Swarming motility

Swarming motility is a rapid (2–10 μm/s) and coordinated translocation of a bacterial population across solid or semi-solid surfaces,[1] and is an example of bacterial multicellularity and swarm behaviour. Swarming motility was first reported by Jorgen Henrichsen[2] and has been mostly studied in genus Serratia,[3][4] Salmonella,[5] Aeromonas,[6] Bacillus,[7] Yersinia,[8] Pseudomonas,[9][10][11][12][13] Proteus,[14] Vibrio[15][16] and Escherichia.[17][18]

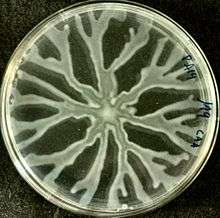

This multicellular behavior has been mostly observed in controlled laboratory conditions and relies on two critical elements: 1) the nutrient composition and 2) viscosity of culture medium (i.e. % agar).[5] One particular feature of this type of motility is the formation of dendritic fractal-like patterns formed by migrating swarms moving away from an initial location. Although the majority of species can produce tendrils when swarming, some species like Proteus mirabilis do form concentric circles motif instead of dendritic patterns.

Biosurfactant, quorum sensing and swarming

In some species, swarming motility requires the self-production of biosurfactant to occur.[5][19] Biosurfactant synthesis is usually under the control of an intercellular communication system called quorum sensing. Biosurfactant molecules are thought to act by lowering surface tension, thus permitting bacteria to move across a surface.

Cellular differentiation

Swarming bacteria undergo morphological differentiation that distinguish them from their planktonic state. Cells localized at migration front are typically hyperelongated, hyperflagellated and grouped in multicellular raft structures.[11][12][20][21]

Ecological significance

The fundamental role of swarming motility remains unknown. However, it has been observed that active swarming bacteria of Salmonella typhimurium shows an elevated resistance to certain antibiotics compared to undifferentiated cells.[22]

References

- ↑ Harshey, Rasika M. (2003-01-01). "Bacterial Motility on a Surface: Many Ways to a Common Goal". Annual Review of Microbiology. 57 (1): 249–273. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.091014. PMID 14527279.

- ↑ Henrichsen, J (1972). "Bacterial surface translocation: a survey and a classification" (PDF). Bacteriological reviews. 36 (4): 478–503. PMC 408329

. PMID 4631369.

. PMID 4631369. - ↑ Alberti, L; Harshey, RM (1990). "Differentiation of Serratia marcescens 274 into swimmer and swarmer cells". Journal of Bacteriology. 172 (8): 4322–8. PMC 213257

. PMID 2198253.

. PMID 2198253. - ↑ Eberl, L; Molin, S; Givskov, M (1999). "Surface Motility of Serratia liquefaciens MG1". Journal of Bacteriology. 181 (6): 1703–12. PMC 93566

. PMID 10074060.

. PMID 10074060. - 1 2 3 Harshey, Rasika M. (1994). "Bees aren't the only ones: swarming in Gram-negative bacteria". Molecular Microbiology. 13 (3): 389–94. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00433.x. PMID 7997156.

- ↑ Kirov, S. M.; Tassell, B. C.; Semmler, A. B. T.; O'Donovan, L. A.; Rabaan, A. A.; Shaw, J. G. (2002). "Lateral Flagella and Swarming Motility in Aeromonas Species". Journal of Bacteriology. 184 (2): 547–55. doi:10.1128/JB.184.2.547-555.2002. PMC 139559

. PMID 11751834.

. PMID 11751834. - ↑ Kearns, Daniel B.; Losick, Richard (2004). "Swarming motility in undomesticated Bacillus subtilis". Molecular Microbiology. 49 (3): 581–90. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03584.x. PMID 12864845.

- ↑ Young, GM; Smith, MJ; Minnich, SA; Miller, VL (1999). "The Yersinia enterocolitica Motility Master Regulatory Operon, flhDC, Is Required for Flagellin Production, Swimming Motility, and Swarming Motility". Journal of Bacteriology. 181 (9): 2823–33. PMC 93725

. PMID 10217774.

