Stuart Little

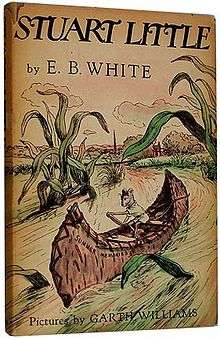

First edition | |

| Author | E. B. White |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Garth Williams |

| Cover artist | Garth Williams |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Children's novel |

| Publisher | Harper & Brothers |

Publication date | 1945 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 128 |

| Followed by | Charlotte's Web |

Stuart Little is a 1945 children's novel by E. B. White,[1] his first book for children, and is widely recognized as a classic in children's literature. Stuart Little was illustrated by the subsequently award-winning artist Garth Williams, also his first work for children. It is a realistic fantasy about Stuart Little who, though born to human parents in New York City, ″looked very much like a mouse in every way″ (chapter I).

Background

In a letter White wrote in response to inquiries from readers, he described how he came to conceive of Stuart Little: "many years ago I went to bed one night in a railway sleeping car, and during the night I dreamed about a tiny boy who acted rather like a mouse. That's how the story of Stuart Little got started".[2] He had the dream in the spring of 1926, while sleeping on a train on his way back to New York from a visit to the Shenandoah Valley.[3] Biographer Michael Sims wrote that Stuart "arrived in [White's] mind in a direct shipment from the subconscious."[3] White typed up a few stories about Stuart, which he told to his 18 nieces and nephews when they asked him to tell them a story. In 1935, White's wife Katharine showed these stories to Clarence Day, then a regular contributor to The New Yorker. Day liked the stories and encouraged White not to neglect them, but neither Oxford University Press nor Viking Press was interested in the stories,[4] and White did not immediately develop them further.[5]

In the fall of 1938, as his wife wrote her annual collection of children's book reviews for The New Yorker, White wrote a few paragraphs in his "One Man's Meat" column in Harper's Magazine about writing children's books.[4] Anne Carroll Moore, the head children's librarian at the New York Public Library, read this column and responded by encouraging him to write a children's book that would "make the library lions roar".[4] White's editor at Harper, who had heard about the Stuart stories from Katherine, asked to see them, and by March 1939 was intent on publishing them. Around that time, White wrote to James Thurber that he was "about half done" with the book; however, he made little progress with it until the winter of 1944-1945.[6]

Plot

First we learn of Stuart's birth to a family in New York City and how the family adapts, socially and structurally, to having such a small son. He has an adventure in which he also gets caught in a window-blind while exercising; Snowbell, the family cat, then places Stuart's hat and cane outside a mouse hole, panicking the family. He was accidentally released by his brother George. Then two chapters describe Stuart's participation in a model sailboat race in Central Park. A bird named Margalo is adopted by the Little family, and Stuart protects her from Snowbell, their malevolent cat. The bird repays her kindness by saving Stuart when he is trapped in a garbage can and shipped out for disposal at sea.

Margalo flees when she is warned that one of Snowbell's friends intends to eat her, and Stuart strikes out to find her. A friendly dentist, who is also the owner of the boat Stuart had raced in Central Park, gives him use of a gasoline-powered model car, and Stuart departs to see the country. He works for a while as a substitute teacher and comes to the town of Ames Crossing, where he meets a girl named Harriet Ames who is no taller than he is. They go on one date, but it doesn't work because the boat was found broken. As the book ends, he has not yet found Margalo, but feels confident he will do so.

Reception

Lucien Agosta, in his overview of the critical reception of the book, notes that "Critical reactions to Stuart Little have varied from disapprobation to unqualified admiration since the book was published in 1945, though generally it has been well received."[7] Anne Carroll Moore, who had initially encouraged White to write the book, was critical of it when she read a proof of it.[8] She wrote letters to White; his wife, Katharine; and Ursula Nordstrom, the children's editors at Harper's, advising that the book not be published.[8]

Malcolm Cowley, who reviewed the book for The New York Times, wrote, "Mr. White has a tendency to write amusing scenes instead of telling a story. To say that Stuart Little is one of the best children's books published this year is very modest praise for a writer of his talent."[9] The book has become a children's classic, and is widely read by children and used by teachers.[10] White received the Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal in 1970 for Stuart Little and Charlotte's Web.[11]

Adaptations

Film

The book was very loosely adapted into a 1999 film of the same name, which combined live-action with computer animation. A 2002 sequel to the first film, Stuart Little 2, was truer to the book. A third film, Stuart Little 3: Call of the Wild was released direct-to-video in 2006. This film was entirely computer-animated, and its plot was not derived from the book. All three films feature Hugh Laurie as Mr. Little, Geena Davis as Mrs. Little, and Michael J. Fox as the voice of Stuart Little.

Television

"The World of Stuart Little," a 1966 episode of NBC's Children's Theater, narrated by Johnny Carson, won a Peabody Award and was nominated for an Emmy. An animated television series, Stuart Little: The Animated Series, (based on the film adaptations) was produced for HBO Family and aired for 13 episodes in 2003.

Video games

Three video games based on Stuart Little were produced, but were mostly based off the film adaptations of the same name. Stuart Little: the Journey Home based on the 1999 film, was released only for the Game Boy Color in 2001. A game based on Stuart Little 2 was released for the PlayStation, Game Boy Advance and Microsoft Windows in 2002. And a third game entitled Stuart Little 3: Big Photo Adventure was released exclusively for the PlayStation 2 in 2005. Although it bears no resembleance to the film Stuart Little 3: Call of the Wild.

Notes

- ↑ Adrian Hennigan (1 November 2001). "Kids' Stuff". BBC. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ↑ "Author Essay by E. B. White from HarperCollins Publishers". Harpercollins.com. 2010-03-24. Retrieved 2012-07-14.

- 1 2 Sims 2011, p. 145

- 1 2 3 Elledge (1986), p. 254

- ↑ Sims 2011, p. 146

- ↑ Elledge (1986), p. 255

- ↑ Agosta 1995, p. 59

- 1 2 Elledge 1986, p. 263-264

- ↑ Cowley, Malcolm (28 October 1945). "Stuart Little: Or New York Through the Eyes of a Mouse". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ↑ A Guide for Using Stuart Little in the Classroom, Lorraine Kujawa and Virginia Wiseman, Teacher Created Resources 2004, ISBN 978-1-57690-628-6

- ↑ "About E.B. White". Harper Collins. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

References

- Agosta, Lucien (1995). E.B. White: The Children's Books. New York City: Twayne Publishers.

- Elledge, Scott (1986). E.B. White: A biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-30305-5.

- Sims, Michael (2011). The Story of Charlotte's Web. New York: Walker Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8027-7754-6.

External links

- Stuart Little first edition dustjacket at NYPL Digital Gallery