Substance use disorder

| Substance use disorder | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | psychiatry |

| ICD-10 | F10-F19 |

| ICD-9-CM | 303-305 |

| MeSH | D019966 |

Substance use disorder (SUD), also known as drug use disorder, is a condition in which the use of one or more substances leads to a clinically significant impairment or distress.[1] Although the term substance can refer to any physical matter, 'substance' in this context is limited to psychoactive drugs.

SUD refers to the overuse of, or dependence on, a drug leading to effects that are detrimental to the individual's physical and mental health, or the welfare of others.[2] SUD is characterized by a pattern of continued pathological use of a medication, non-medically indicated drug or toxin, which results in repeated adverse social consequences related to drug use, such as failure to meet work, family, or school obligations, interpersonal conflicts, or legal problems.

There are on-going debates as to the exact distinctions between substance abuse and substance dependence, but current practice standard distinguishes between the two by defining substance dependence in terms of physiological and behavioral symptoms of substance use, and substance abuse in terms of the social consequences of substance use.[3] In the DSM-5 substance use disorder replaced substance abuse and substance dependence.[4][5][6]

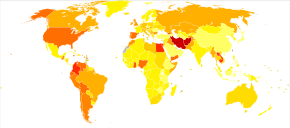

In 2013 drug use disorders resulted in 127,000 deaths; up from 53,000 in 1990.[7] The highest number of deaths are from opioid use disorders at 51,000.[7] Cocaine use disorder resulted in 4,300 deaths and amphetamine use disorder resulted in 3,800 deaths.[7] Alcohol use disorders resulted in an additional 139,000 deaths.[7]

Definitions

| Addiction and dependence glossary[8][9][10][11] |

|---|

| • addiction – a medical condition characterized by compulsive engagement in rewarding stimuli despite adverse consequences |

| • addictive behavior – a behavior that is both rewarding and reinforcing |

| • addictive drug – a drug that is both rewarding and reinforcing |

| • dependence – an adaptive state associated with a withdrawal syndrome upon cessation of repeated exposure to a stimulus (e.g., drug intake) |

| • drug sensitization or reverse tolerance – the escalating effect of a drug resulting from repeated administration at a given dose |

| • drug withdrawal – symptoms that occur upon cessation of repeated drug use |

| • physical dependence – dependence that involves persistent physical–somatic withdrawal symptoms (e.g., fatigue and delirium tremens) |

| • psychological dependence – dependence that involves emotional–motivational withdrawal symptoms (e.g., dysphoria and anhedonia) |

| • reinforcing stimuli – stimuli that increase the probability of repeating behaviors paired with them |

| • rewarding stimuli – stimuli that the brain interprets as intrinsically positive or as something to be approached |

| • sensitization – an amplified response to a stimulus resulting from repeated exposure to it |

| • substance use disorder - a condition in which the use of substances leads to clinically and functionally significant impairment or distress |

| • tolerance – the diminishing effect of a drug resulting from repeated administration at a given dose |

Substance abuse may lead to addiction or substance dependence. Medically, physiologic dependence requires the development of tolerance leading to withdrawal symptoms. Both abuse and dependence are distinct from addiction which involves a compulsion to continue using the substance despite the negative consequences, and may or may not involve chemical dependency. Dependence almost always implies abuse, but abuse frequently occurs without dependence, particularly when an individual first begins to abuse a substance. Dependence involves physiological processes while substance abuse reflects a complex interaction between the individual, the abused substance and society.[12]

Substance abuse is sometimes used as a synonym for drug abuse, drug addiction, and chemical dependency, but actually refers to the use of substances in a manner outside sociocultural conventions. All use of controlled drugs and all use of other drugs in a manner not dictated by convention (e.g. according to physician's orders or societal norms) is abuse according to this definition; however there is no universally accepted definition of substance abuse.

The physical harm for twenty drugs was compared in an article in the Lancet (see diagram, above right). Physical harm was assigned a value from 0 to 3 for acute harm, chronic harm and intravenous harm. Shown is the mean physical harm. Not shown, but also evaluated, was the social harm.