. PMID 10217774. - ↑ Deziel, E.; L�pine, F; Milot, S; Villemur, R (2003). "rhlA is required for the production of a novel biosurfactant promoting swarming motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: 3-(3-hydroxyalkanoyloxy)alkanoic acids (HAAs), the precursors of rhamnolipids". Microbiology. 149 (Pt 8): 2005–13. doi:10.1099/mic.0.26154-0. PMID 12904540. replacement character in

|last2=at position 2 (help) - ↑ Tremblay, Julien; Richardson, Anne-Pascale; L�pine, François; D�ziel, Eric (2007). "Self-produced extracellular stimuli modulate the Pseudomonas aeruginosa swarming motility behaviour". Environmental Microbiology. 9 (10): 2622–30. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01396.x. PMID 17803784. replacement character in

|last3=at position 2 (help); replacement character in|last4=at position 2 (help) - 1 2 K�hler, T; Curty, LK; Barja, F; Van Delden, C; Pech�re, JC (2000). "Swarming of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Is Dependent on Cell-to-Cell Signaling and Requires Flagella and Pili". Journal of Bacteriology. 182 (21): 5990–6. doi:10.1128/JB.182.21.5990-5996.2000. PMC 94731

. PMID 11029417. replacement character in

. PMID 11029417. replacement character in |last1=at position 2 (help); replacement character in|last5=at position 5 (help) - 1 2 Rashid, MH; Kornberg, A (2000). "Inorganic polyphosphate is needed for swimming, swarming, and twitching motilities of Pseudomonas aeruginosa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (9): 4885–90. doi:10.1073/pnas.060030097. PMC 18327

. PMID 10758151.

. PMID 10758151. - ↑ Caiazza, N. C.; Shanks, R. M. Q.; O'Toole, G. A. (2005). "Rhamnolipids Modulate Swarming Motility Patterns of Pseudomonas aeruginosa". Journal of Bacteriology. 187 (21): 7351–61. doi:10.1128/JB.187.21.7351-7361.2005. PMC 1273001

. PMID 16237018.

. PMID 16237018. - ↑ Rather, Philip N. (2005). "Swarmer cell differentiation in Proteus mirabilis". Environmental Microbiology. 7 (8): 1065–73. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00806.x. PMID 16011745.

- ↑ McCarter, L.; Silverman, M. (1990). "Surface-induced swarmer cell differentiation of Vibrio parahaemoiyticus". Molecular Microbiology. 4 (7): 1057–62. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00678.x. PMID 2233248.

- ↑ McCarter, Linda L. (2004). "Dual Flagellar Systems Enable Motility under Different Circumstances". Journal of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology. 7 (1–2): 18–29. doi:10.1159/000077866. PMID 15170400.

- ↑ Harshey, RM; Matsuyama, T (1994). "Dimorphic transition in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: surface-induced differentiation into hyperflagellate swarmer cells". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (18): 8631–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.18.8631. PMC 44660

. PMID 8078935.

. PMID 8078935. - ↑ Burkart, M; Toguchi, A; Harshey, RM (1998). "The chemotaxis system, but not chemotaxis, is essential for swarming motility in Escherichia coli". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (5): 2568–73. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.5.2568. PMC 19416

. PMID 9482927.

. PMID 9482927. - ↑ Daniels, Ruth; Vanderleyden, Jos; Michiels, Jan (2004). "Quorum sensing and swarming migration in bacteria". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 28 (3): 261–89. doi:10.1016/j.femsre.2003.09.004. PMID 15449604.

- ↑ Julkowska, D.; Obuchowski, M; Holland, IB; S�ror, SJ (2004). "Branched swarming patterns on a synthetic medium formed by wild-type Bacillus subtilis strain 3610: detection of different cellular morphologies and constellations of cells as the complex architecture develops". Microbiology. 150 (Pt 6): 1839–49. doi:10.1099/mic.0.27061-0. PMID 15184570. replacement character in

|last4=at position 2 (help) - ↑ Hamze, K.; Autret, S.; Hinc, K.; Laalami, S.; Julkowska, D.; Briandet, R.; Renault, M.; Absalon, C.; Holland, I. B. (2011-01-01). "Single-cell analysis in situ in a Bacillus subtilis swarming community identifies distinct spatially separated subpopulations differentially expressing hag (flagellin), including specialized swarmers". Microbiology. 157 (9): 2456–2469. doi:10.1099/mic.0.047159-0.

- ↑ Kim, W.; Killam, T.; Sood, V.; Surette, M. G. (2003). "Swarm-Cell Differentiation in Salmonellaenterica Serovar Typhimurium Results in Elevated Resistance to Multiple Antibiotics". Journal of Bacteriology. 185 (10): 3111–7. doi:10.1128/JB.185.10.3111-3117.2003. PMC 154059

. PMID 12730171.

. PMID 12730171.