Telstar

|

The original Telstar had a roughly spherical shape. | |

| Operator | NASA |

|---|---|

| COSPAR ID | 1962-029A |

| SATCAT № | 00340 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Bell Labs |

| Launch mass | 171 kilograms (377 lb) |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 08:35:00, July 10, 1962 |

| Rocket | Thor-Delta |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral LC-17 |

| End of mission | |

| Deactivated | February 21, 1963 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Medium Earth orbit |

| Perigee | 952 kilometres (592 mi) |

| Apogee | 5,933 kilometres (3,687 mi) |

| Inclination | 44.8° |

| Period | 2 hours and 37 minutes |

| Epoch | 1962-07-10 08:35:00 UTC |

Telstar is the name of various communications satellites. The first two Telstar satellites were experimental and nearly identical. Telstar 1 launched on top of a Thor-Delta rocket on July 10, 1962. It successfully relayed through space the first television pictures, telephone calls, and fax images, and provided the first live transatlantic television feed. Telstar 2 launched May 7, 1963. Telstar 1 and 2—though no longer functional—still orbit the Earth.[1]

Description

|

|

Belonging to AT&T, the original Telstar was part of a multi-national agreement among AT&T (USA), Bell Telephone Laboratories (USA), NASA (USA), GPO (United Kingdom) and the National PTT (France) to develop experimental satellite communications over the Atlantic Ocean. Bell Labs held a contract with NASA, paying the agency for each launch, independent of success.

The American ground station—built by Bell Labs—was Andover Earth Station, in Andover, Maine. The main British ground station was at Goonhilly Downs in southwestern England. The BBC, as international coordinator, used this location. The standards 525/405 conversion equipment (filling a large room) was researched and developed by the BBC and located in the BBC Television Centre, London. The French ground station was at Pleumeur-Bodou (48°47′10″N 3°31′26″W / 48.78611°N 3.52389°W) in north-western France.

The satellite was built by a team at Bell Telephone Laboratories that included John Robinson Pierce, who created the project;[3] Rudy Kompfner, who invented the traveling-wave tube transponder that the satellite used;[3][4] and James M. Early, who designed its transistors and solar panels.[5] The satellite is roughly spherical, measures 34.5 inches (876.30 mm) in length, and weighs about 170 pounds (77 kg). Its dimensions were limited by what would fit on one of NASA's Delta rockets. Telstar was spin-stabilized, and its outer surface was covered with solar cells capable of generating 14 watts of electrical power.

The original Telstar had a single innovative transponder that could relay data, a single television channel, or multiplexed telephone circuits. Since the spacecraft spun, it required an array of antennas around its "equator" for uninterrupted microwave communication with Earth. An omnidirectional array of small cavity antenna elements around the satellite's "equator" received 6 GHz microwave signals to relay back to ground stations. The transponder converted the frequency to 4 GHz, amplified the signals in a traveling-wave tube, and retransmitted them omnidirectionally via the adjacent array of larger box-shaped cavities. The prominent helical antenna received telecommands from a ground station.

Launched by NASA aboard a Delta rocket from Cape Canaveral on July 10, 1962, Telstar 1 was the first privately sponsored space launch. A medium-altitude satellite, Telstar was placed in an elliptical orbit completed once every 2 hours and 37 minutes, inclined at an angle of approximately 45 degrees to the equator, with perigee about 952 kilometres (592 mi) from Earth and apogee about 5,933 kilometres (3,687 mi) from Earth[6] This is in contrast to the 1965 Early Bird Intelsat and subsequent satellites that travel in circular geostationary orbits.[6]

Due to its non-geosynchronous orbit, Telstar's availability for transatlantic signals was limited to the 20 minutes in each 2.5 hour orbit when the satellite passed over the Atlantic Ocean. Ground antennas had to track the satellite with a pointing error of less than 0.06 degrees as it moved across the sky at up to 1.5 degrees per second.

