Thomas Francis Meagher

| Thomas Francis Meagher | |

|---|---|

Thomas Francis Meagher photo taken between 1862 and 1865 | |

| Acting Territorial Governor of Montana | |

|

In office September 1865 – October 3, 1866 | |

| Preceded by | Sidney Edgerton |

| Succeeded by | Green Clay Smith |

|

In office December 1866 – July 1, 1867 | |

| Preceded by | Green Clay Smith |

| Succeeded by | Green Clay Smith |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

August 3, 1823 Waterford, County Waterford, Ireland |

| Died |

July 1, 1867 (aged 43) Missouri River, Montana Territory |

| Military service | |

| Nickname(s) | Meagher of the Sword |

| Allegiance |

Young Ireland Irish Confederation United States of America |

| Service/branch | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 (USA) |

| Rank |

|

| Commands | Company K, 69th New York Militia; Irish Brigade |

| Battles/wars | |

Thomas Francis Meagher (/ˈmɑːr/; August 3, 1823 – July 1, 1867) was an Irish nationalist and leader of the Young Irelanders in the Rebellion of 1848. After being convicted of sedition, he was first sentenced to death, but received transportation for life to Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania) in Australia. In 1852 he escaped and made his way to the United States, where he settled in New York City. There Meagher studied law, worked as a journalist, and traveled to present lectures on the Irish cause. He married for a second time in New York.

At the beginning of the American Civil War, Meagher joined the U.S. Army and rose to the rank of brigadier general.[1] He was most notable for recruiting and leading the Irish Brigade, and encouraging support among Irish immigrants for the Union. He had one surviving son, born in Ireland from his first wife after Meagher was in the United States, and never knew him.

Following the Civil War, Meagher was appointed acting governor of the Montana Territory. In 1867, Meagher drowned in the swift-running Missouri River after falling from a steamboat at Fort Benton. Timothy Egan, author of a 2016 biography on Meagher, has suggested that the governor was murdered by Montana opponents.[2]

Family

Thomas Francis Meagher was born in what is now The Granville Hotel on the Quay in Waterford City, Ireland. From the age of two he lived with his family at nearby Number 19, The Mall.[3] His father, Thomas Meagher (1796–1874), was a wealthy merchant who had retired to enter politics. He was twice elected Mayor of the City, which he also represented in Parliament from August 1847 to March 1857. He had lived in the city since he was a young man, having migrated from Newfoundland in present-day Canada.[4]

The senior Meagher was born in St John's, Newfoundland. His father, also named Thomas (1763–1837),[5] had emigrated as a young man from County Tipperary just before the turn of the 18th century. Starting as a farmer, the grandfather Meagher became a trader, and advanced to merchant, and shipowner. Newfoundland was the only British colony where the Irish constituted a majority of the population.[6] The senior Thomas Meagher married the widow Mary Crotty.[5] He established a prosperous trade between St. John's and Waterford, Ireland. Later, the grandfather placed his eldest son Thomas in Waterford to represent their business interests. With the son Thomas' move to Waterford, the Meagher family had come full circle, returning to Ireland to prosper. The son Thomas became a successful merchant in Waterford, whose economic success was followed by political office.[6]

Thomas Francis Meagher's mother, Alicia Quan (1798–1827), was the second eldest daughter of Thomas Quan and Alicia Forristall. Her father was a partner in the trading and shipping firm known as Wye, Cashen and Quan of Waterford. She died when Meagher was three and a half years old, after the birth of twin girls. (One of the girls also died then; the other at age seven.) Meagher had four siblings; a brother Henry and three sisters. Only his older sister Christine Mary lived past childhood.[7]

Early life and education

Meagher was educated at Catholic boarding schools. When Meagher was eleven, his family sent him to the Jesuits at Clongowes Wood College in County Kildare.[8] It was at Clongowes that he developed his skill of oratory, becoming at age 15 the youngest medalist of the Debating Society.[9] These oratory skills would later distinguish Meagher during his years as a leading figure in Irish Nationalism.[10] Though he gained a broad and deep education at Clongowes,[9] as was typical, it did not include much about the history of his country or matters relating to Ireland.[8]

After six years, Meagher left Ireland for the first time,[11] to study in England at Stonyhurst College, a Jesuit institution in Lancashire.[10] By the late 19th century, it was the largest Catholic college in England.[12] Meagher's father regarded Trinity College, the only university in Ireland, as being both anti-Irish and anti-Catholic.[8]

The younger Meagher established a reputation for developed scholarship and "rare talents."[10] While Meagher was at Stonyhurst, his English professors struggled to overcome his "horrible Irish brogue"; he acquired an Anglo-Irish upper-class accent that in turn grated on the ears of some of his countrymen.[13] Despite his English accent and what some people perceived as a "somewhat affected manner," Meagher had so much eloquence as an orator as to lead his countrymen to forget his English idiosyncrasies. Meagher became a popular speaker "who had no compare" in Conciliation Hall, the meeting place of the Irish Repeal Association.[14][15][16]

The white in the centre signifies a lasting truce between the 'Orange' and the 'Green', and I trust that beneath its folds the hands of the Irish Protestant and the Irish Catholic may be clasped in generous and heroic brotherhood.

