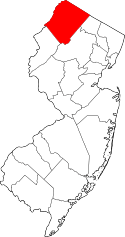

Sussex County, New Jersey

| Sussex County, New Jersey | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Looking east from the ridge of Kittatinny Mountain in Walpack Township | |||

| |||

Location in the U.S. state of New Jersey | |||

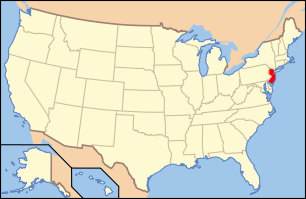

New Jersey's location in the U.S. | |||

| Founded | June 8, 1753[1] | ||

| Named for | Sussex, England | ||

| Seat | Newton[2] | ||

| Largest city | Vernon Township (population and area) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 535.74 sq mi (1,388 km2) | ||

| • Land | 519.01 sq mi (1,344 km2) | ||

| • Water | 16.73 sq mi (43 km2), 3.12% | ||

| Population | |||

| • (2010) |

149,265[3] 143,673 (2015 est.)[4] | ||

| • Density | 276.8/sq mi (106.9/km²) | ||

| Congressional districts | 5th, 11th | ||

| Website |

www | ||

Sussex County is the northernmost county in the State of New Jersey. Its county seat is Newton.[2][5] It is part of the New York City Metropolitan Area. The county had a Census-estimated population of 143,673 in 2015, a 3.7% decrease from the 149,265 enumerated in the 2010 United States Census,[4] in turn an increase of 5,099 (3.5%) over the 144,166 persons enumerated in the 2000 Census, retaining its position as the 17th-most populous county among the state's 21 counties.[6] Based on 2010 Census data, Vernon Township was the county's largest in both population and area, with a population of 23,943 and covering an area of 70.59 square miles (182.8 km2).[7] As of 2010 The Bureau of Economic Analysis ranked the county as having the 131st-highest per capita income ($49,207) of the 3,113 counties in the United States (and the ninth-highest in New Jersey).[8]

The county was established in 1753 and named after historic County Sussex, England.[9][10]

Because of its topography, Sussex County has remained a relatively rural and forested area. The county is part of the Skylands Region, a term promoted by the New Jersey Commerce, Economic Growth, & Tourism Commission to encourage tourism. In the western half of the county, several state and federal parks have kept the large tracts of land undeveloped and in their natural states. The eastern half of the county has had more suburban development because of its proximity to more populated areas and commercial development zones.

Until the mid-20th century, most of Sussex County's economy was based on agriculture (chiefly dairy farming) and the mining industry. With the decline of these industries in the 1960s, Sussex County was transformed into a bedroom community that absorbed population shifts from New Jersey's urban areas. Recent studies estimate that 60 percent of Sussex County residents work outside of the county, many seeking or maintaining employment in New York City or New Jersey's more suburban and urban areas.

History

The area of Sussex County and its surrounding region was occupied for approximately 8,000-13,000 years by succeeding cultures of indigenous peoples.[11] At the time of European encounter, the Munsee Indians inhabited the region. The Munsee were a loosely organized division of the Lenape (or Lenni Lenape), a Native American people also called "Delaware Indians" after their historic territory along the Delaware River. The Lenape inhabited the mid-Atlantic coastal areas and inland along the Hudson and Delaware rivers.[12] The Munsee spoke a very distinct dialect of the Lenape and inhabited a region bounded by the Hudson River, the head waters of the Delaware River and the Susquehanna River, and south to the Lehigh River and Conewago Creek.[13][14] As a result of disruption following the French and Indian War (1756–1763) the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) and later Indian removals from the eastern United States, the main Lenape groups now live in Ontario in Canada, and in Wisconsin and Oklahoma in the United States.[15][16]

As early as 1690, Dutch and French Huguenot colonists from towns along the Hudson River Valley in New York began permanently settling in the Upper Delaware Valley (known as the "Minisink"). The route these Dutch settlers had taken was the path of an old Indian trail and became the route of the Old Mine Road and stretches of present-date U.S. Route 209.[17] These Dutch settlers penetrated the Minisink Valley and settled as far south as the Delaware Water Gap, by 1731 this valley had been incorporated as Walpack Precinct. Throughout the 18th century, immigrants from the Rheinland Palatinate in Germany and Switzerland fled religious wars and poverty to arrive in Philadelphia and New York City. Several German families began leaving Philadelphia to settle along river valleys in Northwestern New Jersey and Pennsylvania's Lehigh Valley in the 1720s, spreading north into Sussex County in the 1740s and 1750s as additional German emigrants arrived.[18][19] Also during this time, Scottish settlers from Elizabethtown and Perth Amboy, and English settlers from these cities, Long Island, Connecticut and Massachusetts, came to New Jersey and moved up the tributaries of the Passaic and Raritan rivers, settling in the eastern sections of present-day Sussex and Warren counties.[19]

By the 1750s, residents of this area began to petition colonial authorities for a new county to be formed; they complained of the inconvenience of long travel to conduct business with the government and the courts. By this time, four large townships had been created in this sparsely populated Northwestern region: Walpack Township (before 1731), Greenwich Township (before 1738), Hardwick Township (1750) and Newtown Township (1751). On June 8, 1753, Sussex County was created from these four municipalities, which had been part of Morris County when Morris stretched over all of northwestern New Jersey.[1] Sussex County at this time encompassed present-day Sussex and Warren Counties and its boundaries were drawn by the New York-New Jersey border to the north, the Delaware River to the west, and the Musconetcong River to the south and east.[20] After several decades of debate over where to hold the sessions of the county's courts, the state legislature eventually voted to divide Sussex County in two, using a line drawn from the juncture of the Flat Brook and Delaware River in a southeasterly direction to the Musconetcong River running through the Yellow Frame Presbyterian Church in present-day Fredon Township (then part of Hardwick).[21] On November 20, 1824, Warren County was created from the southern territory of the Sussex County.[21]

Throughout the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, Sussex County's economy was largely centered around agriculture and the mining of iron and zinc ores. Early settlers established farms whose operations were chiefly focused towards subsistence agriculture. Because of geological constraints, Sussex County's agricultural production was centered around dairy farming. Several farms had orchards—typically apples and peaches—and surplus fruit and grains were often distilled or brewed into alcoholic beverages (hard ciders, applejack and fruit brandies). This was the economic model until the mid-19th century when advances in food preservation and the introduction of railroads (e.g. the Sussex Railroad) into the area allowed Sussex County to transport farm products throughout the region. Railroads also promoted the building of factories as companies relocated to the area at the end of the 19th century—including that of the H.W. Merriam Shoe Company (1873) in Newton.[22]

The Highlands Region of Northwestern New Jersey has proven to possess rich deposits of iron ore. In the mid 18th century, several entrepreneurial colonists began mining iron in area around Andover, Hamburg, and Franklin present-day Sussex County and establishing forges and furnaces to create pig iron and bar iron. During the American Revolution, the Quartermaster Department of the Continental Army complained to Congress of difficulties in acquiring iron to support the war effort and the Congress ordered two colonels, Benjamin Flower and Thomas Maybury to take possession of the iron works at Andover in order to equip General Washington's army. During the middle of the 19th century, under the management of Cooper and Hewitt, the Andover mine produced 50,000 tons of iron ore each year. The firm manufactured railroad rails and the country's first structural steel, which and led to the building of railroads and commercial development in the county. Iron from the Andover mines was fashioned into cable wire for the bridge built at Niagara Falls and for the beams used to rebuild Princeton University's Nassau Hall in Princeton, New Jersey after a fire undermined the structure in 1855. During the American Civil War, Andover iron found its way into rifle barrels and cannonballs just as it had during the Revolution years before.

