Ten Great Campaigns

The Ten Great Campaigns (Chinese: 十全武功; pinyin: shí quán wǔ gōng) were a series of military campaigns launched by the Qing Empire of China in the mid–late 18th century during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735–96). They included three to enlarge the area of Qing control in Central Asia: two against the Dzungars (1755–57) and the pacification of Xinjiang (1758–59). The other seven campaigns were more in the nature of police actions on frontiers already established: two wars to suppress Jinchuan rebels in Sichuan, another to suppress rebels in Taiwan (1787–88), and four expeditions abroad against the Burmese (1765–69), the Vietnamese (1788–89), and the Gurkhas in Nepal on the border between Tibet and India (1790–92), with the last counting as two.

Campaigns against the Dzungars and the pacification of Xinjiang (1755–59)

| First Campaign against the Dzungars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Surrender of Dawachi Khan in 1755 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Qing dynasty | Dzungar Khanate | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Qianlong Emperor Bandi (Overall Command) Zhaohui (Assistant Commander) Emin Khoja Amursana Burhān al-Dīn Khwāja-i Jahān | Dawachi (POW) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

9,000 Manchu Eight Bannermen 19,500 Inner Mongols 6,500 Outer Mongols 2,000 Zunghars 5,000 Uyghurs from Hami and Turfan 12,000 Chinese | 7,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

Of the ten campaigns, the final destruction of the Dzungars (or Zunghars)[1] was the most significant. The 1755 Pacification of Dzungaria and the later suppression of the Revolt of the Altishahr Khojas secured the northern and western boundaries of Xinjiang, eliminated rivalry for control over the Dalai Lama in Tibet, and thereby eliminated any rival influence in Mongolia. It also led to the pacification of the Islamicised, Turkic-speaking southern half of Xinjiang immediately thereafter.[2]

In 1752, Dawachi and the Khoit-Oirat prince Amursana competed for the title of Khan of the Dzungars. Dawachi defeated Amursana various times and gave him no chance to recover. Amursana was thus forced to flee with his small army to the Qing imperial court. The Qianlong Emperor pledged to support Amursana since Amursana accepted Qing authority; among those who supported Amursana and the Chinese were the Khoja brothers Burhān al-Dīn and Khwāja-i Jahān. In 1755, Qianlong sent the Manchu general Zhaohui, who was aided by Amursana, Burhān al-Dīn and Khwāja-i Jahān, to lead a campaign against the Dzungars. After several skirmishes and small scale battles along the Ili River, the Qing army led by Zhaohui approached Ili (Gulja) and forced Dawachi to surrender. Qianlong appointed Amursana as the Khan of Khoit and one of four equal khans – much to the displeasure of Amursana, who wanted to be the Khan of the Dzungars.

| Second Campaign against the Dzungars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Battle of Oroi-Jalatu in 1758, Zhao Hui ambushes Amursana at night. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Qing dynasty | Dzungars loyal to Amursana | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Qianlong Emperor Bandi †(1757) (Overall Command until death in battle) Cäbdan-jab (Overall Command) Zhaohui (Assistant Commander) Ayushi Emin Khoja Burhān al-Dīn Khwāja-i Jahān |

Amursana Chingünjav † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

10,000 Bannermen 5,000 Uyghurs from Turfan and Hami Plus Zunghars | 20,000 Dzungars | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | everyone defeated except for 50 men of Chingünjav who fled | ||||||

In the summer of 1756, Amursana started a Dzungar revolt against the Chinese with the help of Prince Chingünjav. The Qing Empire reacted at the start of 1757 and sent General Zhaohui with support from Burhān al-Dīn and Khwāja-i Jahān. Among several battles, the most important ones were illustrated in Qianlong's paintings. The Dzungar leader Ayushi defected to the Qing side and attacked the Dzungar camp at Gadan-Ola (Battle of Gadan-Ola).

