Tirukkuṛaḷ

Statue of Thiruvalluvar at Kanyakumari | |

| Author | Thiruvalluvar |

|---|---|

| Original title | Muppaal |

| Working title | Thirukkural |

| Country | India |

| Language | Old Tamil |

| Series | Patiṉeṇkīḻkaṇakku |

| Subject | Ethics and morality |

| Genre | Poetry |

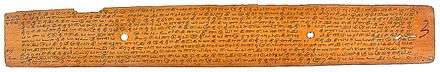

| Published | Palm-leaf manuscript of the Tamil Sangam era (possibly between 3rd and 1st centuries BCE) |

Publication date | 1812 (first known printed edition) |

Published in English | 1840 |

| Tamil Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The Tirukkural or Thirukkural (Tamil Name: திருக்குறள்), or shortly the Kural, is a classic Tamil sangam literature consisting of 1330 couplets or kurals, dealing with the everyday virtues of an individual.[1][2] Considered one of the greatest works ever written on ethics and morality, it is known for its universality and non-denominational nature.[3] It was authored by Thiruvalluvar.

Considered as chef d'oeuvre of both Indian and world literature,[4] the Tirukkural is one of the most important works in the Tamil language. This is reflected in some of the other names by which the text is given by, such as Tamiḻ maṟai (Tamil veda), Poyyāmoḻi (words that never fail), and Deiva nūl (divine text).[5] Translated to about 82 global languages, Tirukkural is the most widely translated non-religious work in the world.[6] The work is dated to sometime between the third and first centuries BCE and is considered to precede Silappatikaram (1st century CE) and Manimekalai (between 1st and 5th centuries CE), since they both acknowledge the Kural text.[7]

Etymology

Tirukkural was originally known as 'Muppaal', meaning three-sectioned book, since it contained three sections, viz., 'Aram', 'Porul' and 'Inbam'. Thiru is a term denoting divine respect, literally meaning holy or sacred. Kural is a very short Tamil poetic form consisting of two lines, the first line consisting of four words (known as cirs) and the second line consisting of three, which should also conform to the grammar of Venpa, and is one of the most important forms of classical Tamil language poetry. Since the work was written in this poetic form, it came to be known as 'Tirukkural', meaning 'sacred couplets'.

Other names

Originally mentioned as 'Muppaal' by its author, Tirukkural has been known by many names in various literature works:[8]

- முப்பால் (Muppāl) – "The Three-Chaptered" or "The Three-Sectioned" (Original name given by Thiruvalluvar)

- பொய்யாமொழி (Poyyāmoḻi) – "Statements Devoid of Untruth"

- உத்தரவேதம் (Uttharavedham) – "Northern Veda"

- வாயுறை வாழ்த்து (Vāyurai Vāḻttu) – "Truthful Utterances"

- தெய்வநூல் (Teyvanūl) – "The Holy Book"

- பொதுமறை (Potumaṟai) – "The Universal Veda" or "Book for All"

- தமிழ்மறை (Tamiḻ Maṟai) – "The Tamil Veda"

- முப்பானூல் (Muppāṉūl) – "The Three-Sectioned Book"

- ஈரடி நூல் (Iradi ṉūl) – "The Two-Lined Book"

- திருவள்ளுவம் (Thiruvalluvam) – "Thiruvalluvarism" or "The Work of Thiruvalluvar"

Author

There are claims and counter claims as to the authorship of the book and to the exact number of couplets written by Thiruvalluvar. The first instance of the author's name mentioned as Thiruvalluvar is found to be several centuries later in a song of praise called the Garland of Thiruvalluvar in Thiruvalluva Malai.[9]

Thiruvalluvar is thought to have belonged to either Jainism or Hinduism. This can be observed in his treatment of the concept of ahimsa or non-violence, which is the principal concept of both religions. Valluvar's treatment of the chapters on vegetarianism and non-killing reflects the Jain precepts, where these are stringently enforced.[8] The three parts that the Tirukkural is divided into, namely, aram (virtue), porul (wealth) and inbam (love), aiming at attaining veedu (ultimate salvation), follow, respectively, the four foundations of Hinduism, namely, dharma, artha, kama and moksha. The Vaishnavite beliefs of Valluvar are bolstered in his mentioning of God Vishnu in couplets 610 and 1103 and Goddess Lakshmi in couplets 167, 408, 519, 565, 568, 616, and 617. Other Hindu beliefs of Valluvar found in the book include previous birth and re-birth, seven births, and some ancient Indian astrological concepts, among others.[10] Despite using these contemporary religious concepts of his time, Valluvar has limited the usage of these terms to a metaphorical sense to explicate the fundamental virtues and ethics, without enforcing any of these religious beliefs in practice. This, chiefly, has made the treatise earn the title "Ulaga Podhu Marai" (the universal scripture).[10]

