Sudden infant death syndrome

| Sudden infant death syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Safe to Sleep logo | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics |

| ICD-10 | R95 |

| ICD-9-CM | 798.0 |

| OMIM | 272120 |

| DiseasesDB | 12633 |

| MedlinePlus | 001566 |

| eMedicine | emerg/407 ped/2171 |

| Patient UK | Sudden infant death syndrome |

| MeSH | D013398 |

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), also known as cot death or crib death, is the sudden unexplained death of a child less than one year of age.[1] Diagnosis requires that the death remains unexplained even after a thorough autopsy and detailed death scene investigation.[2] SIDS usually occurs during sleep.[3] Typically death occurs between the hours of 00:00 and 09:00.[4] There is usually no evidence of struggle and no noise produced.[5]

The exact cause of SIDS is unknown.[6] The requirement of a combination of factors including a specific underlying susceptibility, a specific time in development, and an environmental stressor has been proposed.[3][6] These environmental stressors may include sleeping on the stomach or side, overheating, and exposure to tobacco smoke.[6] Accidental suffocation such as during bed sharing or from soft objects may also play a role.[3][7] Another risk factor is being born before 39 weeks of gestation.[8] SIDS makes up about 80% of sudden and unexpected infant deaths (SUIDs), with other causes including infections, genetic disorders, and heart problems. While child abuse in the form of intentional suffocation may be misdiagnosed as SIDS, this is believed to make up less than 5% of cases.[3]

The most effective method of reducing the risk of SIDS is putting a child less than one year old on their back to sleep.[8] Other measures include a firm mattress separate from but close to caregivers, no loose bedding, a relatively cool sleeping environment, using a pacifier, and avoiding exposure to tobacco smoke.[9] Breastfeeding and immunization may also be preventive.[9][10] Measures not shown to be useful include positioning devices and baby monitors.[9][10] Evidence is not sufficient for the use of fans.[9] Grief support for families impacted by SIDS is important, as the death of the infant is sudden, without witnesses, and often associated with an investigation.[3]

Rates of SIDS vary nearly tenfold in developed countries from one in a thousand to one in ten thousand.[3] Globally it resulted in about 15,000 deaths in 2013 down from 22,000 deaths in 1990.[11] SIDS was the third leading cause of death in children less than one year old in the United States in 2011.[12] It is the most common cause of death between one month and one year of age.[8] About 90% of cases happen before six months of age, with it being most frequent between two months and four months of age.[3][8] It is more common in boys than girls.[8]

Definition

SIDS is a diagnosis of exclusion and should be applied to only those cases in which an infant's death is sudden and unexpected, and remains unexplained after the performance of an adequate postmortem investigation, including:

- an autopsy (by an experienced pediatric pathologist, if possible);

- investigation of the death scene and circumstances of the death;

- exploration of the medical history of the infant and family.

After investigation, some of these infant deaths are found to be caused by accidental suffocation, hyperthermia or hypothermia, neglect or some other defined cause.[13]

Australia and New Zealand are shifting to the term "sudden unexpected death in infancy" (SUDI) for professional, scientific, and coronial clarity.

The term SUDI is now often used instead of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) because some coroners prefer to use the term 'undetermined' for a death previously considered to be SIDS. This change is causing diagnostic shift in the mortality data.[14]

In addition, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recently proposed that such deaths be called "sudden unexpected infant deaths" (SUID) and that SIDS is a subset of SUID.[15]

Age

SIDS has a 4-parameter lognormal age distribution that spares infants shortly after birth — the time of maximal risk for almost all other causes of non-trauma infant death.