General Zhaohui defeated the Dzungars in two battles: the Battle of Oroi-Jalatu (1758) and the Battle of Khurungui (1758). In the first battle, Zhaohui attacked Amursana's camp at night; Amursana was able to fight on until Zhaohui received enough reinforcements to drive him away. Between the time of Oroi-Jalatu and Khurungui, the Chinese under Prince Cabdan-jab defeated Amursana at the Battle of Khorgos (known in the Qianlong engravings as the "Victory of Khorgos"). At Mount Khurungui, Zhaohui defeated Amursana in a night attack on his camp after crossing a river and drove him back. To commemorate Zhaohui's two victories, Qianlong had the Puning Temple of Chengde constructed, home to the world's tallest wooden sculpture of the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara and hence its alternate name, the 'Big Buddha Temple'. Afterwards, Huojisi of Turfan submitted to the Qing Empire. After all of these battles, Amursana fled to Russia (where he died) while Chingünjav fled north to Darkhad but was captured at Wang Tolgoi and executed in Beijing.

| Campaign in Altishahr (Pacification of Xinjiang) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Battle of Qurman 1759, Fude and Machang bring 600 troops to relieve Zhaohui in the Black River. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Qing dynasty |

Altishahri followers of the Khoja brothers Kyrgyzs Dzungar rebels | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Qianlong Emperor Zhaohui (Overall Command) Fude (Assistant Commander) Agui Doubin Rongbao Zhanyinbao Fulu Shuhede Mingrui Arigun Machang Namjil † Yan Xiangshi Yisamu Duanjibu Khoja Emin Khoja Si Bek Sultan Shah of Badakhshan |

Khwāja-i Jahān POW Burhān al-Dīn POW | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

10,000 Bannermen Uyghurs from Hami, Turfan and Badakshan Plus Zunghars | 30,000 Altishahr (Tarim Basin) Uyghurs | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

After the second campaign against the Dzungars in 1758, two Altishahr nobles, the Khoja brothers Burhān al-Dīn and Khwāja-i Jahān, started a revolt against the Qing Empire. Apart from the remaining Dzungars, they were also joined by the Kyrgyz peoples and the Oases Turkic peoples (Uyghurs) in Altishahr (the Tarim Basin). After capturing several towns in Altishahr, there were still two rebel fortresses at Yarkand and Kashgar at the end of 1758. Uyghur Muslims from Turfan and Hami, including Emin Khoja and Khoja Si Bek, remained loyal to the Qing Empire and helped the Qing regime fight the Altishahri Uyghurs under Burhān al-Dīn and Khwāja-i Jahān. Zhaohui unsuccessfully besieged Yarkand and fought an indecisive battle outside the city; this engagement is historically known as the Battle of Tonguzluq. Zhaohui instead took other towns east of Yarkand but was forced to retreat; the Dzungar and Uyghur rebels laid siege to him at the Siege of Black River (Kara Usu). In 1759, Zhaohui asked for reinforcements, 600 troops showed up and were under the overall command of generals Fude and Machang with the 200 cavalry led by Namjil; other high-ranking officers included Arigun, Doubin, Duanjibu, Fulu, Yan Xiangshi, Janggimboo, Yisamu, Agui and Shuhede. On 3 February 1759, over 5,000 enemy cavalry led by Burhān al-Dīn ambushed the 600 relief troops at the Battle of Qurman. The Uyghur and Dzungar cavalry were stopped by the Qing zamburak artillery camels, musketry and archers; Namjil and Machang led a cavalry charge on one of the flanks. Namjil was killed while Machang was unseated from horseback and was forced to fight on foot with his bow. After a hard fought battle, the Qing forces emerged victorious and attacked the Dzungar camp, causing the Dzungars besieging the Black River to withdraw. After the victory at Qurman, the Qing army overran the remaining rebel towns. Mingrui led a detachment of cavalry and defeated Dzungar cavalry at the Battle of Qos-Qulaq. The Uyghurs retreated from Qos-Qulaq but were defeated by Zhaohui and Fude at the Battle of Arcul (Altishahr) on September 1, 1759. The rebels were defeated again at the Battle of Yesil Kol Nor. After these defeats, Burhān al-Dīn and Khwāja-i Jahān fled with their small army of supporters to Badakhshan. Sultan Shah of Badakhshan promised to protect them but he contacted the Qing Empire and promised to turn them over. When the fleeing rebels came to the Sultan's capital, he attacked them and captured them. When the Qing army showed up at Sultan Shah's capital, he handed over the captured rebels to them and submitted to the Qing Empire.