There is also the recent claim by Kanyakumari Historical and Cultural Research Centre (KHCRC) that Valluvar was a king who ruled Valluvanadu in the hilly tracts of the Kanyakumari district of Tamil Nadu.[11]

Structure of the book

The Tirukkural is structured into 133 chapters, each containing 10 couplets (or kurals), for a total of 1330 couplets.[12] The 133 chapters are grouped into three sections:.[12][13]

- Aṟam (Tamil: அறத்துப்பால், Aṟattuppāl ?) (Dharma) dealing with virtue (Chapters 1-38)

- Poruḷ (Tamil: பொருட்பால், Poruṭpāl ?) (Artha) dealing with wealth or polity (Chapters 39-108)

- Inbam (Tamil: காமத்துப்பால், Kāmattuppāl ?) (Kama) dealing with love (Chapters 109-133)

Each kural or couplet contains exactly seven words, known as cirs, with four cirs on the first line and three on the second. A cir is a single or a combination of more than one Tamil word. For example, Thirukkural is a cir formed by combining the two words thiru and kuṛaḷ. The section Aram contains 380 verses, Porul has 700 and Inbam has 250.[12]

The overall organisation of the Kural text is based on seven ideals prescribed for a commoner besides observations of love.[11]

- 40 couplets on God, rain, ascetics, and virtue

- 200 couplets on domestic virtue

- 140 couplets on higher virtue based on grace, benevolence and compassion

- 250 couplets on royalty

- 100 couplets on ministers of state

- 220 couplets on essential requirements of administration

- 130 couplets on morality, both positive and negative

- 250 couplets on human love and passion

- Section I—Virtue (அறத்துப்பால் Aṟattuppāl)—38 chapters

- Chapter 1. The Praise of God (கடவுள் வாழ்த்து kaṭavuḷ vāḻttu): Couplets 1–10

- Chapter 2. The Excellence of Rain (வான் சிறப்பு vāṉ ciṟappu): 11–20

- Chapter 3. The Greatness of Ascetics (நீத்தார் பெருமை nīttār perumai): 21–30

- Chapter 4. Assertion of the Strength of Virtue (அறன் வலியுறுத்தல் aṟaṉ valiyuṟuttal): 31–40

- Chapter 5. Domestic Life (இல்வாழ்க்கை ilvāḻkkai): 41–50

- Chapter 6. The Goodness of the Help to Domestic Life (வாழ்க்கைத்துணை நலம் vāḻkkaittuṇai nalam): 51–60

- Chapter 7. The Obtaining of Sons (புதல்வரைப் பெறுதல் putalvaraip peṟutal): 61–70

- Chapter 8. The Possession of Love (அன்புடைமை aṉpuṭaimai): 71–80

- Chapter 9. Cherishing Guests (விருந்தோம்பல் viruntōmpal): 81–90

- Chapter 10. The Utterance of Pleasant Words (இனியவை கூறல் iṉiyavai kūṟal): 91–100

- Chapter 11. The Knowledge of Benefits Conferred: Gratitude (செய்ந்நன்றி அறிதல் ceynnaṉṟi aṟital): 101–110

- Chapter 12. Impartiality (நடுவு நிலைமை naṭuvu nilaimai): 111–120

- Chapter 13. The Possession of Self-restraint (அடக்கமுடைமை aṭakkamuṭaimai): 121–130

- Chapter 14. The Possession of Decorum (ஒழுக்கமுடைமை oḻukkamuṭaimai): 131–140

- Chapter 15. Not coveting another's Wife (பிறனில் விழையாமை piṟaṉil viḻaiyāmai): 141–150

- Chapter 16. The Possession of Patience, Forbearance (பொறையுடைமை poṟaiyuṭaimai): 151–160

- Chapter 17. Not Envying (அழுக்காறாமை aḻukkāṟāmai): 161–170

- Chapter 18. Not Coveting (வெஃகாமை veḵkāmai): 171–180

- Chapter 19. Not Backbiting (புறங்கூறாமை puṟaṅkūṟāmai): 181–190

- Chapter 20. The Not Speaking Profitless Words (பயனில சொல்லாமை payaṉila collāmai): 191–200