By definition, SIDS deaths occur under the age of one year, with the peak incidence occurring when the infant is at 2 to 4 months of age. This is considered a critical period because the infant's ability to rouse from sleep is not yet mature.[3]

Risk factors

The cause of SIDS is unknown. Although studies have identified risk factors for SIDS, such as putting infants to bed on their stomachs, there has been little understanding of the syndrome's biological process or its potential causes. The frequency of SIDS does appear to be influenced by social, economic, and cultural factors, such as maternal education, race or ethnicity, and poverty.[16] SIDS is believed to occur when an infant with an underlying biological vulnerability, who is at a critical development age, is exposed to an external trigger.[3] The following risk factors generally contribute either to the underlying biological vulnerability or represent an external trigger:

Tobacco smoke

SIDS rates are higher for infants of mothers who smoke during pregnancy.[17][18] SID correlates with levels of nicotine and derivatives in the infant.[19] Nicotine and derivatives cause significant alterations in fetal neurodevelopment.[20]

Sleeping

Placing an infant to sleep while lying on the stomach or the side increases the risk.[9] This increased risk is greatest at two to three months of age.[9] Elevated or reduced room temperature also increases the risk,[21] as does excessive bedding, clothing, soft sleep surfaces, and stuffed animals.[22] Bumper pads may increase the risk and, as there is little evidence of benefit from their use, they are not recommended.[9]

Sharing a bed with parents or siblings increases the risk for SIDS.[23] This risk is greatest in the first three months of life, when the mattress is soft, when one or more persons share the infant's bed, especially when the bed partners are using drugs or alcohol or are smoking.[9] The risk remains, however, even in parents who do not smoke or use drugs.[24] The American Academy of Pediatrics thus recommends "room-sharing without bed-sharing", stating that such an arrangement can decrease the risk of SIDS by up to 50%. Furthermore, the Academy recommended against devices marketed to make bed-sharing "safe", such as in-bed co-sleepers.[25]

Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding is associated with a lower risk of SIDS.[26] It is not clear if co-sleeping among mothers who breastfeed without any other risk factors increased SIDS risk.[27]

Pregnancy and infant factors

SIDS rates decrease with increasing maternal age, with teenage mothers at greatest risk.[17] Delayed or inadequate prenatal care also increases risk.[17] Low birth weight is a significant risk factor. In the United States from 1995 to 1998, the SIDS death rate for infants weighing 1000–1499 g was 2.89/1000, while for a birth weight of 3500–3999 g, it was only 0.51/1000.[28][29] Premature birth increases the risk of SIDS death roughly fourfold.[17][28] From 1995 to 1998, the U.S. SIDS rate for births at 37–39 weeks of gestation was 0.73/1000, while the SIDS rate for births at 28–31 weeks of gestation was 2.39/1000.[28]

Anemia has also been linked to SIDS[30] (note, however, that per item 6 in the list of epidemiologic characteristics below, extent of anemia cannot be evaluated at autopsy because an infant's total hemoglobin can only be measured during life.[31]). SIDS incidence rises from zero at birth, is highest from two to four months of age, and declines toward zero after the infant's first year.[32] Baby boys have a ~50% higher risk of SIDS than girls.[33]

Genetics

Genetics plays a role, as SIDS is more prevalent in males.[34][35] There is a consistent 50% male excess in SIDS per 1000 live births of each sex. Given a 5% male excess birth rate, there appears to be 3.15 male SIDS cases per 2 female, for a male fraction of 0.61.[34][35] This value of 61% in the US is an average of 57% black male SIDS, 62.2% white male SIDS and 59.4% for all other races combined. Note that when multiracial parentage is involved, infant race is arbitrarily assigned to one category or the other; most often it is chosen by the mother. The X-linkage hypothesis for SIDS and the male excess in infant mortality have shown that the 50% male excess could be related to a dominant X-linked allele, occurring with a frequency of 1⁄3 that is protective of transient cerebral anoxia. An unprotected male would occur with a frequency of 2⁄3 and an unprotected female would occur with a frequency of 4⁄9.

About 10 to 20% of SIDS cases are believed to be due to channelopathies, which are inherited defects in the ion channels which play an important role in the contraction of the heart.[36]

Alcohol

Parents who drink alcohol is linked to SIDS.[37] A particular study found a positive correlation between the two during New Years celebrations and weekends.[38]

Other

There is a tentative link with Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli.[39]

Vaccinations do not increase the risk of SIDS; contrarily, they are linked to a 50% lower risk of SIDS.[40][41]

A 1998 report found that antimony- and phosphorus-containing compounds used as fire retardants in PVC and other cot mattress materials are not a cause of SIDS.[42] The report also states that toxic gas can not be generated from antimony in mattresses and that babies suffered SIDS on mattresses that did not contain the compound.