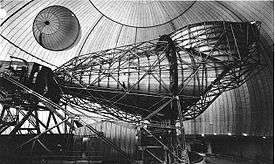

Since the transmitters and receivers on Telstar were not powerful, ground antennas had to be huge. Bell Laboratory engineers designed a large horizontal conical horn antenna with a parabolic reflector at its mouth that re-directed the beam. This particular design had very low sidelobes, and thus made very low receiving system noise temperatures possible. The aperture of the antennas was 3,600 square feet (330 m2). The antennas were 177 feet (54 m) long and weighed 380 short tons (340,000 kg). Morimi Iwama and Jan Norton of Bell Laboratories were in charge of designing and building the electrical portions of the azimuth-elevation system that steered the antennas. The antennas were housed in radomes the size of a 14-story office building. Two of these antennas were used, one in Andover, Maine, and the other in France at Pleumeur-Bodou. The GPO antenna at Goonhilly Downs in Great Britain was a conventional 26-meter-diameter paraboloid.

In service

Telstar 1 relayed its first, and non-public, television pictures—a flag outside Andover Earth Station—to Pleumeur-Bodou on July 11, 1962.[7] Almost two weeks later, on July 23, at 3:00 p.m. EDT, it relayed the first publicly available live transatlantic television signal.[8] The broadcast was made possible in Europe by Eurovision and in North America by NBC, CBS, ABC, and the CBC.[8] The first public broadcast featured CBS's Walter Cronkite and NBC's Chet Huntley in New York, and the BBC's Richard Dimbleby in Brussels.[8] The first pictures were the Statue of Liberty in New York and the Eiffel Tower in Paris.[8] The first broadcast was to have been remarks by President John F. Kennedy, but the signal was acquired before the president was ready, so engineers filled the lead-in time with a short segment of a televised game between the Philadelphia Phillies and the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field.[8][9][10] The batter, Tony Taylor, was seen hitting a ball pitched by Cal Koonce to the right fielder George Altman. From there, the video switched first to Washington, DC; then to Cape Canaveral, Florida; to the Seattle World's Fair; then to Quebec and finally to Stratford, Ontario.[8] The Washington segment included remarks by President Kennedy,[9] talking about the price of the American dollar, which was causing concern in Europe. When Kennedy denied that the United States would devalue the dollar it immediately strengthened on world markets; Cronkite later said that "we all glimpsed something of the true power of the instrument we had wrought."[8][11]

That evening, Telstar 1 also relayed the first telephone call transmitted through space, and it successfully transmitted faxes, data, and both live and taped television, including the first live transmission of television across an ocean from Andover, Maine, US to Goonhilly Downs, England and Pleumeur-Bodou, France.[12] (An experimental passive satellite, Echo 1, had been used to reflect and redirect communications signals two years earlier, in 1960.) In August 1962, Telstar 1 became the first satellite used to synchronize time between two continents, bringing the United Kingdom and the United States to within 1 microsecond of each other (previous efforts were only accurate to 2,000 microseconds).[13]

Telstar 1, which had ushered in a new age of the commercial use of technology, became a victim of technology during the Cold War. The day before Telstar 1 launched, a U.S. high-altitude nuclear bomb (called Starfish Prime) had energized the Earth's Van Allen Belt where Telstar 1 went into orbit. This vast increase in a radiation belt, combined with subsequent high-altitude blasts, including a Soviet test in October, overwhelmed Telstar's fragile transistors.[14][15][16] It went out of service in November 1962, after handling over 400 telephone, telegraph, facsimile and television transmissions.[9] It was restarted by a workaround in early January 1963.[17] The additional radiation associated with its return to full sunlight once again caused a transistor failure, this time irreparably, and Telstar 1 went out of service on February 21, 1963.

Experiments continued, and by 1964, two Telstars, two Relay units (from RCA), and two Syncom units (from the Hughes Aircraft Company) had operated successfully in space. Syncom 2 was the first geosynchronous satellite and its successor, Syncom 3, broadcast pictures from the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo. The first commercial geosynchronous satellite was Intelsat I ("Early Bird") launched in 1965.

Newer Telstars

Subsequent Telstar satellites were advanced commercial geosynchronous spacecraft that share only their name with Telstar 1 and 2.

