Swedish heraldry

|

Two heralds at the funeral of King Johan III, 1594 | |

| Heraldic tradition | German-Nordic |

|---|---|

| Jurisdiction | Sweden |

| Governing body | Riksarkivet |

| Chief officer | Henrik Klackenberg, Statsheraldiker |

| Former chiefs |

Clara Nevéus (1983–1999) |

| Former offices | |

| Riksheraldiker (1734–1953) |

Harald Gustaf Fleetwood (1734–1765) |

Swedish heraldry encompasses heraldic achievements in modern and historic Sweden. Swedish heraldic style is consistent with the German-Nordic heraldic tradition, noted for its multiple helmets and crests which are treated as inseparable from the shield, its repetition of colours and charges between the shield and the crest, and its scant use of heraldic furs.[1] Because the medieval history of the Nordic countries was so closely related, their heraldic individuality developed rather late.[2] Swedish and Finnish heraldry have a shared history prior to the Diet of Porvoo in 1809; these, together with Danish heraldry, were heavily influenced by German heraldry. Unlike the highly stylized and macaronic language of English blazon, Swedish heraldry is described in plain language, using (in most cases) only Swedish terminology.

The earliest known achievements of arms in Sweden are those of two brothers, Sigtrygg and Lars Bengtsson, from 1219.[3] The earliest example of Swedish civic heraldry is the city arms of Kalmar, which originated as a city seal in 1247.[4] The seal (Swedish sigill), used extensively in the Middle Ages, was instrumental in spreading heraldry to churches, local governments, and other institutions, and was the forerunner of the coat of arms in medieval Sweden.[5] Armorial seals of noblewomen appeared in the 12th century, burghers and artisans began adopting arms in the 13th century, and even some peasants took arms in the 14th century.[5]

Heraldry in Sweden today is used extensively by corporations and government offices; the rights of these private entities and of official bodies are upheld by Swedish law.[6] In order to become legally registered and protected under Swedish law, an official coat of arms must be registered with the Swedish Patent and Registration Office (PRV), and is subject to approval by the National Herald (Statsheraldiker) and the bureaucratic Heraldic Board of the National Archives of Sweden. Heraldic arms of common citizens (burgher arms), however, are less strictly controlled. These are recognised by inclusion in the annually published Scandinavian Roll of Arms.[7]

Characteristics

Swedish heraldry has a number of characteristics that distinguish the Swedish style from heraldry in other European countries. Common features of Swedish heraldry are similar to those of other Nordic countries and Germany,[2] placing it in the German-Nordic heraldic tradition, distinguished from Gallo-British heraldry and other heraldic traditions by several key elements of heraldic style.[1] One of these is the use of multiple helmets and crests, which cannot be displayed separately from the main shield. These helmets and crests are considered to be as important as the shield, each denoting a fief over which the bearer holds a right.[8] In Scandinavia (as distinct from the German custom), when an even number of helmets is displayed, they are usually turned, with their crests, to face outward; when an odd number, the center helmet is turned affronté and the rest turned outward (whereas in Germany the helmets are turned inward to face the center of the escutcheon).[8] Additionally, the crests are often repetitive of charges used on the main shield, and marks of cadency typically occur in the crest, rather than on the shield as in Gallo-British heraldry.[1] Also, the use of heraldic furs on the shield, while common in Gallo-British heraldry, is rare in German-Nordic heraldry.[1] Furs in Scandinavia are generally limited to ermine and vair, which sometimes appear in mantling, supporters, or the trimmings of crowns, but rarely on the shield.a

Consistent with German-Nordic heraldry, the most common charges in Swedish heraldry include lions and eagles. Additional animals that frequently appear in Swedish heraldry include griffins and (especially in the northern provinces) reindeer. Stars are common and are usually depicted with six points and straight sides, in contrast to the Gallo-British tradition, which typically depicts stars as either a five-pointed straight-sided star (mullet) or as a six-pointed wavy-sided star (estoile). In Swedish, these stars are usually described as "six-pointed stars" (sexuddig stjärna). In terms of blazoning, Swedish heraldry is described in plain terms using common Swedish language, rather than using specialized language such as Blazon. Canting arms occur frequently.b

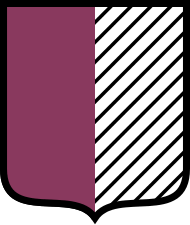

Terminology

In English, achievements of arms are usually described (blazoned) in a specialized jargon that uses derivatives of French terms. In Swedish, however, achievements of arms are described in relatively plain language, using only Swedish terms and tending to avoid specialized jargon. Examples include the use of Swedish blå and grön for blue and green, as compared to the French-derived azure and vert used in English blazon. Rather than argent, the Swedish words silver or vit (white) are used, and white, while rare, may be a different color than silver. Purpur (purple) is used in the lining of crowns and in the royal canopy of the greater national coat of arms.[9] Traditionally, purple was rarely used as a tincture on the shield, though it does appear on the shields of some (especially modern) burgher arms.[10] Ermine likewise appears in the lining of the mantling over the greater national coat of arms, but is otherwise virtually unknown in Swedish heraldry.c Vair is also rare in Scandinavian heraldry, and other furs are unknown.d

| Tinctures | Metals | Paints or Colours | Furs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escutcheons |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| English | Or | Argent | Azure | Gules | Vert | Purpure | Sable | Ermine | Vair |

| Swedish | Guld (gul) | Silver (vit) | Blå | Röd | Grön | Purpur | Svart | Hermelin | Gråverk |

| Ordinaries |  |

|

|

|

.svg.png) |

.svg.png) |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Pale | Fess | Bend | Bend sinister | Cross | Saltire | Chevron | Bordure |

| Swedish | Stolpe | Bjälke | Balk | Ginbalk | Kors | Andreaskors | Sparre | Bård |

