Substitute good

In consumer theory, substitute goods or substitutes are products that a consumer perceives as similar or comparable, so that having more of one product makes them desire less of the other product. Formally, X and Y are substitutes if, when the price of X rises, the demand for Y rises.

Potatoes from different farms are an example: if the price of one farm's potatoes goes up, then it can be presumed that fewer people will buy potatoes from that farm and source them from another farm instead.

There are different degrees of substitutability. For example, a car and a bicycle may substitute to some extent: if the price of motor fuel increases considerably, one may expect that some people will switch to bicycles.

Introduction

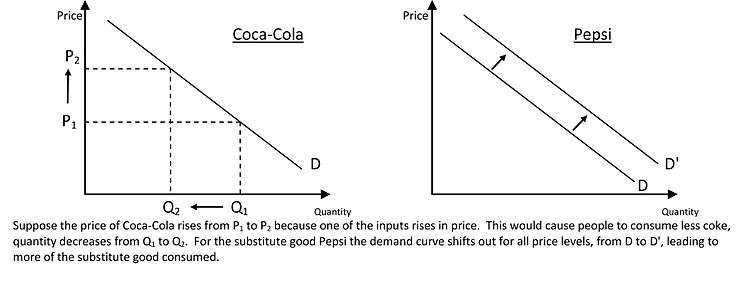

In economics, one way that two or more goods can be classified is by examining the relationship of the demand schedules when the price of one good changes. This relationship between demand schedules leads to classification of goods as either substitutes or complements. Substitute goods are goods which, as a result of changed conditions, may replace each other in use (or consumption).[1] A substitute good, in contrast to a complementary good, is a good with a positive cross elasticity of demand. This means a good's demand is increased when the price of another good is increased. Conversely, the demand for a good is decreased when the price of another good is decreased. If goods A and B are substitutes, an increase in the price of A will result in a leftward movement along the demand curve of A and cause the demand curve for B to shift out. A decrease in the price of A will result in a rightward movement along the demand curve of A and cause the demand curve for B to shift in.

Examples of substitute goods include margarine and butter, tea and coffee. Substitute goods not only occur on the consumer side of the market but also the producer side. Substitutable producer goods would include: petroleum and natural gas (used for heating or electricity). The degree to which a good has a perfect substitute depends on how specifically the good is defined. Take for example, the demand for Rice Krispies cereal, which is a very narrowly defined good as compared to the demand for cereal generally. The fact that one good is substitutable for another has immediate economic consequences: insofar as one good can be substituted for another, the demands for the two kinds of good will be interrelated by the fact that customers can trade off one good for the other if it becomes advantageous to do so.

Increase in price

An increase in price (ceteris paribus) will result in an increase in demand for its substitute goods. If two goods have a high substitutability, the change in demand will be much greater. Thus, economists can predict that a spike in the cost of a particular brand of detergent is likely to result in a large change in demand for other brands, whereas a change in the price of pencils will have a much smaller effect on the demand for other stationery, such as pens on legal documents or pencils on most high-school maths homework.

Different types

Substitutability

It is important to note that when speaking about substitute goods one is referring to two different kinds of goods; so the "substitutability" of one good for another is always a matter of degree. One good is a perfect substitute for another only if it can be used in exactly the same way. In that case the utility of a combination is an increasing function of the sum of the two amounts, and theoretically, in the case of a price difference, there would be no demand for the more expensive good.

In microeconomics, two types of substitutes are being distinguished, gross substitutes and net substitutes. Good is said to be gross substitute of good if

Goods X and Y are said to be net substitutes if

where is a utility function for the two goods.[1]

Categorization

Substitutes differ with respect to their category membership. Within-category substitutes are goods that are members of the same taxonomic category, goods sharing common attributes (e.g., chocolate, chairs, station wagons, etc.). Cross-category substitutes are goods that are members of different taxonomic categories but can satisfy the same goal. A person who cannot have the chocolate that she desires, for example, might instead buy ice cream to satisfy her goal to have a dessert.[2]

Substitutability of a good

Goods that are completely substitutable with each other are called perfect substitutes. They may be characterized as goods having a linear utility function or a constant marginal rate of substitution.[3]

Writeable compact disks from different manufacturers are often considered to be perfect substitutes. As the price of one brand of CD rises, consumers will be expected to substitute other brands of CD in a one-to-one fashion. This means that the total quantity of CDs purchased would not change.

Imperfect substitutes have a lesser level of substitutability, and therefore exhibit variable marginal rates of substitution along the consumer indifference curve. The consumption points on the curve offer the same level of utility as before but the compensation now depends on the starting point of the substitution. An example of such a product is the soft drink. As the price of Coca-Cola rises, consumers could be expected to substitute Pepsi. However, many consumers prefer one brand of soft drink over the other. Consumers who prefer Coke to Pepsi, for example, will not trade between them in a one-to-one fashion. Rather, a consumer would be willing to give relatively large amounts of Pepsi in exchange for relatively small amounts of Coke.

People exhibit a strong preference for within-category substitutes to cross-category substitutes. Across a ten sets of different foods, a majority of research participants (79.7%) believed that a within-category substitute would better satisfy their craving for a food they could not have than a cross-category substitute. Unable to acquire a desired Godiva chocolate, for instance, a majority reported that they would prefer to eat a store-brand chocolate (a within-category substitute) than a chocolate-chip granola bar (a cross-category substitute). This preference for within-category substitutes appears, however, to be misguided. Because within-category substitutes are more similar to the missing good, their inferiority to it is more noticeable. This creates a negative contrast effect, and leads within-category substitutes to be less satisfying substitutes than cross-category substitutes.[2]

Monopolistic competition

Many markets for commonly used goods feature products which are perfectly substitutable yet are differently branded and marketed, a condition referred to as monopolistic competition. A good example may be the comparison between store brand and name brand versions of medications - the products may be identical but the packaging is differentiated by the vendors. Since the goods are essentially alike, the only genuine difference between them is the price - their vendors rely primarily on price and branding to effect sales. In those sectors consumer choice is usually driven by discriminate according to lowest price, with higher-priced variants relying on a sense of exclusivity created by slicker branding to maintain competitiveness.

|

|

Perfect substitutability is significant in the era of deregulation, since there are usually several competing providers in a field (e.g. electricity suppliers) each retailing exactly the same product. The result is often aggressive price competition between the retailers.

Perfect competition

One of the requirements for perfect competition is that the products of competing firms should be perfect substitutes. When this condition is not satisfied, the market is characterized by product differentiation.

Types of substitute goods

Unit-demand goods are goods from which the consumer wants only a single item. If the consumer has two items, then his utility is the maximum of the utilities he gains from each of these items. For example, consider a certain consumer that only wants a means of transportation, which may be either a car or a bicycle. His utility from a car is 100 and from a bicycle is 50. If he has both a car and a bicycle, then he uses only the car so his utility is 100. Unit-demand goods are always substitutes, since if the price of one good increases, the consumer will tend to want the other good (Laizer 2016).

See also

- Ersatz, the original German word

- Competitive equilibrium

- List of economics topics

References

- 1 2 Nicholson, Walter (1998). Microeconomic Theory. The Dryden Press.

- 1 2 Huh, Young Eun; Vosgerau, Joachim; Morewedge, Carey K. (2016-06-01). "More Similar but Less Satisfying Comparing Preferences for and the Efficacy of Within- and Cross-Category Substitutes for Food". Psychological Science. 27 (6): 894–903. doi:10.1177/0956797616640705. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 27142460.

- ↑ Browning, Edgar K (1999). Microeconomic Theory & Applications 6th Edition. New York: Addison Wesley Educational Publishers.