The Children's Hour (film)

| The Children's Hour | |

|---|---|

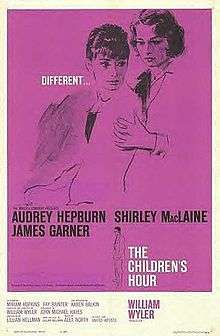

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | William Wyler |

| Produced by | William Wyler |

| Screenplay by | John Michael Hayes |

| Based on |

The Children's Hour by Lillian Hellman |

| Starring |

Shirley MacLaine Audrey Hepburn James Garner |

| Music by | Alex North |

| Cinematography | Franz Planer |

| Edited by | Robert Swink |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 107 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.6 million[1] |

| Box office | $3 million[1] |

The Children's Hour (released as The Loudest Whisper in the United Kingdom) is a 1961 American drama film directed by William Wyler. It is in effect a remake of These Three from 1936 directed by William Wyler. The screenplay by John Michael Hayes is based on the 1934 play of the same title by Lillian Hellman. The film stars Audrey Hepburn, Shirley MacLaine, and James Garner.

Plot

Former college classmates Martha Dobie (Shirley MacLaine) and Karen Wright (Audrey Hepburn) open a private school for girls. Martha's Aunt Lily (Miriam Hopkins), an aging actress, lives and teaches elocution at the school. After an engagement of two years to Joe Cardin (James Garner), a reputable obstetrician, Karen finally agrees to set a wedding date. Joe is related to the influential Amelia Tilford (Fay Bainter), whose granddaughter Mary (Karen Balkin) is a student at the school. Mary is a spoiled, conniving child who bullies her classmates, particularly Rosalie Wells (Veronica Cartwright), whom she blackmails when she discovers her in possession of a student's missing bracelet.

When Mary is caught in a lie, Karen punishes her by refusing to let her attend the weekend's boat races. Mary goes home to her grandmother and twists a story so that she will not have to return to school that day. Karen learns what the story is from a father of a departing student and confronts Amelia about Mary accusing Martha and Karen of being lovers. Mary is foiled at convincing others that she personally saw the interactions between Martha and Karen. Mary coerces Rosalie to corroborate her story. Joe is frustrated by the situation, saying that he has finished cleaning up his grandmother's home, and maintains his engagement to Karen and his friendship with Martha. The two women intend to file a suit of libel and slander against Mrs. Tilford.

Martha and Karen are isolated at the school. Aunt Lily returns after the suit has been lost because she would not return to testify on behalf of her niece and Karen. The incident had been circulated widely by the media. Joe wants to continue with his intention to marry Karen and wants Martha to restart life with them in a rural area where he has found a practice.

Karen insists that Joe tell her whether he believes that there was a relationship between Martha and Karen. Joe tells Karen that he believes it's untrue. She then says that nothing ever happened and that she could not continue with the engagement.

Rosalie's mother (Sally Brophy) discovers a cache of items among her daughter's belongings, including the bracelet inscribed to Evelyn. Mrs. Wells takes her daughter to Mrs. Tilford who, while walking over to meet her granddaughter, Mary, on the stairs collapses on the floor.

Karen tells Martha that Joe will not come back. Martha is distraught at Karen's cryptic explanation and urges her to not let Joe go. Karen, however, wants to leave town with Martha the next day. She believes they can go where they will not be recognized and can start a new life, but Martha does not. As Martha tries to talk herself into believing she and Karen are just good friends, she realizes that she does truly love Karen. While Karen does not believe her, tries to dissuade her and maintains her own heterosexuality, Martha comes to believe she has loved Karen ever since they met and that she was simply unaware of the true nature of her feelings. Despite Karen's assurances to the contrary, Martha feels responsible for ruining both their lives and is appalled by her feelings towards Karen.

Mrs. Tilford visits the two teachers. She has learned about the falsehood perpetrated by her; the court proceedings will be reversed and the award for damages settled. Karen refuses Mrs. Tilford's gesture.

Martha no longer wants to continue with the conversation. Karen leaves her for a walk on the school grounds. Aunt Lily asks Karen about the whereabouts of Martha as her door is locked. Karen breaks loose the door's slide lock with a candleholder and discovers Martha has hanged herself in her room. After Martha's funeral, Karen walks away alone, while Joe watches her from the distance.