A set of risk factors SIDS has been identified with: seasonality: winter maximum, summer minimum; increasing SIDS rate with live birth order; low increased risk of SIDS in subsequent siblings of SIDS; apparent life-threatening events (ALTE) are not a risk factor for subsequent SIDS; SIDS risk is greatest during sleep.[43]

Differential diagnosis

Some conditions that are often undiagnosed and could be confused with or comorbid with SIDS include:

- medium-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency (MCAD deficiency);[44]

- infant botulism;[45]

- long QT syndrome (accounting for less than 2% of cases);[46]

- Helicobacter pylori bacterial infections;[47]

- shaken baby syndrome and other forms of child abuse;[48][49]

- overlaying, child smothering during carer's sleep[50]

For example, an infant with MCAD deficiency could have died by "classical SIDS" if found swaddled and prone with head covered in an overheated room where parents were smoking. Genes indicating susceptibility to MCAD and Long QT syndrome do not protect an infant from dying of classical SIDS. Therefore, presence of a susceptibility gene, such as for MCAD, means the infant may have died either from SIDS or from MCAD deficiency. It is currently impossible for the pathologist to distinguish between them.

A 2010 study looked at 554 autopsies of infants in North Carolina that listed SIDS as the cause of death, and suggested that many of these deaths may have been due to accidental suffocation. The study found that 69% of autopsies listed other possible risk factors that could have led to death, such as unsafe bedding or sleeping with adults.[51]

Several instances of infanticide have been uncovered where the diagnosis was originally SIDS.[52][53] Estimate of the percentage of SIDS deaths that are actually infanticide vary from less than 1% to up to 5% of cases.[54]

Some have underestimated the risk of two SIDS deaths occurring in the same family and the Royal Statistical Society issued a media release refuting this expert testimony in one UK case in which the conviction was subsequently overturned.[55]

Prevention

A number of measures have been found to be effective in preventing SIDS including changing the sleeping position, breastfeeding, limiting soft bedding, immunizing the infant and using pacifiers.[9] The use of electronic monitors has not been found to be useful as a preventative strategy.[9] The effect that fans might have on the risk of SIDS has not been studied well enough to make any recommendation about them.[9] Evidence regarding swaddling is unclear regarding SIDS.[9] A 2016 review found tentative evidence that swaddling increases risk of SIDS, especially among babies placed on their stomachs or side while sleeping.[56]

Sleep positioning

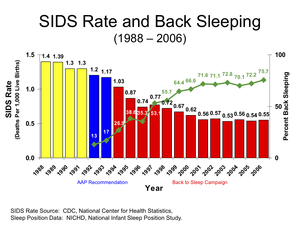

Sleeping on the back has been found to reduce the risk of SIDS.[57] It is thus recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics and promoted as a best practice by the US National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) "Safe to Sleep" campaign. The incidence of SIDS has fallen in a number of countries in which this recommendation has been widely adopted.[58] Sleeping on the back does not appear to increase the risk of choking even in those with gastroesophageal reflux disease.[9] While infants in this position may sleep more lightly this is not harmful.[9] Sharing the same room as one's parents but in a different bed may decrease the risk by half.[9]

Pacifiers

The use of pacifiers appears to decrease the risk of SIDS although the reason is unclear.[9] The American Academy of Pediatrics considers pacifier use to prevent SIDS to be reasonable.[9] Pacifiers do not appear to affect breastfeeding in the first four months, even though this is a common misconception.[59]

Bedding

Product safety experts advise against using pillows, overly soft mattresses, sleep positioners, bumper pads (crib bumpers), stuffed animals, or fluffy bedding in the crib and recommend instead dressing the child warmly and keeping the crib "naked."[60]

Blankets or other clothing should not be placed over a babies's head.[61]

