Tenagino Probus

| Vir Perfectissimus Tenagino Probus | |

|---|---|

| Born | Northeast Italy (?) |

| Died |

end 270 AD Babylon, Egypt province |

| Cause of death | Heroic suicide |

| Nationality | Italian (?) |

| Citizenship | Roman |

| Occupation | Soldier (general officer): Equestrian governor of Numidia and then Aegyptu |

| Employer | Emperors Gallienus & Claudius II |

| Known for | Campaigns in Africa Proconsularis (?) and the Eastern Mediterranean and resistance to takeover of Egypt by Zenobia |

| Opponent(s) | Septiminus Zabdas |

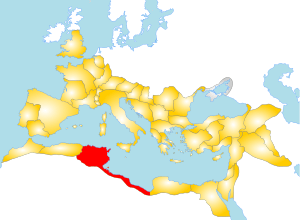

Tenagino Probus was a Roman soldier and procuratorial official whose career reached its peak at the end of the sixth decade of the third century AD (c. 255-260). A poverty of primary sources means that nothing is known for certain of his origins or early career. However, in later years he served successively as Praeses (governor) of the province of Numidia (i.e. Praeses Numidiae) and of Egypt, (i.e. Praefectus Aegypti). These were both very senior procuratorial offices, the latter in particular traditionally considered one of the pinnacles of an equestrian career. In these roles he exercised military skills in addition to administrative ones; as Praefectus Aegypti he led military operations outside his province. He died resisting the invasion of Egypt by the forces of Zenobia of Palmyra in the troubled inter-regnum between Emperors Claudius II and Aurelian.

Despite the limited availability of information about Probus,[lower-alpha 1] the fact that he was: (i) entrusted with the government of two of the Empire's most economically and strategically significant provinces; and (ii) given important military command outside his province (at least during his time as Praefectus Aegypti) indicates that he had the reputation of a highly competent Imperial functionary. His known appointments suggest that both Emperor Gallienus and Gallienus' successor Claudius II held him in high regard. Probus was likely among the relatively small group of professional soldiers who benefited from the opening up of provincial governorships and senior military commands, which were previously reserved for senators.

Primary Sources

Literary

Probus is referred to by the Historia Augusta (SHA) in the Uita Divi Claudii[1] under the name "Probatus." In the garbled account in the Uita Probi recounting the campaigns of Marcus Aurelius Probus in North Africa and Egypt, the future emperor is credited with actions that other, more reliable, sources indicate should be attributed to Tenagino Probus.[2] The SHA mentions him only as a military commander, making no reference to his procuratorial status in Numidia or Egypt.

Among Greek and Byzantine sources, Zosimus' Nova Historia records in fair detail Probus' military exploits during the period when he was Praefectus Aegypti, without actually identifying him by name. The text makes no reference to his earlier appointment in Numidia. George Syncellus[3] and Zonaras[4] largely reiterate Zosimus, with some confusion of the material.

Epigraphic

A number of epigraphic inscriptions attest to the existence of Tenagino Probus and some details of his career.

- In Latin, from Lambaesis, Numidia (now Lambèse, Tunisia).[5] Dated to 267-8 AD in the principate of Gallienus.[6] Probus is not mentioned by name, but the context suggests that the inscription relates to his term of office, an interpretation authoritative commentators generally accept.[6]

- In Latin, from Colonia Marciana Ulpia Traiana Thamugadi, Numidia (now Timgad, Algeria).[7] This inscription names Probus, refers to him as praeses, and invokes the Emperor Claudius. It likely dates from soon after Claudius' accession to the purple in mid-268 AD, but before his election as consul for 269 AD at end-268.[8]

- In Latin, from Thuburbo Maius, Numidia, (now Henchir-Kasbat, Tunisia).[9] This inscription refers to Probus as governor of the province and patronus of the colonia. The colonia referred to is probably Thurburbo Maius. The date is 269 AD, under Claudius.[10]

- In Greek, from Claudiopolis (more usually known as Cyrene, Libya).[11] The inscription refers to Probus as a diasemotatos (i.e. Vir Perfectissimus) and Praefectus Aegypti and invokes Claudius II as Emperor. It celebrates the victory gained by the Romans under Probus over Berber nomads in the neighbouring province of Cyrenaica. The inscription is usually assigned to late 269/early 270 AD.[12]

Origins and early career

Origins

No literary or epigraphic evidence exists to shed light on Probus' origins.

Onomastic analysis of his nomen (i.e. his family name) suggests that "Tenagino" was quite rare. Only two occurrences of the name are recorded, both in northeast Italy: Tenigenonia (sic) Claudia;[13] and Q. Tenagino Maximus.[14] These inscriptions might indicate that Probus originated in this region, but are not conclusive. However, Probus' nomen does indicate that his family's citizen-status pre-dated the Constitutio Antoniniana of 212 AD. This may mean that the family were people of substance.

