To Live (1994 film)

| To Live | |

|---|---|

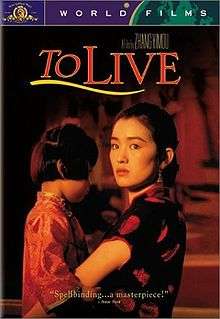

To Live DVD cover | |

| Traditional | 活著 |

| Simplified | 活着 |

| Mandarin | Huózhe |

| Literally | alive / to be alive |

| Directed by | Zhang Yimou |

| Produced by |

Fu-Sheng Chiu Funhong Kow Christophe Tseng |

| Written by | Lu Wei |

| Based on |

To Live by Yu Hua |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Zhao Jiping |

| Cinematography | Lü Yue |

| Edited by | Du Yuan |

| Distributed by | The Samuel Goldwyn Company |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 132 minutes |

| Country | China |

| Language | Mandarin |

To Live, also titled Lifetimes in some English versions,[1] is a Chinese film directed by Zhang Yimou in 1994, starring Ge You, Gong Li, and produced by the Shanghai Film Studio and ERA International. It is based on the novel of the same name by Yu Hua. Having achieved international success with his previous films (Ju Dou and Raise the Red Lantern), director Zhang Yimou's To Live came with high expectations. It is the first Chinese film that had its foreign distribution rights pre-sold.[2]

The film was banned in mainland China by the Chinese State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television[3] due to its critical portrayal of various policies and campaigns of the Communist government.

To Live was screened at the 1994 New York Film Festival before eventually receiving a limited release in the United States on November 18, 1994.[4]

Development

Zhang Yimou originally intended to adapt Mistake at River's Edge, a thriller written by Yu Hua. Yu gave Zhang a set of all of the works that had been published at that point so Zhang could understand his works. Zhang said that he began reading To Live, one of the works, and was unable to stop reading it. Zhang met Yu to discuss the script for Mistake at River's Edge, but they kept bringing up To Live. The two decided to have To Live adapted instead.[1]

Plot summary

In the 1940s. Xu Fugui (Ge You) is a rich man's son and compulsive gambler, who loses his family property to a man named Long'er. His behaviour also causes his long-suffering wife Jiazhen (Gong Li) to leave him, along with their daughter, Fengxia and their unborn son, Youqing.

Fugui eventually reunites with his wife and children, but is forced to start a shadow puppet troupe with a partner named Chunsheng. The Chinese Civil War is occurring at the time, and both Fugui and Chunsheng are conscripted into the Kuomintang during a performance. Midway through the war, the two are captured by the revolutionary army and serve by performing their shadow puppet routine for the revolutionaries. Eventually Fugui is able to return home, only to find out that due to a week-long fever, Fengxia has become mute and partially deaf.

Soon after his return, Fugui learns that Long'er did not want to donate any of his wealth to the "people's government", and so Long'er decided to burn all of his property. No one helps put out the fire because Long'er was a gentry. He is eventually put on trial and is sentenced to execution. As Long'er is pulled away, he recognizes Fugui in the crowd, and tries to talk to him as he is dragged towards the execution grounds. Fugui is filled with fear and runs into an alleyway before hearing five gunshots. He runs home to tell Jiazhen what has happened, and they quickly pull out the certificate stating that Fugui served in the revolutionary army. Fugui assures his wife that they are no longer gentries and will not be killed.

The story moves forward a decade into the future, to the time of the Great Leap Forward. The local town chief enlists everyone to donate all scrap iron to the national drive to produce steel and make weaponry for retaking Taiwan. As an entertainer, Fugui performs for the entire town nightly, and is very smug about his singing abilities.

Soon after, some boys begin picking on Fengxia. Youqing decides to get back at one of the boys by dumping spicy noodles on his head during a communal lunch. Fugui is furious, but Jiazhen stops him and tells him why Youqing acted the way he did. Fugui realizes the love his children have for each other.