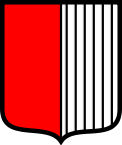

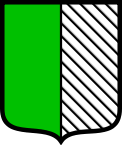

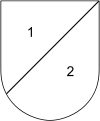

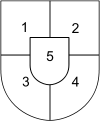

| Division of the field |  |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Party per fess | Party per pale | Party per bend sinister | Quarterly | Quarterly with an inescutcheon |

| Swedish | Delad | Kluven | Ginstyckad | Kvadrerad | Kvadrerad med hjärtsköld |

Officers of arms

In the Middle Ages, heraldic arms in Sweden were granted by the Royal Council (kungliga kansliet), but this role was turned over to the College of Antiquities (antikvitetskollegiet) in 1660.[3] Prior to 1953, the office of the National Herald (Riksheraldiker) was responsible for preparing municipal arms and the royal arms of Sweden, but today these duties are carried out by the Heraldry Board of the National Archives, including the State Herald (Statsheraldiker).[3][11] In order to register new municipal arms, a municipality must submit its proposal to both the National Archives Heraldry Board, which consults and renders an opinion, and to the PRV for registration.[11][12] Once the board has completed its consultation process and provided a warrant of arms, the arms thus warranted may then be registered by the PRV and implemented by the municipality.[11] Apart from municipal arms, heraldic arms registered by counties and by military and other government bodies are also handled by the National Archives Heraldry Board and the PRV.

The National Archives Heraldry Board, established under Swedish statute 2007:1179,[13] is the highest heraldic body in Sweden.[14] The board is chaired by the National Archivist and includes three other officials, three deputies, the State Herald (who acts as secretary), the National Archives jurist and the National Archives heraldic artist.[14] This board convenes as needed, which in recent years has been once or twice a year.[14]

The first National Herald was Conrad Ludvig Transkiöld (died 1766),[3] who served as Riksheraldiker 1734-1765.[15] Subsequent National Heralds included Daniel Tilas (1768-1772), Anders Schönberg (1773-1809), Jonas Carl Linnerhielm (1809-1829), Niklas Joakim af Wetterstedt (1829-1855), August Wilhelm Stiernstedt (1855-1880), Carl Arvid Klingspor (1880-1903), Adam Lewenhaupt (1903-1931) and Harald Fleetwood (1931-1953), and State Heralds (since the 1953 reform) have included Carl Gunnar Ulrik Scheffer (1953-1974), Lars-Olof Skoglund (1975), Jan von Konow (1975-1981), Bo Elthammar (1981-1983), and Clara Nevéus (1983-1999).[15][16] Since 1999, the State Herald of Sweden has been Henrik Klackenberg.[15][17]

The Swedish Collegium of Arms, operating under the Swedish Heraldry Society, is responsible for reviewing and registering burgher arms.[18] The Swedish Heraldry Society is a non-profit association founded in 1976,[7] and is not affiliated with the National Archives or their Heraldry Board, which registers arms of municipalities and other public entities.

National heraldry

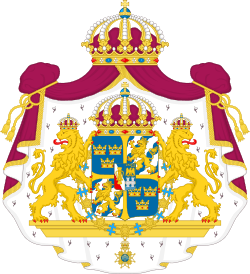

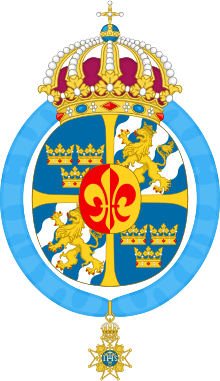

The greater national arms (stora riksvapnet) originated in 1448 and has remained unchanged in Swedish law since 1943. The first legislation of state arms in Sweden was in 1908, and prior to that the state arms were changed by royal decree.[19] It is also the personal coat of arms of the king of Sweden; as such he can decree its use as a personal coat of arms by other members of the Royal House, with the alterations and additions decided by him.[20] Since the beginning of the reign of Gustav Vasa in 1523 it has been customary in Sweden to display the arms of the ruling dynasty as an inescutcheon in the centre of the greater arms.[21]

The coat of arms of Queen Silvia of Sweden is similar to the greater arms of Sweden, but without the ermine mantling, and with the central inescutcheon exchanged for her personal arms: Per pale gules and Or, a fleur-de-lis counterchanged. The shield is encircled by an azure ribbon with dependent cross of the Order of the Seraphim.[22]

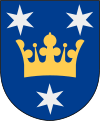

The lesser coat of arms of Sweden (lilla riksvapnet) is emblazoned: Azure, with three coronets Or, ordered two above one; Crowned with a royal crown.f This is the emblem used by the government of Sweden and its agencies; it is, for example, embroidered on all Swedish police uniforms. Any representation consisting of three crowns ordered two above one is considered to be the lesser coat of arms, and its usage is therefore restricted by Swedish Law, Act 1970:498.[6][20]

The three crowns have been a national symbol of Sweden for centuries; historians trace the use of the symbol back to the royal seal of Albrecht of Mecklenburg, and even earlier.[23] The three crowns have been recognized as the official arms of Sweden since the 14th century.[21][24] The earliest credible attribution of the three crowns is to Magnus Eriksson, who reigned over Norway and Sweden, and in 1330s, bought Scania from Denmark.[23] Written in 1378, Ernst von Kirchberg's Reimchronik depicted Magnus Eriksson with a national banner of dark blue, charged with three crowns, although this banner did not ultimately become the national flag of Sweden.[23]