Substance use may be better understood as occurring on a spectrum from beneficial to problematic use. This conceptualization moves away from the ill-defined binary antonyms of "use" vs. "abuse" (see diagram, lower right) towards a more nuanced, public health-based understanding of substance use.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV TR) describes physical dependence, abuse of, and withdrawal from drugs and other substances. It does not use the word 'addiction' at all. It has instead a section about substance dependence:

"Substance dependence When an individual persists in use of alcohol or other drugs despite problems related to use of the substance, substance dependence may be diagnosed. Compulsive and repetitive use may result in tolerance to the effect of the drug and withdrawal symptoms when use is reduced or stopped. This, along with Substance Abuse are considered Substance Use Disorders..."[13]

Terminology has become quite complicated in the field. Pharmacologists continue to speak of addiction from a physiologic standpoint (some call this a physical dependence); psychiatrists refer to the disease state as psychological dependence; most other physicians refer to the disease as addiction. The field of psychiatry is now considering, as they move from DSM-IV to DSM-V, transitioning from "substance dependence" to "addiction" as terminology for the disease state.

Addiction is now narrowly defined as "uncontrolled, compulsive use"; if there is no harm being suffered by, or damage done to, the patient or another party, then clinically it may be considered compulsive, but to the definition of some it is not categorized as "addiction." In practice, the two kinds of addiction are not always easy to distinguish. Addictions often have both physical and psychological components.

There is also a lesser known situation called pseudo-addiction.[14] A patient will exhibit drug-seeking behavior reminiscent of addiction, but they tend to have genuine pain or other symptoms that have been under-treated. Unlike true addiction, these behaviors tend to stop when the pain is adequately treated.

Signs and symptoms

The medical community makes a distinction between physical dependence (characterized by symptoms of withdrawal) and psychological dependence (or simply addiction).

The DSM definition of addiction can be boiled down to compulsive use of a substance (or engagement in an activity) despite ongoing negative consequences—this is also a summary of what used to be called "psychological dependency." Physical dependence, on the other hand, is simply needing a substance to function. Humans are all physically dependent on oxygen, food and water. A drug can cause physical dependence and not addiction (for example, some blood pressure medications, which can produce fatal withdrawal symptoms if not tapered) and can cause addiction without physical dependence (the withdrawal symptoms associated with cocaine are all psychological, there is no associated vomiting or diarrhea as there is with opiate withdrawal).

There are several different screening tools that have been validated for use with adolescents such as the CRAFFT and adults such as the CAGE.

Physical dependency

Physical dependence on a substance is defined by the appearance of characteristic withdrawal symptoms when the substance is suddenly discontinued. Opiates, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, alcohol and nicotine induce physical dependence. On the other hand, some categories of substances share this property and are still not considered addictive: cortisone, beta blockers and most antidepressants are examples. So, while physical dependency can be a major factor in the psychology of addiction and most often becomes a primary motivator in the continuation of an addiction, the initial primary attribution of an addictive substance is usually its ability to induce pleasure, although with continued use the goal is not so much to induce pleasure as it is to relieve the anxiety caused by the absence of a given addictive substance, causing it to become used compulsively.

Some substances induce physical dependence or physiological tolerance - but not addiction — for example many laxatives, which are not psychoactive; nasal decongestants, which can cause rebound congestion if used for more than a few days in a row; and some antidepressants, most notably venlafaxine, paroxetine and sertraline, as they have quite short half-lives, so stopping them abruptly causes a more rapid change in the neurotransmitter balance in the brain than many other antidepressants. Many non-addictive prescription drugs should not be suddenly stopped, so a doctor should be consulted before abruptly discontinuing them.

The speed with which a given individual becomes addicted to various substances varies with the substance, the frequency of use, the means of ingestion, the intensity of pleasure or euphoria, and the individual's genetic and psychological susceptibility. Some people may exhibit alcoholic tendencies from the moment of first intoxication, while most people can drink socially without ever becoming addicted. Opioid dependent individuals have different responses to even low doses of opioids than the majority of people, although this may be due to a variety of other factors, as opioid use heavily stimulates pleasure-inducing neurotransmitters in the brain. Nonetheless, because of these variations, in addition to the adoption and twin studies that have been well replicated, much of the medical community is satisfied that addiction is in part genetically moderated. That is, one's genetic makeup may regulate how susceptible one is to a substance and how easily one may become psychologically attached to a pleasurable routine.