Sleep sacks

In colder environments where bedding is required to maintain a baby's body temperature, the use of a "baby sleep bag" or "sleep sack" is becoming more popular. This is a soft bag with holes for the baby's arms and head. A zipper allows the bag to be closed around the baby. A study published in the European Journal of Pediatrics in August 1998[62] has shown the protective effects of a sleep sack as reducing the incidence of turning from back to front during sleep, reinforcing putting a baby to sleep on its back for placement into the sleep sack and preventing bedding from coming up over the face which leads to increased temperature and carbon dioxide rebreathing. They conclude in their study, "The use of a sleeping-sack should be particularly promoted for infants with a low birth weight." The American Academy of Pediatrics also recommends them as a type of bedding that warms the baby without covering its head.[63]

Vaccination

A large investigation into diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccination and potential SIDS association by Berlin School of Public Health, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin concluded: "Increased DTP immunisation coverage is associated with decreased SIDS mortality. Current recommendations on timely DTP immunisation should be emphasised to prevent not only specific infectious diseases but also potentially SIDS."[64]

Many other studies have also reached conclusions that vaccinations reduce the risk of SIDS. Studies generally show that SIDS risk is approximately halved by vaccinations.[65][66][67][68][69]

Management

Families who are impacted by SIDS should be offered emotional support and grief counseling.[70] The experience and manifestation of grief at the loss of an infant are impacted by cultural and individual differences.[71]

Epidemiology

Globally SIDS resulted in about 22,000 deaths as of 2010, down from 30,000 deaths in 1990.[72] Rates vary significantly by population from 0.05 per 1000 in Hong Kong to 6.7 per 1000 in American Indians.[73]

SIDS was responsible for 0.54 deaths per 1,000 live births in the US in 2005.[28] It is responsible for far fewer deaths than congenital disorders and disorders related to short gestation, though it is the leading cause of death in healthy infants after one month of age.

SIDS deaths in the US decreased from 4,895 in 1992 to 2,247 in 2004.[74] But, during a similar time period, 1989 to 2004, SIDS being listed as the cause of death for sudden infant death (SID) decreased from 80% to 55%.[74] According to John Kattwinkel, chairman of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Special Task Force on SIDS "A lot of us are concerned that the rate (of SIDS) isn't decreasing significantly, but that a lot of it is just code shifting".[74]

Race

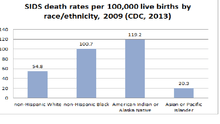

In 2013, there are persistent disparities in SIDS deaths among racial and ethnic groups in the U.S. In 2009, the rates of death range from 20.3 for Asian/Pacific Islander to 119.2 for American Indians/Alaska Native. African American infants have a 24% greater risk of having a SIDS related death [75] and experience a 2.5 greater incidence of SIDS than in Caucasian infants.[76] Rates are per 100,000 live births and enable more accurate comparison across groups of different total population size.

Research suggests that factors which contribute more directly to SIDS risk—maternal age, exposure to smoking, safe sleep practices, etc.—vary by racial and ethnic group and therefore risk exposure also varies by these groups.[3] Risk factors associated with prone sleeping patterns of African American families include mother’s age, household poverty index, rural/urban status of residence, and infant’s age. More than 50% of African American infants were placed in non-recommended sleeping positions according to a study completed in South Carolina.[77] Cultural factors can be protective as well as problematic.[78]

The rate per 1000 births varies in different areas of the world:[21][79] Central Americans and South Americans - 0.20 Asian/Pacific Islanders - 0.28 Mexicans - 0.24 Puerto Ricans - 0.53 Whites - 0.51 African Americans - 1.08 American Indian - 1.24

Society and culture

Much of the media portrayal of infants shows them in non-recommended sleeping positions.[9]

See also

References

- ↑ "Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS): Overview". National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 27 June 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ↑ "Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Sudden Infant Death". Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Kinney HC, Thach BT (2009). "The sudden infant death syndrome". N. Engl. J. Med. 361 (8): 795–805. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0803836. PMC 3268262

. PMID 19692691.

. PMID 19692691. - ↑ Optiz, Enid Gilbert-Barness, Diane E. Spicer, Thora S. Steffensen ; foreword by John M. (2013). Handbook of pediatric autopsy pathology (Second edition. ed.). New York, NY: Springer New York. p. 654. ISBN 9781461467113.

- ↑ Scheimberg, edited by Marta C. Cohen, Irene (2014). The Pediatric and perinatal autopsy manual. p. 319. ISBN 9781107646070.