The lesser coat of arms of Sweden

The lesser coat of arms of Sweden Arms of the Swedish Police Authority

Arms of the Swedish Police Authority Arms of Queen Silvia

Arms of Queen Silvia

Military heraldry

Swedish military heraldry made news headlines in Sweden and overseas in 2007, when a controversial change was made to the arms of the Nordic Battlegroup at the behest of a group of female soldiers who demanded that the lion's genitals be removed from the arms.[25][26] Vladimir Sagerlund, heraldic artist at the National Archives since 1994, was critical of the decision, saying, "once upon a time coats of arms containing lions without genitalia were given to those who betrayed the Crown."[25][27] The Times in London noted a recent trend toward heraldic "castration", pointing to the lions passant on the royal coat of arms of England, as well as the lions rampant on those of Norway, Finland, Belgium, Luxembourg and Scotland, all of which have been depicted without genitals; in conclusion, The Times wrote, "some crests are ambiguous, but the message remains clear: the lions are supposed to display courage and nothing else."[26] Officials at the National Archives treat this as a change in artistic style, rather than a heraldic change, and the lion remains in its original form on the rolls of the National Archives,g while the castrated lion appears on the unit's sleeve patches.[28] The Nordic Battle Group's coat of arms was originally designed to incorporate heraldic elements and colours from all member nations, including "a lion that did not look Finnish, Norwegian, Estonian or Swedish."[29] In an unusual move, the Armed Forces Heraldry Council authorised the Nordic Battle Group commander's use of a command sign. This consisted of a bunting divided into fields of blue, gold and blue with a Roman numeral V in the gold field, since the unit would be the fifth mobilized combat unit of the European Union.[29]

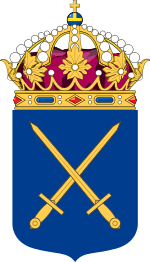

Swedish Army

The coat of arms of the Swedish Army consists of two crossed golden swords on a blue field. This motif is repeated in the flag of the Inspector General of the Army,[30] and a blue field with a single upright golden sword appears on the flag of Military Region Command infrastructure, with three gold crowns in the canton.[30]

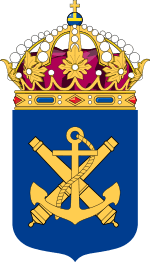

Swedish Navy

The coat of arms of the Swedish Navy, which consists of a blue field with two cannons in saltire and a cabled anchor,[31] topped with a crown, and has been used on the flags of naval commanders, including on the flag of the Inspector General of the Navy,[31] the most senior representative of the Swedish Navy’s combat forces.[32]

Regional heraldry

Each of Sweden's 21 counties (län), 25 provinces (landskap) and 290 municipalities (kommun) has its own coat of arms. The Instrument of Government (1634) introduced the modern counties of Sweden, superseding the 25 medieval provinces.h Although many of these counties have been the subject of more recent reforms, many of them occupy broadly similar regions. (See comparative maps at Counties of Sweden.) Most of the counties that have remained largely intact (Dalarna, Gotland, Skåne, Södermanland, Uppsala, Värmland, etc.) retain the respective province's coat of arms, while the redistricting of other lands has been reflected heraldically (e.g. the newly created Gävleborgs län, occupying parts of Hälsingland and Gästrikland, bears their arms quarterly). By royal decree on 18 January 1884, King Oscar II granted all provinces the rights to the rank of duchy and to display their arms with a ducal coronet.[33][34] While more exhaustive lists can be found elsewhere,i this article only discusses the arms of a few of these regions, selected for their heraldic notability. The arms of Gotland, Västerbotten, Uppland, Södermanland, Skåne and Lappland will be considered here in further detail.

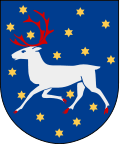

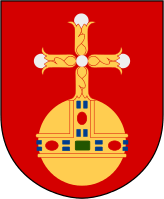

Gotland, as a free republic loosely associated with the Swedish crown, had already borne a ram with a banner (Agnus Dei) as a well-known city seal by 1280.[35] Although the island belonged to Denmark at the time, its arms were present at Gustav Vasa's funeral procession in 1560; the arms of Gotland disappeared from the Swedish rolls in 1570 but returned with the transfer of Gotland to Sweden in 1645.[35] The coat of arms is represented with a ducal coronet. Blazon: Azure, a ram statantj argent armed Or, bearing on a cross-staff of the same a banner Gules bordered and with five tails of the third.k The county was granted the same coat of arms in 1936.[36] The municipality, created in 1971, uses the same arms on a red field, influenced by the arms of Visby.[37]  Västerbotten received arms in preparation for Gustav Vasa's funeral in 1560. According to the Swedish Heraldry Society, the reindeer came to represent all lands west of the Gulf of Bothnia at that time, and Västerbotten's coat of arms received its stars in the 1590s.[38] Blazon: Azure, on a semé of stars Or, a reindeer springing argent armed gules.l The modern Västerbotten County still bears these arms in the upper portion of a shield divided per fess, with the arms of Lappland and Ångermanland in the base, to illustrate the merging of lands from these two provinces into the modern county. Blazon: Party per fess, in chief the arms of Västerbotten, and in base party per pale the arms of Lappland (dexter) and Ångermanland (sinister).m  Uppland was granted arms created for Gustav Vasa's funeral in 1560, and the royal orb symbolises spiritual and worldly power.[39] Historically, Uppland ranked as a duchy and the coat of arms was represented with a ducal coronet. Despite the fact that Uppsala län has a different name and a smaller territory, it was granted the same coat of arms in 1940, but with a royal crown in place of the ducal crown of the landskap arms. Blazon: Gules, a royal orb Or.n |

