The Book of the Sage and Disciple

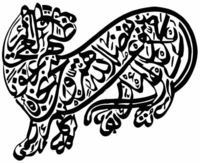

The Book of the Sage and Disciple (Arabic: كتاب العالم والغلام ; Kitāb al-‘ālim wa-l-ghulām) is a religious narrative of spiritual initiation written in the form of a dramatic dialogue by Ja‘far bin Manṣūr al-Yaman (270 AH/883 CE – c. 347 AH/958 CE). The work describes the encounter of a disillusioned young man with a dā‘ī, or Ismāʿīlī Muslim missionary, who gradually introduces his new disciple to the inner dimensions of Islam as elaborated by the Shī‘ī imāms.

Ismāʿīlī Muslims, known less commonly as Seveners, are Shī‘ī Muslims who believe that Ismāʿīl ibn Ja‘far (b. 100/719) was the true prophetic successor or imām of Ja‘far al-Sādiq (d. 148/765), as opposed to Ithnā‘asharī or Twelvers who believe that Mūsā al-Kāẓim (d. 183/799) was designated imām over his younger brother Ismāʿīl. After the ‘Abbāsid Revolution of 750 CE Ismāʿīlīs came to believe that Muḥammad ibn Ismāʿīl, son of the seventh imām and their awaited madhi, had entered a state of occultation. In his absence Ismāʿīlīs began widely propagating their faith beyond their base of power in the Levant through the institution of the da‘wa, or mission led by a dā‘ī.[1] In addition to presiding over the primary missionary activities of the da‘wa, the dā‘ī was responsible for the education, safety and spiritual health of his community. The personal relationship of the dā‘ī and his students, portrayed so vividly by Ja‘far bin Manṣūr al-Yaman in his Kitāb, would decisively influence the sheikh-murīd bond of later Sufi orders. With the rise of the Fāṭimid dynasty in the first quarter of the tenth century CE, Ismāʿīlīs identified these caliphs with their imāms.[2]

In this manner the Kitāb is to be viewed as a classic of early Fāṭimid literature, documenting important aspects of the development of the Ismāʿīlī da‘wa in tenth-century Yemen. The Kitāb is also of considerable historical value for modern scholars of Arabic prose literature as well as those interested in the relationship of esoteric Shī‘ism with early Islamic mysticism. Likewise is the Kitāb an important source of information regarding the various movements within tenth-century Shī‘ism leading to the spread of the Fāṭimid-Isma‘īlī da‘wa throughout the medieval Islamicate world, and the religious and philosophical history of post-Fāṭimid Musta‘lī branch of Ismāʿīlism in Yemen and India.[3]

The Author

Ja‘far bin Manṣūr al-Yaman was a high-ranking Ismāʿīlī poet, theologian and court companion active during the reign of the first four Fāṭimid caliphs. Born to an accomplished Shī‘ī family of Kufan origins in Yemen, Ja‘far was a son of the famous Ismāʿīlī proselytizer ibn Hawshāb (d. 302AH/914CE). As a result of his pioneering work establishing the Isma‘lī da‘wa of Yemen, ibn Hawshāb was commonly known by the laqab Manṣūr al-Yaman (“the Conqueror of Yemen”), whence derives Ja‘far's patronymic. As the only son of ibn Hawshāb to follow in his footsteps after his death, Ja‘far was often at odds with his brother Abū al-Ḥasan. Their mutual estrangement eventually forced Ja‘far to emigrate to North Africa, where he arrived during the reign of the second Faṭimid caliph al-Qā'im (r. 322-34AH/933-46CE).[4] There he witnessed the anti-Fāṭimid revolt led by Khārajī Berber Abū Yazīd, which began in the last two years of al-Qā'im's reign and ended in the first regnal year of his successor, al-Manṣūr (r. 334-41AH/946-53CE).[5][6]

Composed largely during the years 333-36AH/945-48CE, Ja‘far's poetry expressed intense loyalty toward Fāṭimid rule. Many of his compositions also contained allegorical interpretations or ta'wīl for Qurʾānic words and expressions (Sarā'ir al-nuṭaqā and Asrār al-nuṭaqā) as well as Islamic ritual worship, letters of the Arabic alphabet (Risālat ta'wīl ḥurūf al-muʿjam) and the hierarchy of the Fāṭimid daʿwa (Kitāb al-kashf, al-Shawāhid wa-l-bayān and Kitāb al-farā'iḍ wa ḥudūd al-dīn).[7]

His early work also celebrated al-Manṣūr's triumph over Abū Yazīd, currying him favor with the caliph. Indeed, Ja‘far maintained a grand residence in Manṣūriyya, a town founded by the eponymous ruler near al-Qayrawān in honor of this victory. However, later in life Ja‘far found himself in such dire financial straits that he was obliged to mortgage his household at great risk. He was in danger of total forfeiture until the fourth Fāṭimid caliph al-Mu‘izz (r. 341-65/953-75) forgave his debt in recognition of services rendered by Ja‘far and his father ibn Hawshāb. Ja‘far died five years into al-Mu‘izz's reign.[8]