Early career

No available information speaks to Probus' early career. Some evidence indicates long-term military service, but it is unknown whether he was already of equestrian status when he enlisted in the army.[lower-alpha 2]

Probus's first known gubernatorial appointment was as Praeses Numidiae. Until at least 260 AD, and possibly even later, Numidia had been a propraetorial province, i.e. it had been governed on behalf of the Emperor by a senatorial Legatus Augusti (an official who had previously held office in Rome or elsewhere as a praetor[lower-alpha 3]). However, the epigraph from Lambaesis, Numidia, (above) indicates that by 267 AD (during the sole reign of the Emperor Gallienus), the governor of Numidia was officially titled praeses. (The title praeses did not always indicate that a governor was of equestrian rank, but in the case of Numidia he was, as were all known subsequent governors of that province.) As noted, it is now generally assumed that Probus was the official referred to in that inscription, even though his name has disappeared from the text. Indeed, he may have been Numidia's first equestrian governor. Therefore, it is highly likely that Probus was an early beneficiary of Gallienus' policy of giving equestrians military commands (over legions) and administrative posts (as governors of propraetorial provinces) that, prior to Gallienus' sole reign (260-268 AD), had been reserved almost exclusively for men of senatorial status.

Procuratorial career

Praeses Numidiae

The function

The loyalty of the Praeses Numidiae was important to whomever governed the Roman Empire for a number of reasons:

- Numidia was one of the main sources of grain and olive oil, essential staples of the Roman diet, making the area a key resource underpinning the emperor's ability to control Rome and supply the armies stationed in Europe.

- The governor of Numidia commanded the Legio III Augusta based at Lambaesis, the only significant military force in Roman north Africa (which spanned from the boundaries of Egypt to the Atlantic coast of Morocco). This legion was ostensibly meant to defend the north African provinces from the nomad populations on its southern boundaries, but for the most part this task was, arguably, not suited to a unit whose chief strength was its heavy infantry. The legion was an instrument at both too powerful and too blunt for that job.[15] Instead, the strategic vision of the Imperial government seems to indicate that the chief role of the governor of Numidia as head of his legion was to uphold the Empire's authority, both in Numidia and in the entirety of the resource-rich African region, particularly the neighboring province of Africa Proconsularis. During the reign of Gallienus and his successors, Africa Proconsularis rivaled Egypt itself as a granary of Rome.[lower-alpha 4] In this sense, the Emperor regarded the governor of Numidia as his "man-on-the spot" in Africa, and the legion commanded by the governor as the ultimate sanction of the Empire's ability to exploit the region's strategic and economic benefits for the Empire's own purposes.[lower-alpha 5]

- After the loss of the western provinces to the "Gallic Emperor" Postumus and the de facto secession of the eastern provinces under Odenathus of Palmyra, the Numidian garrison constituted the only substantial reserve of military manpower available to Gallienus in Europe as he faced the Scythian inroads of 267-8.[lower-alpha 6]

For these reasons, Probus' appointment as Praeses Numidiae demonstrates that he had established a reputation for competence and earned Gallienus' trust.

Probus in office

No reliable information exists about Probus' period of office in Numidia.

The SHA suggests that, like his predecessor during the regime of Maximinus Thrax, Probus may have been called upon to intervene in Africa Proconsularis to put down an insurrection in Carthago.[2] However, the balance of academic opinion is that this story the sort of invention in which the SHA seems to delight and should, therefore, be rejected.[lower-alpha 7] The same passage in the uita goes on to assert that "Probus" slew a "certain Aradio" - no further explanation - in single combat before honoring him with a magnificent tomb. This too is generally rejected,[18] although some authorities are prepared to concede that it may be authentic.[19]

Praefectus Aegypti

Strategic significance of Egypt

As noted, the epigraph from Claudiopolis (above) is generally interpreted to mean that Probus had taken on the role of Praefectus Aegypti before the end of 269 AD.

Ever since Augustus' conquest of Egypt in the first century BC, the emperors of Rome had regarded their absolute control of this territory and its grain harvests as a sine qua non for the maintenance of their authority. Loss of control of Egypt would almost immediately undermine the Imperial government's ability to maintain control of the Roman people. The Emperor's absolute trust in the praefectus of Egypt was considered even more vital than that of the praefecti of the African provinces. Therefore, from the principate's earliest days, its praefectus had always been an equestrian, presumably because most equestrians lacked a personal power base comparable to a senator's, making equestrians more likely to remain loyal to the princeps. When Claudius II appointed Probus to this office, he demonstrated that he (Claudius) had the utmost confidence in Probus, even though Probus had been a protegé of Claudius' predecessor Gallienus.

