Tommy Flowers

| Thomas Harold Flowers MBE | |

|---|---|

Tommy Flowers - possibly taken around the time he was at Bletchley Park | |

| Born |

22 December 1905 Poplar, London, England |

| Died |

28 October 1998 (aged 92) Mill Hill, London, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Title | Mr |

| Spouse(s) | Eileen Margaret Green |

| Children | 2 |

Thomas "Tommy" Harold Flowers, MBE (22 December 1905 – 28 October 1998) was an English engineer. During World War II, Flowers designed Colossus, the world's first programmable electronic computer, to help solve encrypted German messages.

Early life

Flowers was born at 160 Abbott Road, Poplar in London's East End on 22 December 1905, the son of a bricklayer.[1] Whilst undertaking an apprenticeship in mechanical engineering at the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, he took evening classes at the University of London to earn a degree in electrical engineering.[1] In 1926, he joined the telecommunications branch of the General Post Office (GPO), moving to work at the research station at Dollis Hill in north-west London in 1930. In 1935, he married Eileen Margaret Green and the couple later had two children, John and Kenneth.[1]

From 1935 onward, he explored the use of electronics for telephone exchanges. By 1939, he was convinced that an all-electronic system was possible. This background in switching electronics would prove crucial for his computer design in World War II.

World War II

Flowers's first contact with the wartime codebreaking effort came in February 1941[2] when his director, W. Gordon Radley was asked for help by Alan Turing, who was then working at the government's Bletchley Park codebreaking establishment 50 miles north west of London in Buckinghamshire. Turing wanted Flowers to build a decoder for the relay-based Bombe machine, which Turing had developed to help decrypt the Germans' Enigma codes. Although the decoder project was abandoned, Turing was impressed with Flowers's work, and in February 1943 introduced him to Max Newman who was leading the effort to automate part of the cryptanalysis of the Lorenz cipher. This was a high-level German cipher generated by a teletypewriter in-line cipher machine, the SZ40/42, one of their "Geheimschreiber" (secret writer) systems, that was called "Tunny" by the British. It was a much more complex system than Enigma; the decoding procedure involved trying so many possibilities that it was impractical to do by hand. Flowers and Frank Morrell (also at Dollis Hill) designed the Heath Robinson, the first machine designed to decrypt the Lorenz or “Fish” machine cyphers.

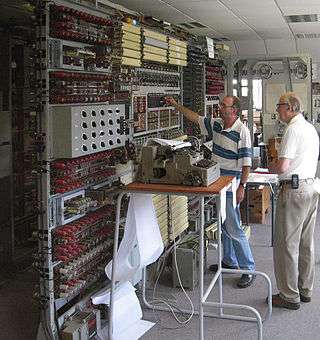

Flowers proposed an electronic system, which his staff called Colossus, using perhaps 1,800 thermionic valves (vacuum tubes), and having only one paper tape instead of two (which required synchronisation) by generating the wheel patterns electronically. Because the most complicated previous electronic device had used about 150 valves, some were sceptical that the system would be reliable. Flowers countered that the British telephone system used thousands of valves and was reliable because the electronics were operated in a stable environment with the circuitry on all the time. The Bletchley Park management were not convinced, however,[3] and merely encouraged Flowers to proceed on his own. He did so, providing much of the funds for the project himself. Flowers had first met (and got on with) Turing in 1939, but was treated with disdain by Gordon Welchman, because of his advocacy of valves rather than relays. Welchman preferred the views of Wynn-Williams and Keene of BTM (who had designed and constructed the Bombe), and wanted Radley and “Mr Flowers of Dollis Hill” removed from work on Colossus for “squandering good valves”.[4]

On 2 June 1943, Flowers was made a Member of the Order of the British Empire.[5][6]

Flowers gained full backing for his project from the director of Dollis Hill, W. G. Radley. With the highest priority for acquisition of parts, Flowers's extremely dedicated team at Dollis Hill built the first machine in 11 months. It was immediately dubbed 'Colossus' by the Bletchley Park staff for its immense proportions. The Mark 1 Colossus operated five times faster and was more flexible than the previous system, named Heath Robinson, which used electro-mechanical switches. The first Mark 1, with 1500 valves, ran at Dollis Hill in November 1943, and then at Bletchley Park in January 1944.

A Mark 2 redesign utilising 2,400 valves had begun before the first computer was finished, in anticipation of a need for additional computers. The first Mark 2 Colossus went into service at Bletchley Park on 1 June 1944, and immediately produced vital information for the imminent D-Day landings planned for Monday 5 June (postponed 24 hours by bad weather). Flowers later described a crucial meeting between Dwight D. Eisenhower and his staff on 5 June, during which a courier entered and handed Eisenhower a note summarising a Colossus decrypt. This confirmed that Hitler wanted no additional troops moved to Normandy, as he was still convinced that the preparations for the Normandy Landings were a diversionary feint. Handing back the decrypt, Eisenhower announced to his staff, "We go tomorrow."[7] Earlier, a report from Field Marshal Rommel on the western defences was decoded by Colossus and revealed that one of the sites chosen as the drop site for an US parachute division was the base for a German tank division. The site was changed.[8]

Years later, Flowers described the design and construction of these computers.[9] Ten Colossi were completed and used during World War II in British decoding efforts, and an eleventh was ready for commissioning at the end of the war. All but two were dismantled at the end of the war. "The remaining two were moved to a British Intelligence department, GCHQ in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, where they may have played a significant part in the codebreaking operations of the Cold War".[10] They were finally decommissioned in 1959 and 1960.