- 1 2 3 "What causes SIDS?". National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 12 April 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ↑ "Ways To Reduce the Risk of SIDS and Other Sleep-Related Causes of Infant Death". NICHD. 20 January 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "How many infants die from SIDS or are at risk for SIDS?". National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 19 November 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Moon RY, Fu L (July 2012). "Sudden infant death syndrome: an update.". Pediatrics in review / American Academy of Pediatrics. 33 (7): 314–20. doi:10.1542/pir.33-7-314. PMID 22753789.

- 1 2 "How can I reduce the risk of SIDS?". National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 22 August 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ↑ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.". Lancet. 385: 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604

. PMID 25530442.

. PMID 25530442. - ↑ Hoyert DL, Xu JQ (2012). "Deaths: Preliminary data for 2011" (PDF). National vital statistics reports. National Center for Health Statistics. 61 (6): 8.

- ↑ "Sudden Unexpected Infant Death and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome: About SUID and SIDS". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- ↑ NZ Ministry of Health Archived December 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Sudden Unexpected Infant Death" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- ↑ Pickett, KE, Luo, Y, Lauderdale, DS. Widening Social Inequalities in Risk for Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Am J Public Health 2005;94(11):1976–1981. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.059063

- 1 2 3 4 Sullivan FM, Barlow SM (2001). "Review of risk factors for Sudden Infant Death Syndrome". Paediatric Perinatal Epidemiology. 15 (2): 144–200. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00330.x. PMID 11383580.

- ↑ Office of the Surgeon General of the United States Report on Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke(PDF)

- ↑ Bajanowski T.; Brinkmann B.; Mitchell E.; Vennemann M.; Leukel H.; Larsch K.; Beike J.; Gesid G. (2008). "Nicotine and cotinine in infants dying from sudden infant death syndrome". International journal of legal medicine. 122 (1): 23–28. doi:10.1007/s00414-007-0155-9. PMID 17285322.

- ↑ Lavezzi AM, Corna MF, Matturri L (July 2010). "Ependymal alterations in sudden intrauterine unexplained death and sudden infant death syndrome: possible primary consequence of prenatal exposure to cigarette smoking". Neural Dev. 19 (5): 17. doi:10.1186/1749-8104-5-17. PMC 2919533

. PMID 20642831.

. PMID 20642831. - 1 2 Moon RY, Horne RS, Hauck FR (November 2007). "Sudden infant death syndrome". Lancet. 370 (9598): 1578–87. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61662-6. PMID 17980736.

- ↑ Fleming PJ, Levine MR, Azaz Y, Wigfield R, Stewart AJ (June 1993). "Interactions between thermoregulation and the control of respiration in infants: possible relationship to sudden infant death". Acta Paediatr Suppl. 82 (Suppl 389): 57–9. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.1993.tb12878.x. PMID 8374195.

- ↑ McIntosh CG, Tonkin SL, Gunn AJ (2009). "What is the mechanism of sudden infant deaths associated with co-sleeping?". N. Z. Med. J. 122 (1307): 69–75. PMID 20148046.

- ↑ Carpenter, R; McGarvey, C; Mitchell, EA; Tappin, DM; Vennemann, MM; Smuk, M; Carpenter, JR (2013). "Bed sharing when parents do not smoke: is there a risk of SIDS? An individual level analysis of five major case-control studies". BMJ Open. 3 (5): e002299. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002299. PMID 23793691.

- ↑ Moon RY (November 2011). "SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: expansion of recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment.". Pediatrics. 128 (5): 1030–9. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2284. PMID 22007004.

- ↑ Hauck, FR; Thompson, JM; Tanabe, KO; Moon, RY; Vennemann, MM (July 2011). "Breastfeeding and reduced risk of sudden infant death syndrome: a meta-analysis.". Pediatrics. 128 (1): 103–10. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-3000. PMID 21669892.

- ↑ Fleming, PJ; Blair, PS (2 February 2015). "Making informed choices on co-sleeping with your baby.". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 350: h563. doi:10.1136/bmj.h563. PMID 25643704.