Thomas Francis Meagher: On presenting the flag to the people of Dublin April 1848

Young Ireland

Meagher returned to Ireland in 1843,[17] with undecided plans for a career in the Austrian army, a tradition among a number of Irish families.[13] In 1844 he traveled to Dublin with the intention of studying for the bar. He became involved in the Repeal Association, which worked for repeal of the Act of Union between Great Britain and Ireland.[18] Meagher was influenced by writers of The Nation newspaper and fellow workers in the Repeal movement.[13] The movement was nationwide. At a Repeal meeting held in Waterford on December 13, at which his father presided, Meagher acted as one of the Secretaries.[18] He soon became popular on Burgh Quay,[19] his eloquence at meetings making him a celebrated figure in the capital. Any announcement of Meagher's speaking would ensure a crowded hall.[13]

In June 1846, the administration of Sir Robert Peel’s Tory Ministry fell, and the Liberals under Lord John Russell came to power. Daniel O’Connell tried to lead the Repeal movement to support both the Russell administration and English Liberalism. Repeal agitation was damped down in return for a distribution of generous patronage through Conciliation Hall.[20] On June 15, 1846, Meagher denounced English Liberalism in Ireland, as he suspected the national cause of Repeal would be sacrificed to the Whig government. He thought the people striving for freedom would be "purchased back into factious vassalage."[21] Meagher and the other "Young Irelanders" (the epithet used by O’Connell to describe the young men of The Nation)[20] vehemently denounced any movement toward English political parties, so long as Repeal was denied.

The promise of patronage and influence divided the Repeal Movement. Those who hoped to gain by government positions, also called The "Tail", and described as the "corrupt gang of politicians who fawned on O’Connell" wanted to drive the Young Irelanders from the Repeal Association.[22] Such opponents portrayed the Young Irelanders as revolutionaries, factionists, infidels and secret enemies of the Catholic Church.[21] On July 13, O'Connell's followers introduced resolutions to declare that under no circumstances was a nation justified in asserting its liberties by force of arms.[22]

In fact, the Young Irelanders had not, until then, advocated the use of physical force to advance the cause of repeal and opposed any such policy.[23] The "Peace Resolutions" declared that physical force was immoral under any circumstances to obtain national rights. Although Meagher agreed that only moral and peaceful means should be adopted by the Association, he also said that if Repeal could not be carried by those means, he would adopt the more perilous risky but no less honorable choice of arms. When the Peace resolutions were proposed again on July 28, Meagher responded with his famous "Sword Speech".[24]

Meagher held the Peace Resolutions were unnecessary. He believed that under existing circumstances, any provocation to arms would be senseless and wicked. He dissented from the Resolutions because of not wanting to pledge to the unqualified repudiation of physical force "in all countries, at all times, and in every circumstance." He knew there were times when arms would suffice, and when political amelioration called for "a drop of blood, and many thousand drops of blood." He "eloquently defended physical force as an agency in securing national freedom."[25] As Meagher carried the audience to his side, O'Connell's supporters believed they were at risk in not being able to drive out the Young Irelanders. O’Connell’s son John interrupted Meagher to declare that one of them had to leave the hall. William Smith O’Brien protested against John O’Connell’s attempt to suppress a legitimate expression of opinion, and left the meeting with other prominent Young Irelanders in defiance, never to return.[22][25]

Irish Confederation

In January 1847, Meagher, together with John Mitchel, William Smith O'Brien, and Thomas Devin Reilly formed a new repeal body, the Irish Confederation. In 1848, Meagher and O'Brien went to France to study revolutionary events there, and returned to Ireland with the new Flag of Ireland, a tricolour of green, white and orange made by and given to them by French women sympathetic to the Irish cause.[26] The acquisition of the flag is commemorated at the 1848 Flag Monument in the Irish parliament. The design used in 1848 was similar to the present flag, except that orange was placed next to the staff, and the red hand of Ulster decorated the white field. This flag was first flown in public on March 1, 1848, during the Waterford by-election, when Meagher and his friends flew the flag from the headquarters of Meagher's "Wolfe Tone Confederate Club" at No. 33, The Mall, Waterford.[27]

Following the incident known as the Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848 or "Battle of Ballingarry" in August 1848, Meagher, Terence MacManus, O'Brien, and Patrick O'Donoghue were arrested, tried and convicted for sedition. Due to a newly passed ex post facto law, the sentence meant that Meagher and his colleagues were sentenced to be "hanged, drawn and quartered". It was after his trial that Meagher delivered his famous Speech From the Dock.[28]

While awaiting execution in Richmond Gaol, Meagher and his colleagues were joined by Kevin Izod O'Doherty and John Martin. But, due to public outcry[29] and international pressure,[30] royal clemency commuted the death sentences to transportation for life to "the other side of the world." In 1849 all were sent to Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania, Australia).[31][32] On July 20, the day after being notified of his exile to Van Diemen's Land, Meagher announced that he wished henceforth to be known as Thomas Francis O'Meagher.[33]

Van Diemen's Land

My Lord, this is our first offense, but not our last. If you will be easy with us this once, we promise on our word as gentleman to try better next time.