- Chapter 21. Dread of Evil Deeds (தீவினையச்சம் tīviṉaiyaccam): 201–210

- Chapter 22. The knowledge of what is Befitting a Man's Position (ஒப்புரவறிதல் oppuravaṟital): 211–220

- Chapter 23. Giving (ஈகை īkai): 221–230

- Chapter 24. Renown (புகழ் pukaḻ): 231–240

- Chapter 25. The Possession of Benevolence (அருளுடைமை aruḷuṭaimai): 241–250

- Chapter 26. The Renunciation of Flesh (புலான் மறுத்தல் pulāṉmaṟuttal): 251–260

- Chapter 27. Penance (தவம் tavam): 261–270

- Chapter 28. Inconsistent Conduct (கூடாவொழுக்கம் kūṭāvoḻukkam): 271–280

- Chapter 29. The Absence of Fraud (கள்ளாமை kaḷḷāmai): 281–290

- Chapter 30. Veracity (வாய்மை vāymai): 291–300

- Chapter 31. The not being Angry (வெகுளாமை vekuḷāmai): 301–310

- Chapter 32. Not doing Evil (இனனா செய்யாமை iṉṉāceyyāmai): 311–320

- Chapter 33. Not killing (கொல்லாமை kollāmai): 321–330

- Chapter 34. Instability (நிலையாமை nilaiyāmai): 331–340

- Chapter 35. Renunciation (துறவு tuṟavu): 341–350

- Chapter 36. Knowledge of the True (மெய்யுணர்தல் meyyuṇartal): 351–360

- Chapter 37. The Extirpation of Desire (அவாவறுத்தல் avāvaṟuttal): 361–370

- Chapter 38. Fate (ஊழ் ūḻ): 371–380

- Section II—Wealth (பொருட்பால் Poruṭpāl)—70 chapters

- Chapter 39. The Greatness of a King (இறைமாட்சி iṟaimāṭci): 381–390

- Chapter 40. Learning (கல்வி kalvi): 391–400

- Chapter 41. Ignorance (கல்லாமை kallāmai): 401–410

- Chapter 42. Hearing (கேள்வி kēḷvi): 411–420

- Chapter 43. The Possession of Knowledge (அறிவுடைமை aṟivuṭaimai): 421–430

- Chapter 44. The Correction of Faults (குற்றங்கடிதல் kuṟṟaṅkaṭital): 431–440

- Chapter 45. Seeking the Aid of Great Men (பெரியாரைத் துணைக்கோடல் periyārait tuṇaikkōṭal): 441–450

- Chapter 46. Avoiding mean Associations (சிற்றினஞ்சேராமை ciṟṟiṉañcērāmai): 451–460

- Chapter 47. Acting after due Consideration (தெரிந்து செயல்வகை terintuceyalvakai): 461–470

- Chapter 48. The Knowledge of Power (வலியறிதல் valiyaṟital): 471–480

- Chapter 49. Knowing the fitting Time (காலமறிதல் kālamaṟital): 481–490

- Chapter 50. Knowing the Place (இடனறிதல் iṭaṉaṟital): 491–500

- Chapter 51. Selection and Confidence (தெரிந்து தெளிதல் terintuteḷital): 501–510

- Chapter 52. Selection and Employment (தெரிந்து வினையாடல் terintuviṉaiyāṭal): 511–520

- Chapter 53. Cherishing one's Kindred (சுற்றந்தளால் cuṟṟantaḻāl): 521–530

- Chapter 54. Unforgetfulness (பொச்சாவாமை poccāvāmai): 531–540

- Chapter 55. The Right Sceptre (செங்கோன்மை ceṅkōṉmai): 541–550

- Chapter 56. The Cruel Sceptre (கொடுங்கோன்மை koṭuṅkōṉmai): 551–560

- Chapter 57. Absence of Terrorism (வெருவந்த செய்யாமை veruvantaceyyāmai): 561–570

- Chapter 58. Benignity (கண்ணோட்டம் kaṇṇōṭṭam): 571–580

- Chapter 59. Detectives (ஒற்றாடல் oṟṟāṭal): 581–590

- Chapter 60. Energy (ஊக்கமுடைமை ūkkamuṭaimai): 591–600

- Chapter 61. Unsluggishness (மடியின்மை maṭiyiṉmai): 601–610

- Chapter 62. Manly Effort (ஆள்வினையுடைமை āḷviṉaiyuṭaimai): 611–620

- Chapter 63. Hopefulness in Trouble (இடுக்கண் அழியாமை iṭukkaṇ aḻiyāmai): 621–630