- 1 2 3 4 "Cdc Wonder". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2010-02-24. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ↑ Hunt CE (November 2007). "Small for gestational age infants and sudden infant death syndrome: a confluence of complex conditions". Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 92 (6): F428–9. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.112243. PMC 2675383

. PMID 17951549.

. PMID 17951549. - ↑ Poets CF, Samuels MP, Wardrop CA, Picton-Jones E, Southall DP (April 1992). "Reduced haemoglobin levels in infants presenting with apparent life-threatening events—a retrospective investigation". Acta Paediatr. 81 (4): 319–21. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.1992.tb12234.x. PMID 1606392.

- ↑ Giulian GG, Gilbert EF, Moss RL (April 1987). "Elevated fetal hemoglobin levels in sudden infant death syndrome". N Engl J Med. 316 (18): 1122–6. doi:10.1056/NEJM198704303161804. PMID 2437454.

- ↑ Mage DT (1996). "A probability model for the age distribution of SIDS". J Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Infant Mortal. 1: 13–31.

- ↑ Mage DT, Donner M. A genetic basis for the sudden infant death syndrome sex ratio, Med Hypotheses 1997;48:137–142.

- 1 2 See CDC WONDER online database and http://www3.who.int/whosis/menu.cfm?path=whosis,inds,mort&language=english for data on SIDS by gender in the US and throughout the world.

- 1 2 Mage DT, Donner EM (September 2004). "The fifty percent male excess of infant respiratory mortality". Acta Paediatr. 93 (9): 1210–5. doi:10.1080/08035250410031305. PMID 15384886.

- ↑ Behere, SP; Weindling, SN (2014). "Inherited arrhythmias: The cardiac channelopathies.". Annals of Pediatric Cardiology. 8 (3): 210–20. doi:10.4103/0974-2069.164695. PMC 4608198

. PMID 26556967.

. PMID 26556967. - ↑ Van Nguyen, JM; Abenhaim, HA (October 2013). "Sudden infant death syndrome: review for the obstetric care provider.". American journal of perinatology. 30 (9): 703–14. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1331035. PMID 23292938.

- ↑ Phillips, DP; Brewer, KM; Wadensweiler, P (March 2011). "Alcohol as a risk factor for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).". Addiction (Abingdon, England). 106 (3): 516–25. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03199.x. PMID 21059188.

- ↑ Weber MA, Klein NJ, Hartley JC, Lock PE, Malone M, Sebire NJ (May 31, 2008). "Infection and sudden unexpected death in infancy: a systematic retrospective case review.". Lancet. 371 (9627): 1848–53. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60798-9. PMID 18514728.

- ↑ Vennemann, MM; Höffgen, M; Bajanowski, T; Hense, HW; Mitchell, EA (21 June 2007). "Do immunisations reduce the risk for SIDS? A meta-analysis". Vaccine. 25 (26): 4875–9. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.02.077. PMID 17400342.

- ↑ "Vaccine Safety: Common Concerns: Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 28 August 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ↑ See FSID Press release.

- ↑ Mage DT, Donner EM (2004). "Is SIDS at Borkmann's Point?". Medical Hypotheses and Research. 1 (2/3): 131–7.

- ↑ Yang Z, Lantz PE, Ibdah JA (December 2007). "Post-mortem analysis for two prevalent beta-oxidation mutations in sudden infant death". Pediatr Int. 49 (6): 883–7. doi:10.1111/j.1442-200X.2007.02478.x. PMID 18045290.

- ↑ Nevas M, Lindström M, Virtanen A, Hielm S, Kuusi M, Arnon SS, Vuori E, Korkeala H (January 2005). "Infant botulism acquired from household dust presenting as sudden infant death syndrome". J. Clin. Microbiol. 43 (1): 511–3. doi:10.1128/JCM.43.1.511-513.2005. PMC 540168

. PMID 15635031.

. PMID 15635031. - ↑ Millat G, Kugener B, Chevalier P, Chahine M, Huang H, Malicier D, Rodriguez-Lafrasse C, Rousson R (May 2009). "Contribution of long-QT syndrome genetic variants in sudden infant death syndrome". Pediatr Cardiol. 30 (4): 502–9. doi:10.1007/s00246-009-9417-2. PMID 19322600.