As deposits were depleted, the iron mining industry began to diminish by the mid-19th century. During the late 19th century, prolific American inventor Thomas Edison began to explore the commercial opportunities of processing poor-quality low-grade iron ore to combat the growing scarcity of iron deposits in the United States.[23] He began to purchase mining companies in Sussex County in the 1880s and consolidating their assets.[24] He developed a process of crushing and milling iron-bearing minerals and separating iron ore from the material through large electromagnets, and built one of the world's largest ore-crushing mills near Ogdensburg. Completed in 1889, the factory contained three giant electromagnets and was intended to process up to 1200 tons of iron ore every day. However, technical difficulties repeatedly thwarted production.[25][26] However, in the 1890s, richer soft-grade iron ore deposits located in Minnesota's Iron Range rendered Edison's Ogdensburg operation unprofitable and he closed the works in 1900.[25][26] Edison adapted the process and machinery for the cement industry and invested in producing Portland Cement in other locations.[27][28]

In the early 19th century, Samuel Fowler (1779–1844) settled in Franklin Furnace (now Franklin) to open up a medical practice, but is largely known for his interest in mineralogy which led to his developing commercial uses for zinc and for discovery of several rare minerals (chiefly various ores of zinc).[29][30] Many of these zinc minerals are known for fluorescing in vivid colors when exposed to ultraviolet light.[30][31] Because of both the rich deposits and many of these minerals are not found anywhere else on earth, Franklin is known as the "Fluorescent Mineral Capitol of the World."[31][32][33] Fowler, who later briefly served in elected political office, operated the local iron works and bought several abandoned zinc and iron mines in the area.[29][30] Shortly after his death, two companies were created to exploit the iron and zinc deposits in this region; they acquired the rights to Fowler's holdings in Franklin and nearby Sterling Hill. These companies later merged to form the New Jersey Zinc Corporation (today known as Horsehead Industries).[30] At this time, Russian, Chilean, British, Irish, Hungarian and Polish immigrants came to Franklin to work in the mines, and the population of Franklin swelled from 500 (in 1897) to over 3,000 (in 1913).[34] Declining deposits in the Franklin area, the expense of pumping groundwater from mine shafts, tax disputes and misdirected investments by the company led to the abandonment of the mines.[30][35] Today, both the Franklin and Sterling Hill mines are operated as museums.[35]

Beginning in the 1950s and 1960s, construction or improvements of Interstate 80, Route 181 and Route 23 triggered rapid growth to Sussex County. Since 1950, the population has increased from 34,423 people to 130,943 people in 1990.[36] This has caused Sussex County to begin developing into a light suburban atmosphere, instead of the sparsely populated rural region it once was, especially in the eastern half of the county.

Geology

Around 450 million years ago the Martinsburg Shale was uplifted when a chain of volcanic islands collided with proto North America. These islands slid over the North American plate, and deposited rock on top of the plate, forming the Highlands and Kittatinny Valley. At that time the western part of Sussex County was under a shallow inland sea. Fossils of sea shells and fish can be found west of the Kittatinny ridge. Then approximately 400 million years ago, a small, narrow continent collided with North America. Pressure from the collision, created heat in the bed rock which folded and faulted the Silurian Shawangunk Conglomerate that was under the shallow sea. The pressure created intense heat, melted the quartzite, and allowed it to bend, creating an uplift. as cooling occurred this cemented the quartz pebbles and conglomerate together. This is how the Kittatinny Ridge was created. The strike from this continent was from the south east, this is why the Kittatinny ridge is on a northeast-southwest axis. The Wisconsin glacier which covered the entire county from 23,000B.C to 13,000 B.C. created many lakes and streams. The glacier covered Kittatinny mountain.

As climate warmed around 13,000 B.C. the area was first a tundra with lichens and mosses. After a few thousand years coniferous forests began to grow. As climate grew warmer around 8000 B.C., deciduous forests began to grow with nut trees such as oak, and maple. Around 3000 B.C. other nut bearing trees began to grow such as hickory, butternut, walnut and beech. This allowed the Paleo Indian populations to increase. The county is drained by the Paulinskill River, the Flatbrook, which drain into the Delaware River, the Wallkill River which flows north to the Hudson River. There are many smaller creeks that drain into these water sheds.

High Point, located at the northernmost tip of New Jersey in Montague Township, is the highest natural elevation in the state at 1,803 feet (549.5 m) above sea level.[37][38][39] Nearby, Sunrise Mountain in Stokes State Forest has an elevation of 1,653 feet (504 m). Many mountains in the Highlands region range between 1000 and 1500 feet (375–450 m).[40]:p.3 Officially, the county's lowest elevation is approximately 300 feet (90 m) above sea level along the Delaware River near Flatbrookville.[41] However, local authorities claim that the mine adit descending 2,675 feet (815 m) at the Sterling Hill Mine in Ogdensburg is unofficially the lowest elevation in New Jersey.[38]

Population

According to the 2010 Census, the county had a total area of 535.74 square miles (1,387.6 km2), including 519.01 square miles (1,344.2 km2) of land (96.9%) and 16.73 square miles (43.3 km2) of water (3.1%).[7][42] It is the fourth-largest of the state's 21 counties in terms of area.[43]

Physiographic provinces

Sussex County is located within two of New Jersey's physiographic provinces: (1) The Ridge and Valley Appalachians, and (2) the New York-New Jersey Highlands regions.[44]

The features of the Ridge and Valley province were created approximately 400 million years ago during the Ordovician period and Appalachian orogeny— by a continent striking North America the creating Kittatinny Mountain, Blue Mountain, and the Appalachian Mountains.[45][46] This physiographic province occupies approximately two-thirds of the county's area (the county's western and central sections) dominated by Kittatinny Mountain and the Kittatinny Valley. This province's contour is characterized by long, even ridges with long, continuous valleys in between that generally run parallel from southwest to northeast. This region is largely formed by sedimentary rock.[44][47]

The New York-New Jersey Highlands, or Highlands region, located in the county's eastern section is older. An extension of the Reading Prong formation stretching from Pennsylvania to Connecticut, the Highlands were created from geological forces created from when a small continent went over the North American plate. This rock created the highlands of Sussex County. Precambrian igneous and metamorphic rock approximately 500 million years ago.[44][48] The watersheds within the Highlands provide fresh water resources for millions of residents in New Jersey and the New York City Metropolitan Area.[49] Because of this, the region was protected by the New Jersey Legislature and Governor Jim McGreevey under the Highlands Water Protection and Planning Act enacted in 2004.[50] This act sought to protect these water resources from development by promoting open space and farmland preservation, creating new recreational parks, and consolidating the regulatory authority over land use planning in a regional planning commission known as the Highlands Council.[51][52]

Mountains and valleys

The Delaware River forms the western and northwestern boundary of Sussex County. This region is known as the Upper Delaware Valley and historically as the Minisink or Minisink Valley. Elevations in the regions along the river range from 300 to 500 feet.[40]:p.3

Kittatinny Mountain is the dominant geological feature in the western section of the county. It is part of the Appalachian Mountains, and part of a ridge that continues as the Blue Mountain in Eastern Pennsylvania, and as Shawangunk Ridge in New York to the north. It begins in New Jersey as the eastern half of the Delaware Water Gap, and runs northeast to southwest along the Delaware River. Elevations range from 1,200 feet (370 m) to 1,800 feet (550 m) and attains a maximum elevation of 1,803 feet (550 m) at High Point, in Montague Township.[40]:p.3 Between Kittatinny Mountain and the Delaware River is the Wallpack Ridge, a smaller, narrow ridge spanning 25 miles (40 km) in length from the Walpack Bend near Flatbrookville north to Port Jervis, New York. Wallpack Ridge encloses the watershed of the Flat Brook and its two main tributaries Little Flat Brook and Big Flat Brook, and ranges in elevation from 500 feet (150 m) to 900 feet (270 m) and reaching its highest elevation at 928 feet (283 m).[40]:p.3 [53]

The Kittatinny Valley lies to the east of Kittatinny Mountain and ends with the Highlands in the east. It is largely a region of rolling hills and flat valley floors. Elevations in this valley range from 400 to 1,000 feet.[40]:p.3 It is part of the Great Appalachian Valley running from eastern Canada to northern Alabama. This valley is shared by three major watersheds—the Wallkill River, with its tributaries Pochuck Creek and Papakating Creek flowing north; and the Paulins Kill watershed and Pequest River watershed flowing southwest. This valley floor consists of shale and slate (part of the Ordovician Martinsburg Formation) and of limestone (part of the Jacksonburg Formation). Several parties have argued about the possibility of natural gas extraction in the region's Martinsburg and Utica shale formations, similar to the Marcellus Shale formations to the West in Pennsylvania and New York.[54] Of special interest is Rutan Hill, a 440-million-year-old patch of igneous rock known as nepheline syenite. This site, north of Beemerville in Wantage Township, was once an ancient volcano—the only extant dormant volcano sites in the state.[55]

Dividing the Kittatinny Valley (and the Ridge and Valley Province) from the Highlands region is a narrow fault of Hardyston Quartzite. Many of the mountains in the Highlands are not part of a solid, linear ridge and tend to randomly rise from the surrounding land as the result of folds, faults and intrusions. Elevations in the Highlands region range from 1,000 to 1,500 feet.[40]:p.3 The more prominent mountains in this area are Hamburg Mountain (elevation: 1,495 feet (456 m)), Wawayanda Mountain (elevation 1,448 feet (441 m)), Sparta Mountain (elevation: 1,232 feet (376 m)) and Pochuck Mountain (elevation: 1,194 feet (364 m)) which form a ridge along the county's eastern flank.