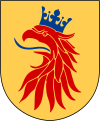

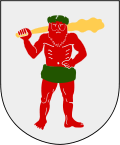

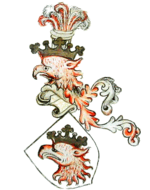

Södermanland was granted its coat of arms in 1560. According to the Swedish Heraldry Society, the arms were created for Gustav Vasa's funeral, and the choice of the griffin as charge may have been influenced by the name of Gripsholm (once home of Bo Jonsson Grip).[40] Since 1884, the coat of arms is represented with a ducal coronet. The same coat of arms was granted to Södermanland county in 1940. Blazon: Or, a griffin segreant sable, armed and langued gules, when it should be armed.o  Skåne was a Danish province without heraldic arms before its transfer to Sweden in 1658, and its arms, granted in 1660, are based on the city of Malmö's Danish era arms.[41] The Malmö arms were granted in 1437 during the Kalmar Union by Eric of Pomerania and contains a Pomeranian griffin. The Skåne coat of arms was created for the funeral of Charles X Gustav of Sweden in 1660,[41] and it is typically represented with a ducal coronet. The coat of arms for the new Skåne County, formed in 1997, was based on the arms of Kristianstad County and Malmöhus County, which in turn were based on the province arms (both former counties were divided from the old Skåne province);[42] the Skåne County arms are the province arms with different colors. When the county arms is shown crowned with a Swedish royal crown, it represents the County Administrative Board, which is the regional presence of royal government authority. Blazon: Or, a Griffin's head erased Gules, crowned and langued Azure, when it should be armed.p  Lappland itself was never considered a duchy, but was granted the right to use a ducal coronet, together with all the provinces, in 1884. The wildman first appears on a few coins minted at the time of Karl IX's coronation in 1607, and then at his funeral in 1612.[43] Blazon: Argent, a savage statant gules, crowned and clothed with birch wreaths vert, maintaining in the right hand – and depending over the shoulder – a club Or.q |

Municipal heraldry

There are 290 municipalities in Sweden, each with its own coat of arms. A local government reform in the 1960s–1970s made all cities part of a municipality. The city arms often—but not always—became the coat of arms of the new municipality. As some municipalities were created at this time by merging smaller communities, this led in some cases to arms consisting of two parts, each derived from one of the communities. Some new municipalities also lacked historical cities within, and therefore created wholly new coats of arms. Municipalities which carry the name of a city (with a few exceptions—see below) traditionally display a mural crown on top of their coat of arms.[11] While no law forbids other municipalities from using the mural crown, it is customarily reserved for those bearing former city arms.[44] Kalmar was the first to establish city arms in 1247, and Stockholm, Skara and Örebro were also among the first cities in Sweden to establish city arms.[4] As recently as 2007, Härryda Municipality was among the last municipalities in Sweden to replace its logo with a newly registered coat of arms.[45] Municipal arms may not use any colors (tinctures) other than argent, Or, gules, azure, sable and vert.[11] As in other heraldic traditions, the rule of tincture applies and it is the blazon—not the image—that is legally registered.[11]

Former city arms

The following is not an exhaustive list of the 133 historic cities in Sweden, but a brief list of cities that are notable and bear heraldic significance within the context of Swedish heraldry. Each is listed by the city name, in general chronological order with the approximate year of settlement or city charter. Note that most city arms originated in the Middle Ages as a city seal, and all were registered as municipality (kommun) arms in the 1970s.

Sigtuna (990), one of the oldest cities in Sweden, is known for its Viking Age history and rune stones. In medieval times, coins were minted at Sigtuna, and legend suggests it was the royal seat for a time, signified by the crown on its arms. The crown appeared in the city seal in 1311, and carried through to the municipal arms granted in 1971. Blazon: Azure, a crown Or between three mullets argent.[46][47]  Kalmar (1100) has the oldest known city arms in Sweden, depicting a fortified tower (borgtorn) and dating to 1247.[48] The two stars were added by the end of the 13th century, and the arms have remained virtually unchanged to date.[49] Blazon: Argent, a tower embattled gules, with door and windows Or, issuing from a wavy base azure, between two mullets of six points gules.  Arboga (13th century), settled in the 10th century, has been a city since 1480 and was the site of the first Riksdag of the Estates assembled in 1435. Arboga's city arms originated from a city seal dating from 1330.[50] The original city seal showed an eagle with three roundels placed one on each wing and the tail, and a letter "A" between two stars. The "A" was omitted and the stars moved onto the eagle's wings in 1969, and the same arms granted to the municipality in 1974.[51] Blazon: Argent, an eagle sable, beaked langued and armed gules, each wing charged with a mullet of six points Or.[50]  Malmö (1250) is the third largest city in Sweden. Malmö's arms, granted by royal decree of Eric of Pomerania in 1437, survive virtually unchanged today and, together with Halmstad, are unique in having a helmet and crest included in the achievement of arms.[11][52] Malmö's City Archives still preserve the letter written April 23, 1437 by Eric, granting his own griffin head arms to the city.r[52] Blazon: Argent, a griffin head [erased] gules crowned Or; the same upon the helmet, issuing from the crown a bundle of ostrich feathers argent and gules.  Stockholm (1250) is the largest city and present-day capital of Sweden. The original city seal depicted a city, but in 1376, the head of Saint Erik was introduced and remains in the city's seal to present day.[53] In the 1920s, the city arms were revised, based upon a church icon said to represent Saint Olaf, although the blazon clearly indicates Saint Erik as the intended subject,[54] and these arms were officially granted in 1934.[55] Blazon: Azure, a crowned head of Saint Erik [couped] Or. |