Probus' term as praefectus

Claudius II further demonstrated his confidence in Probus shortly after Probus assumed the praefecture of Egypt, when Claudius commissioned him to intervene militarily in the neighboring senatorial province of Creta et Cyrenaica, which had suffered an incursion by the Marmaritae. The Marmaritae were, evidently, a nomadic people who roamed the semi-desert territory known as the Marmarica, which lay west of the Siwa Oasis in western Egypt and to the south of Cyrenaica. Traditionally, Emperors hesitated to allow governors to undertake military action beyond the boundaries of their own province. However, as demonstrated in Numidia, forces stationed in Imperial provinces could be deployed in neighboring provinciae inermes (lit. unarmed provinces) when necessary, and the text of the epigraph from Claudiopolis (above) suggests that the Marmaritae were increasingly becoming a nuisance in Cyrenaica. The epigraph refers to the Marmaritae's "audacity"[lower-alpha 8] and suggests that Probus dealt with the incursion with effective dispatch - although, as was always the case, the victory was officially attributed to the reigning Emperor (i.e. Claudius). In the inscription, Cyrene is referred to as Claudiopolis (i.e. "City of Claudius") in the Emperor's honor, although it is unclear whether this was intended to celebrate the defeat of the Marmaritae.

Shortly after Probus' success in Cyrenaica, Claudius gave him a further commission to undertake a naval campaign against Gothic pirates who had been raiding the islands of the eastern Mediterranean and the southern coast of Asia Minor. Only Zosimus records this action.[21] However, recent archaeological discoveries in the Turkish province of Antalya suggest that, even as Claudius was concluding his war against the Scythian migrants in the Balkans, he had dispatched an expeditionary force under Lucius Aurelius Marcianus to repel attacks by Gothic pirates along the southern coasts of Asia Minor. It is thought that this force cooperated with Probus' naval force. Zosimus reports that the pirates were driven away "without achieving much" - an outcome that he attributes entirely to the efforts of Probus, but which was more likely the result of a combined operation.[lower-alpha 9]

Final campaign and death

Zosimus contains the fullest account of Probus' final campaign and death.

While Probus was away fighting the pirates at sea, Zenobia began a drive to extend her authority over Asia, Arabia and Egypt. One Timagenes, otherwise unknown, led a strong pro-Palmyrene faction in the population (and possibly in the Imperial garrison) in encouraging the targeting of Egypt in particular. In support of Timagenes, Zenobia's general Septiminus Zabdas invaded the province at the head of an army of 70,000 men and, together with his local allies, defeated the Egyptian loyalists who had mustered an army of 50,000. Zabdas then returned to Syria, leaving behind a garrison of 5,000, presumably in Alexandria.

When this news reached Probus, he returned to Egypt with the force he had led against the pirates and, with the support of those sympathetic to the Imperialist cause in Egypt, drove out Zabdas' garrison. Zabdas returned, but he was again defeated by Probus, the pro-Imperial Egyptian forces and "soldiers from Africa" - no further explanation. Probus then seems to have followed Timagenes upriver to the fortress of Babylon (located at the head of the Nile delta, now a suburb of modern Cairo), thus cutting off the enemy's escape route to Syria. However, using his knowledge of the surrounding country, Timagenes seized the summit of a nearby mountain with 2,000 men and, launching a surprise attack on Probus' army, defeated it utterly.[lower-alpha 10] Probus was captured and, in the Roman heroic tradition, chose to kill himself rather than bear the ignominy of defeat.[lower-alpha 11]

The Uita Divi Claudii broadly repeats this account, but describes Timagenes a Palmyrene general rather than an anti-Imperialist Egyptian.

Papyrological and numismatic evidence suggests that Zabdas began his assault on Egypt in the autumn of 270 AD and by the end of the year had brought it firmly under the control of his mistress Zenobia.[22]

Notes

- ↑ Throughout this article Tenagino Probus is referred to by his cognomen Probus, according to the practice of both Latin and Greek/Byzantine sources, except where it is necessary to distinguish him from others with the same name.

- ↑ For examples of the various ways in which a soldier might enter the equestrian career-path, see Publius Aelius Aelianus, Lucius Petronius Taurus Volusianus, Traianus Mucianus and Lucius Aurelius Marcianus.

- ↑ Major provinces that, unlike Numidia lacked a legionary garrison - i.e. provinciae inermes - were defined as provinciae proconsulares and, as such, were nominally governed by officials appointed by the Roman Senate from among the Viri Consulares, i.e. senators who had held the office of Consul. In practice the senate's choice of governor had to be ratified by the Emperor, but the choices were always drawn from this small group of men.