Eating disorders are complicated pathological mental illnesses and thus are not the same as addictions described in this article. Eating disorders, which some argue are not addictions at all, are driven by a multitude of factors, most of which are highly different from the factors behind addictions described in this article. It has been reported, however, that patients with eating disorders can successfully be treated with the same non-pharmacological protocols used in patients with chemical addiction disorders.[15] Gambling is another potentially addictive behavior with some biological overlap. Conversely gambling urges have emerged with the administration of Mirapex (pramipexole), a dopamine agonist.[16]

The obsolete term physical addiction is deprecated, because of its connotations. In modern pain management with opioids physical dependence is nearly universal. High-quality, long-term studies are needed to better delineate the risks and benefits of chronic opiate use.

Psychological dependency

In the now outdated conceptualization of the problem, psychological dependency leads to psychological withdrawal symptoms (such as cravings, irritability, insomnia, depression, anorexia, etc.). Addiction can in theory be derived from any rewarding behaviour, and is believed to be strongly associated with the dopaminergic system of the brain's reward system (as in the case of cocaine and amphetamines). Some claim that it is a habitual means to avoid undesired activity, but typically it is only so to a clinical level in individuals who have emotional, social, or psychological dysfunctions (psychological addiction is defined as such), replacing normal positive stimuli not otherwise attained.

A person who is physically dependent, but not psychologically dependent can have their dose slowly dropped until they are no longer physically dependent. However, if that person is psychologically dependent, they are still at serious risk for relapse into abuse and subsequent physical dependence.

Psychological dependence does not have to be limited only to substances; even activities and behavioural patterns can be considered addictions, if they become uncontrollable, e.g.problem gambling, Internet addiction, computer addiction, sexual addiction / pornography addiction, overeating, self-injury, compulsive buying, or work addiction.

Causes

Risk factors

As demonstrated by the chart below, numerous studies have examined factors which mediate substance abuse or dependence. In these examples, the predictor variables lead to the mediator which in turn leads to the outcome, which is always substance abuse or dependence. For example, research has found that being raised in a single-parent home can lead to increased exposure to stress and that increased exposure to stress, not being raised in a single-parent home, leads to substance abuse or dependence.[17] The following are some, but by no means all, of the possible mediators of substance abuse.

| Predictor Variables | Mediator Variables | Outcome Variable |

|---|---|---|

| Single-parent Home[17] | Exposure to Stress, Association w/ Deviant Peers | Substance Abuse or Dependence |

| Child Abuse/Neglect[18] | PTSD symptoms, Stressful Life Events, Criminal Behavior | Substance Abuse or Dependence |

| Parental Substance Abuse[19]

Witnessing Violence |

Physical/Sexual Abuse

Delinquency Status |

Substance Abuse or Dependence |

As demonstrated by the chart below, numerous studies have examined factors which moderate substance abuse or dependence. In these examples, the moderator variable impacts the level to which the strength of the relationship varies between a given predictor variable and the outcome of substance abuse or dependence. For example, there is a significant relationship between psychobehavioral risk factors, such as tolerance of deviance, rebelliousness, achievement, perceived drug risk, familism, family church attendance and other factors, and substance abuse and dependence. That relationship is moderated by familism which means that the strength of the relationship is increased or decreased based on the level of familism present in a given individual.[20]

| Predictor Variables | Moderator Variables | Outcome Variable |

|---|---|---|

| Psychobehavioral Risk[20] | Familism

Family Church Attendance |

Substance Abuse or Dependence |

| Victimization Effects[19] | Race/Ethnicity

Physical/Sexual Abuse |

Substance Abuse or Dependence |

| Family History of Alcoholism[21] | Gender | Substance Abuse or Dependence |

Examples of mediators and moderators can be found in several empirical studies. For example, Pilgrim et al.’s hypothesized mediation model posited that school success and time spent with friends mediated the relationship between parental involvement and risk-taking behavior with substance use (2006).[22] More specifically, the relationship between parental involvement and risk-taking behavior is explained via the interaction with third variables, school success and time spent with friends. In this example, increased parental involvement led to increased school success and decreased time with friends, both of which were associated with decreased drug use. Another example of mediation involved risk-taking behaviors. As risk-taking behaviors increased, school success decreased and time with friends increased, both of which were associated with increased drug use. A second example of a mediating variable is depression. In a study by Lo and Cheng (2007),[23] depression was found to mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and subsequent substance abuse in adulthood. In other words, childhood physical abuse is associated with increased depression, which in turn, in associated with increased drug and alcohol use in young adulthood. More specifically, depression helps to explain how childhood abuse is related to subsequent substance abuse in young adulthood.

