The Alamo (1960 film)

| The Alamo | |

|---|---|

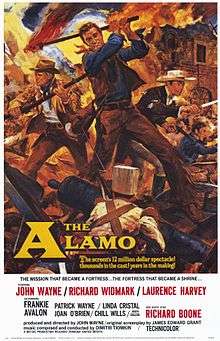

1960 Theatrical Poster by Reynold Brown | |

| Directed by | John Wayne |

| Produced by | John Wayne |

| Written by | James Edward Grant |

| Starring |

John Wayne Richard Widmark Laurence Harvey |

| Music by | Dimitri Tiomkin |

| Cinematography | William H. Clothier |

| Edited by | Stuart Gilmore |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 202 min. (roadshow version); 167 min. (general release version) |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $12 million est.[1] |

| Box office | $17.26 million(US/ Canada)[2] |

The Alamo is a 1960 American historical epic war film about the 1836 Battle of the Alamo produced and directed by John Wayne and starring Wayne as Davy Crockett. The picture also stars Richard Widmark as Jim Bowie and Laurence Harvey as William B. Travis, and the supporting cast features Frankie Avalon, Patrick Wayne, Linda Cristal, Joan O'Brien, Chill Wills, Joseph Calleia, Ken Curtis, Ruben Padilla as Santa Anna, and guest star Richard Boone as Sam Houston. The movie was photographed in 70 mm Todd-AO by William H. Clothier and released by United Artists.

Plot

The film depicts the Battle of the Alamo and the events leading up to it. Sam Houston leads the forces fighting for Texas independence and needs time to build an army. The opposing Mexican forces, led by General Santa Anna, are numerically stronger and also better armed and trained. Nevertheless, the Texans have spirit and morale remains generally high.

Lieutenant Colonel William Travis is tasked with defending the Alamo, a former mission in San Antonio. Jim Bowie arrives with reinforcements and the defenders dig in. Meanwhile, Davy Crockett arrives.

Santa Anna's armies arrive and surround the fort. The siege begins. Jim Bowie goes to Santa Anna under the peace flag, so Travis, angered by Jim Bowie, shoots a cannon at the armies, saying he will negotiate peace from a position of power only.

In a nighttime raid, the Texans sabotage the Mexicans' biggest cannon. The Texans maintain high hopes as they are told a strong force led by Colonel James Fannin is on its way to break the siege. Crockett, however, sensing an imminent attack, sends one of his younger men, Smitty, to ask Houston for help. Crockett knows this will perhaps save Smitty's life.

The Mexicans frontally attack the Alamo. The defenders hold out and kill hundreds of charging Mexican soldiers, further boosting morale, although the Texans' own losses are not insignificant. Bowie sustains a leg wound. All of the foregoing has no basis in fact, as there is no historical record of an initial frontal assault rebuffed by the defenders, and history indicates Bowie to be sick and debilitated in his quarters at this point in time. The movie then depicts morale dropping when Travis tells his men that Fannin's reinforcements have been ambushed, and, after surrendering, slaughtered by the Mexicans.

Travis chooses to stay with his command and defend the Alamo, but he gives the other defenders the option of leaving. Crockett, Bowie and their men prepare to leave, but an inspired tribute by Travis convinces them to stay and fight to the end.

On the thirteenth day of the siege, Santa Anna's artillery bombards the Alamo and kills or wounds several Texans. The entire Mexican army sweeps forward, attacking on all sides. The defenders kill dozens of charging Mexicans, but the attack is overwhelming. The Mexicans blast a hole in the Alamo wall and soldiers swarm through. Travis tries to rally the men but is shot and killed. Crockett leads the Texans in the final defense of the fort. The Mexicans take heavy losses, but swarm through and overwhelm the Texans. The Texans retreat to their final defensive positions. Crockett is killed in the chaos when he is run through by a lance and then blown up as he ignites the powder magazine. Bowie, in bed with his wound, kills several Mexicans but is bayoneted and dies. As the last Texan is killed, the Mexican soldiers discover the hiding place of the wife and child of Texan defender Captain Dickinson. The battle is over and the Mexicans have won.