Thomas Francis Meagher: Promising the judge before passing sentence

Meagher accepted the "ticket-of-leave" in Tasmania, giving his word not to attempt to escape without first notifying the authorities, in return for comparative liberty on the island. A further stipulation was that each of the Irish "gentleman" convicts were sent to reside in separate districts: Meagher to Campbell Town and shortly after to Ross (where his cottages still stand); MacManus to Launceston and later near New Norfolk; Kevin O'Doherty to Oatlands; John Mitchel and John Martin to Bothwell; and O'Brien (who initially refused a ticket-of-leave) to the "Penal Station" on Maria Island and later to New Norfolk. During his time in Tasmania, Meagher managed to meet clandestinely with his fellow Irish rebels, especially at Interlaken on Lake Sorell.[34][35]

Marriage and family

On February 22, 1851 in Tasmania, Meagher married Katherine Bennett ("Bennie"). She was the daughter of Bryan Bennett, a convicted highwayman.[36] His fellow exiles disapproved of his marriage. Soon after they were married, Katherine became ill.[37] Less than a year after his wedding in January 1852, Meagher abruptly surrendered his "ticket-of-leave" and planned his escape to the United States. Meagher sent his "ticket-of-leave" and a letter to the authorities, along with notifying them he would consider himself a free man in twenty-four hours. When he escaped, Katherine was in an advanced stage of pregnancy and stayed behind. Following Meagher's departure from Van Diemen's Land, their son was born, but he died at 4 months of age, shortly after Meagher reached New York City.

The infant son was buried at St. John's Catholic Church, the oldest Catholic church in Australia, in Richmond, Tasmania, Australia. The small grave is next to the church. A plaque notes his father Meagher's being an Irish Patriot and member of the Young Irelanders.[38]

Following Meagher's escape, Katherine was taken to Ireland. Eventually she was able to spend a short time in the United States with Meagher.[38] She returned to Ireland pregnant and in poor health. She gave birth to Meagher's only child: a boy, Thomas Francis Meagher, named after his father. She died in Ireland in May 1854, at the home of Meagher's father.[36] Meagher never met his son, who was raised by the senior Meaghers and relatives, and remained in Ireland all his life.[36]

After Meagher settled in New York, he soon courted Elizabeth Townsend, the daughter of Peter Townsend and Caroline (née) Parish of Monroe, New York.[36] The Townsend family were wealthy Protestants, who opposed Meagher's marrying their daughter but they eventually relented. Elizabeth converted to Catholicism, and in 1856 she and Meagher married.[39]

Immigration to the United States

Meagher arrived in New York City in May 1852. He studied law and journalism, and became a noted lecturer. Soon after, Meagher became a United States citizen.[40] He eventually founded a weekly newspaper called the Irish News.[32][36] Meagher and John Mitchel, who had also since escaped, published the radical pro-Irish, anti-British Citizen.[41] After his escape, the question of "honor" was raised by Mitchel, among others. Meagher agreed to be "tried" by American notables, and vowed to return to Van Diemen's Land if they held against him. The simulated court martial found for Meagher, and he was vindicated.[38]

Prior to the outbreak of the American Civil War, Meagher traveled to Costa Rica, in part to determine whether Central America would be suitable for Irish immigration.[42] He used his experiences as the basis for writing travel articles which were published in Harper's Magazine.[43] He was commissioned as a captain in the New York State Militia.[44]

American Civil War

It is not only our duty to America, but also to Ireland. We could not hope to succeed in our effort to make Ireland a Republic without the moral and material support of the liberty-loving citizens of these United States.— Thomas Francis Meagher On deciding to fight for the Union

Meagher's decision to serve the Union was not a simple one; before the onset on the war, he had supported the South. He had visited the South to lecture, and was sympathetic to its people.[45] Further, his Irish friend John Mitchel, who had settled in the South, supported the secessionists. Meagher and Mitchel split over the issue of slavery.[46] Mitchel went to the Confederate capitol in Richmond, Virginia, and his three sons served with the Confederate States Army.

