The Sword and the Rose

| The Sword and the Rose | |

|---|---|

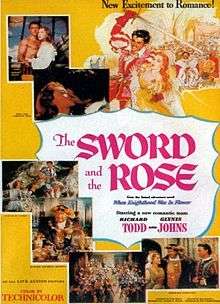

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ken Annakin |

| Produced by |

Perce Pearce Walt Disney |

| Written by |

Lawrence Edward Watkin (screenplay) Charles Major (novel "When Knighthood was in Flower") |

| Starring |

Glynis Johns James Robertson Justice Richard Todd Michael Gough Jane Barrett Peter Copley Ernest Jay Jean Mercure D. A. Clarke-Smith Gérard Oury Fernand Fabre Gaston Richer Rosalie Crutchley Bryan Coleman |

| Music by | Clifton Parker |

| Cinematography | Geoffrey Unsworth |

| Edited by | Gerald Thomas |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 92 minutes |

| Country | USA |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $1 million (US)[2] |

The Sword and the Rose is a 1953 United States family and adventure film, produced by Perce Pearce and Walt Disney and directed by Ken Annakin. The film features the story of Mary Tudor, a younger sister of Henry VIII of England.

Based on the 1898 novel When Knighthood Was in Flower by Charles Major, it was originally made into a motion picture in 1908 and again in 1922. The 1953 Disney version was adapted for the screen by Lawrence Edward Watkin. The film was shot at Denham Film Studios and was the third of Disney's British productions after Treasure Island (1950) and The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men (1952).[3] In 1956, it was broadcast on American television in two parts under the original book title.

Plot

Mary Tudor falls in love with a new arrival to court, Charles Brandon. She convinces her brother King Henry VIII to make him his Captain of the Guard. Meanwhile, Henry is determined to marry her off to the aging King Louis XII of France as part of a peace agreement. Mary's longtime suitor the Duke of Buckingham takes a dislike to Charles as he is a commoner and the Duke wants Mary for himself. However, troubled by his feelings for the princess, Brandon resigns and decides to sail to the New World. Against the advice of her lady-in-waiting Lady Margaret, Mary dresses up like a boy and follows Brandon to Bristol. Henry's men find them and throw Brandon in the Tower of London. King Henry agrees to spare his life if Mary will marry King Louis and tells her that when Louis dies she is free to marry whomever she wants. Meanwhile, Mary asks the Duke of Buckingham for help but he only pretends to help Brandon escape from the Tower, really planning to have him killed while escaping. The Duke thinks he is drowned in the Thames, but he survives.

Mary marries King Louis and encourages him to drink to excess and be active so that his already deteriorating health worsens. His heir Francis makes it clear that he will not return Mary to England after the king's death, but keep her for himself. When she goes to him for help, the Duke of Buckingham tells Lady Margaret that Brandon is dead and decides to go "rescue" Mary himself. Lady Margaret discovers that Brandon is alive and learning of the Duke's treachery they hurry back to France. Louis dies and the Duke of Buckingham arrives in France to bring Mary back to England. He tells her that Brandon is dead and tries to force her to marry him. Charles arrives in time, rescues her and kills the Duke. Mary and Brandon are married and remind Henry of his promise to let her pick her second husband. He forgives them and makes Charles Duke of Suffolk.

Cast

- Glynis Johns as Mary Tudor

- James Robertson Justice as King Henry VIII

- Richard Todd as Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk

- Michael Gough as Duke of Buckingham

- Jane Barrett as Lady Margaret

- Peter Copley as Sir Edwin Caskoden

- Ernest Jay as Lord Chamberlain

- Jean Mercure as Louis XII

- D. A. Clarke-Smith as Cardinal Wolsey

- Gérard Oury as Dauphin of France

- Fernand Fabre as DeLongueville

- Gaston Richer as Antoine Duprat

- Rosalie Crutchley as Queen Katherine

- Bryan Coleman as Earl of Surrey

- Helen Goss as Princess Claude

Production

At the end of 1948, funds from Walt Disney Pictures stranded in foreign countries, including the United Kingdom, exceeded $8.5 million. Walt Disney decided to create a studio in Britain, Walt Disney British Films Ltd. or Walt Disney British Productions Ltd. in association with RKO Pictures and started production of Treasure Island (1950). With the success of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men (1952), Disney wanted to keep the production team to make a second film; he chose The Sword and the Rose inspired by the novel When Knighthood Was in Flower (1898) by Charles Major. This team consisted of the director Ken Annakin, producer Douglas Pierce, writer Lawrence Edward Watkin, and the artistic director Carmen Dillon.[4]

At the beginning of production, Annakin and Dillon went to Burbank, Disney Studios in order to develop the script and set the stage with storyboards, a technique used by Annakin on production of Robin Hood . During this step, each time a batch of storyboards was finished, it was presented to Walt Disney who commented and brought his personal touch. Annakin was granted great freedom with the dialogue.