- Chapter 64. The Office of Minister of State (அமைச்சு amaiccu): 631–640

- Chapter 65. Power in Speech (சொல்வன்மை colvaṉmai): 641–650

- Chapter 66. Purity in Action (வினைத்தூய்மை viṉaittūymai): 651–660

- Chapter 67. Power in Action (வினைத்திட்பம் viṉaittiṭpam): 661–670

- Chapter 68. The Method of Acting (வினை செயல்வகை viṉaiceyalvakai): 671–680

- Chapter 69. The Envoy (தூது tūtu): 681–690

- Chapter 70. Conduct in the Presence of the King (மன்னரைச் சேர்ந்தொழுதல் maṉṉaraic cērntoḻutal): 691–700

- Chapter 71. The Knowledge of Indications (குறிப்பறிதல் kuṟippaṟital): 701–710

- Chapter 72. The Knowledge of the Council Chamber (அவையறிதல் avaiyaṟital): 711–720

- Chapter 73. Not to dread the Council (அவையஞ்சாமை avaiyañcāmai): 721–730

- Chapter 74. The Land (நாடு nāṭu): 731–740

- Chapter 75. The Fortification (அரண் araṇ): 741–750

- Chapter 76. Way of Accumulating Wealth (பொருள் செயல்வகை poruḷceyalvakai): 751–760

- Chapter 77. The Excellence of an Army (படைமாட்சி paṭaimāṭci): 761–770

- Chapter 78. Military Spirit (படைச்செருக்கு paṭaiccerukku): 771–780

- Chapter 79. Friendship (நட்பு naṭpu): 781–790

- Chapter 80. Investigation in forming Friendships (நட்பாராய்தல் naṭpārāytal): 791–800

- Chapter 81. Familiarity (பழைமை paḻaimai): 801–810

- Chapter 82. Evil Friendship (தீ நட்பு tī naṭpu): 811–820

- Chapter 83. Unreal Friendship (கூடா நட்பு kūṭānaṭpu): 821–830

- Chapter 84. Folly (பேதைமை pētaimai): 831–840

- Chapter 85. Ignorance (புல்லறிவாண்மை pullaṟivāṇmai): 841–850

- Chapter 86. Hostility (இகல் ikal): 851–860

- Chapter 87. The Might of Hatred (பகை மாட்சி pakaimāṭci): 861–870

- Chapter 88. Knowing the Quality of Hate (பகைத்திறந்தெரிதல் pakaittiṟanterital): 871–880

- Chapter 89. Enmity Within (உட்பகை uṭpakai): 881–890

- Chapter 90. Not Offending the Great (பெரியாரைப் பிழையாமை periyāraip piḻaiyāmai): 891–900

- Chapter 91. Being led by Women (பெண்வழிச் சேறல் peṇvaḻiccēṟal): 901–910

- Chapter 92. Wanton Women (வரைவின் மகளிர் varaiviṉmakaḷir): 911–920

- Chapter 93. Not Drinking Palm-Wine (கள்ளுண்ணாமை kaḷḷuṇṇāmai): 921–930

- Chapter 94. Gaming (Gambling) (சூது cūtu): 931–940

- Chapter 95. Medicine (மருந்து maruntu): 941–950

- Chapter 96. Nobility (குடிமை kuṭimai): 951–960

- Chapter 97. Honour (மானம் māṉam): 961–970

- Chapter 98. Greatness (பெருமை perumai): 971–980

- Chapter 99. Perfectness (சான்றாண்மை cāṉṟāṇmai): 981–990

- Chapter 100. Courtesy (பண்புடைமை paṇpuṭaimai): 991–1000

- Chapter 101. Wealth without Benefaction (நன்றியில் செல்வம் naṉṟiyilcelvam): 1001–1010

- Chapter 102. Shame (நாணுடைமை nāṇuṭaimai): 1011–1020

- Chapter 103. The Way of Maintaining the Family (குடிசெயல்வகை kuṭiceyalvakai): 1021–1030

- Chapter 104. Agriculture (உழவு uḻavu): 1031–1040

- Chapter 105. Poverty (நல்குரவு nalkuravu): 1041–1050

- Chapter 106. Mendicancy (இரவு iravu): 1051–1060

- Chapter 107. The Dread of Mendicancy (இரவச்சம் iravaccam): 1061–1070

- Chapter 108. Baseness (கயமை kayamai): 1071–1080

- Section III—Love (காமத்துப்பால் kāmattuppāl or இன்பத்துப்பால் iṉpattuppāl)—25 chapters