The second wave of Telstar satellites launched with Telstar 301 in 1983, followed by Telstar 302 in 1984 (which was renamed Telstar 3C after it was carried into space by Shuttle mission STS-41-D),[18] and by Telstar 303 in 1985.

The next wave, starting with Telstar 401, came in 1993; which was lost in 1997 due to a magnetic storm, and then Telstar 402 was launched but destroyed shortly after in 1994.[19] It was replaced in 1995 by Telstar 402R, eventually renamed Telstar 4.

Telstar 10 was launched in China in 1997 by APT Satellite Company, Ltd.

In 2003, Telstars 4–8 and 13 — Loral Skynet's North American fleet — were sold to Intelsat. Telstar 4 suffered complete failure prior to the handover. The others were renamed the Intelsat Americas 5, 6, etc. At the time of the sale, Telstar 8 was still under construction by Space Systems/Loral, and it was finally launched on June 23, 2005, by Sea Launch.

Telstar 18 was launched in June 2004 by Sea Launch. The upper stage of the rocket underperformed, but the satellite used its significant stationkeeping fuel margin to achieve its operational geostationary orbit. It has enough on-board fuel remaining to allow it to exceed its specified 13-year design life.

See also

References

- ↑ "1962-ALPHA EPSILON 1". US Space Objects Registry. 2013-06-19. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- ↑ "Felker Talking Telstar". WNYC. Retrieved 2016-10-31.

- 1 2 Gavaghan, Helen (1998). Something New Under the Sun: Satellites and the Beginning of the Space Age. Springer. ISBN 0-387-94914-3.

- ↑ Sivan, Leo (1994). Microwave Tube Transmitters. Springer. ISBN 0-412-57950-2.

- ↑ Markoff, John (2004-01-19). "James Early, Engineer, 81; Helped Create A Transistor". Obituaries. The New York Times.

- 1 2 An Introduction to Satellite Communications, page 3, D. I. Dalgleish, 1989

- ↑ "IEEE History Center: First Transatlantic Transmission of a Television Signal via Satellite, 1962". IEEE History Center. 2002. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Walter Cronkite. "Telstar". NPR. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- 1 2 3 Clary, Gregory (2012-07-13). "50th anniversary of satellite Telstar celebrated". Light Years (blog). CNN. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- ↑ "Philadelphia Phillies vs Chicago Cubs". Box Score. Baseball-Almanac.com. 1962-07-23. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- ↑ Telstar, Kennedy, and World Gold & Currency Markets, YouTube

- ↑ Video: A Day in History. Telstar Brings World Closer, 1962/07/12 (1962). Universal Newsreel. 1962. Retrieved 2012-02-20.

- ↑ "Significant Achievements in Space Communications and Navigation, 1958-1964" (PDF). NASA-SP-93. NASA. 1966. pp. 30–32. Retrieved 2009-10-31.

- ↑ Glover, Daniel R. (2005-04-12). "TELSTAR". NASA Experimental Communications Satellites. Retrieved 2007-09-01.

- ↑ Early, James M. (1990). "Telstar I - Dawn of a New Age". Southwest Museum of Engineering, Communications and Computation. Retrieved 2012-07-11.

- ↑ Mayo, J.S.; et al. (July 1963). "The Command System Malfunction of the Telstar Satellite" (PDF). Bell System Technical Journal. 42: 1631–1657. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1963.tb04044.x. Archived from the original on 2013-08-10. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ↑ Lorenz, Ralph D.; Harland, David Michael (2005). Space Systems Failures: Disasters and Rescues of Satellites, Rocket and Space Probes. Springer. ISBN 0-387-21519-0.

- ↑ "NASA - STS-41D". Nasa.gov. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- ↑ "SAT ND". SAT ND. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

External links

- Walter Cronkite on the first broadcast using Telstar from the July 23, 2002, episode of All Things Considered

- May 1962 National Geographic magazine article on Telstar from porticus.org

- Telstar 1: First Private Communication Satellite - 1963 Educational Documentary on YouTube

- Stamps and envelopes related to Telstar I from the National Postal Museum

- Real-Time tracking of Telstar 1 from n2yo.com

- Official provider's page for Telstar 11N from IMS