Time Gal

| Time Gal | |

|---|---|

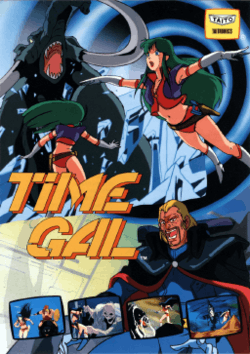

Japanese arcade flyer of Time Gal featuring the protagonist, Reika, and antagonist, Luda. | |

| Developer(s) | Taito |

| Publisher(s) | Taito |

| Designer(s) |

Hidehiro Fujiwara Hiroaki Sato Toshiyuki Nishimura |

| Programmer(s) | Takashi Kuriyama |

| Artist(s) |

Tetsuo Imazawa Hiroshi Wagatsuma |

| Composer(s) | Yoshio Imamura |

| Platform(s) | Arcade, Mega-CD/Sega CD, Sega Saturn, PlayStation, LaserActive |

| Release date(s) |

Arcade

Mega-CD/Sega CD LaserActive

|

| Genre(s) | Interactive movie |

| Mode(s) | Up to 2 players (alternating turns) |

| Cabinet | Upright |

| Display | Horizontal orientation, raster, standard resolution |

Time Gal (Japanese: タイムギャル Hepburn: Taimu Gyaru) is an interactive movie video game developed and published by Taito, and originally released in Japan for the arcades in 1985. It is an action game which uses full motion video (FMV) to display the on-screen action. The player must correctly choose the on-screen character's actions to progress the story. The pre-recorded animation for the game was produced by Toei Animation.

The game is set in a fictional future where time travel is possible. The protagonist, Reika, travels to different time periods in search of a criminal, Luda, from her time. After successfully tracking down Luda, Reika prevents his plans to alter the past.

Time Gal was inspired by the success of earlier laserdisc video games, most notably the 1983 title Dragon's Lair, which also used pre-recorded animation. The game was later ported to the Sega/Mega-CD for a worldwide release, and also to the LaserActive in Japan. The home console versions received a mixed reception.

Gameplay

Time Gal is a FMV-based game which uses pre-recorded animation rather than sprites to display the on-screen action. Gameplay is divided into levels, referred to as time periods. The game begins in 4001 AD with the theft of a time travel device. The thief, Luda, steals the device to take over the world by changing history. Reika, the protagonist also known as Time Gal, uses her own time travel device to pursue him; she travels to different time periods, such as 70,000,000 BC, 44 BC, 1588 AD, and 2010 AD, in search of Luda. Each time period is a scenario which presents a series of threats that must be avoided or confronted. Successfully navigating the sequences allows the player to progress to another period.[1][2][3]

The player uses a joystick and button to input commands, though home versions use a game controller with a directional pad. As the game progresses, visual cues—highlighted portions of the background or foreground—will appear on the screen to help survive the dangers that occur throughout the stage; more difficult settings omit the visual cues. Depending on the location of the cue, the player will input one of four directions (up, down, left and right) or an attack (shoot the target with a laser gun). Inputting the correct command will either avoid or neutralize the threats and progress the game, while incorrect choices result in the character's death. Reika dying too many times results in a game over.[3][4] Specific moments in the game involve Reika stopping time. During these moments, players are presented with a list of three options and have seven seconds to choose the one which will save the character.[5]

Development

The game uses LaserDisc technology to stream pre-recorded animation, which was produced by Japanese studio Toei Animation.[2][4] The game features raster graphics on a CRT monitor and amplified monaural sound.[2] The protagonist's appearance was derived from the main character, Lum, from the Japanese manga and anime series Urusei Yatsura. Several factors prevented an overseas release: a decline in the popularity of laserdisc arcade games in the mid-80s, the expensive price of laserdisc technology, and difficulty to translate.[4] Reika's Japanese dub was voiced by Yuriko Yamamoto.[6]

Release

Since its original release to the arcades in Japan in 1985, Time Gal has been ported to different home formats. It was first released exclusively in Japan by Nippon Victor on the Video High Density format; it could be played on Microsoft's MSX via a Sony laserdisc player.[7][8] The release of Sega's Mega-CD console in 1991 spawned numerous games that took advantage of the CD technology to introduce interactive FMVs. Among the new titles, Time Gal was one of several older laserdisc-based games that were ported to the system.[9][10] Renovation Products acquired the rights to publish Time Gal on the Mega-CD, with Wolf Team handling development.[1] They released it, along with similar games, as part of their "Action-Reaction" series.[11] It was first released in Japan in November 1992, and in North America and Europe the next year.[12]

American press coverage of the Japanese release prompted video game enthusiasts to contact Renovations about a Western release. The number of requests persuaded Renovation's president, Hide Irie, to announce a release in the USA.[13] In addition to being dubbed in English, a few death scenes in the US version were censored.[4] The Mega-CD version uses a smaller color palette than the original, includes a video gallery which requires passwords to view each level's animation sequences, and features a new opening and ending theme by Shinji Tamura and Motoi Sakuraba respectively.[14][15][16] Time Gal was ported to the PlayStation in 1996 as a compilation with Ninja Hayate, another laserdisc arcade game developed by Taito.[4][17] This release lacks the Mega-CD version's additional content, but features a more accurate reproduction of the animation.[4] The compilation was also released on the Sega Saturn the following year.[18] The game can also be played on the Pioneer LaserActive via the Sega Mega-LD module.[19][20] The LaserActive version is the rarest home release of Time Gal, as well as one of the most expensive on the system among collectors.[21]