- Chapter 109. Mental Disturbance Caused by the Beauty of the Princess (தகையணங்குறுத்தல் takaiyaṇaṅkuṟuttal): 1081–1090

- Chapter 110. Recognition of the Signs (of Mutual Love) (குறிப்பறிதல் kuṟippaṟital): 1091–1100

- Chapter 111. Rejoicing in the Embrace (புணர்ச்சி மகிழ்தல் puṇarccimakiḻtal): 1101–1110

- Chapter 112. The Praise of Her Beauty (நலம் புனைந்துரைத்தல் nalampuṉainturaittal): 1111–1120

- Chapter 113. Declaration of Love's Special Excellence (காதற் சிறப்புரைத்தல் kātaṟciṟappuraittal): 1121–1130

- Chapter 114. The Abandonment of Reserve (நாணுத் துறவுரைத்தல் nāṇuttuṟavuraittal): 1131–1140

- Chapter 115. The Announcement of the Rumour (அலரறிவுறுத்தல் alaraṟivuṟuttal): 1141–1150

- Chapter 116. Separation Unendurable (பிரிவாற்றாமை pirivāṟṟāmai): 1151–1160

- Chapter 117. Complainings (படர் மெலிந்திரங்கல் paṭarmelintiraṅkal): 1161–1170

- Chapter 118. Eyes Consumed with Grief (கண்விதுப்பழிதல் kaṇvituppaḻital): 1171–1180

- Chapter 119. The Pallid Hue (பசப்பறு பருவரல் pacappaṟuparuvaral): 1181–1190

- Chapter 120. The Solitary Anguish (தனிப்படர் மிகுதி taṉippaṭarmikuti): 1191–1200

- Chapter 121. Sad Memories (நினைந்தவர் புலம்பல் niṉaintavarpulampal): 1201–1210

- Chapter 122. The Visions of the Night (கனவுநிலையுரைத்தல் kaṉavunilaiyuraittal): 1211–1220

- Chapter 123. Lamentations at Eventide (பொழுதுகண்டிரங்கல் poḻutukaṇṭiraṅkal): 1221–1230

- Chapter 124. Wasting Away (உறுப்பு நலனழிதல் uṟuppunalaṉaḻital): 1231–1240

- Chapter 125. Soliloquy (நெஞ்சொடு கிளத்தல் neñcoṭukiḷattal): 1241–1250

- Chapter 126. Reserve Overcome (நிறையழிதல் niṟaiyaḻital): 1251–1260

- Chapter 127. Mutual Desire (அவர்வயின் விதும்பல் avarvayiṉvitumpal): 1261–1270

- Chapter 128. The Reading of the Signs (குறிப்பறிவுறுத்தல் kuṟippaṟivuṟuttal): 1271–1280

- Chapter 129. Desire for Reunion (புணர்ச்சி விதும்பல் puṇarccivitumpal): 1281–1290

- Chapter 130. Expostulation with Oneself (நெஞ்சொடு புலத்தல் neñcoṭupulattal): 1291–1300

- Chapter 131. Pouting (புலவி pulavi): 1301–1310

- Chapter 132. Feigned Anger (புலவி நுணுக்கம் pulavi nuṇukkam): 1311–1320

- Chapter 133. The Pleasures of 'Temporary Variance' (ஊடலுவகை ūṭaluvakai): 1321–1330

Tone of the book

Tirukkural expounds a secular, moral and practical attitude towards life. Unlike religious scriptures, Tirukkural refrains from talking of hopes and promises of the other-worldly life. Rather it speaks of the ways of cultivating one's mind to achieve the other-worldly bliss in the present life itself. By occasionally referring to bliss beyond the worldly life, Valluvar equates what can be achieved in humanly life with what may be attained thereafter.[3]