Post-war work and retirement

After the war, Flowers was granted £1,000 by the government, payment which did not cover Flowers' personal investment in the equipment and most of which he shared amongst the staff who helped him build and test Colossus. Ironically, Flowers applied for a loan from the Bank of England to build another machine like Colossus but was denied the loan because the bank did not believe that such a machine could work. He could not argue that he had already designed and built many of these machines because his work on Colossus was covered by the Official Secrets Act. His work in computing was not fully acknowledged until the 1970s. His family had known only that he had done some 'secret and important' work.[11] He remained at the Post Office Research Station where he was Head of the Switching Division. He and his group pioneered work on all-electronic telephone exchanges, completing a basic design by about 1950, which led on to the Highgate Wood Telephone Exchange. He was also involved in the development of ERNIE.[12] In 1964, he became head of the advanced development at Standard Telephones and Cables Ltd.,[13] where he continued to develop electronic telephone switching including a pulse amplitude modulation exchange, retiring in 1969.[14]

In 1976, he published Introduction to Exchange Systems, a book on the engineering principles of telephone exchanges.[15]

In 1977 Flowers was made an honorary Doctor of Science by Newcastle University.[16]

In 1980 he was the first winner of the Martlesham Medal in recognition of his achievements in computing.[17]

In 1993, he received a certificate from Hendon College, having completed a basic course in information processing on a personal computer.[18]

Flowers died in 1998 aged 92, leaving a wife and two sons.[1] He is commemorated at the Post Office Research Station site, which became a housing development, with the main building converted into a block of flats and an access road called Flowers Close. He was honoured by London Borough of Tower Hamlets, where he was born. An Information and Communications Technology (ICT) centre for young people, the Tommy Flowers Centre, opened there in November 2010.[19] The centre has closed but the building is now the Tommy Flowers Centre, part of the Tower Hamlets Pupil Referral Unit.

In September 2012, his wartime diary was put on display at Bletchley Park.[20] A road in Kesgrave, near the current BT Research Laboratories, is named Tommy Flowers Drive.[21]

On Thursday 12 December 2013, 70 years after he created Colossus, his legacy was honoured with a memorial commissioned by BT, successor to Post Office Telephones. The life-size bronze bust, designed by James Butler, was unveiled by Trevor Baylis at Adastral Park, BT's research and development centre in Martlesham Heath, near Ipswich, Suffolk. BT also began a computer science scholarship and award in his name.[22]

On Thursday 29 September 2016 BT opened the Tommy Flowers Institute for ICT training at Adastral Park to support the development of postgraduates transferring into industry. The institute focuses on bringing ICT-sector organisations together with academic researchers to solve some of the challenges facing UK businesses, exploring areas such as cybersecurity, big data, autonomics and converged networks. The launch event was attended by professors from Cambridge, Oxford, East Anglia, Essex, Imperial, UCL, Southampton, Surrey, and Lancaster as well as representatives from the National Physical Laboratory, Huawei, Ericsson, CISCO, ARM and ADVA [23]

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Thomas Flowers Biography". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. 2008. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/71253.

- ↑ Randell 2006, p. 144

- ↑ see interview of Flowers in PBS Nova "Decoding Nazi Secrets" 2015

- ↑ McKay, Sinclair The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010, Aurum Press, London) pp266-8 ISBN 978 1 84513539 3

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 36035. pp. 2491–2495. 4 June 1943. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- ↑ Tommy Flowers MBE Bletchleypark.org

- ↑ Flowers 2006, p. 81

- ↑ ['Station X' http://ftvdb.bfi.org.uk/sift/series/30779]

- ↑ Howard, Campaigne (1983-07-03). "The Design of Colossus: Thomas H. Flowers". Annals of the History of Computing. 5 (3): 239. doi:10.1109/MAHC.1983.10079. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- ↑ Transcript of 1999 Nova television program "Decoding Nazi Secrets"

- ↑ Tommy Flowers: Technical Innovator (obituary), BBC, 2003.

- ↑ Inside Out: Premium Bonds, BBC

- ↑ Andrews, Jork (Autumn 2012). "The Sacking of Tommy Flowers". Resurrection: The Bulletin of the Computer Conservation Society. 59. pp. 29–34. ISSN 0958-7403.

- ↑ Randell, Brian. "A History of Computing in the Twentieth Century: The Colossus" (PDF). Newcastle University, UK.

- ↑ Flowers, T. H. (1976). Introduction to Exchange Systems. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-01865-1.

- ↑ http://www.ncl.ac.uk/computing/research/hon/flowers/

- ↑ Bray, John (2002). Innovation and the communications revolution. IEE. p. 193. ISBN 0852962185.

- ↑ Code-Breakers: Bletchley Park's Lost Heroes, BBC, 29 October 2011.

- ↑ "Official Launch of The Tommy Flowers City Learning Centre". Tower Hamlets CLC. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ↑ Wartime diary helps to tell Colossus story, BBC, 7 September 2012.

- ↑ http://www.kesgravetowncouncil.org.uk/roadnames.html#sep09

- ↑ BT remembers Tommy Flowers

- ↑ http://home.bt.com/tech-gadgets/tech-news/tommy-flowers-institute-for-ict-launched-at-bts-adastral-park-11364101636384

Bibliography

- Copeland, B. Jack, ed. (2006). Colossus: The Secrets of Bletchley Park's Codebreaking Computers. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-284055-4

- Flowers, Thomas H. (2006). "D-Day at Bletchley Park" in Copeland 2006, pp. 78–83

- Randell, Brian (2006). "Of Men and Machines" in Copeland 2006, pp. 141–149

External links

- The Design of Colossus, Thomas H. Flowers

- Quotes about Flowers

- Tommy Flowers talking about Colossus

- Code-Breakers: Bletchley Park's Lost Heroes

- Imperial War Museum Interview