Santa Anna observes the carnage and provides safe passage for Mrs. Dickinson and her child. Smitty returns too late, watching from a distance. He takes off his hat in respect and then escorts Mrs. Dickinson away from the battlefield.

The subplot follows the conflict existing among the strong-willed personalities of Travis, Bowie, and Crockett. Travis stubbornly defends his decisions as commander of the garrison against the suggestions of the other two - particularly Bowie with whom the most bitter conflict develops - as well as trying to maintain discipline amongst a force made up primarily of independently-minded frontiersmen and settlers. Crockett, well liked by both Bowie and Travis, eventually becomes a mediator between the other two as Bowie constantly threatens to withdraw his men rather than deal with Travis. Despite their personal conflicts, all three learn to subordinate their differences and in the end bind themselves together in an act of bravery to defend the fort against inevitable defeat.

Cast

- John Wayne as Col. Davy Crockett, a larger-than-life legend from Tennessee who arrives at the Alamo bringing a band of fellow adventurers to the fight.

- Richard Widmark as Col. Jim Bowie, a legendary figure like Crockett, who shares command of the Alamo with William Travis, but bears ultimate authority only over his volunteer group.

- Laurence Harvey as Col. William Barrett Travis, who shares command of the Alamo garrison with Bowie, but has ultimate authority over the regular soldiers.

- Frankie Avalon as Smitty, the youngest of the Alamo defenders, and one of Crockett's Tennesseans.

- Patrick Wayne as Capt. James Butler Bonham, a Texan officer sent out with an appeal for help.

- Linda Cristal as Graciela Carmela Maria 'Flaca' de Lopez y Vejar, a young woman whom Crockett saves from forced marriage.

- Joan O'Brien as Mrs. Sue Dickinson, wife of Captain Almaron Dickinson and cousin of Col. William Travis, who refuses to leave the fort with her young daughter.

- Chill Wills as Beekeeper, one of Crockett's colorful Tennesseans.

- Joseph Calleia as Juan Seguin, a San Antonio political figure who leads Mexican volunteers to help defend the Alamo.

- Ken Curtis as Capt. Almaron Dickinson, Travis's aide-de-camp.

- Carlos Arruza as Lt. Reyes, an officer of Santa Anna's army, sent to demand the surrender of the fort.

- Jester Hairston as Jethro, Jim Bowie's loyal slave.

- Veda Ann Borg as Blind Nell Robertson, the wife of Alamo defender Jocko Robertson.

- John Dierkes as Jocko Robertson, Nell's husband, and a Tennessean, though not one of Crockett's band.

- Denver Pyle as Thimblerig (the Gambler), one of Crockett's Tennessee volunteers.

- Aissa Wayne as Lisa Dickinson, the daughter of Almaron and Sue Dickinson.

- Hank Worden as Parson, one of Crockett's Tennessee volunteers.

- Bill Henry as Dr. Sutherland, the garrison physician.

- Bill Daniel as Col. Neill, an officer in the Texas army, and an adviser to Sam Houston.

- Wesley Lau as Emil Sande, a corrupt San Antonio businessman who attempts to force Flaca into marriage.

- Chuck Roberson as a Tennessean, one of Crockett's volunteers.

- Guinn Williams as Lt. "Irish" Finn, one of Bowie's volunteers.

- Olive Carey as Mrs. Dennison, one of the women evacuated from the Alamo prior to the battle.

- Ruben Padilla as Generalissimo Antonio Miguel Lopez de Santa Anna, the dictatorial president of Mexico and leader of the army intent on putting down the Texas revolution.

- and guest star Richard Boone as General Sam Houston, leader of the Texas army, who hopes the stand at the Alamo will gain him time to gather troops to repel Santa Anna's forces.