A third example of a mediating variable is an increase of externalizing symptoms. King and Chassin (2008)[24] conducted research examining the relationship between stressful life events and drug dependence in young adulthood. Their findings identified problematic externalizing behavior on subsequent substance dependency. In other words, stressful life events are associated with externalizing symptoms, such as aggression or hostility, which can lead to peer alienation or acceptance by socially deviant peers, which could lead to increased drug use. The relationship between stressful life events and subsequent drug dependence however exists via the presence of the mediation effects of externalizing behaviors.

An example of a moderating variable is level of cognitive distortion. An individual with high levels of cognitive distortion might react adversely to potentially innocuous events, and may have increased difficulty reacting to them in an adaptive manner (Shoal & Giancola, 2005).[25] In their study, Shoal and Giancola investigated the moderating effects of cognitive distortion on adolescent substance use. Individuals with low levels of cognitive distortion may be more apt to choose more adaptive methods of coping with social problems, thereby potentially reducing the risk of drug use. Individuals with high levels of cognitive distortions, because of their increased misperceptions and misattributions, are at increased risk for social difficulties. Individuals may be more likely to react aggressively or inappropriately, potentially alienating themselves from their peers, thereby putting them at greater risk for delinquent behaviors, including substance use and abuse. In this study, social problems are a significant risk factor for drug use when moderated by high levels of cognitive distortions.

Mechanism

ΔFosB, a gene transcription factor, has been identified as playing a critical role in the development of addictive states in both behavioral addictions and drug addictions.[26][27][28] Overexpression of ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens is necessary and sufficient for many of the neural adaptations seen in drug addiction;[26] it has been implicated in addictions to alcohol, cannabinoids, cocaine, nicotine, phenylcyclidine, and substituted amphetamines[26][29][30][31] as well as addictions to natural rewards such as sex, exercise, and food.[27][28] A recent study also demonstrated a cross-sensitization between drug reward (amphetamine) and a natural reward (sex) that was mediated by ΔFosB.[32]

Management

Addiction severity index

Some medical systems, including those of at least 15 states of the United States, refer to an Addiction Severity Index[33] to assess the severity of problems related to substance use. The index assesses problems in six areas: medical, employment/support, alcohol and other drug use, legal, family/social, and psychiatric.

Detoxification

Early treatment of acute withdrawal often includes medical detoxification, which can include doses of anxiolytics or narcotics to reduce symptoms of withdrawal. An experimental drug, ibogaine,[34] is also proposed to treat withdrawal and craving.

Neurofeedback therapy has shown statistically significant improvements in numerous researches conducted on alcoholic as well as mixed substance abuse population. In chronic opiate addiction, a surrogate drug such as methadone is sometimes offered as a form of opiate replacement therapy. But treatment approaches universal focus on the individual's ultimate choice to pursue an alternate course of action.

Tailoring treatment

Therapists often classify patients with chemical dependencies as either interested or not interested in changing.

Treatments usually involve planning for specific ways to avoid the addictive stimulus, and therapeutic interventions intended to help a client learn healthier ways to find satisfaction. Clinical leaders in recent years have attempted to tailor intervention approaches to specific influences that affect addictive behavior, using therapeutic interviews in an effort to discover factors that led a person to embrace unhealthy, addictive sources of pleasure or relief from pain.