Walt Disney came to oversee the production of the film in the UK from June to September 1952. The team spent several months researching period details to make the film more realistic. Working in pre-production had helped reduce the need for natural settings in favor of studio sets designed by Peter Ellenshaw. Ellenshaw painted sets for 62 different scenes in total. According to Leonard Maltin, Ellenshaw's work was such that it is sometimes impossible to tell where the painting ends and reality begins.

Reception

The film's budget exceeded that of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men, but earned only $2.5 million.[5]

The film disappointed at the US box office but did better in other countries. However the relative failure of this and Rob Roy, the Highland Rogue caused Disney to become less enthusiastic about costume pictures.[6]

The film was serialized in the show The Wonderful World of Disney.[7]

Analysis

Leonard Maltin surmised that The Sword and the Rose is historically equivalent to Pinocchio (1940) although it remains primarily a dramatic entertainment featuring costumed actors. However, it was greeted coolly in the UK mainly because of its historical approximations despite reviews from The Times that said that Mary had "remarkably alive moments" and James Robertson Justice's King Henry had "a royal air". On the other side of the Atlantic in the United States the New York Times reviewed the film as "a time consuming tangle of mild satisfaction". Despite these criticisms, the team responsible for the film was reassembled for another film Rob Roy, the Highland Rogue.[8]

Peter Ellenshaw's work on set allowed him to get a "lifetime contract" with the Disney studio. He moved to the United States after the shooting of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954).

Douglas Brode draws a parallel between The Sword and the Rose and Lady and the Tramp (then in production) in which two female characters of noble lineage are enamored of a poor male character.

Steven Watts sees The Sword and the Rose and Rob Roy as showing the Disney studio's concern for individual liberty fighting against powerful social structures and governments. He is joined in this opinion by Douglas Brode. Brode sees the film and the ball scene, not as a conservative, but as an incentive to "dance crazes" (as the twist) for the American youth of the 1950s and 1960s. The ballroom dancing bears more resemblance to a dance competition in the 1950s than to a minuet of pre-Elizabethan England. Brode sees a form of rebel involvement. The proximity of the dancers, and rhythms not resemble the flip is introduced to the court by Mary Tudor near the rebellious teenager. Moreover, Henry VIII took advantage of the proximity afforded by this dance to flirt with a young lady of his court. Brode cites the reply of Mary to the older Catherine of Aragon, who is shocked by this dance: "Shall I not have what music and dances I like at my own ball?". Brode said that two years later rock and roll would similarly upset the American nation.[9]

Historical inaccuracies

There are many historical inaccuracies in the film. Charles Brandon was actually a childhood friend of King Henry and not a newcomer to court as is depicted in the film; he had already received the title of Viscount from Henry in 1513. Furthermore, the couple's aborted attempt to sail to the New World never happened; indeed, this is much of an anachronism as the earliest serious English attempts at North American colonization would only occur under Queen Elizabeth I, some fifty years later. It was Brandon and not the Duke of Buckingham who escorted Mary back to England after the death of Louis. The Duke's involvement is purely fictitious and his wife Eleanor Percy is eliminated entirely from the story. King Henry is portrayed as a middle aged and corpulent figure, although at the time he was only 23. His wife Catherine of Aragon is also shown as a brunette although she was a redhead.[10]

Game

An unrelated Amiga computer game has the same name.

See also

References

- ↑ "The Sword and the Rose: Detail View". American Film Institute. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ↑ 'The Top Box Office Hits of 1953', Variety, January 13, 1954

- ↑ British cinéma of the 1950s: the decline of deference by Sue Harper, Vincent Porter

- ↑ The Disney Studio Story by Richard Holliss, Brian Sibley

- ↑ The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney by Michael Barrier p..225

- ↑ Film Fare: Hollywood Producers Concentrate on Fewer, More Lavish Pictures Theatre Owners Complain. But Studios' Profits Are The Best in Years Genghis Khan and Ben Hur Producers Concentrate on Fewer, More Lavish Films; Theatre Owners Complain, But Studio Profits Soar BY DAVID KENYON WEBSTER Staff Reporter of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL. Wall Street Journal (1923 - Current file) [New York, N.Y] 13 July 1954: 1.

- ↑ Disney TV by J. P. Telotte p..13

- ↑ The Disney Films by Leonard Maltin 3rd Edition

- ↑ From Walt to Woodstock by Douglas Brode p..6

- ↑ Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII by David Starke