Uppsala (1286) was the seat of power in Sweden from antiquity. Since the 12th century, it has been the ecclesiastical center of Sweden, and it is the site of the oldest university in Sweden. The origin of the city arms is somewhat obscure, but the lion has been featured on Uppsala's city seal since 1737, and in the city arms which were granted in 1943.[56] Up until the 18th century (1737) there were different forms of a church in the city seal like in the arms of the city of Skara, also a seat of a bishop.[57] Blazon: Azure, a crowned lion passant gardant Or, fimbriated sable and langued and armed gules.  Landskrona (1413) was established by Eric of Pomerania while the region was part of Denmark, as an anti-Hansa city to compete with other Danish port cities under Hansa control. The city was originally symbolised by a gold "queen's crown" on a red field, in direct reference to Margrethe Valdemarsdatter, and the city received its present arms in 1880, based on a city seal from 1663 depicting a crown, a lion, a ship and a cornucopia on a quartered field.[58] Landskrona is unique among Swedish municipal arms in having its own crown and supporters as part of its own achievement.[11] Landskrona's own crown replaces the wall crown, which it has the right to use.  Gothenburg (1619), the second largest city in Sweden, was founded in 1621 by Gustav II Adolf. The city arms feature the Folkung lion of the Greater Coat of Arms of Sweden, but armed with a drawn sword and bearing the "Svea Rikes" shield (a blue shield charged with three gold crowns). The lion, king of the animals, stands for power and agility.[59] The direction of the Gothenburg lion and the crown have been especially controversial.[60] The blazon received in 1952 read: "Azure, three wavy bends sinister argent, overlaid with a lion contourné crowned with closed crown Or, with forked tail, langued and armed gules, swinging with the right forepaw a sword Or, and maintaining in the left a shield azure with three crowns Or, arranged two and one."[59]  Kiruna (1948), an iron mining town in the 20th century, became chartered as the northernmost city in Sweden in 1948 and is the seat of Kiruna Municipality, which also includes the annually rebuilt ice hotel in nearby Jukkasjärvi. The city arms of Kiruna were granted in 1949, and the municipal arms were registered in 1974. Blazon: Party per fess: Argent, the Iron alchemical symbol azure; Azure, a ptarmigan argent. Sparking local political controversy, the ptarmigan received red claws and beak in 1971.[61] |

Other municipal arms

The following examples do not represent an exhaustive list of Swedish municipal arms. See the list of municipalities of Sweden for a complete listing of these.

Oxelösund is one example of a municipality emerging from a split between two cities – in this case, Nyköping and Oxelösund, which are now in neighboring municipalities since the splitting of Nikolai rural municipality in 1950. The town of Oxelösund was established in 1900 and became a city in 1950, when it became a separate municipality from Nyköping.[62]  Stenungsund is one example of a municipality that, having no historic city arms, created wholly new arms in the 1970s. This device, displaying a hydrocarbon molecule, alludes to the area's petrochemical industry, and is also an example of distinctly modern arms. The arms, registered with the PRV in 1977, display: Argent, a hydrocarbon molecule of three pellets conjoined with six bezants gules, over a base wavy azure.[63] |

Mullsjö Municipality was newly created in 1952. The coat of arms, granted in 1977, was proposed by the municipality's recreation committee, to market the municipality as a center for winter sports.[64][65] The snow crystal is a relatively modern charge, and the modern tree-top line, called kuusikoro in Finnish, is reflective of the Finnish influence on Swedish heraldry.[66] Blazon: Azure, a snow crystal argent beneath a spruce-top chief of the same.[65]  Krokom Municipality was formed in 1974 and bears arms granted in 1977, featuring a ram (gumsen) based on a 6000-year-old rock carving at Glösabäcken.[67][68] The ram seen here was included in the seal of the legislature of Rödön from 1658.[67] While petroglyphs long predate heraldry, they rarely appear in heraldic armory. Blazon: Argent, a chevron gemel wavy inverted and diminished azure, beneath a ram in the manner of a rock carving gules.[67] |

Ecclesiastical heraldry

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coats of arms of Church of Sweden. |

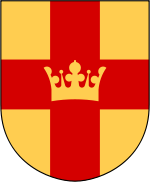

The Church of Sweden (Svenska kyrkan) is the national church (folkkyrka) and, until 2000, was the state church (statskyrka) of Sweden.[69] The arms of the church have been found displayed on a 14th-century heraldic flag discovered in Uppsala cathedral, and are blazoned: Or, upon a cross gules, a crown Or.s The crown has long been said to represent St. Erik, but in early 2005, the church issued a press release adopting "a new interpretation of the 600-year-old coat of arms which was found in Uppsala cathedral," calling it the victory crown of Christ (Kristi segerkrona).[70] The Church of Sweden also has many dioceses and parishes with their own coats of arms.

According to tradition, bishops may use the arms of their diocese marshalled with their own personal arms, with a mitre in place of the helmet and a crosier displayed behind the shield, but these are removed when the bishop retires. These arms may take the form of a shield divided per pale or quartered with the arms of the diocese in the first and third quarters and the bishop's personal arms in the second and fourth quarters.t The cross staff or "primate cross" is used only by the Archbishop of Uppsala and the Bishop of Lund, crossed with the crosier behind the shield.[71] Antje Jackelén, Bishop of Lund, uses the traditional oval shield of a woman's arms, and her arms were designed by the diocese's heraldist, Jan Raneke. Raneke also designed the arms of Jackelén's predecessor, Christina Odenberg, who was the first woman to be a bishop in the Church of Sweden.[71][72]

Personal heraldry

Noble arms

Noble arms (adliga vapen), together with royal and municipal heraldry, are protected under Swedish law since 1970.[6] In the 17th and 18th century, the nobility fought to ban burgher arms (borgerliga vapen). The result in 1767 was a compromise in that granted the nobility the exclusive right to barred or open helmets, coronets, and supporters, while "the Town law of 1730 stated that burgher arms are accepted since they are not forbidden."[4] A coronet of eleven pearls denotes a baron's arms in Sweden(the ancient nobility does also have the right to have the baronet crown by tradition), which also typically includes two barred helmets, each wearing this coronet, and a third such coronet is placed above the shield, although some baronial arms feature three helmets or only one, and not every baron uses supporters.[73] A Swedish Greve (Count) bears three barred helmets, each crowned with a coronet showing five leaves, and supporters are usually—though not always—present.[74] The arms of Swedish counts also, from the late 17th century, began using manteaux (see the Greater Coat of Arms of Sweden, pictured above) in place of the traditional mantling, although this practice has since been deprecated.[74] Untitled nobility (others granted noble status by letters patent) also bore a barred helm and a coronet showing two pearls between three leaves.[2]