The children are exhausted from the hard labor they are doing in the town and try to sleep whenever they can. They eventually get a break during the festivities for meeting the scrap metal quota. The entire village eats dumplings in celebration. In the midst of the family eating, schoolmates of Youqing call for him to come prepare for the District Chief. Jiazhen tries to make Fugui let him sleep but eventually relents and packs her son twenty dumplings for lunch. Fugui carries his son to the school, and tells him to heat the dumplings before eating them, as he will get sick if he eats cold dumplings. He must listen to his father to have a good life.

Later on in the day, the older men and students rush to tell Fugui that his son has been killed by the District Chief. He was sleeping on the other side of a wall that the Chief's Jeep was on, and the car ran into the wall, injuring the Chief and crushing Youqing. Jiazhen, in hysterics, is forbidden to see her son's dead body, and Fugui screams at his son to wake up. Fengxia is silent in the background.

The District Chief visits the family at the grave, only to be revealed as Chunsheng. His attempts to apologize and compensate the family are rejected, particularly by Jiazhen, who tells him he owes her family a life. He returns to his Jeep in a haze, only to see his guard beating Fengxia for breaking the Jeep's windows. He tells him to stop, and walks home.

The story moves forward again another decade, to the Cultural Revolution. The village chief advises Fugui's family to burn their puppet drama props, which have been deemed as counter-revolutionary. Fengxia carries out the act, and is oblivious to the Chief's real reason for coming: to discuss a suitor for her. Fengxia is now grown up and her family arranges for her to meet Wan Erxi, a local leader of the Red Guards. Erxi, a man crippled by a workplace accident, fixes her parent's roof and paints depictions of Mao Zedong on their walls with his workmates. He proves to be a kind, gentle man; he and Fengxia fall in love and marry, and she soon becomes pregnant.

Chunsheng, still in the government, has been branded a reactionary and a capitalist. He visits immediately after the wedding to ask for Jiazhen's forgiveness, and to tell them his wife has committed suicide and he intends to as well. He has come to give them all his money. Jiazhen refuses to take it. However, they urge him to not commit suicide by telling him he still owes them a life.

Months later, during Fengxia's childbirth, her parents and husband accompany her to the county hospital. All doctors have been sent to do hard labor for being over educated, and the students are left as the only ones in charge. Wan Erxi manages to find a doctor to oversee the birth, removing him from confinement, but he is very weak from starvation. Fugui purchases seven steamed buns (mantou) for him and the family decides to name the son Mantou, after the buns. However, Fengxia begins to hemorrhage, and the nurses panic, admitting that they do not know what to do. The family and nurses seek the advice of the doctor, but find that he has overeaten and is semiconscious. The family is helpless, and Fengxia dies from hypovolemia (blood loss). The point is made that the doctor ate 7 buns, but that by drinking too much water at the same time, each bun expanded to the size of 7 buns: therefore Fengxia's death is a result of the doctor's having the equivalent of 49 buns in his belly.

The movie ends six years later, with the family now consisting of Fugui, Jiazhen, their son-in-law Erxi, and grandson Mantou. The family visits the graves of Youqing and Fengxia, where Jiazhen, as per tradition, leaves dumplings for her son. Erxi buys a box full of young chicks for his son, which they decide to keep in the chest formerly used for the shadow puppet props. When Mantou inquires how long it will take for the chicks to grow up, Fugui's response is a more tempered version of something he said earlier in the film. However, in spite of all of his personal hardships, he expresses optimism for his grandson's future, and the film ends with his statement, "and life will get better and better" as the whole family sits down to eat.[5]

Characters

- Xu Fugui (t 徐福貴, s 徐福贵, Xú Fúguì, lit. "Lucky & Rich")

- Fugui has a sense of political idealism that is not present in the original novel. By the end of the film he loses this sense of idealism.[1]

- Jiazhen (家珍, Jiāzhēn, lit. "Precious Family"), his wife

- Xu Fengxia (t 徐凤霞, s 徐凤霞, Xú Fèngxiá, lit. "Phoenix & Rosy Clouds"), his daughter