The Work

The Book of the Sage and the Disciple is one of several pieces of writing attributed to Ja'far that have survived for centuries in Yemen and Gujarat, serving as an important touchestones for spiritual teaching in these communities. Written as a dramatic dialogue, the Kitāb is noteworthy evidence for the development of this literary form in the Islamicate world in a manner independent from its Greek iterations. The work also describes the development of Shī'ī religious life in the early medieval period through the proliferation of tariqa Shi'ism and the ethical and spiritual pedagogy of its hierarchical, genealogical structure of filiation and pedigree. These themes are each powerfully in evidence in Ja‘far's Kitāb, and demonstrate the manner in which distinctly Shī'ī religious life was later translated into a more widespread mystical sensibility.

The dialogue itself opens with words of gratitude toward the Sage ('ālim), who has called the community of the speaker to the true faith, has directed this community toward knowledge and instructed them in correct religious practice. The speaker asks for further clarification on these matters, and the Sage responds by enjoining obedience to his teachings as a means of thanking him, citing correct practice and leading to the path as the best forms of gratitude.

He then offers a parable for his audience about a young man whose journey toward truth takes him from material comfort to spiritual angst, finally culminating in God's illuminating for him the true path—a path which obliges the man to call others to follow him on it. This obligation has been codified in a spiritual hierarchy in which each successive link in the chain of precedence is duty-bound to bring others into the fold. Thus is the man in the parable obliged to wander through many countries as a teacher, until he comes upon a foreign community which is divided on questions of spirituality, and whose interest in religion, proximity to the true path and shared religious affiliation with Islam necessitate the man's intervention. Here he takes on a didactic role, answering questions that the individuals of this community pose to him in order to further pique their interest. The most receptive of these becomes his pupil, and he trains this acolyte in the divine argument (ḥujja) concerning the Shī'ī imams and saints (awliyā').

The Sage then commands his disciple to adhere to the outer meaning of the Qur'an (ẓāhir). Indeed, all revealed books are complementary in their divine origin, acting in a successive chain of authority mirroring the spiritual hierarchy of the sheikh-murid relationship. The Sage asks five things of his pupil: to adhere to his commands; to conceal nothing from him; to expect selectivity from the Sage in answering his questions; to wait for the Sage to broach new topics; and to hide any concerns he might have from his father. Indeed, the character of the disciple's father seems to stand in for a potentially hostile community from which Shī'ī Muslims are obligated to conceal their true beliefs for fear of violent reprisal (taqiyya).

After a period of study spent under these strictures, the disciple earns regular contact with the sheikh and delivers his oath (bay'a) to him. After this point the Sage reveals to him the inner beliefs of the Ismāʿīlī Shī'īs (bāṭin), including the esoteric interpretation of Qur'anic cosmology, which is structured along the intermediaries of prophets, imāms and saints linking human and divine.[9]

Citations

- ↑ Daftary, Farhad (1998). A Short History of the Ismailis. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 36–50.

- ↑ Daftary, Farhad (1990). The Ismāʿīlīs: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 104.

- ↑ Morris, J.W. (2001). The Master and the Disciple: an Early Islamic Spiritual Dialogue. London: IB Taurus. pp. 6–17.

- ↑ Ḥammādi, Moḥammad b. Mālek (1939). Kašf asrār al-bāṭeniya wa aḵbār al-Qarāmeṭa. Cairo.

- ↑ Haji, Hamid (2008). "Jaʿfar b. Manṣur-al-Yaman". Encyclopaedia Iranica. No. XIV: 349.

- ↑ Morris, J.W. (2005). Reason and Inspiration in Islam. London: IB Taurus. pp. 102–16.

- ↑ Poonawala, Ismail K. (1977). Biobibliography of Ismāʿīlī Literature. Malibu.

- ↑ Haji, Hamid (2008). "Jaʿfar b. Manṣur-al-Yaman". Encyclopaedia Iranica. No. XIV: 349.

- ↑ Morris, J.W. (2005). Reason and Inspiration in Islam. London: IB Taurus. pp. 102–16.

References

- Daftary, Farhad (1998). A Short History of the Ismailis. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press.

- Daftary, Farhad (1990). The Ismāʿīlīs: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Haji, Hamid (2008). “Jaʿfar b. Manṣur-al-Yaman” in Encyclopaedia Iranica Vol. XIV, Fasc. 4.

- Ḥammādi, Moḥammad b. Mālek (1939). Kašf asrār al-bāṭeniya wa aḵbār al-Qarāmeṭa, ed. Moḥammad Zāhed b. Ḥasan Kawṯari, Cairo.

- Morris, J.W. (2001). The Master and the Disciple: an Early Islamic Spiritual Dialogue. London, LB Taurus.

- –––––––– (2005) “Revisiting Religious Shi'ism and Early Sufism,” in Reason and Inspiration in Islam. Ed. T. Lawson. London: LB Tauris.

- Poonawala, Ismail K. (1977). Biobibliography of Ismāʿīlī Literature, Malibu.