Rivers and watersheds

Sussex County's rivers and watersheds flow in three directions; north to the Hudson River, west and south to the Delaware River, and east toward Newark Bay.

- Wallkill River is an 88.3-mile-long (142.1 km) river starting at its source at Lake Mohawk in Sparta Township drains north into Rondout Creek, a tributary of the Hudson River.[56] The Wallkill River drains a 785 square miles (2,030 km2) watershed.[57]

- Pochuck Creek is an 8.1-mile-long (13.0 km) creek flowing north into the Wallkill River.[56]

- Papakating Creek is a 20.1-mile-long (32.3 km) creek in the north central region of the county beginning in Frankford Township also drains into the Wallkill.[56]

- Clove Creek is a 12.0-mile-long (19.3 km) creek that flows into the Papakating Creek near Lewisburg in Wantage Township.[56]

- The Flat Brook is a 11.6-mile-long (18.7 km) creek flowing through Walpack and Sandyston Townships, joins the Delaware River at the Walpack Bend. It has two main tributaries: the Little Flat Brook whose length is 12.6-mile-long (20.3 km) and Big Flat Brook whose length is 16.5-mile-long (26.6 km).[56]

- The Paulins Kill (or, incorrectly, Paulinskill) is a 41.6-mile-long (66.9 km) river with its two branches: the West Branch is fed by Bear Swamp, Lake Owassa, Culver's Lake, and the Dry Brook in Frankford Township, the Main or East Branch starting at Newton combining near Augusta to flow southwest through Hampton, Stillwater, Hardwick, Blairstown, and Knowlton townships to join the Delaware River near the Delaware Water Gap.[56] The Paulins Kill drains a 176.85 square miles (458.0 km2) watershed.[58]

- The Pequest River is a 35.7-mile-long (57.5 km) beginning near Newton and Springdale and flowing through in Andover and Green Township, then through Warren County before joining the Delaware near Belvidere.[56]

- The Musconetcong River is a 45.7-mile-long (73.5 km) river beginning at Lake Hopatcong, forms the eastern border between Warren County and Morris and Hunterdon Counties.[56] Its main tributaries are Lubbers Run and Punkhorn Creek.

- Small sections of eastern Sussex County drain into the watersheds of the Pequannock River, Passaic River, and Rockaway River which end in Newark Bay.

Historically, these rivers and streams were used to power various types of mills (i.e. grist mills, fulling mills, etc.), transport goods to market, and later to generate electric power (after 1880). Today, these rivers are chiefly used in local recreational activities—including canoeing and fishing. The Fish Culture Unit of the New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife stocks these waterways each year with various species of trout.[59] Some of these rivers—especially the Flat Brook, Paulins Kill and Pequest—have become well known as trout streams and for their suitability for fly-fishing.[60] The Flat Brook and its tributary the Big Flat Brook are regarded as the state's premiere trout stream.[61]

Soils

According to the Natural Resource Conservation Service, Sussex County soils are derived from parent materials that are largely till and glaciofluvial deposits, alluvium, and organic matter deposits. Till is the rock of soil material transported or deposited by glacial ice. In this case, the most recent glaciation (i.e. the last ice age), the Wisconsinian continental glacier, deposited a till plain composed of ground and recessional moraines. This glaciation reached its maximum extent roughly 22,000 years ago (20,000 B.C.E.). Glaciofluvial deposits (or "outwash") are rock and soil materials that melting glaciers deposit as the glacier recedes. Alluvium is materials that are deposited by floodwaters from engorged bodies of water—chiefly streams and rivers. Organic deposits are largely the result of decomposing plant material.[40]:p.213–216[62]

Geography

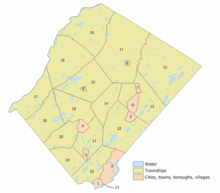

Municipalities

The following are Sussex County's 24 incorporated municipalities (with census-designated places (CDPs) listed within their parent municipalities and 2010 Census populations shown for some places):[7][63][64]

|

|

Adjacent counties

With its location at the top of New Jersey, Sussex County is bordered by counties in New Jersey, and neighboring New York and Pennsylvania. Because it is shaped roughly like a diamond or rhombus with its point matching the cardinal points of the compass, its boundary lines are roughly oriented along the ordinal or intercardinal directions.

The following counties are adjacent and contiguous to Sussex County (in order starting with the northernmost and rotating clockwise):

- Orange County, New York – to the northeast (along the boundary line between New York and New Jersey).

- Passaic County, New Jersey – to the east

- Morris County, New Jersey – to the east and south

- Warren County, New Jersey – to the southwest

- Monroe County, Pennsylvania – to the west (for a few hundred yards at the county's westernmost tip, Walpack Bend in the Delaware River)

- Pike County, Pennsylvania – to the northwest (along the Delaware River)

State and federal protected areas

A large percentage of Sussex County is undeveloped because it has been reserved as one of 11 federal or state parks or as part of several wildlife management areas.

- Under the National Park Service

- Appalachian National Scenic Trail (shared by 14 states)

- Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area (shared with Pennsylvania)

- Middle Delaware National Scenic River (shared with Pennsylvania)

- Under the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- Wallkill River National Wildlife Refuge (shared with New York)

- Under the New Jersey Division of Parks and Forestry

- Allamuchy Mountain State Park

- High Point State Park

- Hopatcong State Park

- Kittatinny Valley State Park

- Stokes State Forest

- Swartswood State Park

- Wawayanda State Park

- New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife[65]

|

|

Climate and weather

Because of its location in the higher elevations of northwestern New Jersey's Appalachian mountains, Sussex County has a cooler humid continental climate or microthermal climate (Köppen Dfb) which indicates patterns of significant precipitation in all seasons and at least four months where the average temperature rises above 10 °C (50 °F)[66][67] This differs from the rest of the state which is generally a humid mesothermal climate, in which temperatures range between -3 °C (27 °F) and 18 °C (64 °F) during the year's coldest month.[67][68] Sussex County is part of USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 6.[69][70]

During winter and early spring, New Jersey in some years is subject to "nor'easters"—significant storm systems that have proven capable of causing blizzards or flooding throughout the northeastern United States. Hurricanes and tropical storms, tornadoes, and earthquakes are relatively rare. The Kittatinny Valley to the north of Newton, part of the Great Appalachian Valley, experiences a snowbelt phenomenon and has been categorized as a microclimate region known as the "Sussex County Snow Belt." This region receives approximately forty to fifty inches of snow per year and generally more snowfall that the rest of Northern New Jersey and the Northern Climate Zone.[71] This phenomenon is attributed to the orographic lift of the Kittatinny Ridge which impacts local weather patterns by increasing humidity and precipitation, providing the ski resorts of Vernon Valley in the northeastern part of this region with increased snowfall.[72]

In recent years, average temperatures in the county seat of Newton have ranged from a low of 17 °F (−8 °C) in January to a high of 84 °F (29 °C) in July. Average monthly precipitation ranged from 2.86 inches (73 mm) in February to 4.76 inches (121 mm) in June.[73]

According to the USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service soil survey, the area receives sunshine approximately 62% of the time in summer and 48% in winter. Prevailing winds are typically from the southwest for most of year; but in late winter and early spring come from the northwest. The lowest recorded temperature was −26 °F on January 21, 1994. The highest recorded temperature was 104 °F (40 °C) on September 3, 1953. The heaviest one-day snowfall was 24 inches recorded on January 8, 1996 (combined with the next day, total snowfall was 40 inches). The heaviest one-day rainfall–6.70 inches— was recorded on August 19, 1955.[40]

| Climate data for Sussex, New Jersey (1981–2010 normals) — NOAA-SUSSEX 2 NW (288644) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 71 (22) |

73 (23) |

90 (32) |

95 (35) |

97 (36) |

98 (37) |

106 (41) |

102 (39) |

102 (39) |

92 (33) |

84 (29) |

75 (24) |

106 (41) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 34.1 (1.2) |

37.9 (3.3) |

46.8 (8.2) |

58.9 (14.9) |

69.8 (21) |

77.8 (25.4) |

82.3 (27.9) |

80.8 (27.1) |

73.1 (22.8) |

62.2 (16.8) |

50.9 (10.5) |

38.7 (3.7) |

59.4 (15.2) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 15.8 (−9) |

17.9 (−7.8) |

25.7 (−3.5) |

36.1 (2.3) |

45.4 (7.4) |

55.1 (12.8) |

60.0 (15.6) |

58.0 (14.4) |

50.1 (10.1) |

38.4 (3.6) |

31.0 (−0.6) |

21.6 (−5.8) |

37.9 (3.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −29 (−34) |

−23 (−31) |

−10 (−23) |

9 (−13) |

24 (−4) |

33 (1) |

40 (4) |

34 (1) |

27 (−3) |

13 (−11) |

6 (−14) |

−13 (−25) |

−29 (−34) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.19 (81) |

2.83 (71.9) |

3.69 (93.7) |

4.27 (108.5) |

4.10 (104.1) |

4.41 (112) |

4.02 (102.1) |

4.18 (106.2) |

4.23 (107.4) |

4.52 (114.8) |

3.47 (88.1) |

3.74 (95) |

46.65 (1,184.8) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 13.8 (35.1) |