On April 12, 1861, the first shots were fired at U.S. held Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. This action by the South pushed Meagher into support of the Union cause.[45] In lectures, including a famous speech made at the Boston Music Hall in September 1861, he implored the Irish of the North to defend the Union.[47][48] He began recruiting, advertising in local newspapers to form Company K of the 69th Regiment. It became known as the "Fighting 69th" of the New York State Militia. One of his ads in the New-York Daily Tribune read: "One hundred young Irishman—healthy, intelligent and active—wanted at once to form a Company under command of Thomas Francis Meagher."[45]

With the beginning of war, Meagher volunteered to fight for the Union. He recruited a full company of infantrymen to be attached to the U.S. 69th Infantry Regiment New York State Volunteers on April 29, 1861[44] the regiment was added to Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell's Army of Northeastern Virginia. Colonel Corcoran initially commanded them, but was captured during the battle. Despite the Confederate victory, the Irish of New York's 69th fought bravely, winning praise from the media and support from the Irish of New York.[49]

Following the First Battle of Bull Run, Meagher returned to New York to form the Irish Brigade.[50] He was commissioned brigadier general (effective February 3) to lead them[44] in the Peninsula Campaign of 1862.

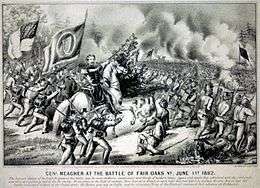

In late May during the Battle of Fair Oaks, part of the Peninsula Campaign, Meagher saw his first battle as a brigadier general. The Union won a defensive victory at Fair Oaks and the Irish Brigade furthered their reputation as fierce fighters.

This reputation was solidified when the New York printmaker Currier and Ives published a lithograph depicting Meagher on horseback leading his brigade at bayonet charge.[51] Following the Battle of Fair Oaks, Meagher was given command of a non-Irish regiment. This experiment was unsuccessful, and thereafter Meagher would only command Irishmen.[52] Meagher's troops engaged during the Peninsula Campaign at the Battle of Gaines' Mill on June 27. The Irish Brigade arrived in battle after a quick march though the Chickahominy River, as reinforcements for Fitz John Porter's weakening forces. Later, this march and battle were considered by historians as the highlight of Meagher's military career.[53]

The Irish Brigade suffered huge losses at the Battle of Antietam that fall. Meagher's brigade led an attack at Antietam on September 17 against the Sunken Road (later referred to as "Bloody Lane") and lost 540 men to heavy volleys before being ordered to withdraw.[54][55] During the battle, Meagher was injured when he fell off his horse. Some reports said Meagher had been drunk.[56] But, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's official report noted that Meagher's horse had been shot.[57] Meagher had faced false reports of drunkenness at the First Battle of Bull Run.[58] The high number of casualties at Antietam, and the rumors of being drunk on the battlefield, increased criticism of Meagher's command ability.[56]

The Irish Brigade suffered its largest losses at the Battle of Fredericksburg. Brigade chaplain Father William Corby later said, it was "a body of about 4,000 Catholic men marching – most of them – to death."[59] Meagher led 1,200 men into battle, and "two hundred and eighty men only appeared under arms to represent the Irish Brigade" the next morning.[60] Meagher took no direct part in this battle, remaining at the rear when his brigade began their advance, due to, what he described in his official report as 'a most painful ulcer in the knee joint'.[61]

Meagher spent the next four months recovering from his injuries and took charge of his command three days prior to the Battle of Chancellorsville.[62] After limited engagement at Chancellorsville, Meagher resigned his commission on May 14, 1863.[44] The Army had refused his request to return to New York to raise reinforcements for his battered brigade.[63] The brigade was 4,000 strong in mid–May 1862, but by late May 1863 it had only a few hundred combat-ready men left.[64]

Following the death of Brig. Gen. Michael Corcoran, another leading Irish political figure, the Army rescinded Meagher's resignation on December 23.[44] He was assigned to duty in the Western Theater beginning in September 1864. He commanded the District of Etowah in the Department of the Cumberland from November 29 to January 5, 1865. Meagher briefly commanded a provisional division within the Army of the Ohio from February 9–25, and resigned from the U.S. Army on May 15.[44]

Territorial governorship of Montana

After the war, Meagher was appointed Secretary of the new Territory of Montana; soon after arriving there, he was designated Acting Governor.[65] Meagher attempted to create a working relationship between the territory's Republican executive and judicial branches, and the Democratic legislative branch. He failed, making enemies in both camps. Further, he angered many when he pardoned a fellow Irishman who had been convicted of manslaughter.[65]

The Territory of Montana was created from the eastern portion of Idaho Territory as its population increased with an influx of settlers following the discovery of gold in 1862. When the Civil War ended, many more settlers entered the territory. Searching for riches, they often disregarded U.S. treaties with the local Native American tribes. In 1867, Montana pioneer John Bozeman was allegedly killed by a band of Blackfeet, who attacked other settlers as well. Meagher responded by organizing the Montana Territory Volunteer Militia to retaliate. He secured funding from the federal government to campaign against the Native Americans, but was unable to find the offenders, or retain the militia's cohesion. He was later criticized for his actions.[66]