Universality

The Tirukkural is praised for its universality across the globe. The ancient Tamil poet Avvaiyar observed, "Thiruvalluvar pierced an atom and injected seven seas into it and compressed it into what we have today as Kural."[14] The Russian philosopher Alexander Piatigorsky called it chef d'oeuvre of both Indian and world literature "due not only to the great artistic merits of the work but also to the lofty humane ideas permeating it which are equally precious to the people all over the world, of all periods and countries."[4] G. U. Pope called him "A bard of universal man."[15] According to Albert Schweitzer, "there hardly exists in the literature of the world a collection of maxims in which we find so much of lofty wisdom."[14] Leo Tolstoy was inspired by the concept of non-violence found in the Tirukkural when he read a German version of the book, who in turn instilled the concept in Mahatma Gandhi through his A Letter to a Hindu when young Gandhi sought his guidance.[14] Mahatma Gandhi, who took to studying Tirukkural in prison,[3] called it "a textbook of indispensable authority on moral life" and went on to say, "The maxims of Valluvar have touched my soul. There is none who has given such a treasure of wisdom like him."[14] Sir A. C. Grant said, "Humility, charity and forgiveness of injuries, being Christian qualities, are not described by Aristotle. Now these three are everywhere forcibly inculcated by the Tamil Moralist."[16] E. J. Robinson said that Tirukkural contains all things and there is nothing which it does not contain.[14] Rev. J. Lazarus said, "No Tamil work can ever approach the purity of the Kural. It is a standing repute to modern Tamil."[14] According to K. M. Munshi, "Thirukkural is a treatise par excellence on the art of living."[14] Sri Aurobindo stated, "Thirukkural is gnomic poetry, the greatest in planned conception and force of execution ever written in this kind."[14] Monsieur Ariel, who translated and published the third part of the Kural to French in 1848, called it "a masterpiece of Tamil literature, one of the highest and purest expressions of human thought."[16] According to Rev. Emmons E. White, "Thirukkural is a synthesis of the best moral teachings of the world."[14] Rajaji commented, "It is the gospel of love and a code of soul-luminous life. The whole of human aspiration is epitomized in this immortal book, a book for all ages."[14] Zakir Hussain, former President of India, said, "Thirukkural is a treasure house of worldly knowledge, ethical guidance and spiritual wisdom."[14]

Along with Nalatiyar, another work on ethics and morality from the Sangam period, Tirukkural is praised for its veracity. An age-old Tamil maxim has it that "banyan and acacia maintain oral health; Four and Two maintain moral health," where "Four" and "Two" refer to the quatrains and couplets of Nālaṭiyār and Tirukkural, respectively.

Although it has been widely acknowledged that Thiruvalluvar was of Jain origin and the Tirukkural to its most part was inspired from Jain, Hindu and other ancient Indian philosophies, owing to its universality and non-denominational nature, almost every religious group in India and across the world, including Christianity, has claimed the work for itself. For example, G. U. Pope speaks of the book as an "echo of the 'Sermon on the Mount.'" In the Introduction to his English translation of the Kural, Pope even claims "I cannot feel any hesitation in saying that the Christian Scriptures were among the sources from which the poet derived his inspiration." However, the chapters on the ethics of Vegetarianism (Chapter 26) and non-killing (Chapter 33), which the Kural emphasizes unambiguously unlike other religious texts, suggest that the ethics of the Kural is rather a reflection of the Jaina moral code than of Christian ethics.[8]

Commentaries and translations

Tirukkural is arguably the most reviewed work of all works in Tamil literature, and almost every major writer has written commentaries on it. There have been several commentaries written on the Tirukkural over the centuries. There were at least ten ancient commentaries written by pioneer poets of which only six are available today. The ten commentators include Dharumar, Manakkudavar (11th century CE), Dhaamatthar, Nakkar, Paridhi, Thirumalaiyar, Mallar, Kaliperumal or Pari Perumal (11th century CE), Kaalingar (12th century CE), and Parimelazhagar. The pioneer commentators are Manakkudavur and Parimelazhagar (13th century CE).[10][3] In 1935, V. O. Chidambaram Pillai had written commentary on the first part of the Tirukkural (virtue) and was published in a different title, although it was only in 2008 that the complete work of his commentary on the Tirukkural was published. Other Tamil commentaries include those by Thiru Vi Ka, Bharathidasan, M. Varadarajan, Namakkal kavignar, Devaneya Pavanar, M. Karunanithi, and Solomon Pappaiah. Almost every celebrated writer has written a commentary on the text.

Barring the Bible and the Quran, the Kural is considered the most translated work in the world. It has been translated to over 80 world languages.[6]