9.4 (23.9) |

6.5 (16.5) |

2.0 (5.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1.3 (3.3) |

9.2 (23.4) |

42.2 (107.3) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.6 | 8.6 | 11.1 | 12.4 | 12.6 | 11.0 | 10.9 | 10.7 | 9.1 | 10.1 | 9.9 | 10.7 | 127.7 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 5.4 | 3.7 | 2.6 | .5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .1 | .6 | 3.2 | 16.1 |

| Source: NOAA (extremes 1893–present)[74] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Population statistics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 19,500 | — | |

| 1800 | 22,534 | 15.6% | |

| 1810 | 25,549 | 13.4% | |

| 1820 | 32,752 | 28.2% | |

| 1830 | 20,346 | * | −37.9% |

| 1840 | 21,770 | 7.0% | |

| 1850 | 22,989 | 5.6% | |

| 1860 | 23,846 | 3.7% | |

| 1870 | 23,168 | −2.8% | |

| 1880 | 23,539 | 1.6% | |

| 1890 | 22,259 | −5.4% | |

| 1900 | 24,134 | 8.4% | |

| 1910 | 26,781 | 11.0% | |

| 1920 | 24,905 | −7.0% | |

| 1930 | 27,830 | 11.7% | |

| 1940 | 29,632 | 6.5% | |

| 1950 | 34,423 | 16.2% | |

| 1960 | 49,255 | 43.1% | |

| 1970 | 77,528 | 57.4% | |

| 1980 | 116,119 | 49.8% | |

| 1990 | 130,943 | 12.8% | |

| 2000 | 144,166 | 10.1% | |

| 2010 | 149,265 | 3.5% | |

| Est. 2015 | 143,673 | [4][75] | −3.7% |

| Historical sources: 1790–1990[36] 1970–2010[7] 2000[76] 2010[3] 2000–2010[77] * = Lost territory in previous decade.[1] | |||

Census 2010

The 2010 United States Census counted 149,265 people, 54,752 households, and 40,626 families residing in the county. The population density was 287.6 per square mile (111.0/km2). The county contained 62,057 housing units at an average density of 119.6 per square mile (46.2/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 93.46% (139,504) White, 1.79% (2,677) Black or African American, 0.16% (234) Native American, 1.77% (2,642) Asian, 0.02% (36) Pacific Islander, 1.19% (1,783) from other races, and 1.60% (2,389) from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 6.44% (9,617) of the population.[3]

Out of a total of 54,752 households, 33.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 61% were married couples living together, 9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 25.8% were non-families. 21% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.69 and the average family size was 3.14.[3]

In the county, 24% of the population were under the age of 18, 7.6% from 18 to 24, 23.9% from 25 to 44, 32.6% from 45 to 64, and 12% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 41.8 years. For every 100 females the census counted 98.5 males, but for 100 females at least 18 years old, it was 96.9 males.[3]

Census 2000

As of the 2000 United States Census[78] there were 144,166 people, 50,831 households, and 38,784 families residing in the county. The population density was 277 people per square mile (107/km²). There were 56,528 housing units at an average density of 108 per square mile (42/km²). The racial makeup of the county was 95.70% White, 1.0% Black or African American, 0.11% Native American, 1.20% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.74% from other races, and 1.14% from two or more races. 3.30% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.[76][79] Among those residents listing their ancestry, 24.5% were of Italian, 22.9% German, 22.2% Irish, 10.7% English, 8.1% Polish and 5.2% Dutch ancestry according to Census 2000.[79][80]

In 2000 there were 50,831 households out of which 39.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 65.0% were married couples living together, 8.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 23.7% were non-families. 18.9% of all households were made up of individuals and 6.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.80 and the average family size was 3.24.[76]

In the county the age distribution of the population shows 27.9% under the age of 18, 6.2% from 18 to 24, 31.5% from 25 to 44, 25.3% from 45 to 64, and 9.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females there were 98.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 95.6 males.[76]

Affluence and poverty

Sussex County is considered an affluent area as many of its residents are college-educated, employed in professional or service jobs, and earn above the state's average per capita income and household income statistics. As of 2010, the Bureau of Economic Analysis ranked the county as having the 131st-highest per capita income of all 3,113 counties in the United States (and the ninth-highest in New Jersey).[8] Average per capita income was $49,207 and was 23.2% above the national average.[8]

As of the 2000 Census, the median household income was $65,266 and the median family income was $73,335. Males had a median income of $44,544 compared with $32,487 for females. The per capita income for the county was $26,992. About 6.30% of families and 8.40% of the population were below the poverty line, including 10.50% of those under age 18 and 8.00% of those age 65 or over.[79][81]

As of 2010, there were a total of 54,881 households enumerated in the 2010 census, with a reported median household income of $84,115, or mean household income of $96,527. Males had a median income of $50,395 versus $33,750 for females. The per capita income for the county was $26,992. About 2.8% of families and 4.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 4.1% of those under age 18 and 5.4% of those age 65 or over.

| Household income | Number of households | Percentage of households |

|---|---|---|

| Less than $10,000 | 1,754 | 3.2% |

| $10,000 to $14,999 | 1,136 | 2.1% |

| $15,000 to $24,999 | 2,771 | 5.0% |

| $25,000 to $34,999 | 4,026 | 7.3% |

| $35,000 to $49,999 | 5,872 | 10.7% |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 9,365 | 17.1% |

| $75,000 to $99,999 | 8,209 | 15.0% |

| $100,000 to $149,999 | 12,927 | 23.6% |

| $150,000 to $199,999 | 4,714 | 8.6% |

| $200,000 or more | 4,107 | 7.5% |

As of the 2006–2010 American Community Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, 3.6% of county residents were living below the poverty line which the government defined as an annual household income under $22,350 for a family of four.[82] However, recent surveys indicate that in the county's town centers, Sussex Borough (15.1%), Newton (12.8%) and Andover Borough (12.7%), poverty levels reach double-digits.[82] Of these poverty-level residents, an estimated 44% are employed, many of them underemployed despite working multiple jobs.[82]

Employment and labor force

As of the 2010 Census, the county's unemployment rate was 11.0%. The Census Bureau reported a population of 118,420 persons (above age 16) available for the labor force of which 82,449 (69.6%) were actively employed in civilian labor, and 35,971 (30.4%) were not in the labor force.

| Category | Persons employed | Percentage of labor force |

|---|---|---|

| Management, business, science, and arts occupations | 29,443 | 40.1% |

| Service occupations | 11,689 | 15.9% |

| Sales and office occupations | 18,712 | 25.5% |

| Natural resources, construction and maintenance occupations | 6,715 | 9.2% |

| Production, transportation, and material moving occupations | 6,784 | 9.2% |

| TOTAL | 73,343 |

| Category | Persons employed | Percentage of labor force |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting, and mining | 674 | 0.9% |

| Construction | 5,495 | 7.5% |

| Manufacturing | 7,922 | 10.8% |

| Wholesale trade | 2,303 | 3.1% |

| Retail trade | 8,536 | 11.6% |

| Transportation and warehousing, and utilities | 3,791 | 5.2% |

| Information | 2,074 | 2.8% |

| Finance and insurance, and real estate and rental and leasing | 6,642 | 9.1% |

| Professional, scientific, and management, and administrative and waste management services | 7,963 | 10.9% |

| Educational services, and health care and social assistance | 16,268 | 22.2% |

| Arts, entertainment, and recreation, and accommodation and food services | 6,629 | 9.0% |

| Other services, except public administration | 2,033 | 2.8% |

| Public administration | 3,013 | 4.1% |

| TOTAL | 73,343 |

Economy

Early industry and commerce chiefly centered on agriculture, milling, and iron mining. As iron deposits were exhausted, mining shifted toward zinc deposits near Franklin and Ogdensburg during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The local economy expanded due to the introduction of railroads and shortly after the Civil War, the town centers hosted factories. However, the factories, railroads and mining declined by the late 1960s. Today, Sussex County features a mix of rural farmland, forests and suburban development. Because agriculture (chiefly dairy farming) has decreased and that the county hosts little industry, Sussex County is considered a "bedroom community" as most residents commute to neighboring counties (Bergen, Essex and Morris counties) or to New York City for work.