The earliest known achievements of heraldry in Sweden were the noble arms of two brothers, Sigtrygg and Lars Bengtsson, of the Boberg family, dating to 1219.[3][4] Other noble arms may have been adopted into civic heraldry within their bearers' areas of influence, such as the adoption of the arms of Bo Jonsson (Grip) by Södermanland; the direct adoption of Jonsson's arms is disputed, but at the least, a certain heraldic influence is evident.u The last charter of nobility in Sweden was issued by King Oskar II to Swedish explorer Sven Hedin in 1902; this may well be the last charter ever. The 1974 constitution does not mention charters nor the nobility,[75] and the Royal orders of the State (not including, however, the Order of Carl XIII) can not be conferred to Swedes according to a special ordinance.[76] The house of nobility lost the last of its official privileges in 2003.[4]

Burgher arms

Throughout the Middle Ages, heraldry in Sweden was primarily the domain of the high nobility, but burgher arms came to Sweden in the 14th century by way of the Hansa trade.[4] This may have been especially true in Stockholm, where there was a large German population.[5] While burgher arms became popular among the merchants of the Middle Ages, by the 16th and 17th century their use was "common among the non-noble officers, judges and priests ... while the merchants tended to give up the tradition of heraldic seals and replace them with owner’s marks."[4] In contrast to noble arms, burgher arms are allowed only a shield with one tilting or closed helmet without a necklace or coronet. A wreath and crest must be placed on the helmet, and a motto or war cry can be used.[4] Unlike noble arms, few burgher arms were handed down through the generations.[5]

Burgher arms are not required to be registered with the PRV, and so they are not protected under Swedish law (1970:498). According to the Swedish Heraldry Society, the most common way of obtaining recognition of burgher arms is by inclusion in the annually published Scandinavian Roll of Arms (Skandinavisk Vapenrulla), which was first published in 1963[3] and currently includes over 400 Swedish family coats of arms, along with arms from the other Scandinavian countries.[7] Upon submission to the Swedish Heraldry Society, burgher arms are reviewed by the Swedish Collegium of Arms, whose decisions are published in the Scandinavian Roll of Arms.[18] Approximately 3000 burgher arms are known today in Sweden.[7] Swedish law protects "arms of the nobility as well as civic bodies, while burgher arms are not [protected], unless registered as a logotype."[7]

Crowns and helmets used in Swedish heraldry

Royal (Kunglig) crown

Royal (Kunglig) crown Countly (Grevlig) coronet

Countly (Grevlig) coronet Baronial (Friherrlig) coronet

Baronial (Friherrlig) coronet Noble (Adlig) coronet

Noble (Adlig) coronet

Swedish mural crown, used by cities

Swedish mural crown, used by cities Open or barred helmet, reserved for nobility

Open or barred helmet, reserved for nobility Closed or tilting helmet, used for burgher arms

Closed or tilting helmet, used for burgher arms Mitre, used by bishops in place of a helmet

Mitre, used by bishops in place of a helmet

See also

Footnotes

- ^a Volborth (1981), p. 10, states that ermine is rare in Scandinavian arms, and usually appears outside the shield (lining the royal pavilion or trimming the caps of high nobility) in continental heraldry.

- ^b Many examples of Swedish canting arms can be found here on the web.

- ^c According to this article on the Swedish Heraldry Society's web site, ermine first appeared in Sweden in the arms of Eufemiga Eriksdotter (1316–1363), and "that is the only time ermine existed in medieval Swedish heraldry."

- ^d Volborth (1981), p. 10, discusses the use of furs in Scandinavian and "Germanic countries", and notes the lack of furs in Polish heraldry. Also, according to this article on the Swedish Heraldry Society's web site, vair did not appear in Swedish heraldry until 1412–13 in the arms of Gert Comhaer of Lund, a Dutchman.

- ^e [Reserved]

- ^f Original text of Swedish statute 1982:268, 3 §, states: Lilla riksvapnet består av en med kunglig krona krönt blå sköld med tre öppna kronor av guld, ordnade två över en. Skölden får omges av Serafimerordens insignier. Såsom lilla riksvapnet skall också anses tre öppna kronor av guld, ordnade två över en, utan sköld och kunglig krona.[20]

- ^g See the 2008 version of the Nordic Battle Group arms in the rolls of the Swedish National Archives. (Direct link to image here.)

- ^h Wikisource: Swedish Instrument of Government of 1634 (in Swedish)

- ^i

Related media at Wikimedia Commons:

Related media at Wikimedia Commons:

- ^j The Swedish blazon reads "en stående vädur", which translates as "a ram statant", but the ram as conventionally depicted in the arms of Gotland and Visby, is shown as a ram trippant (otherwise as described above).

- ^k The official blazon of the arms of Gotland states: I blått fält en stående vädur av silver med beväring av guld, bärande på en korsprydd stång av guld ett rött banér med bård och fem flikar av guld.[35]

- ^l The official blazon of the arms of Västerbotten states: I med 6-uddiga stjärnor av guld bestrött blått fält en springande ren av silver med röd beväring.[38]

- ^m The official blazon of the arms of Västerbotten County states: Delad sköld, i övre fältet Västerbottens vapen, undre fältet kluvet, med Lapplands vapen till höger och Ångermanlands vapen till vänster.[77]

- ^n The official blazon of the arms of Uppland states: I rött fält ett riksäpple av guld.[39]

- ^o The official blazon of the arms of Södermanland states: I fält av guld en upprest svart grip med röd beväring, därest sådan skall komma till användning.[40]

- ^p The official blazon of the arms of Skåne states: I guldfält ett rött, avslitet griphuvud med blå krona och med blå beväring, därest dylik skall komma till användning.[41]

- ^q The official blazon of the arms of Lappland states: I fält av silver en stående röd vildman med grön björklövskrans på huvudet och kring länderna, hållande i höger hand en på axeln vilande klubba av guld.[43]

- ^r

Media related to the original grant of arms by Eric of Pomerania at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to the original grant of arms by Eric of Pomerania at Wikimedia Commons - ^s The official blazon of the arms of the Church of Sweden states: I fält av guld ett rött kors, i korsmitten belagt med en krona av guld.[78]

- ^t Examples of the former can be found in the arms of Esbjörn Hagberg, Bishop of Karlstad and Martin Lind, Bishop of Linköping, and the latter in the arms of Ragnar Persenius, Bishop of Uppsala and Antje Jackelén, Bishop of Lund.