The Christian missionaries who came to India during the British era, inspired by the similarities of the Christian ideals found in the Kural, started translating the text into various European languages.[17] The Latin translation of the Tirukkural, the first of the translations into European languages, was made by Constantius Joseph Beschi in 1730. However, he translated only the first two parts, viz., virtue and wealth, leaving out the section on love assuming that it would be inappropriate for a Christian missionary to do so. The first French translation was brought about by an unknown author by about 1767 that went unnoticed. The first available French version was by Monsieur Ariel in 1848. Again, he did not translate the whole work but only parts of it. The first German translation was made by Dr. Karl Graul, who published it in 1856 both at London and Leipzig. Graul's translation was unfortunately incomplete due to his premature death.[17] The first, and incomplete, English translation was made by Francis Whyte Ellis, who translated only 120 couplets—69 of them in verse and 51 in prose.[18][19][20][21] W. H. Drew translated the first two parts in prose in 1840 and 1852, respectively. It contained the original Tamil text of the Kural, Parimelazhagar's commentary, Ramanuja Kavirayar's amplification of the commentary and Drew's English prose translation. However, Drew was able to translate only 630 couplets, and the remaining were made by John Lazarus, a native missionary. Like Beschi, Drew did not translate the part on love.[17] The first complete English translation of the Kural was the one by George Uglow Pope in 1886, which brought the Tirukkural to the western world.[22] By the turn of the twenty-first century, the Tirukkural had already been translated to more than 37[23] languages across the world by various authors. By the end of the twentieth century, there were about twenty-four translations of the Kural in English alone, by both native and non-native scholars, including those by V. V. S. Aiyar, K. M. Balasubramanian, Shuddhananda Bharati, A. Chakravarthy, M. S. Purnalinga Pillai, C. Rajagopalachari, P. S. Sundaram, T. S. Ramalingam Pillai, and Gopalkrishna Gandhi.[17]

Memorials

To honor the author of Tirukkural, a 133-feet (40.6 m) Thiruvalluvar's statue was built in stone. It is located atop a small island near the town of Kanyakumari on the southernmost Coromandel Coast of the Indian peninsula, where two seas and an ocean, viz., the Bay of Bengal, the Arabian Sea, and the Indian Ocean meet.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Blackburn, Cutler (2000). "Corruption and Redemption: The Legend of Valluvar and Tamil Literary History" (PDF). Modern Aian Studies. 34 (2): 449–482. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00003632. Retrieved 20 August 2007.

- ↑ Pillai, MS (1994). Tamil literature. Asian Education Service. ISBN 81-206-0955-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Lal, Mohan (1992). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature. V. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. pp. 4333–4334. ISBN 81-260-1221-8.

- 1 2 Pyatigorsky, Alexander. quoted in K. Muragesa Mudaliar's "Polity in Tirukkural". Thirumathi Sornammal Endowment Lectures on Tirukkural. p. 515.

- ↑ Cutler, Norman (1992). "Interpreting Thirukkural: the role of commentary in the creation of a text". The Journal of the American Oriental Society. 122. Retrieved 20 August 2007.

- 1 2 "Thirukkural translations in different languages of the world". Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ↑ Krishnaswami Aiyangar, S. (1995). Some Contributions of South India to Indian Culture. Asian Educational Services. p. 125. ISBN 81-206-0999-9.

- 1 2 3 Kamil Zvelebil (1973). The smile of Murugan on Tamil literature of South India. BRILL. pp. 156–. ISBN 978-90-04-03591-1. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ↑ "Tirukkural". Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- 1 2 3 Natarajan, P. R. (December 2008). Thirukkural: Aratthuppaal (in Tamil) (First ed.). Chennai: Uma Padhippagam. pp. 1–6.

- 1 2 Thirukkural: Couplets with English Transliteration and Meaning (1 ed.). Chennai: Shree Shenbaga Pathippagam. 2012. pp. vii–xvi.

- 1 2 3 Ravindra Kumar (1 January 1999). Morality and Ethics in Public Life. Mittal Publications. pp. 92–. ISBN 978-81-7099-715-3. Retrieved 13 December 2010.

- ↑ Sujit Mukherjee (1 January 1999). A dictionary of Indian literature. Orient Blackswan. pp. 393–. ISBN 978-81-250-1453-9. Retrieved 13 December 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Rajaram, M. (2009). Thirukkural: Pearls of Inspiration. New Delhi: Rupa Publications. pp. xviii–xxi.

- ↑ Rajaram, M. (2015). Glory of Thirukkural. 915 (1 ed.). Chennai: International Institute of Tamil Studies. pp. 1–104. ISBN 978-93-85165-95-5.

- 1 2 Pope, G. U. The Sacred Kurral of Tiruvalluva Nayanar. pp. xxxi.

- 1 2 3 4 Ramasamy, V. (2001). On Translating Tirukkural (First ed.). Chennai: International Institute of Tamil Studies.