- ↑ Stray-Pedersen A, Vege A, Rognum TO (October 2008). "Helicobacter pylori antigen in stool is associated with SIDS and sudden infant deaths due to infectious disease". Pediatr. Res. 64 (4): 405–10. doi:10.1203/PDR.0b013e31818095f7. PMID 18535491.

- ↑ Bajanowski T, Vennemann M, Bohnert M, Rauch E, Brinkmann B, Mitchell EA (July 2005). "Unnatural causes of sudden unexpected deaths initially thought to be sudden infant death syndrome". Int. J. Legal Med. 119 (4): 213–6. doi:10.1007/s00414-005-0538-8. PMID 15830244.

- ↑ Du Chesne A, Bajanowski T, Brinkmann B (1997). "[Homicides without clues in children]". Arch Kriminol (in German). 199 (1–2): 21–6. PMID 9157833.

- ↑ Williams FL, Lang GA, Mage DT (2001). "Sudden unexpected infant deaths in Dundee, 1882–1891: overlying or SIDS?". Scottish medical journal. 46 (2): 43–47. PMID 11394337.

- ↑ http://www.charlotteobserver.com/sids/

- ↑ Glatt, John (2000). Cradle of Death: A Shocking True Story of a Mother, Multiple Murder, and SIDS. Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-97302-0.

- ↑ Havill, Adrian (2002). While Innocents Slept: A Story of Revenge, Murder, and SIDS. Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-97517-1.

- ↑ Hymel KP (July 2006). "Distinguishing sudden infant death syndrome from child abuse fatalities.". Pediatrics. 118 (1): 421–7. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1245. PMID 16818592.

- ↑ "About Statistics and the Law" (Website). Royal Statistical Society. (2001-10-23) Retrieved on 2007-09-22

- ↑ Pease, AS; Fleming, PJ; Hauck, FR; Moon, RY; Horne, RS; L'Hoir, MP; Ponsonby, AL; Blair, PS (June 2016). "Swaddling and the Risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome: A Meta-analysis.". Pediatrics. 137 (6). doi:10.1542/peds.2015-3275. PMID 27244847.

Limited evidence suggested swaddling risk increased with infant age and was associated with a twofold risk for infants aged >6 months.

- ↑ Mitchell EA (November 2009). "SIDS: past, present and future.". Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). 98 (11): 1712–9. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01503.x. PMID 19807704.

- ↑ Mitchell EA, Hutchison L, Stewart AW (July 2007). "The continuing decline in SIDS mortality". Arch Dis Child. 92 (7): 625–6. doi:10.1136/adc.2007.116194. PMC 2083749

. PMID 17405855.

. PMID 17405855. - ↑ Jaafar SH, Jahanfar S, Angolkar M, Ho JJ (Jul 11, 2012). "Effect of restricted pacifier use in breastfeeding term infants for increasing duration of breastfeeding.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 7: CD007202. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007202.pub3. PMID 22786506.

- ↑ "What Can Be Done?". American SIDS Institute.

- ↑ Syndrome, Task Force on Sudden Infant Death (24 October 2016). "SIDS and Other Sleep-Related Infant Deaths: Updated 2016 Recommendations for a Safe Infant Sleeping Environment". Pediatrics: e20162938. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-2938. ISSN 0031-4005.

- ↑ L'Hoir MP, Engelberts AC, van Well GT, McClelland S, Westers P, Dandachli T, Mellenbergh GJ, Wolters WH, Huber J (1998). "Risk and preventive factors for cot death in The Netherlands, a low-incidence country". Eur. J. Pediatr. 157 (8): 681–8. doi:10.1007/s004310050911. PMID 9727856.

- ↑ "The Changing Concept of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome: Diagnostic Coding Shifts, Controversies Regarding the Sleeping Environment, and New Variables to Consider in Reducing Risk". American Academy of Pediatrics. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- ↑ Müller-Nordhorn, Jacqueline; Hettler-Chen, Chih-Mei; Keil, Thomas; Muckelbauer, Rebecca (28 January 2015). "Association between sudden infant death syndrome and diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis immunisation: an ecological study". BMC Pediatrics. 15 (1). doi:10.1186/s12887-015-0318-7.