Agricultural production

Although Sussex County's dairy farming industry has declined significantly in the last 50 years it is still the majority of agricultural production in the region.[83] Trucking has replaced railroads in the transportation of milk products to regional production facilities and markets. Rising taxes, regulation and decreasing profitability in dairy farming have forced farmers to adapt by growing other products or converting their farms to other uses.[83] Many farmers have sold their properties to real estate developers who have built residential housing. Many Sussex County farms are nursery farms producing ornamental trees, plants and flowers used in horticulture, floristry or landscaping. Christmas trees and nursery and greenhouse plants contribute to 51% of the county's annual crop revenues but account for 30% of crop production.[83]

Despite the decline of dairy farming, it is still the largest contributor to the county's annual agricultural revenues. According to the Sussex County Comprehensive Farmland Preservation Plan (2008):

dairy production has steadily trended downward since 1971, when the county produced 138 million pounds of milk. By 2005 this quantity had fallen to 38.4 million pounds. The decrease is further reflected in the number of dairy farms and milk cows in 1982 as compared to 2002. In 1982 there were 137 dairy farms; by 2002 the number had decreased to only 30. In 1982 there were 6,406 milk cows; in 2002 the quantity had fallen to 1,943.[84]

According to county agricultural statistics, 17.3% of all crop sales ($1.4 million in 2002) were in hay. Nearly 80% of tilled farmland, or 21,195 acres (8,577 ha), on 43% of the farms in the county is dedicated to hay production. Much of hay is grown for feed on livestock farms — especially dairy farms — and never makes it to market and is therefore not included in federal agricultural census data.[84] In 2002, 4,059 acres (1,643 ha) were dedicated to corn cultivation, the majority of it used for feed on the same farms.[84]

According to the 2007 Census of Agriculture compiled by the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Agricultural Statistics Service, Sussex County has 1,060 farms totaling 65,242 acres (26,403 ha; 101.941 sq mi) out of New Jersey's total 10,327 farms managing 773,450 acres (313,000 ha; 1,208.52 sq mi). This is up from 1,029 farms in the 2002 Census. However, acreage dedicated to agriculture declined by 13.6% from 75,496 acres (30,552 ha; 117.963 sq mi) in 2002.[85] Note though that 102,547 acres—roughly 30% of the county's land area—are under farmland assessment for the purpose of calculating property tax levies.[86] This decrease is total acreage is due, in large part, to "suburban sprawl" as farmers capitalized by converting to commercial and residential development. The average size of a farm in 2007 was 62 acres (25 ha) acres, down from 73 acres (30 ha).[85] The 2007 acreage dedicated to agriculture is roughly 19.6% of the county's land area. The county-wide total agricultural product sales in 2007 was $21,242,000, up from $14,756,000 in 2002.[85] Total county market value of land and buildings in 2007 was $888,955,000, an increase from $520,997,000 in 2002. The average market value per farm was $838,636 (2007), up from $505,823 (2002). This results in a per acre price of $13,625 (2007), up from $7,136 (2002).[85]

With the repeal of several prohibition-era alcohol laws in 1981, 43 wineries have become licensed and are operating in the state. New Jersey wines have grown in stature due to increased marketing and quality, recent successes and awards in competitions, and appreciation by critics. Sussex County is home to three established and operating wineries and three more are in development.[87]

Industry and manufacturing

Sussex County's industrial and manufacturing base is no longer towards heavy industry and mining. Today, companies like Thorlabs, are located here.

Taxes

Because of its lower population, large amount of land area preserved by state and federal parks and open space preservation programs, and conservative politics, Sussex County has lower spending on education (through regional school districts) and government services and thus has lower taxes than its neighboring counties. Most municipalities do not have police departments or paid firemen—instead relying on the rural service of the New Jersey State Police and volunteer fire departments. In several municipalities, taxes on an acre of land, depending on the condition and size of the house, could be as low as $1,500 a year. Typical property taxes in the county are in the $4,000–$8,000 a year range.

Government and politics

Board of Chosen Freeholders

Sussex County is governed by a five-member Board of Chosen Freeholders who are elected in partisan elections on an at-large basis to serve three-year terms of office as part of the November general election. This board serves both as a legislative body and as an administrative body with broad powers over the county's budget, government services, and infrastructure. Seats on the five-member board are elected on a staggered basis over a three-year cycle, with two seats available in the first year, two seats the following, and then one seat. All terms of office begin on January 1 and end on December 31. At an annual reorganization meeting held in the beginning of January, the board selects a Freeholder Director and Deputy Director from among its members, with day-to-day supervision of the operation of the county delegated to a County Administrator.[88]

As of 2014, Sussex County's Freeholders are:[88][89][90][91][92]

- Freeholder Director Richard Vohden (R, Green Township, term ends December 31, 2016)[93]

- Deputy Director Dennis J. Mudrick (R, Sparta Township, 2015)[94]

- Phillip R. Crabb (R, Franklin, 2014)[95]

- George Graham (R, Stanhope, 2016)[96] Graham was chosen in April 2013 to fill the seat vacated by Parker Space, who had been chosen to fill a vacancy in the New Jersey General Assembly.[97]

- Gail Phoebus (R, Andover Township, 2015)[98]

The freeholders appoint a County Administrator to oversee the day-to-day management of the county by both "implementing the policy directives set forth by the Board of Chosen Freeholders" and "directing, managing, or guiding the County's administrative departments, divisions and agencies." The Administrator is John Eskilson.[99] Many services overseen by the county government overlap with those provided at the municipal level. The County government oversees and administers the following areas of responsibility:

|

|

Before 1911, two freeholders from each township were elected annually to serve on the board. However, as this became unwieldy in the late 19th Century during the era of Boroughitis and the creation of hundreds of municipalities, the State Legislature chose to reorganize the size of county freeholder boards to an odd number between three and nine members. The size of the board was a reflection of the county's population. As Sussex County was rural and among the least populated counties in the state, for the next 80 years, Sussex County's Board of Chosen Freeholders consisted of three elected members. The board increased from three to five members in 1992.

Constitutional officers

Pursuant to Article VII Section II of the New Jersey State Constitution, each county in New Jersey is required to have three elected administrative officials known as "constitutional officers." These officers are the County Clerk (elected for a five-year term), the County Surrogate (elected for a five-year term) and the County Sheriff (elected for a three-year term).[100]

The County Clerk is responsible for certifying notaries; processing and recording deeds, mortgages, and real estate documents; business trade names, processing petitions from candidate for elective office, drawing up ballots, overseeing elections and counting ballots, and many other tasks.[101] The County Clerk is Jeffrey M. Parrott (R, 2016).[102]

The County Sheriff is responsible for law enforcement, protection of the courts, administering the county jail, and the delivery and service of court documents. The current County Sheriff is Michael F. Strada (R, 2016).[103]

The County Surrogate is both a constitutional officer and judge with jurisdiction over estate and probate matters (wills, guardianships, trusteeships), and in processing adoptions.[104] The County Surrogate is Gary R. Chiusano (R).[105]

Sussex County is a part of Vicinage 10 of the New Jersey Superior Court (along with Morris County), which is seated at the Morris County Courthouse in Morristown; the Assignment Judge for Vicinage 15 is the Honorable Stuart M. Minkowitz.[106][107][108] Cases venued in Sussex County are heard at the Sussex County Judicial Center in Newton.[108]

State and federal representation

Sussex County is part of two congressional districts:[109][110]

- The 5th congressional district, which consists of roughly four-fifths of Sussex County (its northern and western area), all of Warren County, and parts of Passaic and Bergen counties. New Jersey's Fifth Congressional District is represented by Scott Garrett (R, Wantage Township).[111]

- The 11th congressional district contains the southeastern corner of Sussex County (Byram Township, Hopatcong Borough, Ogdensburg Borough, Stanhope Borough, and Sparta Township) and parts of Essex, Morris and Passaic counties. New Jersey's Eleventh Congressional District is represented by Rodney Frelinghuysen (R, Harding Township).[112]

New Jersey is represented in the United States Senate by Cory Booker (D, Newark, term ends 2021)[113] and Bob Menendez (D, Paramus, 2019).[114][115]

All of Sussex County is in the 24th Legislative District, along with portions of Morris and Warren counties.[116][117] For the 2016–2017 session (Senate, General Assembly), the 24th Legislative District of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Steve Oroho (R, Franklin) and in the General Assembly by Parker Space (R, Wantage Township) and Gail Phoebus (R, Andover Township).[118]

Politics

Sussex County is a predominantly Republican area, as among registered voters, affiliations with the Republican Party outpace those of the Democratic Party by a ratio of about five to two.[119] All five members of the county board of Chosen Freeholders, all three county-wide constitutional officers, and all except a few of the 108 municipal offices among the county's 24 municipalities are held by Republicans.