| Treatments | ||

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral pattern | Intervention | Goals |

| Low self-esteem, anxiety, verbal hostility | Relationship therapy, client centered approach | Increase self-esteem, reduce hostility and anxiety |

| Defective personal constructs, ignorance of interpersonal means | Cognitive restructuring including directive and group therapies | Insight |

| Focal anxiety such as fear of crowds | Desensitization | Change response to same cue |

| Undesirable behaviors, lacking appropriate behaviors | Aversive conditioning, operant conditioning, counter conditioning | Eliminate or replace behavior |

| Lack of information | Provide information | Have client act on information |

| Difficult social circumstances | Organizational intervention, environmental manipulation, family counseling | Remove cause of social difficulty |

| Poor social performance, rigid interpersonal behavior | Sensitivity training, communication training, group therapy | Increase interpersonal repertoire, desensitization to group functioning |

| Grossly bizarre behavior | Medical referral | Protect from society, prepare for further treatment |

| Adapted from: Essentials of Clinical Dependency Counseling, Aspen Publishers | ||

From the applied behavior analysis literature and the behavioral psychology literature, several evidenced-based intervention programs have emerged (1) behavioral marital therapy (2) community reinforcement approach (3) cue exposure therapy and (4) contingency management strategies.[35][36] In addition, the same author suggests that social skills training adjunctive to inpatient treatment of alcohol dependence is probably efficacious.

Epidemiology

In 2013 drug use disorders resulted in 127,000 deaths up from 53,000 in 1990.[7] The highest number of deaths are from opioid use disorders at 51,000.[7] Alcohol use disorders resulted in an addition 139,000 deaths.[7]

About 10.6% of Americans with substance use disorder seek treatment, and 40-60% of those people relapse within a year.[37]

Legality

Most countries have legislation which brings various drugs and drug-like substances under the control of licensing systems. Typically this legislation covers any or all of the opiates, substituted amphetamines, cannabinoids, cocaine, barbiturates, hallucinogens (tryptamines, LSD, phencyclidine, and psilocybin) and a variety of more modern synthetic drugs, and unlicensed production, supply or possession may be a criminal offense.

Usually, however, drug classification under such legislation is not related simply to addictiveness. The substances covered often have very different addictive properties. Some are highly prone to cause physical dependency, whilst others rarely cause any form of compulsive need whatsoever.

Also, although the legislation may be justifiable on moral grounds to some, it can make addiction or dependency a much more serious issue for the individual. Reliable supplies of a drug become difficult to secure as illegally produced substances may have contaminants. Withdrawal from the substances or associated contaminants can cause additional health issues and the individual becomes vulnerable to both criminal abuse and legal punishment. Criminal elements that can be involved in the profitable trade of such substances can also cause physical harm to users.

Opposition to common views

Thomas Szasz denies that addiction is a psychiatric problem. In many of his works, he argues that addiction is a choice, and that a drug addict is one who simply prefers a socially taboo substance rather than, say, a low risk lifestyle. In Our Right to Drugs, Szasz cites the biography of Malcolm X to corroborate his economic views towards addiction: Malcolm claimed that quitting cigarettes was harder than shaking his heroin addiction. Szasz postulates that humans always have a choice, and it is foolish to call someone an "addict" just because they prefer a drug induced euphoria to a more popular and socially welcome lifestyle.

Professor John Booth Davies at the University of Strathclyde has argued in his book The Myth of Addiction that "people take drugs because they want to and because it makes sense for them to do so given the choices available" as opposed to the view that "they are compelled to by the pharmacology of the drugs they take."[38] He uses an adaptation of attribution theory (what he calls the theory of functional attributions) to argue that the statement "I am addicted to drugs" is functional, rather than veridical. Stanton Peele has put forward similar views.

See also

References

- ↑ "NAMI Comments on the APA's Dr aft Revision of the DSM-V Substance Use Disorders" (PDF). National Alliance on Mental Illness. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ↑ (1998). Mosby's Medical, Nursing & Allied Health Dictionary. Edition 5.

- ↑ Pham-Kanter, Genevieve. (2001). "Substance abuse and dependence." The Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Second Edition. Jacqueline L. Longe, Ed. 5 vols. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group.

- ↑ "Substance use disorders" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ "Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders" (PDF). American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ↑ Association, American Psychiatric; others (2013). DSM 5. American Psychiatric Association.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.". Lancet. 385: 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604

. PMID 25530442.

. PMID 25530442. - ↑ Nestler EJ (December 2013). "Cellular basis of memory for addiction". Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 15 (4): 431–443. PMC 3898681

. PMID 24459410.