Meagher called Montana's first constitutional convention to develop a constitution as a step toward statehood. Not enough residents voted for the constitution and statehood to qualify. In addition, copies of the constitution were lost on the way to a printer, and Congress never received copies for review. Montana gained statehood in 1889, more than 20 years after Meagher's death.[67]

Disappearance

In the summer of 1867, Meagher traveled to Fort Benton, Montana, to receive a shipment of guns and ammunition sent by General Sherman for use by the Montana Militia.[68] On the way to Fort Benton, the Missouri River terminus for steamboat travel, Meagher fell ill and stopped for six days to recuperate. When he reached Fort Benton, he was reportedly still ill.[69] Sometime in the early evening of July 1, 1867, Meagher fell overboard from the steamboat G. A. Thompson, into the Missouri. The pilot described the waters as "...instant death – water twelve feet deep and rushing at the rate of ten miles an hour."[70] His body was never recovered.[44]

Because Meagher was outspoken and controversial and his body was not recovered, some believed his death to be suspicious and many theories circulated about his death.[32] Early theories included that he was murdered by a Confederate soldier from the war,[71] or by Native Americans.[72] In 1913 a man claimed to have carried out the murder of Meagher for the price of $8000, but then recanted.[73][74]

By the late 20th century, John T. Hubbell suggested that Meagher had been drinking, and fell overboard.[75] American journalist and writer Timothy Egan, who published a biography of Meagher in 2016, suggested that he may have been murdered by Montana political enemies or powerful and still active vigilantes. On the frontier men were quick to kill rather than adjudicate.[2]

Meagher was survived by his American second wife, Elizabeth Townsend (1840–1906). He was also survived by his second son by his first wife Katherine Bennett. Their first son died as an infant in Tasmania. Katherine gave birth to the second son in Ireland after being with Meagher for a time in the United States. She died soon after the birth, and their son grew up in Ireland reared by his father's family. They never met each other.[36]

Legacy and honors

- The Thomas F. Meagher Foundation promotes pride in and respect for the Irish flag, and is leading centennial celebrations of the adoption of the Irish tricolor in Ireland.[76][77]

- A statue of Meagher, on horseback with sword raised, is on the front lawn of the Montana State Capitol in Helena,[78] and was first erected in 1905.[79]

- A similar statue honoring him was erected in 2004 in Waterford, Ireland near his home at 19 The Mall.[71][80]

- In 1982, the Ancient Order of Hibernians formed the Thomas Francis Meagher Division #1 in Helena, Montana, dedicated to the principles of the Order and to restoring a historically accurate record of Meagher's contributions to Montana.[81]

- The military fort at Camden near Crosshaven, County Cork was renamed Fort Meagher.

- Meagher County, Montana was named for him.[82]

- A monument at the Antietam battlefield was dedicated in his honor.[83] The inscription on the granite monument reads:

The Irish Brigade commander was born in Waterford City, Ireland on August 23, 1823; a well educated orator, he joined the young Ireland movement to liberate his nation. This led to his exile to a British Penal Colony in Tasmania Australia in 1849. He escaped to the United States in 1852 and became an American citizen. When the Civil War broke out, he raised Company K, Irish Zouaves, for the 69th New York State Militia Regiment, which fought at First Bull Run under Colonel Michael Corcoran. Subsequently Meagher raised the Irish Brigade and commanded it from February 3, 1862 to May 14, 1863 til later commanded a military district in Tennessee. After the War Meagher became Secretary and Acting Governor of the Montana Territory. He drowned in the Missouri River near Fort Benton on July 1, 1867. His body was never recovered.

- A cenotaph memorial to Meagher is in Greenwood Cemetery, New York City[84]

- In the spring of 1867, the U.S. Army established a post near Rocky Creek, east of Bozeman, Montana and named it Fort Elizabeth Meagher in honor of Meagher's second wife.[85]

- At the New York-New York Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas, a statue depicting Meagher in uniform was dedicated near the Brooklyn bridge directly facing the Las Vegas strip.

- On December 3, 1944 the Liberty Ship S.S. Thomas F. Meagher was launched

- In March 2015 the Suir Bridge, crossing the river Suir outside Waterford, Ireland, was renamed the Thomas Francis Meagher Bridge by the President of Ireland Michael D Higgins.[86]

- In December 1987, the General Thomas F. Meagher Division 1 of the City of Fredericksburg (Virginia)[87] of the Ancient Order of Hibernians was formed

See also

References

- Specific

- ↑ Meagher had at various times been appointed a brevet major general

- 1 2 Mary Ann Gwinn, "From Dublin to Montana/ Timothy Egan on his new book 'The Immortal Irishman' ", The Seattle Times, 25 Feb. 2016. Quote: "There were no trials, they just pulled out people they didn’t like. Meagher pardoned a man, and then they grabbed him and hanged him the same day, with Meagher’s message in his pocket. I think there is pretty good evidence, without being 100 percent sure, that he was murdered."