In the 2004 U.S. Presidential election, George W. Bush carried the county by a 29.6% margin over John Kerry, the largest margin for Bush in any county in New Jersey, with Kerry carrying the state by 6.7% over Bush.[120] In 2008, John McCain carried Sussex County by a 20.6% margin over Barack Obama, McCain's best showing in New Jersey, with Obama winning statewide by 15.5% over McCain.[121] Sussex County is the home county of Scott Garrett, who is by far the most conservative congressman from New Jersey. He represents almost all of Sussex County along with Warren County, northern Passaic County, and northern Bergen County. The southeast corner of Sussex County is represented by Rodney Frelinghuysen.

As of March 23, 2011, there were a total of 98,158 registered voters in Sussex, of which 16,150 (16.5% vs. 16.5% countywide) were registered as Democrats, 38,583 (39.3% vs. 39.3%) were registered as Republicans and 43,311 (44.1% vs. 44.1%) were registered as Unaffiliated. There were 114 voters registered to other parties.[119] Among the county's 2010 Census population, 65.8% were registered to vote, including 86.5% of those ages 18 and over.[119][122]

In the 2012 presidential election, Republican Mitt Romney received 40,625 votes here (59.4%), ahead of Democrat Barack Obama with 26,104 votes (38.2%) and other candidates with 1,465 votes (2.1%), among the 68,404 ballots cast by the county's 100,152 registered voters, for a turnout of 68.3%.[123] In the 2008 presidential election, Republican John McCain received 44,184 votes here (59.2%), ahead of Democrat Barack Obama with 28,840 votes (38.7%) and other candidates with 1,130 votes (1.5%), among the 74,593 ballots cast by the county's 96,967 registered voters, for a turnout of 76.9%.[124] In the 2004 presidential election, Republican George W. Bush received 44,506 votes here (63.9%), ahead of Democrat John Kerry with 23,990 votes (34.4%) and other candidates with 900 votes (1.3%), among the 69,649 ballots cast by the county's 89,679 registered voters, for a turnout of 77.7%.[125]

In the 2009 gubernatorial election, Republican Chris Christie received 31,749 votes here (63.3%), ahead of Democrat Jon Corzine with 12,870 votes (25.7%), Independent Chris Daggett with 4,563 votes (9.1%) and other candidates with 663 votes (1.3%), among the 50,137 ballots cast by the county's 95,941 registered voters, yielding a 52.3% turnout.[126]

Law enforcement

Police and public safety

Municipalities that do not have their own police departments have services provided by the New Jersey State Police. One of the primary responsibilities of the New Jersey State Police is to provide police services to these rural towns, for which the municipality is assessed an annual fee paid to the state government[127] The New Jersey State Police are located on Route 206 in Augusta. Less than half of the county's municipalities have a local police department. Police Departments are located in the municipalities of Vernon, Hardyston, Sparta, Byram, Hopatcong, Stanhope, Andover, Newton, Ogdensburg, Franklin, and Hamburg. The other 13 municipalities are rural and rely on State Police coverage. Stillwater disbanded its police department in 2010. The New Jersey State Park Police has jurisdiction throughout the state, but patrol primarily in Stokes State Forest and other local state parks.

Crime

Crime is relatively low in Sussex County.

In the 2012 New Jersey Uniform Crime Report, Sussex County reported the following arrests:[128]

- Murder: 1

- Rape: 1

- Robbery: 16

- Aggravated Assault: 50

- Burglary: 115

- Larceny – Theft: 348

- Motor Vehicle Theft: 5

- Total: 536

The above arrest data includes both minor and adult arrests.

Media and communications

Newspapers

Sussex County has one daily newspaper, the New Jersey Herald, which is published six days each week (Sunday through Friday). Established in 1829 by Grant Fitch, the Herald is one of the oldest continuing newspapers in the state with distribution throughout Sussex County and into neighboring Morris and Warren counties in New Jersey, Orange County, New York and Pike County, Pennsylvania. Its headquarters, and production facilities are located in Newton, New Jersey.[129] Its printing facilities were located in Newton, as well, but in 2012 the newspaper's printing was outsourced to North Jersey Media Group, located in Rockaway, New Jersey.[130]

It was for most of its existence published once per week. It's Sunday edition, the New Jersey Sunday Herald, was first published on June 11, 1962, and for the next few years it was published twice weekly. In 1969, after a sale to American Newspapers, Inc., a daily edition was planned which began publication on March 16, 1970. American Newspapers, Inc., sold the New Jersey Herald to Quincy Newspapers (its current owner) in March 1980. Today, its content includes coverage of local news and sporting events (chiefly those in Sussex County) and printing selected articles from the Associated Press covering state, national and international events.[131]

Television

Sussex County is served by Service Electric Cable Television (SECTV) through its affiliate Service Electric Cable Company in Sparta, New Jersey. Service Electric also offers broadband Internet and telephone services through two partner companies, PenTeleData and Ironton Telephone.[132] Service Electric has offered channels for local access programming (channel 10) and for "community bulletin boards". It offers two free Public Service Announcements or event advertisements for free to non-profit organizations in Sussex and Warren Counties.[133]

WMBC-TV an independent television station owned by Mountain Broadcasting Corporation, is licensed to operate in Newton. It is recognized for providing Korean language programming in the New York metropolitan area but also offers English-language programs. Its studios are located in West Caldwell, New Jersey and its transmitter near Lake Hopatcong. Before 2009, it operated an analog transmission on virtual channel 63 (UHF-63) but has converted to broadcasting its signal on digital channel 18.

The New Jersey Public Broadcasting Authority maintains the license to operate a low-power translator (W36AZ) in Sussex Borough to broadcast the state's public television station, NJTV.[134] This station, which used to be the New Jersey Network (NJN), is operated by WNET.org, the parent company of New York City's flagship public television stations, WNET and WLIW, through a subsidiary nonprofit organization, Public Media NJ.

Radio

Sussex County is served largely by radio stations in the New York City metropolitan area. Stations from Lehigh Valley in Pennsylvania; Hudson Valley in New York; can also be heard. iHeartMedia owns a cluster of three stations in the county, including: 102.3 FM WSUS in Franklin (Format: Adult contemporary), 103.7 FM WNNJ in Newton (Format: Classic rock), and 106.3 FM WHCY in Franklin (Format: Contemporary Hits Radio/Top 40). Centro Biblico of NJ also owns a Spanish language Christian station, 1360 AM WTOC in Newton.

Stations nearby include 91.9 FM WXPJ broadcast from Centenary College in Hackettstown (Warren County) with a public radio and progressive music format and 1110 AM WTBQ in Warwick, New York with a NewsTalk and Sports format.

New Jersey Public Radio (NJN), affiliated with National Public Radio and American Public Media, operates two stations in the region: 88.5 FM WNJP in Sussex, and 89.3 FM WNJY in Netcong.

Transportation

Roads and highways

Sussex County is served by a number of roads connecting it to the rest of the state and to both Pennsylvania and New York. According to the county government, "a vast majority of residents who use single occupant vehicles to travel outside the county for employment. Thus, the demand for public transportation in the county is minimal."[135] Interstate 80 passes through the extreme southern tip of Sussex County solely in Byram.[136] Interstate 84 passes just yards north of Sussex County, but never enters New Jersey. New Jersey's Route 15, Route 23, Route 94, Route 181, Route 183, and Route 284 pass through the County, as does U.S. Route 206.[137][138]

As of 2010, the county had a total of 1,313.67 miles (2,114.15 km) of roadways, of which 888.54 miles (1,429.97 km) were maintained by the local municipality, 313.29 miles (504.19 km) by Sussex County and 111.35 miles (179.20 km) by the New Jersey Department of Transportation and 0.49 miles (0.79 km) by the Delaware River Joint Toll Bridge Commission.[139]

Sussex County has two toll-bridge crossings over the Delaware River. Operated by the Delaware River Joint Toll Bridge Commission, the Milford-Montague Toll Bridge (also known as the US 206 Toll Bridge) carries U.S. Route 206 over the Delaware connecting Montague Township and Milford, Pennsylvania. The current bridge was opened in 1954, replacing a series of bridges located here beginning in 1826.[140]:p.73–85 Route 206 merges with U.S. Route 209 a mile south of the village center. Tolls are collected only from motorists traveling westbound, into Pennsylvania. The Dingman's Ferry Bridge is the last privately owned toll bridge on the Delaware River and one of the last few in the United States.[140]:p.93–102[141] It is owned and operated by the Dingmans Choice and Delaware Bridge Company which has operated bridges here since 1836.[140]:p.93–102[141] The bridge connects the village of Dingmans in Delaware Township in Pike County, Pennsylvania and State Route 2019 with County Route 560 and the Old Mine Road in Sandyston Township, New Jersey.

