Telex

The telex network is a switched network of teleprinters similar to a telephone network, for the purposes of sending text-based messages. The term refers to the network, not the teleprinters; point-to-point teleprinter systems had been in use long before telex exchanges were formed starting in the 1930s. Teleprinters evolved from telegraph systems, and like the telegraph they used the presence or absence of a pre-defined level of current to represent the mark or space symbols. This is as opposed to the analog telephone system, which used differing voltages to encode frequency information. For this reason, telex exchanges were entirely separate from the telephone system, with their own signalling standards, exchanges and system of "telex numbers" (the counterpart of a telephone number). When telephone and telex exchange equipment was co-located, which was not uncommon, the different signalling systems would sometimes cause interference.

Telex provided the first common medium for international record communications using standard signalling techniques and operating criteria as specified by the International Telecommunication Union. Customers on any telex exchange could deliver messages to any other, around the world. To lower line usage, telex messages were normally first encoded onto paper tape and then read into the line as quickly as possible. The system normally delivered information at 50 baud or approximately 66 words per minute encoded using the International Telegraph Alphabet No. 2. In the late days of the telex networks, end-user equipment was often replaced by modems and phone lines as well, reducing the telex network to what was effectively a directory service running on the phone network.

Development

Telex began in Germany as a research and development program in 1926 that became an operational teleprinter service in 1933. The service, operated by the Reichspost (Reich postal service)[1] had a speed of 50 baud — approximately 66 words per minute.

Telex service spread within Europe and (particularly after 1945) around the world.[2] By 1978, West Germany and West Berlin together had 123,298 telex connections. Long before automatic telephony became available, most countries, even in central Africa and Asia, had at least a few high-frequency (shortwave) telex links. Often, government postal and telegraph services (PTTs) initiated these radio links. The most common radio standard, CCITT R.44 had error-corrected retransmitting time-division multiplexing of radio channels. Most impoverished PTTs operated their telex-on-radio (TOR) channels non-stop, to get the maximum value from them.

The cost of TOR equipment has continued to fall. Although the system initially required specialised equipment, as of 2016 many amateur radio operators operate TOR (also known as RTTY) with special software and inexpensive hardware to adapt computer sound cards to short-wave radios.[3]

Modern "cablegrams" or "telegrams" actually operate over dedicated telex networks, using TOR whenever required.

Telex served as the forerunner of modern fax, email, and texting - both technically and stylistically. Abbreviated English (like "CU L8R" for "see you later") as used in texting originated with telex operators exchanging informal messages in real time — they became the first "texters" long before the introduction of mobile phones. Telex users could send the same message to several places around the world at the same time, like email today, using the Western Union InfoMaster Computer. This involved transmitting the message via paper tape to the InfoMaster Computer (dial code 6111) and specifying the destination addresses for the single text. In this way, a single message could be sent to multiple distant Telex and TWX machines as well as delivering the same message to non-Telex and non-TWX subscribers via Western Union Mailgram.

Operation and applications

Telex messages are routed by addressing them to a telex address, e.g., "14910 ERIC S", where 14910 is the subscriber number, ERIC is an abbreviation for the subscriber's name (in this case Telefonaktiebolaget L.M. Ericsson in Sweden) and S is the country code. Solutions also exist for the automatic routing of messages to different telex terminals within a subscriber organization, by using different terminal identities, e.g., "+T148".

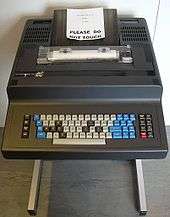

A major advantage of telex is that the receipt of the message by the recipient could be confirmed with a high degree of certainty by the "answerback". At the beginning of the message, the sender would transmit a WRU (Who aRe yoU) code, and the recipient machine would automatically initiate a response which was usually encoded in a rotating drum with pegs, much like a music box. The position of the pegs sent an unambiguous identifying code to the sender, so the sender could verify connection to the correct recipient. The WRU code would also be sent at the end of the message, so a correct response would confirm that the connection had remained unbroken during the message transmission. This gave telex a major advantage over group 2 fax which had no inherent error-checking capability.

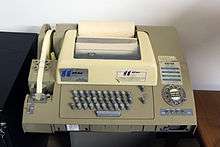

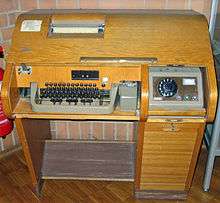

The usual method of operation was that the message would be prepared off-line, using paper tape. All common telex machines incorporated a 5-hole paper-tape punch and reader. Once the paper tape had been prepared, the message could be transmitted in minimum time. Telex billing was always by connected duration, so minimizing the connected time saved money. However, it was also possible to connect in "real time", where the sender and the recipient could both type on the keyboard and these characters would be immediately printed on the distant machine.