Suppression of the Jinchuan hill peoples (1747–49, 1771–76)

| First Campaign against Jinchuan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

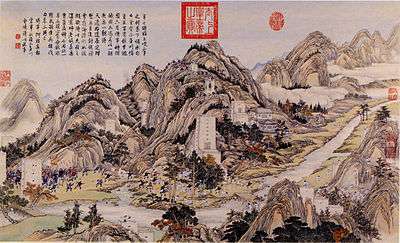

Depiction of Qing troops on a campaign in Jinchuan ("Gold Stream") | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Qing Empire | Jinchuan tribes | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Qianlong Emperor Zhang Guangsi (Overall Command) (Executed by Qianlong) Naqin (Assistant Commander) (Executed by Qianlong) Fuheng (Overall Command) Zhaohui (Assistant Commander) |

Slob Dpon Tshe Dbang | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Second Campaign against Jinchuan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Qing general Fuk'anggan assaults Luobowa mountain tower | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Qing Empire | Jinchuan tribes | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Qianlong Emperor Agui (Overall Command) Fuk'anggan (Assistant Commander) Fude (Executed by Qianlong in 1776) Wenfu † |

Sonom Senggesang | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 8,000 | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

The suppression of the Jinchuan hill peoples was the costliest and most difficult, and also the most destructive. Jinchuan (lit. "Golden Stream") was located northwest of Chengdu in western Sichuan. The tribal peoples there were related to the Tibetans of the Amdo. The first campaign in 1747–1749 was a simple affair; with little use of force the Qing army induced the native chieftains to accept a peace plan, and departed.

Interethnic conflict brought Qing intervention back after 20 years. The result was the Qing forces being forced to fight a protracted war of attrition costing the Imperial Treasury several times the amounts expended on the earlier conquests of the Dzungars and Xinjiang. The resisting tribes retreated to their stone towers and forts in steep mountains and could only be dislodged by cannon fire. The Qing generals were ruthless in annihilating the rebellious tribes, then reorganised the region in a military prefecture and repopulated it with more cooperative inhabitants.[2] When victorious troops returned to Beijing, a celebratory hymn was sung in their honour. A Manchu version of the hymn was recorded by the French Jesuit Jean Joseph Marie Amiot and sent to Paris.[3]

Campaigns in Burma (1765–69)

The Qianlong Emperor launched four invasions of Burma between 1765 and 1769. The war claimed the lives of over 70,000 Qing soldiers and four commanders,[4] and is sometimes described as "the most disastrous frontier war that the Qing dynasty had ever waged",[5] and one that "assured Burmese independence and probably the independence of other states in Southeast Asia".[6] The successful Burmese defence laid the foundation for the present-day boundary between Myanmar and China.[4]

At first, Qianlong envisaged an easy war, and sent in only the Green Standard troops stationed in Yunnan. The Qing invasion came as the majority of Burmese forces were deployed in the Burmese invasion of the Siamese Ayutthaya Kingdom. Nonetheless, battle-hardened Burmese troops defeated the first two invasions of 1765 and 1766 at the border. The regional conflict now escalated to a major war that involved military maneuvers nationwide in both countries. The third invasion (1767–1768) led by the elite Manchu Bannermen nearly succeeded, penetrating deep into central Burma within a few days' march from the capital, Ava.[7] However, the Bannermen of northern China could not cope with unfamiliar tropical terrains and lethal endemic diseases, and were driven back with heavy losses.[4] After the close-call, King Hsinbyushin redeployed most of the Burmese armies from Siam to the Chinese border. The fourth and largest invasion got bogged down at the frontier. With the Qing forces completely encircled, a truce was reached between the field commanders of the two sides in December 1769.[5][8]

The Qing forces kept a heavy military lineup in the border areas of Yunnan for about one decade in an attempt to wage another war while imposing a ban on inter-border trade for two decades. The Burmese were also preoccupied with another impending invasion by the Qing Empire, and kept a series of garrisons along the border. 20 years later, Burma and the Qing Empire resumed a diplomatic relationship in 1790. To the Burmese, the resumption was on equal terms. However, the Qianlong Emperor unilaterally interpreted the act as Burmese submission, and claimed victory.[5] Ironically, the main beneficiaries of this war were the Siamese. After having lost their capital Ayutthaya to the Burmese in 1767, they regrouped in the absence of large Burmese armies, and reclaimed their territories in the next two years.[7]