- ↑ A stone inscription found on the walls of a well at the Periya palayathamman temple at Royapettai indicates Ellis' regard for Thiruvalluvar. It is one of the 27 wells dug on the orders of Ellis in 1818, when Madras suffered a severe drinking water shortage. In the long inscription Ellis praises Thiruvalluvar and uses a couplet from Thirukkural to explain his actions during the drought. When he was in charge of the Madras treasury and mint, he also issued a gold coin bearing Thiruvalluvar's image. The Tamil inscription on his grave makes note of his commentary of Thirukkural.Mahadevan, Iravatham. "The Golden coin depicting Thiruvalluvar -2". Varalaaru.com (in Tamil). Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ↑ The original inscription in Tamil written in the Asiriyapa meter and first person perspective: (The Kural he quotes is in Italics)

சயங்கொண்ட தொண்டிய சாணுறு நாடெனும் | ஆழியில் இழைத்த வழகுறு மாமணி | குணகடன் முதலாக குட கடலளவு | நெடுநிலம் தாழ நிமிர்ந்திடு சென்னப் | பட்டணத்து எல்லீசன் என்பவன் யானே | பண்டாரகாரிய பாரம் சுமக்கையில் | புலவர்கள் பெருமான் மயிலையம் பதியான் | தெய்வப் புலமைத் திருவள்ளுவனார் | திருக்குறள் தன்னில் திருவுளம் பற்றிய் | இருபுனலும் வாய்த்த மலையும் வருபுனலும் | வல்லரணும் நாட்டிற் குறுப்பு | என்பதின் பொருளை என்னுள் ஆய்ந்து | ஸ்வஸ்திஸ்ரீ சாலிவாகன சகாப்த வரு | ..றாச் செல்லா நின்ற | இங்கிலிசு வரு 1818ம் ஆண்டில் | பிரபவாதி வருக்கு மேற் செல்லா நின்ற | பஹுதான்ய வரு த்தில் வார திதி | நக்ஷத்திர யோக கரணம் பார்த்து | சுப திநத்தி லிதனோ டிருபத்தேழு | துரவு கண்டு புண்ணியாஹவாசநம் | பண்ணுவித்தேன். - ↑ Blackburn, Stuart (2006). Print, folklore, and nationalism in colonial South India. Orient Blackswan. pp. 92–95. ISBN 978-81-7824-149-4.

- ↑ Zvelebil, Kamil (1992). Companion studies to the history of Tamil literature. Brill. p. 3. ISBN 978-90-04-09365-2.

- ↑ Pope, GU (1886). Thirukkural English Translation and Commentary (PDF). W.H. Allen, & Co. p. 160.

- ↑ http://www.oocities.org/nvkashraf/kur-trans/languages.htm

Further reading

- Blackburn, Stuart. (2000, May). Corruption and Redemption: The Legend of Valluvar and Tamil Literary History. Modern Asian Studies, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 449–482.

- Diaz, S. M. (2000). Tirukkural with English Translation and Explanation. (Mahalingam, N., General Editor; 2 volumes), Coimbatore, India: Ramanandha Adigalar Foundation.

- Drew, W. H. Translated by John Lazarus, Thirukkural (Original in Tamil with English Translation), ISBN 81-206-0400-8

- Klimkeit, Hans-Joachim. (1971). Anti-religious Movement in Modern South India (in German). Bonn, Germany: Ludwig Roehrscheid Publication, pp. 128-133.

- Nehring, Andreas. (2003). Orientalism and Mission (in German). Wiesbaden, Germany: Harrasowitz Publication.

- Subramaniyam, Ka Naa. (1987). Tiruvalluvar and his Tirukkural. New Delhi: Bharatiya Jnanpith.

- Sundaram, P. S. (1990). The Kural. London: Penguin Books.

- Thirukkural with English Couplets L'Auberson, Switzerland: Editions ASSA, ISBN 978-2-940393-17-6.

- Thirunavukkarasu, K. D. (1973). Tributes to Tirukkural: A compilation. In: First All India Tirukkural Seminar Papers. Madras: University of Madras Press. Pp 124.

- Yogi Shuddhananda Bharati (Trans.). (1995, May 15). Thirukkural with English Couplets. Chennai: Tamil Chandror Peravai.

- Zvelevil, K. (1962). Foreword. In: Tirukkural by Tiruvalluvar (Translated by K. M. Balasubramaniam). Madras: Manali Lakshmana Mudaliar Specific Endowments. 327 pages.

External links

- Tirukkural in Tamil and English—Valaitamil.com

- G. U. Pope's English Translation of the Tirukkural

- "Thirukuralisai"—an app promoting Tirukkural through music

- @thirukkuralapps - An interactive twitter search app for Thirukkural in English and Tamil.