Reception and legacy

| Reception (Sega CD) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

GamePro magazine noted that "Japanese players ate it up" when it first released in Japanese arcades.[5] However, GameSetWatch's Todd Ciolek believed it was released too late in the life of LaserDisc games, and that players "were getting tired" of the genre's gameplay. He further commented that, despite its gameplay, it was unique and charming.[4] GamePro's reviewer referred to the arcade game as a "lost, laserdisc treasure", and was enthusiastic about its Mega-CD release. He called the death sequences "hilarious" and felt they reduced the tediousness of dying.[5] MEGA magazine rated the Mega-CD version the number five CD game, commenting that though it lacked difficulty, it was a good showcase of the system.[27] Prior to its Mega-CD release, Electronic Gaming Monthly praised the use of CD technology and felt it would be followed by titles with similar gameplay.[28]

Critics praised Time Gal's visuals. GameFan magazine, in praising Wolfteam's port of the game, complimented the Mega-CD version's graphics and short load times.[1] GamePro said the animation is "great, with bright, vivid colors, and fast-paced, exciting movement" and praised the "funny gameplay" and "nonstop action".[24] Shawn Sackenheim of AllGame complimented the animation, calling it "high quality", but criticized the Mega-CD graphics, calling them "downgraded". He commented that, though Time Gal offered a good thrill, it lacked replay value.[14] Author Andy Slaven commented that, though the animation is nice, it can't really be enjoyed while playing.[20] Ciolek echoed similar statements, saying it is more enjoyable to watch than to play. He further commented that the game is frustrating and rigid when compared to more contemporary standards.[4] Electronic Gaming Monthly's group of reviewers praised the Mega-CD version's graphics quality. Three of the four reviewers lauded the gameplay, specifically the challenge and format. The other reviewer stated he didn't care for this type of game, referring to the gameplay as "nothing more than memorizing".[23]

Author Masaru Takeuchi attributes the origin of the quick time event game mechanic to laserdisc games like Dragon's Lair and Time Gal.[29] IGN's Levi Buchanan listed FMV games like Time Gal as one of the reasons behind the Mega-CD's commercial failure, citing them as a waste of the system's capabilities.[30] Ciolek referred to the protagonist as one of the first human heroines in the industry. He further added that Reika was an appealing lead character that Taito could have easily turned into a mascot and featured in other games and media.[4] The character was later included in Alfa System's shooting game Castle of Shikigami III—Taito published the arcade version in Japan.[4][31] In the game, Reika features similar attacks and personality but the character's visual design was updated.[4] Reika's most recent appearance was in the Elevator Action remake Elevator Action Deluxe as one of the few free Taito DLCs.[32]

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Time Gal". GameFan. DieHard Gamers Club. 1 (5): 35. April 1993.

- 1 2 3 "Time Gal Videogame by Taito (1985)". Killer List of Videogames. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- 1 2 Sutyak, Jonathan. "Time Gal - Overview". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Ciolek, Todd (2008-11-13). "Column: 'Might Have Been' - Time Gal". GameSetWatch. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- 1 2 3 Captain Pachinko (April 1993). "Overseas Prospects: Time Gal". GamePro. No. 45. Bob Huseby. p. 138.

- ↑ Japanese Mega CD Manuals. Japanese Mega CD Manuals (in Japanese). Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ "Time Gal for MSX - Technical Information". GameSpot. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ Wolf, Mark J. P. (2008). The Video Game Explosion: A History from Pong to Playstation and Beyond. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-313-33868-7.

- ↑ Fahs, Travis (2009-04-21). "IGN Presents the History of SEGA". IGN. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ Fahs, Travis (2008-03-03). "The Lives and Deaths of the Interactive Movie (Page 3)". IGN. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ "Time Gal Overview". Sega Visions. No. 12. Infotainment World. April–May 1993. p. 53.

- ↑ "Time Gal for Sega CD". GameSpot. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ "Interface: Letters to the Editor". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 45. Ziff Davis. April 1993. p. 14.

- 1 2 3 Sackenheim, Shawn. "Time Gal - Review". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 16, 2014. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ "Mega Play: Time Gal". MEGA. No. 8. Future Publishing. May 1993. p. 64.

- ↑ "Motoi Sakuraba Game Discography". Motoi Sakuraba ~ Official English Website. Motoi Sakuraba. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ "Time Gal & Ninja Hayate for PS". GameSpot. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ "Time Gal & Ninja Hayate Release Information for Saturn". GameFAQs. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ "Time Gal". IGN. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- 1 2 Slaven, Andy (2006). Video Game Bible, 1985 - 2002. Trafford Publishing. p. 291. ISBN 978-1-4122-4902-7.

- ↑ Kohler, Chris (2010-10-14). "The 12 Most Expensive Videogames in Tokyo". Wired News. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- ↑ "Time Gal for Sega CD". GameRankings. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- 1 2 "Review Crew: Time Gal". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 45. Ziff Davis. April 1993. p. 30.

- 1 2 The Tummynator (July 1993). "Sega CD ProReview: Time Gal". GamePro. No. 48. p. 64.

- ↑ Mega, issue 5, pages 42-43.

- ↑ Sega Pro, issue 16, pages 62-63.

- 1 2 "Top Ten CD Games". MEGA. No. 8. Future Publishing. May 1993. p. 89.

- ↑ "International Outlook: Time Gal". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 40. Ziff Davis. November 1992. p. 68.

- ↑ Toyotomi, Kazutaka (2008-10-13). フロム・ソフトウェアイベントレポート (in Japanese). Impress Watch. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ Levi Buchanan (2008-10-28). "RetroCity Podcast, Episode 16: The Sega CD and 32X" (mp3). IGN (Podcast). Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ "The Castle of Shikigami III - Arcade". GameSpy. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ "Elevator Action Deluxe Returns With Additional Stages". Siliconera. Retrieved 2012-06-08.

External links