Commuter rail service

As of 2012, Sussex County's sole operating railroad line is dedicated to freight service in Sparta, Vernon and Hardyston townships. It is operated by the New York, Susquehanna & Western railroad and CSX Transportation.[142] Commuter rail service has not been offered in the county since the 1960s.[143] However, commuter rail service is available from nearby stations along New Jersey Transit's Morris and Essex Lines in Hackettstown, Mount Olive, Netcong, Lake Hopatcong, Mount Arlington and Dover, which are easily accessible to Sussex County residents by driving or through bus services contracted by New Jersey Transit.[144] This line was part of the former Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad system.[145] Service is available directly to Hoboken Terminal or via the Kearny Connection (opened in 1996) to Secaucus Junction and Pennsylvania Station in Midtown Manhattan.[144] Passengers can transfer at Newark Broad Street Station or Summit to reach either New York or Hoboken.[144]

New Jersey Transit is planning to re-open commuter service through the Lackawanna Cut-Off route which passes through Andover and Green Townships in the southern part of the county. Service from a planned station in Andover into New York City and Hoboken is scheduled to begin in 2016.[146] The portion of the Cut-Off route west of Andover heading toward Scranton, Pennsylvania has not been funded or scheduled.[146]

Bus service

NJ Transit in partnership with the county government offers bus service in Sussex County, limited to weekday service on the "Skylands Connect" route.[147] The county government's Office of Transit also operates a ParaTransit bus service on weekdays to local senior citizens, veterans, people with disabilities, and the general public. It offers service within the county for local errands (nutrition, medical appointments, shopping, hairdresser appointments, banking, community services, education/training, and employment) and outside the county for non-emergency medical appointments (dialysis, therapy, radiation treatment, mental health, specialized hospitals, and Veterans facilities).[148]

Lakeland Bus Lines, a privately operated commuter bus company based in Dover, in Morris County offers service under contract with New Jersey Transit between Newton and Sparta to New York City's Midtown Port Authority Bus Terminal.[135][149][150]

Airports

There are four general aviation public-use airports in Sussex County that cater to recreational pilots. They include:

- Aeroflex-Andover Airport (FAA LID 12N) also in Andover Township. This airport is located in Kittatinny Valley State Park and is owned and operated by the New Jersey Forest Fire Service.[151] It has one 1,981 feet (604 m) runway designated 3/21 and is located at and elevation of 583 feet (178 m) above mean sea level.[152]

- Newton Airport (FAA LID 3N5) located in Andover Township and is privately owned. It has one 2,546 feet (776 m) runway with a 6/24 designation and is located at an elevation of 620 feet (190 m) above mean sea level.[153]

- Sussex Airport (FAA LID FWN) located in Wantage Township and is privately owned. It has a 3,499 feet (1,066 m) runway with a 3/21 designation and is located at an elevation of 421 feet (128 m) above mean sea level.[154]

- Trinca Airport (FAA LID 13N) located in and owned by Green Township, which has a 1,924-foot (586 m) grass runway with a 6/24 designation and located at an elevation of 600 feet (180 m) above mean sea level.[155]

Education

Primary and secondary schools

Before 1942, Sussex County had over 100 school districts. Most of these districts were in rural townships that each had several districts—each district operating a one-room schoolhouse that served their small neighborhoods. During the forty-year tenure (1903–1942) of County School Superintendent Ralph Decker, the local government began to consolidate these small districts into larger municipality-wide or regional school districts.[157]

The public school system in Sussex County offers a "thorough and efficient" education for children between the ages of five and eighteen years (grades K–12), as required by state constitution,[158] through nine local and regional public high school districts, and twenty public primary or elementary school districts. Because of its distance from other county high schools and the higher costs of busing students one of those locations, Montague Township (the northernmost municipality in the state) sends most of its middle school (grades 7–8) and high school students (grades 9–12) to Port Jervis, New York for schooling. However, in 2013, Montague began exploring alternatives that would involve keeping their students in-state by sending them to High Point Regional High School in neighboring Wantage Township. Several of the county's schools are highly ranked by both state and federal education departments; some of which have achieved the U.S. Department of Education Blue Ribbon School Award.[159] The county's Board of Chosen Freeholders oversees the Sussex County Technical School (formerly the Sussex County Vocational-Technical School), a county-wide technical high school in Sparta Township.[160]

Pope John XXIII Regional High School in Sparta operates under the auspices of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Paterson, which also operates the three K-8 schools in the county: Immaculate Conception in Franklin, St. Joseph in Newton and Rev. George A. Brown in Sparta.[161] There are several other private schools in the county.

Sussex County's 10 high schools compete in interscholastic sports and other athletic activities sanctioned by the New Jersey State Interscholastic Athletic Association (NJSIAA). In 2009, the NJSIAA reorganized statewide athletic leagues into regional conferences.[162] Prior to this reorganization, these schools competed under the auspices of the Sussex County Interscholastic League (SCIL), a now-defunct county-wide conference affiliated with NJSIAA.[163] SCIL and other Morris and Warren County high schools compete under the NJSIAA's Northwest Jersey Athletic Conference.[164]

Higher education

Sussex County Community College (commonly referred to as SCCC) is an accredited, co-educational, two-year, public, community college located on a 167-acre (68 ha) campus in Newton. The SCCC campus was the site of Don Bosco College, a Roman Catholic seminary operated by the Salesian Order from 1928 until it was closed in the early 1980s and its campus sold to the Sussex County government on 22 June 1989 for US$4,209,800.[165][166]

SCCC was authorized as a "college commission" in 1981 and began operations the following year. It became fully accredited in 1993 by the Commission on Higher Education of the Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools.[167][168] SCCC offers 40 associate degree and 16 post-secondary professional and health science certificate programs available both at traditional classes at its campus, through hybrid and online classes, and through distance learning.[168][169][170] Many students who attend SCCC transfer to pursue the completion of their undergraduate college education at a four-year college or university.[169][171] The college also offers programs for advanced high school students, community education courses, and programs in cooperation with the New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development.[172] As of 2012, SCCC reported an enrollment of 3,403 students of which 56% attend full-time and 44% attended part-time.[167]

Before it closed in 1995, Upsala College, a Lutheran-affiliated college in East Orange, New Jersey, operated a 245-acre (99 ha) satellite campus in Wantage Township which it named the "Wirth Campus." In 1978, the land known as "Twin Ponds Farm" had been donated by Wallace "Wally" Wirths (1921–2002), a former Westinghouse Corporation executive, author, local newspaper columnist and radio commentator.[173][174][175] The school had considered moving to Sussex County as East Orange's crime problem and social conditions deteriorated in the 1970s. However, declining enrollment and financial difficulties forced the school to close.[176][177] The Wirths family bought back the farm for $75,000.[175][178]

Tourism and recreation

Sussex County is part of the Skylands Region, a term promoted by the New Jersey Commerce, Economic Growth, & Tourism Commission to encourage regional tourism. New Jersey ranks fifth in the nation in revenues generated from tourism.

Agritourism

Local dairy farmers have had to adapt to a declining milk and dairy industry and reacclimate to changing economic conditions by seeking new sources of revenue.[83] Combining their agricultural production while promoting tourism, "Agritourism" has created opportunities for farmers. Many Sussex County farms offer corn field mazes, "u-pick" or "pick your own" fruits and vegetables—especially for apples, strawberries, pumpkins and Christmas trees during their respective harvest seasons.[179]

New Jersey's wine industry has benefited from the recent easing of state alcohol licensing laws and from new promotional and marketing programs offered by the state's Department of Agriculture. Of the state's 46 licensed wineries, Sussex County is home to three: Cava Winery & Vineyard in Hamburg, Ventimiglia Vineyard in Wantage Township, and Westfall Winery in Montague Township.[87]

Sussex County Fairgrounds

The Sussex County Farm and Horse Show which has operated since 1918 is now the New Jersey State Fair.

Outdoor recreation

There are nine wildlife management areas located in Sussex County for hunting, fishing, trapping, hiking, snowshoeing and cross country skiing, covering more than 15,000 acres (6,100 ha). There are also several state forests and state parks.

Skiing and winter sports

In the 1960s, Vernon Township became a location for skiing and winter sports.