- ^u One online article asserts that the arms of Södermanland followed on the noble arms of Bo Jonsson Grip. The seal from 1379 shown here may suggest a less direct connection, however, as the arms of Södermanland feature a full griffin and not only the head.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Warnstedt, Christopher von (October 1970). "The Heraldic Provinces of Europe", The Coat of Arms, XI (84) 128–130.

- 1 2 3 Volborth (1981), p. 129.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bäckmark, Magnus (2005-07-05). "Först som sist: När dyker olika företeelser upp inom heraldiken i Sverige?" (in Swedish). Swedish Heraldry Society. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "The Swedish Way". www.heraldik.se. Swedish Heraldry Society. 2005-06-02. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- 1 2 3 4 Volborth (1981), p. 96.

- 1 2 3 Swedish law 1970:498 protects registered arms from abuse. "Lag (1970:498) om skydd för vapen och vissa andra officiella beteckningar". Swedish Code of Statutes (in Swedish). Notisum AB. 1970-06-29. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Registration of Arms". www.heraldik.se. Swedish Heraldry Society. 2005-06-02. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- 1 2 Woodward & Burnett (1892), pp. 603–604.

- ↑ "Heraldiska färger" (in Swedish). Swedish National Archives. 2011-08-15. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ↑ "Borgerliga släktvapen". Svenska Heraldiska Föreningens vapendatabas (in Swedish). Swedish Heraldry Society. Retrieved 2013-04-29. Typing purpur into the form field Sköld 1 and pressing Sök yields a listing of ten Swedish burgher arms which use purple as a tincture on the shield. One of these listed, a coat of arms belonging to an unknown person, was found in a stained glass window in Gotland dating back to 1714.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Handledning för kommunvapnens användning" (in Swedish). Swedish National Archives. 2011-08-15. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ↑ "Kungörelse (1973:686) om registrering av svenska kommunala vapen". Swedish Code of Statutes (in Swedish). Notisum AB. 2008-08-17. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ↑ "Förordning (2007:1179) med instruktion för Riksarkivet och landsarkiven". Swedish Code of Statutes (in Swedish). Notisum AB. 2007-11-22. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- 1 2 3 "Heraldiska nämnden" (in Swedish). Swedish National Archives. 2011-08-15. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- 1 2 3 Wasling, Jesper (2007-06-28). "Riksheraldikerämbetet: En svensk institution sedan 1734" (in Swedish). Swedish Heraldry Society. Retrieved 2012-04-15.

- ↑ Nevéus, Clara (1992). Ny Svensk Vapenbok (in Swedish and English). Stockholm: Streiffert. ISBN 917886092X.

- ↑ "Heraldik" (in Swedish). Swedish National Archives. 2011-12-20. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- 1 2 "Laws of the Swedish Arms Registry" (in Swedish). Swedish Collegium of Arms. 2008-01-17. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- ↑ Granqvist, Elias (2000-07-08). "Sweden: State Arms". Flags of the World. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- 1 2 3 "Lag (1982:268) om Sveriges riksvapen". Swedish Code of Statutes (in Swedish). Notisum AB. 1982-04-29. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- 1 2 Neubecker (1979), p. 225.

- ↑ Volborth (1981), p. 94.

- 1 2 3 Engene, Jan Oskar (2007-02-10). "Three Crowns of Sweden". Flags of the World. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ↑ Volborth (1981), p. 173.

- 1 2 O'Mahony, Paul (2007-12-13). "Army castrates heraldic lion". The Local: Sweden's News in English. The Local Europe AB (Stockholm). Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- 1 2 Boyes, Roger (2007-12-15). "Military lion shorn of his equipment after women troops protest". Times Online. Times Newspapers Ltd. (London). Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ↑ Ullgren, Sven (2007-12-12). "Kvinnor fick lejonet stympat". Göteborgs Posten (in Swedish). Göteborgs-Posten (Gothenburg, Sweden). Archived from the original on December 17, 2007. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ↑ Höglund, Jan (2008-02-21). "Riksarkivet tar snoppstrid". Göteborgs Posten (in Swedish). Göteborgs-Posten (Gothenburg, Sweden). Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- 1 2 Braunstein, Christian (2007-12-10). "Weapons and flags for the NBG". Swedish Armed Forces. Retrieved 2009-03-31.

- 1 2 Heimer, Željko (2003). "Army Rank Flags (Sweden)". Flags of the World. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- ↑ "The Swedish Navy". Swedish Armed Forces website. Swedish Armed Forces. 2008-09-02. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- ↑ Bergman, Emanuel. "Dalslands vapen" (in Swedish). Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ "Vapen". Nordisk familjebok, 2nd ed. Vol. 31 (in Swedish). 1921. p. 627.