- ↑ "Thomas Francis Meagher" (PDF). Waterford Themes and People. Waterford County Library. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ↑ O'Sullivan pg.192

- 1 2 Cavanagh 1892, p 12

- 1 2 Duffy, FYIH, pg.10

- ↑ Wylie 2007, p 20

- 1 2 3 Griffith pg.IV (preface)

- 1 2 Cavanagh 1892, p 19

- 1 2 3 Lyons pg10

- ↑ Lonergan 1913, p 112

- ↑ "Stonyhurst College", Catholic Encyclopaedia (1912), retrieved 18 July 2008

- 1 2 3 4 Griffith pg.V (preface)

- ↑ O’Sullivan pg. 193

- ↑ Ua Cellaigh pg 152-3

- ↑ Lyons pg 11

- ↑ 1843 the "Repeal year" according to Daniel O’Connell

- 1 2 O'Sullivan pg 193

- ↑ O'Sullivan pg. 193

- 1 2 Griffith pg.VI (preface)

- 1 2 O'Sullivan pg 195

- 1 2 3 Griffith pg.VII (preface)

- ↑ Doheny Pg 105

- ↑ O'Sullivan pg 195-6

- 1 2 O'Sullivan pg 196

- ↑ "The National Flag: Design" (PDF). Department of the Taoiseach. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- ↑ Cavanagh 1892, p 100

- ↑ Lyons 2007, pp 15-20

- ↑ Wylie 2007, p 61

- ↑ Cavanagh 1892, p 294

- ↑ Lyons 2007, p 20

- 1 2 3 Burgess, Hank (2002-01-09). "Remembering Meagher" (PDF). Independent Record. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- ↑ Athearn, Robert G. (1949). Thomas Francis Meagher: An Irish Revolutionary in America. University of Colorado Press. p. 16. ISBN 0-8061-3847-5.

- ↑ Mitchel, John (1854). Jail journal, or, Five years in British prisons. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- ↑ Akenson 2006, p 122

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lonergan 1913, p 115

- ↑ Wylie 2007, pp 74-77

- 1 2 3 Akenson 2006, p 125-127

- ↑ Wylie 2007, pp 96-97

- ↑ Cavanagh 1892, p 367

- ↑ Dillon, William (1888). Life of John Mitchel. K. Paul, Trench. p. 39. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- ↑ Wylie 2007, pp 105

- ↑ Meagher, Thomas Francis (2004). "Holidays in Costa Rica". In Palmer, Steven Paul; et al. The Costa Rica Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press. pp. 69–83. ISBN 978-0-8223-3372-2. Retrieved 2008-06-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Eicher, p. 385.

- 1 2 3 Wylie 2007, pp 117-121

- ↑ Akenson 2006, p 345-346

- ↑ Lonergan 1913, pp 115-116

- ↑ Lyons 2007, pp 91-119

- ↑ Bruce 2006, pp 78-79

- ↑ Lyons 2007, pp 82-88

- ↑ Wylie 2007, pp 148-150

- ↑ Wylie 2007, pp 151-152

- ↑ Wylie 2007, pp 154-155

- ↑ Bailey, Ronald H., and the Editors of Time-Life Books, The Bloodiest Day: The Battle of Antietam, p. 100, Time-Life Books, 1984, ISBN 0-8094-4740-1.

- ↑ Meagher, Thomas Francis (September 30, 1862). "Meagher's Report of the Battle of Antietam". CivilWarHome.com. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- 1 2 Bruce 2006, p 120

- ↑ Wylie 2007, p 165

- ↑ Bruce 2006, p 89

- ↑ Wylie 2007, p 145

- ↑ Meagher, Thomas Francis (December 20, 1862). "Meagher's Report of the Battle of Fredericksburg". CivilWarHome.com. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- ↑ Official Records, Vol21, p243

- ↑ Wylie 2007, pp 184-185

- ↑ Cavanagh 1892, p 485

- ↑ Wylie 2007, p 181

- 1 2 Allen, Fredrick (Spring 2001). "Montana Vigilantes: and the Origins of the 3-7-77". MT.Gov. Montana The Magazine of Western History. pp. 3–19. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- ↑ Rzeczkowski, Frank. "The Crow Indians and the Bozeman Trail". MT.Gov. Montana Historical Society. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- ↑ "The Blessings of Liberty: Montana's Constitutions". MT.Gov. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- ↑ Lonergan 1913, pp. 124-125