Cast

- Shirley MacLaine as Martha Dobie

- Audrey Hepburn as Karen Wright

- James Garner as Dr. Joseph "Joe" Cardin

- Miriam Hopkins as Lily Mortar, Martha's aunt she nicknames "the duchess"

- Fay Bainter as Mrs. Amelia Tilford

- Karen Balkin as Mary Tilford, Amelia's granddaughter

- Veronica Cartwright as Rosalie Wells

- Mimi Gibson as Evelyn

- William Mims as Mr. Burton

- Sally Brophy as Mrs. Wells, Rosalie's mother

- Hope Summers as Agatha

Production

Hellman's play was inspired by the 1809 true story of two Scottish school teachers whose lives were destroyed when one of their students accused them of engaging in a lesbian relationship, but in the Scottish case, they eventually won their suit, although that did not change the devastation upon their lives.[2] At the time of the play's premiere (1934) the mention of homosexuality on stage was illegal in New York State, but authorities chose to overlook its subject matter when the Broadway production was acclaimed by the critics.[3]

The first film adaptation of the play was These Three directed by Wyler and released in 1936. Because the Hays Code, in effect at the time of the original film's production (1936), would never permit a film to focus on or even hint at lesbianism, Samuel Goldwyn was the only producer interested in purchasing the rights. He signed Hellman to adapt her play for the screen, and the playwright changed the lie about the two school teachers being lovers into a rumor that one of them had slept with the other's fiancé. Because the Production Code refused to allow Goldwyn to use the play's original title, it was changed to The Lie, and then These Three.[3]

By the time Wyler was ready to film the remake in 1961, the Hays Code had been liberalized to allow screenwriter John Michael Hayes to restore the original nature of the lie. Aside from having Martha hang rather than shoot herself as she had in the play, he remained faithful to Hellman's work, retaining substantial portions of her dialogue.

In the 1995 documentary film The Celluloid Closet, Shirley MacLaine said she and Audrey Hepburn never talked about their characters' alleged homosexuality. She also claimed Wyler cut some scenes hinting at Martha's love for Karen because of concerns about critical reaction to the film.

The film was James Garner's first after suing Warner Bros. to win his release from the television series Maverick. Wyler broke an unofficial blacklist of the actor by casting him, and Garner steadily appeared in films and television shows over the following decades, including immediately playing the lead in four different major movies released in 1963.

Miriam Hopkins, who portrays Lily Mortar in the remake, appeared as Martha in These Three.

The film's location shooting was done at the historic Shadow Ranch, in present-day West Hills of the western San Fernando Valley.[4]

Reception

Bosley Crowther of the New York Times observed,

In short, there are several glaring holes in the fabric of the plot, and obviously Miss Hellman, who did the adaptation, and John Michael Hayes, who wrote the script, knew they were there, for they have plainly sidestepped the biggest of them. They have not let us know what the youngster whispered to the grandmother that made her hoot with startled indignation and go rushing to the telephone . . . And they have not let us into the courtroom where the critical suit for slander was tried. They have only reported the trial and the verdict in one quickly tossed off line. So this drama that was supposed to be so novel and daring because of its muted theme is really quite unrealistic and scandalous in a prim and priggish way. What's more, it is not too well acted, except by Audrey Hepburn in the role of the younger of the school teachers . . . Shirley MacLaine as the older school teacher . . . inclines to be too kittenish in some scenes and do too much vocal hand-wringing toward the end . . . James Garner as the fiancé of Miss Hepburn and Miriam Hopkins as the aunt of Miss MacLaine give performances of such artificial laboring that Mr. Wyler should hang his head in shame. Indeed, there is nothing about this picture of which he can be very proud.[5]

Variety said, "Audrey Hepburn and Shirley MacLaine . . . beautifully complement each other. Hepburn's soft sensitivity, marvelous projection and emotional understatement result in a memorable portrayal. MacLaine's enactment is almost equally rich in depth and substance."[6] TV Guide rated the film 3½ out of four stars, adding "The performances range from adequate (Balkin's) to exquisite (MacLaine's)."[7]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10:

- Nominated Courtroom Drama Film[8]

Nominations

The film was nominated for five Academy Awards.[9]

- Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress (Fay Bainter)

- Academy Award for Best Black-and-White Cinematography (Franz Planer)

- Academy Award for Best Black-and-White Costume Design (Dorothy Jeakins)

- Academy Award for Best Black-and-White Art Direction (Fernando Carrere and Edward G. Boyle)

- Academy Award for Best Sound (Gordon E. Sawyer)

- Golden Globe Award for Best Actress – Motion Picture Drama (Shirley MacLaine)

- Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actress – Motion Picture (Fay Bainter)

- Golden Globe Award for Best Director

- Directors Guild of America Award for Outstanding Directing - Feature Film

See also

References

- 1 2 Balio 1987, p. 171.

- ↑ "Lesbian sex row rocked society". Edinburgh Evening News. 25 February 2009. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- 1 2 "These Three". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ↑ "Shadow Ranch Park". Laparks.org. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (15 March 1962). "The Children's Hour (1961)". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ↑ "The Children's Hour". Variety. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ↑ "The Children's Hour". TV Guide. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ↑ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-19.

- ↑ "The 34th Academy Awards (1962) Nominees and Winners". Oscars.org. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- Bibliography

- Balio, Tino (1987). United Artists: The Company that Changed the Film Industry. Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-11440-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Children's Hour. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Children's Hour |

- The Children's Hour at the Internet Movie Database

- The Children's Hour at AllMovie

- The Children's Hour at the TCM Movie Database

- The Children's Hour at Rotten Tomatoes

- James Garner interview at the Archive of American Television