- Xu Youqing (t 徐有慶, s 徐有庆, Xú Yǒuqìng, lit. "Full of Celebration"), his son

- Wan Erxi (t 萬二喜, s 万二喜, Wàn Èrxǐ, lit. "Double Happiness"), Fengxia's husband

- Long'er (t 龍二, s 龙二, Lóng'èr lit. "Dragon the Second")

- Chunsheng (春生, Chūnshēng, lit. "Spring-born")

Differences

The film changes the setting from rural southern China to a small city in northern China. The film added the element of Fugui's shadow puppetry. The second narrator and the ox are not present in the film.[1] Michael Berry, the editor of an English edition of the novel To Live, said that the novel has a "darker and more existential" message and a "much more brutal" reality and social critique, while the film renders Communist ideals to be failed, but offers a capitalist China as having promise.[1] Berry says that the film "allows more room for the hand of fate to hold sway."[1]

Awards and nominations

| Awards | Year | Category | Result | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannes Film Festival[6] | 1994 | Grand Prix | Won | with Burnt by the Sun |

| Prize of the Ecumenical Jury | Won | with Burnt by the Sun | ||

| Best Actor (Ge You) |

Won | |||

| Palme d'Or | Nominated | |||

| Golden Globe Award[7] | 1994 | Best Foreign Language Film | Nominated | |

| National Board of Review[8] | 1994 | Best Foreign Language Film | Top 5 | with four other films |

| National Society of Film Critics Award[9] | 1995 | Best Foreign Language Film | Runner-up | |

| BAFTA Award[10] | 1995 | Best Film Not in the English Language | Won | |

| Chlotrudis Award[11] | 1995 | Best Actress (Gong Li) |

Nominated | |

| Dallas-Fort Worth Film Critics Association Award[9] | 1995 | Best Foreign Film | Runner-up |

- Accolades

- Time Out 100 best Chinese Mainland Films – #8[12]

- Included in The New York Times's list of The Best 1000 Movies Ever Made in 2004[13]

- Included in CNN's list of 18 Best Asian Movies of All Time in 2008[14]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Yu, Hua. Editor: Michael Berry. To Live. Random House Digital, Inc., 2003. 242. ISBN 978-1-4000-3186-3.

- ↑ Klapwald, Thea (1994-04-27). "On the Set with Zhang Yimou". The International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ↑ Zhang Yimou. Frances K. Gateward, Yimou Zhang, University Press of Mississippi, 2001, pp. 63-4.

- ↑ James, Caryn (1994-11-18). "Film Review; Zhang Yimou's 'To Live'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0110081/synopsis

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes – Huozhe". Cannes Film Festival. Archived from the original on 22 August 2011.

- ↑ "Winners & Nominees 1994". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on 29 February 2016.

- ↑ "1994 Archives". National Board of Review. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Huo zhe – Awards". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ↑ "BAFTA Awards (1995)". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015.

- ↑ "Li Gong". TV.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ↑ "100 best Chinese Mainland Films (top 10)". Time Out. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ↑ "The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ↑ Mackay, Mairi (23 September 2008). "Pick the best Asian films of all time". CNN. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

Further reading

- Giskin, Howard and Bettye S. Walsh. An Introduction to Chinese Culture Through the Family. SUNY Press, 2001. ISBN 0-7914-5048-1, ISBN 978-0-7914-5048-2.

- Xiao, Zhiwei. "Reviewed work(s): The Wooden Man's Bride by Ying-Hsiang Wang; Yu Shi; Li Xudong; Huang Jianxin; Yang Zhengguang Farewell My Concubine by Feng Hsu; Chen Kaige; Lillian Lee; Wei Lu The Blue Kite by Tian Zhuangzhuang To Live by Zhang Yimou; Yu Hua; Wei Lu; Fusheng Chin; Funhong Kow; Christophe Tseng." The American Historical Review. Vol. 100, No. 4 (Oct., 1995), pp. 1212–1215

External links

- To Live at the Internet Movie Database

- To Live at AllMovie

- To Live at Rotten Tomatoes