- ↑ Wylie 2007, pp 306-307

- ↑ Lonergan 1913, pp 125

- 1 2 O'Connor, John (June 13, 2008). "Thomas Francis Meagher: Tales of the Tellurians". The Munster Express. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ "Obituary of Mrs. Meagher, July 8, 1906" (PDF). New York Times. 1906-07-08. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ Wylie 2007, pp 313

- ↑ "Says He Slew Gen. Meagher, May 30, 1913" (PDF). New York Times. May 30, 1913. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ↑ ed. by John T. Hubbell ...; Hubbell, John T.; Geary,James W. ; Wakelyn Jon L. (1995). Biographical Dictionary of the Union: Northern Leaders of the Civil War. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 347. ISBN 0-313-20920-0. Retrieved 2008-08-05. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ "Fifteen facts about the Irish flag and 1916". The Irish Times. Sep 23, 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ↑ "THOMAS F. MEAGHER FOUNDATION".

- ↑ Bohlinger, John (July 5, 2005). "Speech: Rededication of Thomas Meagher Statue". MT.Gov. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- ↑ Wylie 2007, pp 329

- ↑ Lambert, Tim. "A brief history of Waterford". LocalHistories.org. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ http://www.hibernian.org/helena/index.html

- ↑ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 204.

- ↑ "Irish Brigade Monument". NPS.gov. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ Thomas Francis Meagher at Find a grave

- ↑ Miller, Don C.; Cohen, Stan (1978). Military and Trading Posts of Montana. Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company. p. 58. ISBN 0-933126-01-8.

- ↑ http://www.1848tricolour.com/2015-programme/

- ↑ http://www.aohvirginia.org/FredericksburgDiv1/division-history/

- General

- Akenson, Donald H. (2006). An Irish History of Civilization. McGill-Queen's Press-MQUP. ISBN 0-7735-2891-1.

- Bruce, Susannah Ural (2006). The Harp and the Eagle: Irish-American Volunteers and the Union Army, 1861-1865. NYU Press. ISBN 0-8147-9940-X.

- Cavanagh, Michael (1892). Gen. Thomas Francis Meagher - The Leading Events of his career. Worchester, MA: The Messenger Press.

- Doheny, Michael (1951). The Felon's Track. Dublin: M. H. Gill & Son.

- Duffy, Charles Gavan (1888). Four Years of Irish History 1845-1849. London: Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co.

- Duffy, Charles Gavan (1880). Young Ireland. London: Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co.

- Dungan, Myles (2006). How the Irish Won the West. Dublin: New Ireland. ISBN 978-1-905494-60-6.

- Eicher, John H.; Simon, John Y. (2001). Civil War High Commands. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Griffith, Arthur (1916). Meagher of the Sword, :Speeches of Thomas Francis Meagher in Ireland 1846-1848. Dublin: M. H. Gill & Son, Ltd.

- Jones, Donald R (2009). The Harp & The Eagle. Baltimore, MD: American Literary Press. ISBN 978-1-934696-40-8.

- Keneally, Thomas (1998). The Great Shame: And the Triumph of the Irish in the English-Speaking World. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-1-856197-88-5.

- Lonergan, Thomas S. (1913). Daly, Edward Hamilton, ed. General Thomas Francis Meagher. The Journal of the American-Irish Historical Society. XII. The Society. pp. 111–126.

- Lyons, W. F. (2007). Brigadier-General Thomas Francis Meagher - His Political and Military Career. Dickens Press. ISBN 1-4067-3027-0.

- O'Sullivan, T. F. (1945). Young Ireland. The Kerryman Ltd.

- Ua Cellaigh, Seán; Sullivan, T. D., A. M., and D. B. (1953). Speeches from the Dock. Dublin: M. H. Gill & Son. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - Wylie, Paul R. (2007). The Irish General: Thomas Francis Meagher. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3847-5.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Thomas Francis Meagher |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Thomas Francis Meagher |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thomas Francis Meagher. |

- An Apology for the British Government in Ireland, John Mitchel, O Donoghue & Company 1905, 96 pages

- Jail Journal: Commenced on Board the "Shearwater" Steamer, in Dublin Bay ..., John Mitchel, M.H. Gill & Sons, Ltd 1914, 463 pages

- Jail Journal: with continuation in New York & Paris, John Mitchel, M.H. Gill & Son, Ltd

- The Crusade of the Period, John Mitchel, Lynch, Cole & Meehan 1873

- Last Conquest Of Ireland (Perhaps), John Mitchel, Lynch, Cole & Meehan 1873

- History of Ireland, from the Treaty of Limerick to the Present Time, John Mitchel, Cameron & Ferguson

- History of Ireland, from the Treaty of Limerick to the Present Time (2 Vol), John Mitchel, James Duffy 1869

- Life of Hugh O'Neil John Mitchel, P.M. Haverty 1868

- The Last Conquest of Ireland (Perhaps), John Mitchel, (Glasgow, 1876 - reprinted University College Dublin Press, 2005) ISBN 1-905558-36-4

