi, its twelve parishes and its sixteen cloisters have almost disappeared since the Venetians recycled the useful building material. The only remaining medieval buildings form an ensemble of four edifices.

Today's main attraction is the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta, founded in 639. It is of basilica-form with side aisles but no crossing, and has much 11th and 12th century Byzantine work, including mosaics (e.g. a vivid version of the Last Judgement). Other attractions include the 11th and 12th century Church of Santa Fosca, in the form of a Greek cross, which is surrounded by a semi-octagonal porticus, and the Museo Provinciale di Torcello housed in two fourteenth century palaces, the Palazzo dell'Archivio and the Palazzo del Consiglio, which was once the seat of the communal government. Another noteworthy sight for tourists is an ancient stone chair, known as Attila’s Throne. It has, however, nothing to do with the king of the Huns, but it was most likely the podestà’s or the bishop’s chair. Torcello is also home to a Devil's Bridge, known as the Ponte del Diavolo or alternatively the Ponticello del Diavolo (devil's little bridge).

Famous residents

Ernest Hemingway spent some time there in 1948, writing parts of Across the River and Into the Trees. The novel contains representations of Torcello and its environs.[5]In addition, numerous famous artists, musicians, and movie stars have spent time on the island, a quiet refuge.[6]

Gallery

Central Torcello, with the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta and the Church of Santa Fosca

Central Torcello, with the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta and the Church of Santa Fosca Last Judgement. 12th-century Byzantine mosaic from Torcello Cathedral

Last Judgement. 12th-century Byzantine mosaic from Torcello Cathedral

Notes and references

- 1 2 "Torcello, l'isola che sta sparendo Restano dieci abitanti. E un prete". Corriere del Veneto. 28 June 2014. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 Frederic Chapin Lane (1973), Venice, a maritime republic, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0801814456

- ↑ Calaon, Diego (2013). Quando Torcello era abitata. Regione del Veneto. p. 73. OCLC 883623826.

- ↑ Norwich, John Julius (1982). A History of Venice. New York: Vintage Books. p. 672. ISBN 0679721975.

- ↑ Crevar, Alex (19 February 2006). "Torcello Offers a Refuge From the Tourist Crush". New York Times. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ↑ "Hotel Cipriani: Our Memories". Locanda Cipriani. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Torcello. |