. PMID 24459410. - ↑ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY. Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 364–375. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ↑ "Glossary of Terms". Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Department of Neuroscience. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT (January 2016). "Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction". N. Engl. J. Med. 374 (4): 363–371. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1511480. PMID 26816013.

- ↑

- ↑ DSM-IV & DSM-IV-TR:Substance Dependence

- ↑ Weissman, D.E.; J.D. Haddox (1989). "Opioid pseudoaddiction--an iatrogenic syndrome". Pain. International Association for the Study of Pain. 36 (3): 363–366. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(89)90097-3. PMID 2710565.

- ↑ AJ Giannini, M Keller, GC Colapietro, SM Melemis, N Leskovac, T Timcisko. Comparison of alternative treatment techniques in bulimia: The chemical dependency approach. Psychological Reports. 82(2):451-458, 1998.

- ↑ AJ Giannini. Drugs of Abuse--Second Edition. Los Angeles, Practice Management Information Corporation, 1997.

- 1 2 Barrett AE, Turner RJ (January 2006). "Family structure and substance use problems in adolescence and early adulthood: examining explanations for the relationship". Addiction. 101 (1): 109–20. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01296.x. PMID 16393197.

- ↑ White HR, Widom CS (May 2008). "Three potential mediators of the effects of child abuse and neglect on adulthood substance use among women". J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 69 (3): 337–47. PMID 18432375.

- 1 2 Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Saunders B, Resnick HS, Best CL, Schnurr PP (February 2000). "Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: data from a national sample". J Consult Clin Psychol. 68 (1): 19–30. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.68.1.19. PMID 10710837.

- 1 2 Brook JS, Pahl K (September 2005). "The protective role of ethnic and racial identity and aspects of an Africentric orientation against drug use among African American young adults". J Genet Psychol. 166 (3): 329–45. doi:10.3200/GNTP.166.3.329-345. PMC 1315285

. PMID 16173675.

. PMID 16173675. - ↑ Ohannessian, C.M., Hasselbrock, V.M. (1999). Predictors of substance abuse and affective diagnosis: Does having a family history of alcoholism make a difference?. Applied Developmental Science, 3, 239-247.

- ↑ Pilgrim CC, Schulenberg JE, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD (March 2006). "Mediators and moderators of parental involvement on substance use: a national study of adolescents". Prev Sci. 7 (1): 75–89. doi:10.1007/s11121-005-0019-9. PMID 16572302.

- ↑ Lo CC, Cheng TC (2007). "The impact of childhood maltreatment on young adults' substance abuse". Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 33 (1): 139–46. doi:10.1080/00952990601091119. PMID 17366254.

- ↑ King KM, Chassin L (September 2008). "Adolescent stressors, psychopathology, and young adult substance dependence: a prospective study". J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 69 (5): 629–38. PMC 2575393

. PMID 18781237.

. PMID 18781237. - ↑ Shoal GD, Giancola PR (November 2005). "The relation between social problems and substance use in adolescent boys: an investigation of potential moderators". Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 13 (4): 357–66. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.13.4.357. PMID 16366766.

- 1 2 3 Robison AJ, Nestler EJ (November 2011). "Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction". Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12 (11): 623–637. doi:10.1038/nrn3111. PMC 3272277

. PMID 21989194.

. PMID 21989194. ΔFosB has been linked directly to several addiction-related behaviors ... Importantly, genetic or viral overexpression of ΔJunD, a dominant negative mutant of JunD which antagonizes ΔFosB- and other AP-1-mediated transcriptional activity, in the NAc or OFC blocks these key effects of drug exposure14,22–24. This indicates that ΔFosB is both necessary and sufficient for many of the changes wrought in the brain by chronic drug exposure. ΔFosB is also induced in D1-type NAc MSNs by chronic consumption of several natural rewards, including sucrose, high fat food, sex, wheel running, where it promotes that consumption14,26–30. This implicates ΔFosB in the regulation of natural rewards under normal conditions and perhaps during pathological addictive-like states.

- 1 2 Blum K, Werner T, Carnes S, Carnes P, Bowirrat A, Giordano J, Oscar-Berman M, Gold M (2012). "Sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll: hypothesizing common mesolimbic activation as a function of reward gene polymorphisms". J. Psychoactive Drugs. 44 (1): 38–55. doi:10.1080/02791072.2012.662112. PMC 4040958

. PMID 22641964.