- ↑ At the time of Probus' tenure, over a century had passed since a Special Grain Commission under C. Arrius Pacatus had first organized an African grain-fleet to relieve a threatened famine in Italy.[16]

- ↑ Just 30 years prior to Probus' tenure, the then-Legatus Numidiae had acted on behalf of the Emperor Maximinus Thrax to crush an uprising of the Roman settlers in Africa Proconsularis that was sparked off by the heavy sur-taxes the Emperor had imposed to finance wars against the nascent Alamanni in Germany. The garrison of Numidia thus brought to an end the short-lived principates of Gordian I and Gordian II, who had secured the backing of the Roman Senate.

- ↑ For details of the Scythian incursions that began in 267 AD, see Battle of Naissus and Lucius Aurelius Marcianus.

- ↑ The account of the purported rebellion in Carthago is suspect in part because it appears in a passage in which the author appears to have confused Tenagino Probus with his contemporary, Marcus Aurelius Probus, the future emperor, and attributed to the latter actions known from other, more reliable sources, to have been undertaken by the former. Furthermore, the specific reference to the rebellion in Carthago is not supported by any other source - always a good reason for suspecting authority of the SHA. Finally, the reference seems to have been inserted in support of a topos repeated later in the Vita Probi that, as a commander, Probus (the Emperor) never allowed his soldiers to become idle - a trait that was to contribute to the mutiny that resulted in his death.[17]

- ↑ For a discussion of Rome's attitude toward the nomadic peoples of north Africa in general terms, see Shaw.[20]

- ↑ For a discussion of a possible combined operation against the Gothic pirates in the eastern Mediterranean and Asia Minor involving sea and land forces, see Lucius Aurelius Marcianus.

- ↑ The mountain is unidentified, but may have been the site of modern Cairo Citadel.

- ↑ For further evidence of the survival of this tradition into the third century AD, see Aurelius Heraclianus.

Citations

- ↑ SHA VC(11.1 f.

- 1 2 VP(9.1-5).

- ↑ Syncellus(721).

- ↑ Zonaras(12.27).

- ↑ CIL VIII 2571 + 18057 (Lambaesis).

- 1 2 PLRE(Probus, Tenagino 1).

- ↑ (AE 1936 #58.

- ↑ PLRE(Probus. Tenagino, 2.)

- ↑ ILAlg II 24 = AE 1941 #33.

- ↑ PLRE: Probus, Tenagino 3.

- ↑ SEG IX 9 = AE 1934 #257

- ↑ PLRE: Probus, Tenagino 4 and Barnes(1972:168).

- ↑ CIL V 3345 (Verona)

- ↑ Pais 715 name(Anauni).

- ↑ Shaw(1995:IX, passim).

- ↑ Shaw(1995:I.61).

- ↑ Vita Probi 20.2.

- ↑ e.g. Barnes(1972:168).

- ↑ e.g. Saunders(1992:428).

- ↑ Shaw(1995:VII,25-46).

- ↑ Zosimus: Nova Historia: I:44.2.

- ↑ Saunders(1992:152-5).

Works cited

Abbreviations of works of reference

- SHA - The Augustan History: Life of the Deified Claudius Vita Divi Claudii (SHA VC) ); Life of Probus Vita Probi (SHA VP) );

- AE - L'Année Épigraphique; R. Cagnat et al (eds.); Paris; 1889-;

- PIR(2) - Prosopographia imperii Romani; E.Groag et al (eds.); Berlin; 1933-;

- PLRE - The prosopography of the later Roman Empire; Jones, A.H.M., Martindale, J.R. and Morris, J. (eds.);Cambridge University Press; 1971-1992.

Primary sources

- Syncellus - Mosshammer, A.A. (1984). Georgii Syncelli Ecloga Chronogaphica. Leipzig. (Syncelllus);

- Zonaras - Pinder, M. (1841–1897). Ioannis Zonarae Annales. CSHB 29-31. Bonn. (Zonaras);

- Zosumus - Paschoud, F. (1971–86). Zosimus, Histoire Nouvelle (Books 1-5). Paris. (Zosimus)

Secondary sources

- Barnes, T.D. (1972). "Some persons in the Historia Augusta". Phoenix. 26: 140–182. doi:10.2307/1087714. (Barnes(1972);

- Saunders, Randall Titus (1992). A biography of the Emperor Aurelian. Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346: UMI Dissertation Services.(Saunders(1992));

- Shaw, B.D. (1995). Rulers, Christians and Nomads in Roman North Africa. Aldershot (Hants.) and Brookfield (Vermont 05036): VARIORUM.;