Telex could also be used as a rudimentary but functional carrier of information from one IT system to another, in effect a primitive forerunner of Electronic Data Interchange. The sending IT system would create an output (e.g., an inventory list) on paper tape using a mutually agreed format. The tape would be sent by telex and collected on a corresponding paper tape by the receiver and this tape could then be read into the receiving IT system.

One use of telex circuits, in use until the widescale adoption of X.400 and Internet email, was to facilitate a message handling system, allowing local email systems to exchange messages with other email and telex systems via a central routing operation, or switch. One of the largest such switches was operated by Royal Dutch Shell as recently as 1994, permitting the exchange of messages between a number of IBM Officevision, Digital Equipment Corporation ALL-IN-1 and Microsoft Mail systems. In addition to permitting email to be sent to telex, formal coding conventions adopted in the composition of telex messages enabled automatic routing of telexes to email recipients.

Telex in Canada

Canada-wide automatic teleprinter exchange service was introduced by the CPR Telegraph Company and CN Telegraph in July 1957 (the two companies, operated by rivals Canadian National Railway and Canadian Pacific Railway, would join to form CNCP Telecommunications in 1967). This service supplemented the existing international telex service that was put in place in November 1956. Canadian telex customers could connect with nineteen European countries in addition to eighteen Latin American, African, and trans-Pacific countries.[4] The major exchanges were located in Montreal (01), Toronto (02), and Winnipeg (03).[5]

Telex in the United Kingdom

Telex began in the UK as an evolution from the 1930s Telex Printergram service, appearing in 1932 on a limited basis. This used the telephone network in conjunction with a Teleprinter 7B and signalling equipment to send a message to another subscriber with a Teleprinter, or to the Central telegraph Office.

In 1945 as the traffic increased it was decided to have a separate network for Telex traffic and the first manual exchange opened in London. By 1954 the public inland Telex service opened via manually switched exchanges. A number of subscribers were served via automatic sub-centres based on Post Office relays and Type 2 Uniselectors acting as concentrators for the manual exchange.

In the late 1950s the decision was made to convert to automatic switching and it was completed by 1961, based on 21 exchanges, spread across the country, with one international exchange, based in London. The equipment used the Strowger system for switching, as was the case for the telephone network. Conversion to Stored Programme Control (SPC) began in 1984 using exchanges made by Canadian Marconi with the last Strowger exchange closing in 1992. User numbers increased over the following years into the 1990s.

The dominant supplier of the Telex machine themselves was Creed (later ITT Creed).

A separate service "Secure Stream 300" (prev. Circuit Switched Data Network) was a variant of Telex running at 300 baud, used for telemetry and monitoring purposes by utility companies and banks, as example. This was a high security virtual private wire system with a high degree of resilience through diversely routed dual path network configurations

In 2004 British Telecom stopped offering the Telex service to new customers and discontinued the service in 2008, allowing users to transfer to Swiss Telex if they wished to continue to use Telex.

Telex in the United States

Teletypewriter eXchange

The Teletypewriter eXchange Service (TWX) was developed by the AT&T Corporation in the United States and originally ran at 45.45 baud or approximately 60 words per minute, using five level Baudot code. AT&T began TWX on November 21, 1931.[6][7] AT&T later developed a second generation of TWX called "four row" that ran at 110 baud, using eight level ASCII code. TWX was offered in both "3-row" Baudot and "4-row" ASCII versions up to the late 1970s.

TWX used the public switched telephone network. In addition to having separate Area Codes (510, 610, 710, 810 and 910) for the TWX service, the TWX lines were also set up with a special Class of Service to prevent connections from POTS to TWX and vice versa.

The code/speed conversion between "3-row" Baudot and "4-row" ASCII TWX service was accomplished using a special Bell "10A/B board" via a live operator. A TWX customer would place a call to the 10A/B board operator for Baudot – ASCII calls, ASCII – Baudot calls and also TWX Conference calls. The code / speed conversion was done by a Western Electric unit that provided this capability. There were multiple code / speed conversion units at each operator position.

AT&T operated a trade magazine related to the Teletypewriter eXchange service called TWX, from 1944 to 1952, and published articles which touched upon many aspects of the technology.