Pacification of Taiwan (1786–88)

In 1786, the Qing-appointed Governor of Taiwan, Sun Jingsui, discovered and suppressed the anti-Qing Tiandihui (Heaven and Earth Society). The Tiandihui members gathered Ming loyalists, and their leader Lin Shuangwen proclaimed himself king. Many important people took part in this revolt and the insurgents quickly rose to 50,000 people. In less than a year, the rebels occupied almost the entire part of southern Taiwan. Hearing that the rebels had occupied most of Taiwan, Qing troops were sent to suppress them in a hurry. The east insurgents defeated the poorly organised troops and had to resist falling to the enemy. Finally, the Qing imperial court sent Fuk'anggan while Hailancha, Counsellor of the Police, deployed nearly 3,000 people to fight the insurgents. These new troops were well equipped, disciplined and had combat experience which proved enough to rout the insurgents. The Ming loyalists had lost the war and their leaders and remaining rebels hid among the locals.

Lin Shuangwen, Zhuang Datian and other Tiandihui leaders had started a rebellion which at first was successful, and as many as 300,000 took part in the rebellion. The Qing general Fuk'anggan was sent to quell the rebellion with a force of 20,000 soldiers, which he accomplished. The campaign was relatively expensive for the Qing government, although Lin Shuangwen and Zhuang Datian were both captured. After the revolt ended, the Qianlong Emperor was forced to rethink the method of government for Taiwan.

The Manchu Aisin Gioro Prince Abatai's daughter was married to the Han Chinese General Li Yongfang 李永芳.[9][10] The offspring of Li received the "Third Class Viscount" (三等子爵; sān děng zǐjué) title.[11] Li Yongfang was the great great great grandfather of Li Shiyao 李侍堯 who during Qianlong's reign was involved in graft and embezzlement, demoted of his noble title and sentenced to death, however his life was spared and he regained his title after assisting in the Taiwan campaign.[12][13]

Campaigns against the Gurkhas (1788–93)

The campaigns against the Gurkhas displayed the Qing imperial court's continuing sensitivity to conditions in Tibet. The late 1760s saw the creation of a strong state in Nepal and the involvement in the region of a new foreign power, the British Empire, through the British East India Company. The Gurkha rulers of Nepal decided to invade southern Tibet in 1788.

The two Manchu resident agents in Lhasa (Ambans) made no attempt at defence or resistance. Instead, they took the child Panchen Lama to safety when the Nepalese troops came through and plundered the rich monastery at Shigatse on their way to Lhasa. Upon hearing of the first Nepalese incursions, the Qianlong Emperor ordered troops from Sichuan to proceed to Lhasa and restore order. By the time they reached southern Tibet, the Gurkhas had already withdrawn. This counted as the first of two wars with the Gurkhas.

In 1791, the Gurkhas returned in force. Qianlong urgently dispatched an army of 10,000. It was made up of around 6,000 Manchu and Mongol forces supplemented by tribal soldiers under the general Fuk'anggan, with Hailancha as his deputy. They entered Tibet from Xining in the north, shortening the march but making it in the dead of winter 1791–92, crossing high mountain passes in deep snow and cold. They reached central Tibet in the summer of 1792 and within two or three months could report that they had won a decisive series of encounters that pushed the Gurkha armies across the crest of the Himalayas and back into the valley of Kathmandu. Fuk'anggan fought on into 1793, when he forced the battered Gurkhas to sign a treaty on Qing terms which forced them to pay tribute to the Qing Empire every five years.[2]

Campaign in Vietnam (1788–89)

For most of Vietnamese history, the Vietnamese rulers sometimes recognised the Chinese emperor as their feudal lord while ruling independently in their own land. This had been the case throughout the reign of the Later Lê dynasty. This changed, however, when the brothers of Tây Sơn, leading a national uprising, defeated the feuding Trịnh and Nguyễn lords and overthrew the last Lê ruler, Lê Chiêu Thống.