Background

By 1945 John Wayne had decided to make a movie about the 1836 Battle of the Alamo.[3] He hired James Edward Grant as scriptwriter, and the two began researching the battle and preparing a draft script. They hired Pat Ford, son of John Ford, as a research assistant. As the script neared completion, however, Wayne and the president of Republic Pictures, Herbert Yates, clashed over the proposed $3 million budget.[4] Wayne left Republic over the feud but was unable to take his script with him. That script was later rewritten and made into the movie The Last Command with Jim Bowie the character of focus.[5]

Production

Wayne and producer Robert Fellows formed their own production company, Batjac.[5] As Wayne developed his vision of what a movie about the Alamo should be, he concluded he did not want to risk seeing that vision changed; he would produce and direct the movie himself, though not act in it. However, he was unable to enlist financial support for the project without the presumptive box-office guarantee his on-screen appearance would provide. In 1956, he signed with United Artists; UA would contribute $2.5 million to the movie's development and serve as distributor. In exchange, Batjac was to contribute an additional $1.5–2.5 million, and Wayne would star in the movie. Wayne secured the remainder of the financing from wealthy Texans who insisted the movie be shot in Texas.[6] In an interview in the UK with Robert Robinson after the movie was finished Wayne admitted he invested $1,500,000 of his own money in the Alamo and believed it was a good investment.

Set

The movie set, later known as Alamo Village, was constructed near Brackettville, Texas, on the ranch of James T. Shahan. Chatto Rodriquez, the general contractor of the set, built 14 miles (23 km) of tarred roads for access to the set from Brackettville. His men sank six wells to provide 12,000 gallons of water each day, and laid miles of sewage and water lines. They also built 5,000 acres (2,000 ha) of horse corrals.[7]

Rodriquez worked with art designer Alfred Ybarra to create the set. Historians Randy Roberts and James Olson describe it as "the most authentic set in the history of the movies".[7] Over a million and a quarter adobe bricks were formed by hand to create the walls of the former Alamo Mission.[7] The set was an extensive three quarter-scale replica of the mission, and has since been used in 100 other westerns, including other depictions of the battle. It took more than two years to construct.

Casting

Wayne was to have portrayed Sam Houston, a bit part that would have let him focus on his first major directing effort, but investors insisted he play a leading character. He took on the role of Davy Crockett, handing the part of Houston to Richard Boone.[8] Wayne cast Richard Widmark as Jim Bowie and Laurence Harvey as William Barrett Travis.[7] Harvey was chosen because Wayne admired British stage actors and he wanted "British class". When production became tense, Harvey spoke lines from Shakespeare in a Texan accent.[9] Other roles went to family and close friends of Wayne, including his son Patrick and daughter Aissa.[10] The future western songwriter and stuntman Rudy Robbins had a bit role in the film as one of the Tennessee Volunteers.

Several days after filming began, Widmark complained he had been miscast and tried to leave. Among other things, it seemed ridiculous the diminutive 5'9" Widmark would be playing the "larger than life" Bowie, who was a reported 6'6". After threats of legal action, he agreed to finish the picture.[11] During the filming he had Burt Kennedy rewrite his lines.[12]

Sammy Davis, Jr. asked Wayne for the part of a slave as he wanted to break out of song and dance. Some producers blocked the move, apparently because Davis was dating white actress May Britt.[9]

Direction

Wayne's mentor John Ford showed up uninvited and attempted to exert undue influence on the film. Wayne sent him off to shoot unnecessary second-unit footage in order to maintain his own authority. Virtually nothing of Ford's footage was used, but Ford is often erroneously described as an uncredited co-director.[13]

According to many people involved in the film, Wayne was an intelligent and gifted director despite a weakness for the long-winded dialogue of his favorite screenwriter, James Edward Grant.[13] Roberts and Olson describe his direction as "competent, but not outstanding."[14] Widmark complained that Wayne would try to tell him and other actors how to play their parts which sometimes went against their own interpretation of characters.[9][11]

Filming

Filming began on September 9, 1959. Some actors, notably Frankie Avalon, were intimidated by rattlesnakes. Crickets were everywhere, often ruining shots by jumping on actors' shoulders or chirping loudly.[11]

A bit player, LeJean Ethridge, died in a domestic dispute during filming and Wayne was called to testify at an inquest.