Western Union purchased the TWX system from AT&T in January 1969.[8] The TWX system and the special US area codes (510, 710, 810 and 910) continued right up to 1981 when Western Union completed the conversion to the Western Union Telex II system. Any remaining "3-row" Baudot customers were converted to Western Union Telex service during the period 1979 to 1981. Bell Canada retained area code 610 until 1992; its remaining numbers were moved to non-geographic area code 600.

The modem for this service was the Bell 101 dataset, which is the direct ancestor of the Bell 103 modem that launched computer time-sharing. The 101 was revolutionary because it ran on ordinary unconditioned telephone subscriber lines, allowing the Bell System to run TWX along with POTS on a single public switched telephone network.

Telex II is the later name for the TWX teletypewriter network, which was originally founded and established by AT&T. It was later acquired from AT&T by Western Union, who renamed it Telex II. It was then re-acquired by AT&T in 1990 in the purchase of the Western Union assets that became AT&T EasyLink Services.

Western Union

In 1958, Western Union started to build a telex network in the United States.[9] This telex network started as a satellite exchange located in New York City and expanded to a nationwide network. Western Union chose Siemens & Halske AG,[10] now Siemens AG, and ITT[11] to supply the exchange equipment, provisioned the exchange trunks via the Western Union national microwave system and leased the exchange to customer site facilities from the local telephone company. Teleprinter equipment was originally provided by Siemens & Halske AG[12] and later by Teletype Corporation.[13] Initial direct international telex service was offered by Western Union, via W.U. International, in the summer of 1960 with limited service to London and Paris.[14] In 1962, the major exchanges were located in New York City (1), Chicago (2), San Francisco (3), Kansas City (4) and Atlanta (5).[15] The telex network expanded by adding the final parent exchanges cities of Los Angeles (6), Dallas (7), Philadelphia (8) and Boston (9) starting in 1966.

The telex numbering plan, usually a six-digit number in the United States, was based on the major exchange where the customer's telex machine terminated.[16] For example, all telex customers that terminated in the New York City exchange were assigned a telex number that started with a first digit "1". Further, all Chicago-based customers had telex numbers that started with a first digit of "2". This numbering plan was maintained by Western Union as the telex exchanges proliferated to smaller cities in the United States. The Western Union Telex network was built on three levels of exchanges.[17] The highest level was made up of the nine exchange cities previously mentioned. Each of these cities had the dual capability of terminating telex customer lines and setting up trunk connections to multiple distant telex exchanges. The second level of exchanges, located in large cities such as Buffalo, Cleveland, Miami, Newark, Pittsburgh and Seattle, were similar to the highest level of exchanges in capability of terminating telex customer lines and setting up trunk connections. However, these second level exchanges had a smaller customer line capacity and only had trunk circuits to regional cities. The third level of exchanges, located in small to medium-sized cities, could terminate telex customer lines and had a single trunk group running to its parent exchange.

Loop signaling was offered in two different configurations for Western Union Telex in the United States. The first option, sometimes called local or loop service, provided a 60 milliampere loop circuit from the exchange to the customer teleprinter. The second option, sometimes called long distance or polar was used when a 60 milliampere connection could not be achieved, provided a ground return polar circuit using 35 milliamperes on separate send and receive wires. By the 1970s, and under pressure from the Bell operating companies wanting to modernize their cable plant and lower the adjacent circuit noise that these telex circuits sometimes caused, Western Union migrated customers to a third option called F1F2. This F1F2 option replaced the DC voltage of the local and long distance options with modems at the exchange and subscriber ends of the telex circuit.

Western Union offered connections from Telex to the AT&T Teletypewriter eXchange (TWX) system in May 1966 via its New York Information Services Computer Center.[18] These connections were limited to those TWX machines that were equipped with automatic answerback capability per CCITT standard.

USA based Telex users could send the same message to several places around the world at the same time, like email today, using the Western Union InfoMaster Computer. This involved transmitting the message via paper tape to the InfoMaster Computer (dial code 6111) and specifying the destination addresses for the single text. In this way, a single message could be sent to multiple distant Telex and TWX machines as well as delivering the same message to non-Telex and non-TWX subscribers via Western Union Mailgram.

U.S. International record carriers

Bell's original consent agreement limited it to International Dial Telephony. The Western Union Telegraph Company had given up its international telegraphic operation in a 1939 bid to monopolize U.S. telegraphy by taking over ITT's PTT business. The result was a de-emphasis on telex in the U.S. and a "cat's cradle" of international telex and telegraphy companies. The Federal Communications Commission referred to these companies as "International Record Carriers" (IRCs).

- Western Union Telegraph Company developed a subsidiary named Western Union Cable System. This company later was renamed as Western Union International (WUI) when it was spun off by Western Union as an independent company. WUI was purchased by MCI Communications (MCI) in 1983 and operated as a subsidiary of MCI International.