Lê Chiêu Thống fled to the Qing Empire and appealed to the Qianlong Emperor for help. In 1788, a large Qing army was sent south to restore Lê Chiêu Thống to the throne. They succeeded in taking Thăng Long (present-day Hanoi) and restoring Lê Chiêu Thống on the throne, but many of his supporters were angered by their subservient position. Lê Chiêu Thống was treated as a vassal king by the Qianlong Emperor and all edicts had to be authorised by the Qing government before becoming official. In any event, the situation did not last long as the Tây Sơn leader, Nguyễn Huệ, launched a surprise attack against the Qing forces while they were celebrating the Chinese New Year in 1789. The Qing forces were unprepared but fought for five days before being defeated at Battle of Đống Đa. Lê Chiêu Thống fled back to the Qing Empire while Nguyễn Huệ was proclaimed "Emperor Quang Trung".[14] Although Nguyễn Huệ won the battle, he eventually chose to submit himself as a vassal to the Qing Empire and agreed to pay tribute annually. This strategic move was to avoid retaliation and for the greater benefit of trading with the Qing Empire.

Campaigns in perspective

In his later years, the Qianlong Emperor referred to himself with the grandiose style name of "Old Man of the Ten Completed [Great Campaigns]" (十全老人). He also wrote an essay enumerating the victories in 1792 entitled Record of Ten Completions (十全记).[15]

The campaigns were a major financial drain on the Qing Empire, costing more than 151 million silver taels.[16]

- The tribes at Jinchuan numbered less than 30,000 households and took five years to pacify.

- Nearly 1.5 million piculs (1 picul = 100 catties) of cargo were transported for the campaign in Taiwan.

- Instead of restoring Lê Chiêu Thống to the throne as the campaign in Vietnam was intended, the Qianlong Emperor ended up making peace with the new Tây Sơn dynasty and even arranged for marriages between the imperial families of Qing and Tây Sơn.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ten Great Campaigns. |

See also

References

- ↑ "Encyclopædia Britannica online entry on Kazakhstan, page 19 of 22". Britannica.com. 1991-12-16. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- 1 2 3 F.W. Mote, Imperial China 900–1800 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 936–939

- ↑ "Manchu hymn chanted at the occasion of the victory over the Jinchuan Rebels". Manchu Studies Group. 2012-12-18. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- 1 2 3 Charles Patterson Giersch (2006). Asian borderlands: the transformation of Qing China's Yunnan frontier. Harvard University Press. pp. 101–110. ISBN 0674021711.

- 1 2 3 Yingcong Dai (2004). "A Disguised Defeat: The Myanmar Campaign of the Qing Dynasty". Modern Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press: 145. doi:10.1017/s0026749x04001040.

- ↑ Marvin C. Whiting (2002). Imperial Chinese Military History: 8000 BC – 1912 AD. iUniverse. pp. 480–481. ISBN 978-0-595-22134-9.

- 1 2 DGE Hall (1960). Burma (3rd ed.). Hutchinson University Library. pp. 27–29. ISBN 978-1-4067-3503-1.

- ↑ GE Harvey (1925). History of Burma. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd. pp. 254–258.

- ↑ http://www.lishiquwen.com/news/7356.html

- ↑ http://www.fs7000.com/wap/?9179.html

- ↑ Evelyn S. Rawski (15 November 1998). The Last Emperors: A Social History of Qing Imperial Institutions. University of California Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-520-92679-0.

- ↑ http://www.dartmouth.edu/~qing/WEB/LI_SHIH-YAO.html

- ↑ http://12103081.wenhua.danyy.com/library1210shtml30810106630060.html

- ↑ A History of Vietnam: From Hong Bang to Tu Duc, Chapter 6 The Nguyen Hue Epic, pages 153–159, by Oscar Chapuis, Greenwood Publishing Group (1995), ISBN 0-313-29622-7

- ↑ Monarchy in the Emperor's Eyes: Image and Reality in the Ch`ien-lung Reign. by Harold L. Kahn, The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 31, No. 2 (Feb., 1972), pp. 393–394

- ↑ Zhuang Jifa, Qing Gaozong Shiquan Wugong Yanjiu (Taipei, 1982), p.494. (庄吉发, 《清高宗十全武功研究》)