Third Republic of Madagascar

| Republic of Madagascar | ||||||||||||

| Repoblikan'i Madagasikara République de Madagascar | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Motto Tanindrazana, Fahafahana, Fandrosoana "Fatherland, Freedom, Progress" | ||||||||||||

| Anthem Ry Tanindrazanay malala ô! "Oh, beloved land of our ancestors!" | ||||||||||||

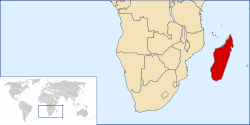

Location of the Republic of Madagascar in Africa | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Antananarivo | |||||||||||

| Languages | Malagasy · French · English[1] | |||||||||||

| Religion | Christianity · Traditional beliefs | |||||||||||

| Government | Republic | |||||||||||

| President | ||||||||||||

| • | 1992–1993; 1997-2002 | Didier Ratsiraka | ||||||||||

| • | 1993-1996 | Albert Zafy | ||||||||||

| • | 1996-1997 | Norbert Ratsirahonana | ||||||||||

| • | 2002-2009 | Marc Ravalomanana | ||||||||||

| • | 2009–2010 | Andry Rajoelina | ||||||||||

| Prime Minister | ||||||||||||

| • | 1992–1993 | Guy Razanamasy (first) | ||||||||||

| • | 2009–2010 | Albert Vital (last) | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | |||||||||||

| • | Upper house | Senate | ||||||||||

| • | Lower house | National Assembly | ||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||

| • | Established | September 12, 1992 | ||||||||||

| • | Constitution adopted | December 11, 2010 | ||||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||||

| • | 1992[2] | 587,040 km² (226,657 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | ||||||||||||

| • | 1992[3] est. | 12,596,263 | ||||||||||

| Density | 21.5 /km² (55.6 /sq mi) | |||||||||||

| • | 2010[4] est. | 21,281,844 | ||||||||||

| Density | 36.3 /km² (93.9 /sq mi) | |||||||||||

| Currency | Malagasy franc (until 2005) Malagasy ariary | |||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Madagascar | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

The Third Republic of Madagascar (officially called the Republic of Madagascar (Malagasy: Repoblikan'i Madagasikaray, French: République de Madagascar)) refers to the 18-year-long period in Malagasy history after the dissolution of the socialist regime in 1992.

History

A new draft constitution was approved by 75 percent of those voting in a national referendum on August 19, 1992. The first round of presidential elections followed on November 25. Frontrunner Albert Zafy won 46 percent of the popular vote as the Forces Vives candidate, and Didier Ratsiraka, as leader of his own newly created progovernment front, the Militant Movement for Malagasy Socialism (Mouvement Militant pour le Socialisme Malgache – MMSM), won approximately 29 percent of the vote. The remaining votes were split among a variety of other candidates. Because neither candidate obtained a majority of the votes cast, a second round of elections between the two frontrunners was held on February 10, 1993. Zafy emerged victorious with nearly 67 percent of the popular vote.

The Third Republic officially was inaugurated on March 27, 1993, when Zafy was sworn in as president. The victory of the Forces Vives was further consolidated in elections held on June 13, 1993, for 138 seats in the newly created National Assembly. Voters turned out in low numbers (roughly 30 to 40 percent abstained) because they were being called upon to vote for the fourth time in less than a year. The Forces Vives and other allied parties won seventy-five seats. This coalition gave Zafy a clear majority and enabled him to choose Francisque Ravony of the Forces Vives as prime minister.

By the latter half of 1994, the heady optimism that accompanied this dramatic transition process had declined somewhat as the newly elected democratic government found itself confronted with numerous economic and political obstacles. Adding to these woes was the relatively minor but nonetheless embarrassing political problem of Ratsiraka's refusal to vacate the President's Palace. The Zafy regime has found itself under increasing economic pressure from the IMF and foreign donors to implement market reforms, such as cutting budget deficits and a bloated civil service, that do little to respond to the economic problems facing the majority of Madagascar's population. Zafy also confronted growing divisions within his ruling coalition, as well as opposition groups commonly referred to as "federalists" seeking greater power for the provinces (known as "faritany") under a more decentralized government. Although spurred by the desire of anti-Zafy forces to gain greater control over local affairs, historically Madagascar has witnessed a tension between domination by the central highlanders and pressures from residents of outlying areas to manage their own affairs. In short, the Zafy regime faced the dilemma of using relatively untested political structures and "rules of the game" to resolve numerous issues of governance.

Albert Zafy was consequently impeached in 1996, and an interim president, Norbert Ratsirahonana, was appointed for the three months prior to the next presidential election. Didier Ratsiraka was then voted back into power on a platform of decentralization and economic reforms for a second term which lasted from 1996 to 2001.[5]

The contested 2001 presidential elections in which then-mayor of Antananarivo, Marc Ravalomanana, eventually emerged victorious, caused a seven-month standoff in 2002 between supporters of Ravalomanana and Ratsiraka. The negative economic impact of the political crisis was gradually overcome by Ravalomanana's progressive economic and political policies, which encouraged investments in education and ecotourism, facilitated foreign direct investment, and cultivated trading partnerships both regionally and internationally. National GDP grew at an average rate of 7 percent per year under his administration. In the later half of his second term, Ravalomanana was criticised by domestic and international observers who accused him of increasing authoritarianism and corruption.[5]

Opposition leader and then-mayor of Antananarivo, Andry Rajoelina, led a movement in early 2009 in which Ravalomanana was pushed from power in an unconstitutional process widely condemned as a coup d'état. In March 2009, Rajoelina was declared by the Supreme Court as the President of the High Transitional Authority, an interim governing body responsible for moving the country toward presidential elections. In 2010, a new constitution was adopted by referendum, establishing a Fourth Republic, which sustained the democratic, multi-party structure established in the previous constitution.[6]

See also

References

- ↑ "Madagascar: 2007 Constitutional referendum". Electoral Institute for the Sustainability of Democracy in Africa. June 2010. Archived from the original on 22 January 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ↑ The World Factbook 1992

- ↑ The World Factbook 1992

- ↑ The World Factbook 2010

- 1 2 Marcus, Richard (August 2004). "Political change in Madagascar: populist democracy or neopatrimonialism by another name?" (Occasional Paper no. 89). Institute for Security Studies. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ↑ "Madagascar: La Crise a un Tournant Critique?". International Crisis Group (in French). Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

.svg.png)