Harvey forgot that a firing cannon has a recoil; during the scene in which, as Travis, he fires in response to a surrender demand, the cannon came down on his foot, breaking it — he didn't scream in pain until after Wayne had called "Cut!". Wayne praised his professionalism.[9]

Filming ended on December 15. A total of 560,000 feet of film was produced for 566 scenes. Despite the scope of the filming, it lasted only three weeks longer than scheduled. By the end of development, the film had been edited to three hours and 13 minutes.[15]

Music

The score was composed by Dimitri Tiomkin, and most famously featured the song "The Green Leaves of Summer", with music by Tiomkin and lyrics by Paul Francis Webster. The song was performed on the soundtrack by The Brothers Four, whose rendition reached #65 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart; it has since been covered by many artists.

Another known song from this film is '"Ballad of the Alamo" (with Paul Francis Webster), which was covered by Marty Robbins and Frankie Avalon.[16] Members of the Western Writers of America chose it as one of the Top 100 Western songs of all time.[17]

The original soundtrack album has been issued on Columbia Records, Varèse Sarabande, and Ryko Records. In 2010, a complete score containing newly recorded versions of Tiomkin's music was issued on Tadlow Music/Prometheus Records, as conducted by Nic Raine and played by the City of Prague Philharmonic Orchestra. This release contains previously unreleased material.

Release

Wayne hired publicist Russell Birdwell to coordinate the media campaign.[18] Birdwell convinced seven states to declare an Alamo Day and sent information to elementary schools around the United States to assist in teaching about the Alamo.[19]

In 1960, the world premiere was held at the Woodlawn Theatre in San Antonio, Texas.

Themes

Historical accuracy

The film does little to explain the causes of the Texas Revolution or why the battle took place.[20] Alamo historian Timothy Todish said "there is not a single scene in The Alamo which corresponds to a historically verifiable incident." Historians J. Frank Dobie and Lon Tinkle demanded their names be removed as historical advisors.[21]

The entire plot is full of inaccuracies:

- Bowie did not brandish a seven-barrelled volley Nock gun, nor was he wounded in the leg during the final assault, nor did his wife die during the time of the siege; he fell ill due to typhoid fever and was barely awake during the final attack, and Bowie's wife died a year before the battle was fought.

- Fannin was not ambushed and slaughtered during the siege of the Alamo; he and his men were murdered at Goliad on Palm Sunday three weeks after the Alamo fell.

- Bowie and Crockett never made the decision to leave.

- Though Bowie and Travis disliked each other intensely, they both agreed that the Alamo should be defended.

- The movie shows the final battle taking place during the day; in reality, the attack was pre-dawn, while most of the Alamo defenders were sleeping.

Despite this, the film does carry some accurate historical detail:

- It has the correct names for many of the supporting characters at the Alamo, including Captain Almaron Dickinson, played by Ken Curtis, and Susanna Dickinson, played by Joan O'Brien.

- It accurately portrays Travis as dying early on in the final assault, while defending the north wall.

- It correctly shows Bowie to be incapacitated in bed during the assault.

- It truthfully shows Susannah Dickinson as being present during the siege with her infant daughter and surviving the siege, then being allowed to leave unharmed by the Mexican army.

Politics

Wayne's daughter Aissa wrote, "I think making The Alamo became my father's own form of combat. More than an obsession, it was the most intensely personal project in his career."[18] Many of Wayne's associates agreed that the film was a political platform for Wayne. Many of the statements that his character made reflected Wayne's anti-communist views. To be sure, there is an overwhelming theme of freedom and the right of individuals to make their own decisions. One may point to a scene in which Wayne, as Crockett, remarks: "Republic. I like the sound of the word. Means that people can live free, talk free, go or come, buy or sell, be drunk or sober, however they choose. Some words give you a feeling. Republic is one of those words that makes me tight in the throat."[18]

The film draws elements from the Cold War environment in which it was produced. According to Roberts and Olson, "the script evokes parallels between Santa Anna's Mexico and Khruschchev's Soviet Union as well as Hitler's Germany. All three demanded lines in the sand and resistance to death."[18]

Many of the minor characters, at some point during the film, speak about freedom and/or death, and their sentiments may have reflected Wayne's own viewpoint.

Response

Though the film had a large box-office take, its cost kept it from being a success and Wayne lost his personal investment. He sold his rights to United Artists, which had released it, and it made back its money.