. PMID 22641964. It has been found that deltaFosB gene in the NAc is critical for reinforcing effects of sexual reward. Pitchers and colleagues (2010) reported that sexual experience was shown to cause DeltaFosB accumulation in several limbic brain regions including the NAc, medial pre-frontal cortex, VTA, caudate, and putamen, but not the medial preoptic nucleus. Next, the induction of c-Fos, a downstream (repressed) target of DeltaFosB, was measured in sexually experienced and naive animals. The number of mating-induced c-Fos-IR cells was significantly decreased in sexually experienced animals compared to sexually naive controls. Finally, DeltaFosB levels and its activity in the NAc were manipulated using viral-mediated gene transfer to study its potential role in mediating sexual experience and experience-induced facilitation of sexual performance. Animals with DeltaFosB overexpression displayed enhanced facilitation of sexual performance with sexual experience relative to controls. In contrast, the expression of DeltaJunD, a dominant-negative binding partner of DeltaFosB, attenuated sexual experience-induced facilitation of sexual performance, and stunted long-term maintenance of facilitation compared to DeltaFosB overexpressing group. Together, these findings support a critical role for DeltaFosB expression in the NAc in the reinforcing effects of sexual behavior and sexual experience-induced facilitation of sexual performance. ... both drug addiction and sexual addiction represent pathological forms of neuroplasticity along with the emergence of aberrant behaviors involving a cascade of neurochemical changes mainly in the brain's rewarding circuitry.

- 1 2 Olsen CM (December 2011). "Natural rewards, neuroplasticity, and non-drug addictions". Neuropharmacology. 61 (7): 1109–22. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.010. PMC 3139704

. PMID 21459101.

. PMID 21459101. - ↑ Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ (2006). "Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory". Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 29: 565–598. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113009. PMID 16776597.

- ↑ Steiner H, Van Waes V (January 2013). "Addiction-related gene regulation: risks of exposure to cognitive enhancers vs. other psychostimulants". Prog. Neurobiol. 100: 60–80. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.10.001. PMC 3525776

. PMID 23085425.

. PMID 23085425. - ↑ Kanehisa Laboratories (2 August 2013). "Alcoholism – Homo sapiens (human)". KEGG Pathway. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ↑ Pitchers KK, Vialou V, Nestler EJ, Laviolette SR, Lehman MN, Coolen LM (February 2013). "Natural and drug rewards act on common neural plasticity mechanisms with ΔFosB as a key mediator". J. Neurosci. 33 (8): 3434–42. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4881-12.2013. PMC 3865508

. PMID 23426671.

. PMID 23426671. Together, these findings demonstrate that drugs of abuse and natural reward behaviors act on common molecular and cellular mechanisms of plasticity that control vulnerability to drug addiction, and that this increased vulnerability is mediated by ΔFosB and its downstream transcriptional targets.

- ↑ Butler SF, Budman SH, Goldman RJ, Newman FL, Beckley KE, Trottier D. Initial Validation of a Computer-Administered Addiction Severity Index: The ASI-MV Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 2001 March

- ↑ Alper KR, Lotsof HS, Kaplan CD (January 2008). "The ibogaine medical subculture". J Ethnopharmacol. 115 (1): 9–24. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2007.08.034. PMID 18029124.

- ↑ O'Donohue, W; K.E. Ferguson (2006). "Evidence-Based Practice in Psychology and Behavior Analysis". The Behavior Analyst Today. Joseph D. Cautilli. 7 (3): 335–350. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ↑ Chambless, D.L.; et al. (1998). "An update on empirically validated therapies" (PDF). Clinical Psychology. American Psychological Association. 49: 5–14. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ↑ McLellan, A. T.; Lewis, D. C.; O'Brien, C. P.; Kleber, H. D. (2000-10-04). "Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation". JAMA. 284 (13): 1689–1695. doi:10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 11015800.

- ↑ Davies, John Booth (1998-01-18). The Myth of Addiction. Psychology Press Ltd (2nd rev edition). ISBN 978-90-5702-237-1.