- ITT's "World Communications" division (later known as ITT World Communications) was amalgamated from many smaller companies: "Federal Telegraph", "All American Cables and Radio", "Globe Wireless", and the common carrier division of Mackay Marine. ITT World Communications was purchased by Western Union in 1987.

- RCA Communications (later known as RCA Global Communications) had specialized in global radiotelegraphic connections. In 1986, it was purchased by MCI International.

- Before World War I, the Tropical Radiotelegraph Company (later known as Tropical Radio Telecommunications, or TRT) put radio telegraphs on ships for its owner, the United Fruit Company (UFC), to enable them to deliver bananas to the best-paying markets. Communications expanded to UFC's plantations, and were eventually provided to local governments. TRT eventually became the national carrier for many small Central American nations.

- The French Telegraph Cable Company (later known as FTC Communications, or just FTCC), which was owned by French investors, had always been in the United States. It laid undersea cable from the U.S. to France. It was formed by Monsieur Puyer-Quartier. International telegrams routed via FTCC were routed using the telegraphic routing ID "PQ", which are the initials of the founder of the company.

- Firestone Rubber developed its own IRC, the "Trans-Liberia Radiotelegraph Company". It operated shortwave from Akron, Ohio, USA to the rubber plantations in Liberia. TL is still based in Akron.

Bell Telex users had to select which IRC to use, and then append the necessary routing digits. The IRCs converted between TWX and Western Union Telegraph Co. standards.

Decline

Telex is still in operation, but has been mostly superseded by fax, email, and Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, although radiotelex, telex via HF radio, is still used in the maritime industry and is a required element of the Global Maritime Distress and Safety System. See Telegraphy#Worldwide status of telegram services for current information in different countries.

See also

References

- ↑ Telecommunication Journal. International Telecommunication Union. 51: 35. 1984 https://books.google.com/books?id=VjMgAQAAMAAJ. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

Fifty years of telex [...] Just over fifty years ago, in October 1933, the Deutsche Reichspost as it was then known, opened the world's first public teleprinter network.

Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ Roemisch, Rudolf (1978). "Siemens EDS System in Service in Europe and Overseas". Siemens Review. Siemens-Schuckertwerke AG. 45 (4): 176. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

The inauguration of the first telex service in the world in Germany in 1933 was soon followed by the development of similar networks in several more European countries. However, telex did not enjoy significant and worldwide growth until after 1945. Thanks to the great advantages of the new telex service, above all in overcoming time differences and language problems, telex networks were introduced in quick succession in all parts of the world.

- ↑ "RTTY Software". The DXZone.

- ↑ C. J. Colombo, “Telex in Canada”, Western Union Technical Review, January 1958: 21

- ↑ Phillip R. Easterlin, "Telex in New York", Western Union Technical Review, April 1959: 47 figure 4

- ↑ Anton A. Huurdeman (2003). The worldwide history of telecommunications. John Wiley & Sons. p. 302. ISBN 978-0-471-20505-0.

- ↑ "Typing From Afar" (PDF).

- ↑ "WU to Buy AT&T TWX". Western Union News Volume II (4). January 15, 1969.

- ↑ Phillip R. Easterlin, "Telex in New York", Western Union Technical Review, April 1959: 45

- ↑ Phillip R. Easterlin, "Telex in Private Wire Systems", Western Union Technical Review, October 1960: 131

- ↑ James S. Chin and Jan J. Gomerman, "CSR4 Exchange", Western Union Technical Review, July 1966: 142–149

- ↑ Fred W. Smith, "European Teleprinters", Western Union Technical Review, October 1960: 172–174

- ↑ Fred W. Smith, "A New Line of Light-duty Teleprinters and ASR Sets", Western Union Technical Review, January 1964: 18–31

- ↑ T.J. O’Sullivan, "TW 56 Concentrator", Western Union Technical Review, July 1963: 111–112

- ↑ Phillip R. Easterlin, "Telex in the U.S.A.", Western Union Technical Review, January 1962: 2–15

- ↑ Kenneth M. Jockers, "Planning Western Union Telex", Western Union Technical Review, July 1966: 92–95

- ↑ Kenneth M. Jockers, "Planning Western Union Telex", Western Union Technical Review, July 1966: 94 figure 2

- ↑ Sergio Wernikoff, "Information Services Computer Center", Western Union Technical Review, July 1966: 130

External links

- International Facilities of the American Carriers - an overview of the U.S. international network in May 1950