Critical response was mixed, from the New York Herald Tribune's four-star "A magnificent job...Visually and dramatically, The Alamo is top-flight," to Time magazine's "flat as Texas."[22] Years later, Leonard Maltin criticized the script as being "full of historical name-dropping and speechifying," but praised the climactic battle scene.

The film has a score of 50% on Rotten Tomatoes.[23]

The film is thought to have been denied awards because Academy voters were alienated by an overblown publicity campaign, particularly one Variety ad claiming that the film's cast was praying harder for Chill Wills to win his award than the defenders of the Alamo prayed for their lives before the battle. The ad, placed by Wills, reportedly angered Wayne, who took out an ad of his own deploring Wills's tastelessness. In response to Wills's ad, claiming that all the voters were his "Alamo Cousins," Groucho Marx took out a small ad which simply said, "Dear Mr. Wills, I am delighted to be your cousin, but I voted for Sal Mineo," (Wills's rival nominee for Exodus).[24]

The film's cost, more than its poor attendance, was at the root of its initial presumed failure, and indeed, it has retained popularity with many people. The soundtrack album has been in print continuously for fifty years. References to The Alamo show up in several spoofs and homages. During the opening credits of Midnight Cowboy, Joe Buck (Jon Voight) walks past a dilapidated theater displaying the film's title on its crumbling marquee. Mad magazine features a spoof in its June 1961 issue ("Mad visits John Wayde on the set of 'At the Alamo'"). The film is mentioned by Vic Fontaine (James Darren) in the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine episode "Badda-Bing, Badda-Bang". The singer describes it as having great battle scenes and nice sets, but with an excessive running time. An American Werewolf in London contains extended dialogue about The Alamo. Viva Max!, shot at the actual Alamo in San Antonio, makes numerous comedic references to the film with the Reynold Brown film poster painting featured.

Wayne provided a clip of the film for use in How the West Was Won. Despite being anachronistic (How the West Was Won begins in 1839 and the Alamo fell in 1836), the clip occurs near the beginning of the second half of the film, as Spencer Tracy narrates the events that led up to the American Civil War.

Awards and honors

The Alamo won the Academy Award for Best Sound (Gordon E. Sawyer, Fred Hynes) and was nominated for Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Chill Wills), Best Cinematography (Color), Best Film Editing (Stuart Gilmore), Best Music (Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture) (Dimitri Tiomkin), Best Music (Song) (Dimitri Tiomkin and Paul Francis Webster for The Green Leaves of Summer), and Best Picture (John Wayne, producer).[25] Its successful bid for several Oscar nominations over such films as Psycho and Spartacus was largely due to intense lobbying by producer John Wayne.[26]

Dimitri Tiomkin won the best original score Golden Globe award. The movie was selected by the National Board of Review as one of the year's ten best films. The picture won the Bronze Wrangler award as the best theatrical motion picture of the year from the Western Heritage Awards.

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2003: AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains:

- Davy Crockett – Nominated Hero[27]

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores – Nominated[28]

- 2006: AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – Nominated[29]

Different versions

The Alamo premiered at its 70mm roadshow length of 202 minutes, including overture, intermission, and exit music, but was severely cut for wide release. UA re-edited it to 167 minutes. The 202-minute version was believed lost until a Canadian fan, Bob Bryden, realized he had seen the full version in the 1970s. He and Alamo collector Ashley Ward discovered the last known surviving print of the 70mm premiere version in Toronto.[30] It was pristine. MGM (UA's sister studio) used this print to make a digital video transfer of the roadshow version for VHS and LaserDisc release.

The print was taken apart and deteriorated in storage. By 2007 it was unavailable in any useful form. MGM used the shorter general release version for subsequent DVD releases. At present, the only existing version of the original uncut roadshow release is on standard definition 480i digital video. It is the source for broadcasts on Turner Classic Movies. The best available actual film elements are of the 35mm negatives of the general release version.

A restoration of the deteriorating print found in Toronto, supervised by Robert A. Harris, was envisaged but to date is not underway.[31] The version endangered is the 70mm uncut roadshow version (202 min). The cut down 167-minute version still exists in decent condition in 35mm.