- 1 2 3 "Gotland". Heraldisk databas (in Swedish). Swedish Heraldry Society. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- ↑ "Gotlands län". Heraldisk databas (in Swedish). Swedish Heraldry Society. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- ↑ "Gotland". Heraldisk databas (in Swedish). Swedish Heraldry Society. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- 1 2 "Västerbotten". Heraldisk databas (in Swedish). Swedish Heraldry Society. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- 1 2 "Uppland". Heraldisk databas (in Swedish). Swedish Heraldry Society. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- 1 2 "Södermanland". Heraldisk databas (in Swedish). Swedish Heraldry Society. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- 1 2 3 "Skåne". Heraldisk databas (in Swedish). Swedish Heraldry Society. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- ↑ "Kristianstad län". Heraldisk databas (in Swedish). Swedish Heraldry Society. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- 1 2 "Lappland". Heraldisk databas (in Swedish). Swedish Heraldry Society. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- ↑ "Kronor" (in Swedish). Swedish National Archives. 2011-08-15. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ↑ "Härryda kommun skaffar sig kommunvapen" (in Swedish). Härryda kommun. 2007-10-12. Retrieved 2012-02-04.

- ↑ "Kommunens Vapen". Sigtuna Kommun (in Swedish). 2006-10-17. Archived from the original on January 28, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- ↑ "Sigtuna". Sveriges Kommunvapen (Swedish Civic Heraldry). 2008-07-01. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- ↑ "Kalmar". Bengans historiasidor (in Swedish). 2008-05-14. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

- ↑ "Kalmar". Sveriges Kommunvapen (Swedish Civic Heraldry). 2008-07-01. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

- 1 2 "Kommunvapen". Arboga kommun (in Swedish). 2010-12-15. Retrieved 2012-02-19.

- ↑ "Arboga". Sveriges Kommunvapen (Swedish Civic Heraldry). 2008-07-01. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

- 1 2 "Malmö stad" (in Swedish). Malmö stad. 2008-09-17. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- ↑ "S:t Eriks sigillet genom tiderna" (in Swedish). Stockholms stad. 2008-08-04. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- ↑ Rydholm, Carl-Axel (March 1998). "S:t Olof eller S:t Erik: Vem avbildas i Stockholms vapen?" (in Swedish). Retrieved 2012-02-19.

- ↑ "Stockholm". Sveriges Kommunvapen (Swedish Civic Heraldry). 2008-07-01. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

- ↑ "Uppsala". Sveriges Kommunvapen (Swedish Civic Heraldry). 2008-07-01. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

- ↑ Nevéus, Clara (1992). Ny svensk vapenbok. Stockholm: Streiffert (LCCN 92-213159), pages 152 and 126.

- ↑ Persson, Louise (2004-09-02). "Landscrone/Landskrona" (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 2008-11-19. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

- 1 2 "Stadsvapnets historia". Om Göteborg (in Swedish). Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- ↑ "Gothenburg". Sveriges Kommunvapen (Swedish Civic Heraldry). 2008-07-01. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- ↑ "Kiruna". Sveriges Kommunvapen (Swedish Civic Heraldry). 2008-07-01. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- ↑ "Oxelösunds historia". Oxelösunds Kommun (in Swedish). Retrieved 2008-07-25.

- ↑ "Kommunvapnet". Stenungsunds Kommun (in Swedish). 2008-06-10. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

- ↑ Nevéus (1992).

- 1 2 "Mullsjö". Svenska Heraldiska Föreningens vapendatabas (in Swedish). Swedish Heraldry Society. Retrieved 2009-03-29.

- ↑ Appleton, David B. (2002). New Directions in Heraldry. Retrieved 2009-03-29.

- 1 2 3 "Krokom". Svenska Heraldiska Föreningens vapendatabas (in Swedish). Swedish Heraldry Society. Retrieved 2009-03-29.

- ↑ "Turn back the clock". Krokoms Turistbyrå. Retrieved 2009-03-29.

- ↑ "Facts about the Church of Sweden". Svenska kyrkan. Retrieved 2012-02-17.

- ↑ "Kristi segerkrona i Svenska kyrkans logotype" (in Swedish). 2005-03-02. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- 1 2 Jackelén, Antje (2007-04-25). "Bishop Antje Jackelén's Coat of Arms". Svenska kyrkan. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- ↑ "News from the Church of Sweden, 3/97". Svenska kyrkan. 1998-11-17. Archived from the original on 2008-12-07. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- ↑ Volborth (1981), p. 145.

- 1 2 Volborth (1981), p. 153.

- ↑ Nobility and charters are not mentioned in any fundamental law of Sweden, the most important of them and the one regulating the field is the Instrument of Government (Regeringsformen).

- ↑ "Ordenskungörelse (1974:768)". Swedish Code of Statutes (in Swedish). Notisum AB. 1974-12-06. Retrieved 2012-02-17.

- ↑ "Västerbottens län". Heraldisk databas (in Swedish). Swedish Heraldry Society. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- ↑ "Svenska Kyrkan". Heraldisk databas (in Swedish). Swedish Heraldry Society. Retrieved 2009-07-06.

Further reading

- Neubecker, Ottfried (1979). A Guide to Heraldry. Maidenhead, England: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-046312-3.

- Nevéus, Clara (1992). Ny svensk vapenbok. Stockholm: Streiffert. ISBN 91-7886-092-X LCCN 92-213159 (in Swedish)

- Volborth, Carl-Alexander von (1981). Heraldry: Customs, Rules and Styles. Poole, England: Blandford Press. ISBN 0-7137-0940-5.

- Woodward, John and George Burnett (1892). A Treatise on Heraldry British and Foreign. Edinburgh: W. & A. K. Johnston. Vol. I Vol. II

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coats of arms of Sweden. |

- International Civic Heraldry listing

- Burgher arms in the Swedish heraldry database (in Swedish)

- The Swedish Way by the Swedish Heraldry Society

- Skandinavisk Vapenrulla (in Swedish)

- Svenskt Vapenregister (in Swedish)

- Swedish Patent and Registration Office – bilingual web site