- ↑ Mitchell, E A; Stewart, A W; Clements, M (1 December 1995). "Immunisation and the sudden infant death syndrome. New Zealand Cot Death Study Group.". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 73 (6): 498–501. doi:10.1136/adc.73.6.498.

- ↑ Fleming, P. J (7 April 2001). "The UK accelerated immunisation programme and sudden unexpected death in infancy: case-control study". BMJ. 322 (7290): 822–822. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7290.822.

- ↑ Vennemann, M.M.T.; Höffgen, M.; Bajanowski, T.; Hense, H.-W.; Mitchell, E.A. (2007). "Do immunisations reduce the risk for SIDS? A meta-analysis". Vaccine. 25 (26): 4875–9. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.02.077. PMID 17400342.

- ↑ Hoffman, HJ; Hunter, JC; Damus, K; Pakter, J; Peterson, DR; van Belle, G; Hasselmeyer, EG (April 1987). "Diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis immunization and sudden infant death: results of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Cooperative Epidemiological Study of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome risk factors.". Pediatrics. 79 (4): 598–611. PMID 3493477.

- ↑ Carvajal, A; Caro-Patón, T; Martín de Diego, I; Martín Arias, LH; Alvarez Requejo, A; Lobato, A (4 May 1996). "[DTP vaccine and infant sudden death syndrome. Meta-analysis].". Medicina clinica. 106 (17): 649–52. PMID 8691909.

- ↑ Adams SM, Good MW, Defranco GM (2009). "Sudden infant death syndrome". Am Fam Physician. 79 (10): 870–4. PMID 19496386.

- ↑ Koopmans L, Wilson T, Cacciatore J, et al. (Jun 13, 2013). "Support for mothers, fathers and families after perinatal death". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000452.pub3.

- ↑ Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, et al. (Dec 15, 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010.". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. PMID 23245604.

- ↑ Sharma BR (March 2007). "Sudden infant death syndrome: a subject of medicolegal research.". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 28 (1): 69–72. doi:10.1097/01.paf.0000220934.18700.ef. PMID 17325469.

- 1 2 3 Bowman L, Hargrove T. Exposing Sudden Infant Death In America. Scripps Howard News Service. http://dailycamera.com/news/2007/oct/08/saving-babies-exposing-sudden-infant-death-in/

- ↑ Powers, D. A.; Song, S. (2009). "Absolute change in cause-specific infant mortality for blacks and whites in the US: 1983–2002". tion Research and Policy Review. 28 (6): 817–851. doi:10.1007/s11113-009-9130-0.

- ↑ Pollack, H. A.; Frohna, J. G. (2001). "A competing risk model of sudden infant death syndrome incidence in two US birth cohorts". The Journal of Pediatrics. 138 (5): 661–667. doi:10.1067/mpd.2001.112248.

- ↑ Smith, M. G.; Liu, J.; Helms, K. H.; Wilkerson, K. L. (2012). "Racial differences in trends and predictors of infant sleep positioning in south carolina, 1996–2007". Maternal and Child Health Journal. 15 (1): 72–82. doi:10.1007/s10995-010-0718-0.

- ↑ Brathwaite-Fisher, T, Bronheim, S. Cultural Competence and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome and Other Infant Death: A Review of the Literature from 1990–2000. National Center for Cultural Competence, Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development 2001. DOI: http://gucchd.georgetown.edu/72396.html

- ↑ Burnett, Lynn Barkley. "Sudden Infant Death Syndrom". Medscape.

Further reading

- Ottaviani, G. (2014). Crib death – Sudden infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). Sudden infant and perinatal unexplained death: the pathologist's viewpoint. Berlin Heidelberg, Germany: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-08346-9.

- Joan Hodgman; Toke Hoppenbrouwers (2004). SIDS. Calabasas, Calif: Monte Nido Press. ISBN 0-9742663-0-2.

- Lewak N. "Book Review: SIDS". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 158 (4): 405. doi:10.1001/archpedi.158.4.405.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sudden infant death syndrome. |