In 2014, an Internet campaign was formed urging MGM to restore The Alamo from the deteriorating 70mm elements. This garnered some publicity from KENS-TV in San Antonio, and attention from filmmakers such as J.J. Abrams, Matt Reeves, Rian Johnson, Guillermo del Toro, Alfonso Cuaron, and Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu.[32][33] In his 2014 biography of Wayne, John Wayne: The Life and Legend author Scott Eyman states that the full-length Toronto print has deteriorated to the point where it is now unusable.[34]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Sheldon Hall, Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History Wayne State University Press, 2010 p 161

- ↑ "All-time top film grossers", Variety 8 January 1964 p 37. Please note this figure is rentals accruing to film distributors not total money earned at the box office..

- ↑ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 260.

- ↑ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 261.

- 1 2 Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 262.

- ↑ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 263.

- 1 2 3 4 Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 264.

- ↑ Clark, Donald, & Christopher P. Andersen. John Wayne's The Alamo: The Making of the Epic Film (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1995) ISBN 0-8065-1625-9

- 1 2 3 4 John Wayne — The Man Behind The Myth by Michael Munn, published by Robson Books, 2004

- ↑ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 265.

- 1 2 3 Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 266.

- ↑ pp. 146-147 Joyner, C. Courtney Burt Kennedy Interview in The Westerners: Interviews with Actors, Directors, Writers and Producers McFarland, 14/10/2009

- 1 2 Clark, Donald, & Christopher P. Andersen. John Wayne's The Alamo: The Making of the Epic Film, Carol: 1995

- ↑ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 268.

- ↑ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 269.

- ↑ William R. Chemerka, Allen J. Wiener: Music of the Alamo. Bright Sky Press, 2009. p. 118, 151

- ↑ Western Writers of America (2010). "The Top 100 Western Songs". American Cowboy. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 271.

- ↑ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 272.

- ↑ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 270.

- ↑ Todish et al. (1998), p. 188.

- ↑ quoted in Ashford, Gerald. On the Aisle, San Antonio Express and News, November 5, 1960, p. 16-A

- ↑ The Alamo - Rotten Tomatoes

- ↑ Levy, Emanuel. Oscar Scandals: Chill Wills http://www.emanuellevy.com/article.php?articleID=822

- ↑ "The 33rd Academy Awards (1961) Nominees and Winners", oscars.org, retrieved 2011-08-22

- ↑ Dirks, Tim. http://www.filmsite.org/aa60.html

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-13.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-13.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-13.

- ↑ Bryden, Bob, The Finding of the 'Lost' Alamo Footage'

- ↑ Harris, Robert A., The Reconstruction and Restoration of John Wayne's THE ALAMO

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Eyman, Scott. John Wayne: The Life and Legend (Simon & Schuster, April 1, 2014) ISBN 978-1-4391-9958-9

References

- Roberts, Randy; Olson, James S. (2001). A Line in the Sand: The Alamo in Blood and Memory. The Free Press. ISBN 0-684-83544-4.

- Todish, Timothy J.; Todish, Terry; Spring, Ted (1998). Alamo Sourcebook, 1836: A Comprehensive Guide to the Battle of the Alamo and the Texas Revolution. Austin, TX: Eakin Press. ISBN 978-1-57168-152-2.

Additional reading

- Clark, Donald, & Christopher P. Andersen. John Wayne's The Alamo: The Making of the Epic Film (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1995) ISBN 0-8065-1625-9

- Farnsworth, Rodney. "John Wayne's Epic of Contradictions: The Aesthetic and Rhetoric of Way and Diversity in The Alamo" Film Quarterly, Vol. 52, No. 2 (Winter 1998-1999), p. 24 - 34

- "Dust to Dust" by Robert Wilonsky. Dallas Observer, August 9, 2001

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Alamo (1960 film) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Alamo (1960 film). |

- The Alamo at the Internet Movie Database

- The Alamo at the TCM Movie Database

- The Alamo at AllMovie

- Alamo Sentry: The Popular Culture of The Alamo

- "On the Set of The Alamo": Behind-the-scenes footage from the production of the film in Brackettville. From the Texas Archive of the Moving Image.

- Comparison between the Theatrical Version and the Director's Cut http://www.movie-censorship.com/report.php?ID=3869