- The Felon's Track, Michael Doheny, M.H. Gill & Sons, Ltd 1951 (Text at Project Gutenberg)

- The Volunteers of 1782, Thomas Mac Nevin, James Duffy & Sons. Centenary Edition

- Thomas Davis, Sir Charles Gavan Duffy, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co, Ltd 1890

- My Life In Two Hemispheres (2 Vol), Sir Charles Gavan Duffy, T. Fisher Unwin. 1898

- Young Ireland, Sir Charles Gavan Duffy, Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co 1880

- Four Years of Irish History 1845-1849, Sir Charles Gavan Duffy, Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co 1888

- A Popular History of Ireland: from the Earliest Period to the Emancipation of the Catholics, Thomas D'Arcy McGee, Cameron & Ferguson (Text at Project Gutenberg)

- The Patriot Parliament of 1689, Thomas Davis, (Third Edition), T. Fisher Unwin, MDCCCXCIII

- Charles Gavan Duffy: Conversations With Carlyle (1892)

- Davis, Poem’s and Essays Complete, Introduction by John Mitchel, P. M. Haverty, P.J. Kenedy, 9/5 Barclay St. New York, 1876.

- Additional Reading

- The Politics of Irish Literature: from Thomas Davis to W.B. Yeats, Malcolm Brown, Allen & Unwin, 1973.

- John Mitchel, A Cause Too Many, Aidan Hegarty, Camlane Press.

- Thomas Davis, The Thinker and Teacher, Arthur Griffith, M.H. Gill & Son 1922.

- Brigadier-General Thomas Francis Meagher His Political and Military Career,Capt. W. F. Lyons, Burns Oates & Washbourne Limited 1869

- Young Ireland and 1848, Dennis Gwynn, Cork University Press 1949.

- Daniel O'Connell The Irish Liberator, Dennis Gwynn, Hutchinson & Co, Ltd.

- O'Connell Davis and the Collages Bill, Dennis Gwynn, Cork University Press 1948.

- Smith O’Brien And The "Secession", Dennis Gwynn,Cork University Press

- Meagher of The Sword, Edited By Arthur Griffith, M. H. Gill & Son, Ltd. 1916.

- Young Irelander Abroad The Diary of Charles Hart, Edited by Brendan O'Cathaoir, University Press.

- John Mitchel First Felon for Ireland, Edited By Brian O'Higgins, Brian O'Higgins 1947.

- Rossa's Recollections 1838 to 1898, Intro by Sean O'Luing, The Lyons Press 2004.

- Labour in Ireland, James Connolly, Fleet Street 1910.

- The Re-Conquest of Ireland, James Connolly, Fleet Street 1915.

- John Mitchel Noted Irish Lives, Louis J. Walsh, The Talbot Press Ltd 1934.

- Thomas Davis: Essays and Poems, Centenary Memoir, M. H Gill, M.H. Gill & Son, Ltd MCMXLV.

- Life of John Martin, P. A. Sillard, James Duffy & Co., Ltd 1901.

- Life of John Mitchel, P. A. Sillard, James Duffy and Co., Ltd 1908.

- John Mitchel, P. S. O'Hegarty, Maunsel & Company, Ltd 1917.

- The Fenians in Context Irish Politics & Society 1848-82, R. V. Comerford, Wolfhound Press 1998

- William Smith O'Brien and the Young Ireland Rebellion of 1848, Robert Sloan, Four Courts Press 2000

- Irish Mitchel, Seamus MacCall, Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd 1938.

- Ireland Her Own, T. A. Jackson, Lawrence & Wishart Ltd 1976.

- Life and Times of Daniel O'Connell, T. C. Luby, Cameron & Ferguson.

- Young Ireland, T. F. O'Sullivan, The Kerryman Ltd. 1945.

- Irish Rebel John Devoy and America's Fight for Irish Freedom, Terry Golway, St. Martin's Griffin 1998.

- Paddy's Lament Ireland 1846-1847 Prelude to Hatred, Thomas Gallagher, Poolbeg 1994.

- The Great Shame, Thomas Keneally, Anchor Books 1999.

- James Fintan Lalor, Thomas, P. O'Neill, Golden Publications 2003.

- Charles Gavan Duffy: Conversations With Carlyle (1892), with Introduction, Stray Thoughts On Young Ireland, by Brendan Clifford, Athol Books, Belfast, ISBN 0-85034-114-0. (Pg. 32 Titled, Foster’s account Of Young Ireland.)

- Envoi, Taking Leave Of Roy Foster, by Brendan Clifford and Julianne Herlihy, Aubane Historical Society, Cork.

- The Falcon Family, or, Young Ireland, by M. W. Savage, London, 1845. (An Gorta Mor)Quinnipiac University