Sports franchises

Sussex County has one large venue for professional sports, Skylands Stadium, a 4,200-seat baseball stadium located in the Augusta section of Frankford Township near the intersection of U.S. Route 206, New Jersey Route 15, and County Route 565.[180] While it was home to two minor league baseball teams and one semi-professional football team, and briefly hosted other franchises, it has been vacant for several years. In 2013, Skylands Park was acquired by investor Mark Roscioli Jr., of 17 Mile, LLC for $950,000.[181] Roscioli who admits a lack of experience in sports management, was negotiating to bring a baseball team to the park but sold the facility to an unknown buyer.[180][182]

With the rise of professional Minor League Baseball in the 1990s, Sussex County became the home to the New Jersey Cardinals, a Class A-Short Season affiliate of Major League Baseball's St. Louis Cardinals franchise in 1994. The Cardinals, previously the Glens Falls Redbirds (1981–93) from upstate New York, won the New York–Penn League's championship in their 1994 inaugural season. They had one other winning season (in 2002) and in 2005 the owners sold the team—which was then moved to University Park, Pennsylvania and renamed the State College Spikes.[183] They are now affiliated with MLB's Pittsburgh Pirates franchise.[184] In 2006, Skylands Park became the home of the Sussex Skyhawks an affiliate of the Canadian American Association of Professional Baseball (or Can-Am League). The team were League Champions during the 2008 season. The team ceased operations after the 2010 season.[185]

See also

- List of Sussex County, New Jersey people

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Sussex County, New Jersey

References

Endnotes

- 1 2 3 Snyder, John P. The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries: 1606–1968, Bureau of Geology and Topography; Trenton, New Jersey; 1969. p. 229. Accessed May 31, 2012.

- 1 2 Sussex County, NJ, National Association of Counties. Accessed January 21, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 DP1 – Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data for Sussex County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed March 25, 2016.

- 1 2 3 State & County QuickFacts - Sussex County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed July 3, 2016.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ NJ Labor Market Views, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development, March 15, 2011. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 New Jersey: 2010 - Population and Housing Unit Counts; 2010 Census of Population and Housing, p. 6, CPH-2-32. United States Census Bureau, August 2012. Accessed August 29, 2016.

- 1 2 3 250 Highest Per Capita Personal Incomes of the 3113 Counties in the United States, 2010, U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. Accessed July 16, 2012.

- ↑ Hutchinson, Viola L. The Origin of New Jersey Place Names, New Jersey Public Library Commission, May 1945. Accessed October 11, 2015.

- ↑ Gannett, Henry. The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States, p. 294. United States Government Printing Office, 1905. Accessed October 11, 2015.

- ↑ Kraft, Herbert C. The Lenape-Delaware Indian Heritage: 10,000 B.C. to A.D. 2000. (Stanhope, New Jersey: Lenape Books, 2001).

- ↑ Goddard, Ives; and Trigger, Bruce G. (1978) "Delaware" in Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 15: Northeast. Washington. 213–239

- ↑ Grumet, Robert Steven. The Munsee Indians: A History from Civilization of the American Indian 262 (series). (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009).

- ↑ Otto, Paul. The Dutch-Munsee Encounter in America: The Struggle for Sovereignty in the Hudson Valley. (New York: Berghahn Books, 2006).

- ↑ Keenan, Jerry. Encyclopedia of American Indian Wars, 1492–1890. (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1999), 234; Moore, Charles. The Northwest Under Three Flags, 1635–1796. (New York and London: Harper & Brothers, 1900), 151.

- ↑ Weslager, Clinton A. The Delaware Indians: A History. (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1972).

- ↑ Decker, Amelia Stickney. That Ancient Trail. (Trenton, New Jersey: Privately published, 1942, reprinted Newton, New Jersey: Sussex County Historical Society, 2003).

- ↑ Chambers, Theodore Frelinghuysen. The Early Germans of New Jersey: Their History, Churches, and Genealogies (Dover, New Jersey, Dover Printing Company, 1895), passim.

- 1 2 Armstrong, William C. Pioneer Families of Northwestern New Jersey (Lambertville, New Jersey: Hunterdon House, 1979).

- ↑ Paterson, William. Laws of the State of New Jersey (Newark, New Jersey: Matthias Day, 1800), 15. Note: the "great pond" referenced in the legal boundaries of the act is an 18th-century reference to Lake Hopatcong.

- 1 2 State of New Jersey. Acts of the Legislature of the State of New Jersey, (1824), 146–147. The landmark used for drawing the boundary through Yellow Frame was the Presbyterian Church edifice torn down in 1898.

- ↑ Ricord, Frederick W. (editor). Biographical Encyclopedia: Successful Men of New Jersey. (New York: New Jersey Historical Publishing Co., 1896), 1:47.

- ↑ Woodside, Martin. Thomas A. Edison: The Man Who Lit Up the World. (New York: Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2007), 73–74.

- ↑ Edison Companies: Mining in The Thomas Edison Papers. Rutgers University. Accessed August 3, 2013.

- 1 2 Peterson, M. "Thomas Edison, Failure", in American Heritage of Invention & Technology (Winter 1991), 6(3):8-14.

- 1 2 "Edison and Ore Refining". Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Global History Network. August 3, 2009. Accessed September 24, 2011.

- ↑ "Thomas Alva Edison And The Concrete Piano" in American Heritage (August/September 1980), 31(5). Accessed August 3, 2013.

- ↑ "Cement" in The Thomas Edison Papers. Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Accessed August 3, 2013.

- 1 2 United States Congress. FOWLER, Samuel, (1779–1844) in Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774–present. Accessed August 3, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dunn, Pete J. Mine Hill in Franklin, and Sterling Hill in Ogdensburg, Sussex County, New Jersey: Mining history, 1765–1900: Final Report. 4 volumes. (Alexandria, Virginia: Smithsonian Institution, 2002).

- 1 2 Jones, Robert W. Jr. Nature's Hidden Rainbows : The Fluorescent Minerals of Franklin, New Jersey. (San Gabriel, California: Ultra-Violet Products, Inc., 1964).

- ↑ New Jersey State Legislature. Resolution declaring Franklin Borough as "Fluorescent Mineral Capitol of the World." (September 13, 1968).

- ↑ The Fluorescent Mineral Society. "Fluorescent Minerals". Accessed August 3, 2013.

- ↑ Truran, William R. Images of America: Franklin, Hamburg, Ogdensburg, and Hardyston. (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2004).

- 1 2 Squires, Patricia. "OGDENSBURG JOURNAL; Old Mine Transformed Into Museum", The New York Times, December 9, 1990. Accessed August 3, 2013.

- 1 2 Forstall, Richard L. Population of states and counties of the United States: 1790 to 1990 from the Twenty-one Decennial Censuses, pp. 108-109. United States Census Bureau, March 1996. ISBN 9780934213486. Accessed October 6, 2013.

- 1 2 "Elevations and Distances in the United States", United States Geological Survey. Accessed August 28, 2012.

- 1 2 "Sussex County Facts & Figures at a Glance" (fact sheet) Sussex County Clerk's Office. Accessed August 28, 2012.

- ↑ New Jersey County High Points, Peakbagger.com. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resource Conservation Service. Soil Survey of Sussex County, New Jersey (Washington, D.C.: 2009).

- ↑ Delaware River Basin Commission. "Section 6: Sussex County" from Flood Mitigation Plan for the Non-tidal, New Jersey section of the Delaware River Basin (November 2008), 244.

- ↑ Census 2010 U.S. Gazetteer Files: New Jersey Counties, United States Census Bureau, Backed up by the Internet Archive as of June 11, 2012. Accessed October 6, 2013.

- ↑ Only three counties are larger in terms of area: Ocean County (916 square miles/2,372 square kilometers) Burlington County (805 square miles/2,085 square kilometers), Atlantic County (561 square miles/1,453 square kilometers). See List of counties in New Jersey for a comparison.

- 1 2 3 Lucey, Carol S. Geology of Sussex County in Brief. (Trenton, New Jersey: New Jersey Geological Survey, November 1969), 21pp. Accessed August 28, 2012.

- ↑ Hatcher, Robert D. Jr. "Tracking lower-to-mid-to-upper crustal deformation processes through time and space through three Paleozoic orogenies in the Southern Appalachians using dated metamorphic assemblages and faults" in Abstracts with Programs (Geological Society of America), Vol. 40, No. 6, 513. Accessed August 28, 2012.

- ↑ Bartholomew, M.J., and Whitaker, A.E., 2010, The Alleghanian deformational sequence at the foreland junction of the Central and Southern Appalachians in Tollo, R.P., Bartholomew, M.J., Hibbard, J.P., and Karabinos, P.M., eds., From Rodinia to Pangea: The Lithotectonic Record of the Appalachian Region, GSA Memoir 206, p. 431-454.

- ↑ Dalton, Richard. New Jersey Geological Survey Information Circular: Physiographic Provinces of New Jersey (Trenton, New Jersey: Department of Environmental Protection, State of New Jersey, 2003, 2006). Accessed August 28, 2012.