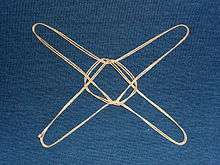

String figure

A string figure (Inuktitut: Ajaraarutit[1]) is a design formed by manipulating string on, around, and using one's fingers or sometimes between the fingers of multiple people. String figures may also involve the use of the mouth, wrist, and feet. They may consist of singular images or be created and altered as a game, known as a string game, or as part of a story involving various figures made in sequence (string story). String figures have also been used for divination, such as to predict the sex of an unborn child.[2]

The most popular and well-known string game appears to be cat's cradle. According to Jayne, a trick known as "The Mouse" is, "probably the most widely distributed of all the string figures," known to Murray Island, Germany, Inuit, N. & S. America, Japan, Philippines, Australia, Batwa, Negrito, Linao Moros, Chippewa, Osage, Navajo, Apache, Omaha, Japanese, Torres Straits, Irish, Wajiji, and Alaskan Inuit people.[3] String figures, which are well distributed throughout the world,[4] include "Jacob's Ladder" ("Osage Diamonds", "Fishnet"), "Cup and Saucer" ("Sake Glass", "Coffee Cup"), and "Tree Hole"[5] ("The Moon Gone Dark", "Sun",[5] "Moon"[5]).

History

According to Camilla Gryski, a Canadian librarian and author of numerous string figure books, "We don't know when people first started playing with string, or which primitive people invented this ancient art. We do know that all primitive societies had and used string—for hunting, fishing, and weaving—and that string figures have been collected from native peoples all over the world."[6]

"Of the games people play, string figures enjoy the reputation of being the most widespread form of amusement in the world: more cultures are familiar with string figures than with any other game. Over 2,000 individual patterns have been recorded worldwide since 1888, when anthropologist Franz Boas first described a pair of Eskimo string figures (Boas 1888a, 1888b, Abraham 1988:12)."[7] String figures are probably one of humanity's oldest games, and is spread among an astonishing variety of cultures, even ones as unrelated as Europeans and the Dayaks of Indonesia; Alfred Wallace who, while traveling in Borneo in the 1800s, thought of amusing the Dayak youths with a novel game with string, was in turn very surprised when they proved to be familiar with it, and showed him some figures and transitions that he hadn't previously seen.[8][9] The anthropologist Louis Leakey has also attributed string figure knowledge with saving his life[10] and described his use of this game in the early 1900s to obtain the cooperation of Sub-Saharan African tribes otherwise unfamiliar with, and suspicious of, Europeans,[8] having been told by his teacher A.C. Haddon, "You can travel anywhere with a smile and a piece of string."[10]

The Greek physician Heraklas produced the earliest known written description of a string figure in his first century monograph on surgical knots and slings.[11][12][13] This work was preserved by republication in Oribasius' fourth century Medical Collections. The figure is described as a sling to set and bind a broken jaw, with the chin being placed in the center of the figure and the four loops tied near the top of the head. Called the "Plinthios Brokhos", the resulting figure has been identified by multiple sources as the figure known to Aboriginal Australians as "The Sun Clouded Over".[14] The Inuit are purported to possess a string figure representing the extinct woolly mammoth.[15]

String figures were widely studied by anthropologists like James Hornell[17] from the 1880s through around 1900, as they were used in attempts to trace the origin and developments of cultures. String figures, once thought to have proven monogenesis, appear to have arisen independently as an entertainment pastime in many societies. Many figures were collected and described from south-east Asia, Japan, South America, West Indies, Pacific Islanders, Inuit and other Native Americans.[6] Figures have also been collected in Europe and Africa. One of the major works on the subject is String Figures and How to Make Them (DjVu), by Caroline Furness Jayne.

The International String Figure Association (ISFA) was formed in 1978 with the primary goal of gathering, preserving, and distributing string figure knowledge so that future generations will continue to enjoy this ancient pastime.[18]

Terms

In string figure literature there are many phrases often used, however there may be some variation with the fingers, loops, and strings indicated in different ways. A loop is the strings that go around the back of a finger, multiple fingers, or another body part such as the wrist. Some authors name the strings, fingers and their loops (near middle finger string, right index finger, pinky loop, for example), while others number them (3n, R1, 5 loop). One of the first methods of recording figures and sets of terminology was an anatomical system proposed in "A Method of Recording String Figures and Tricks" by W. H. R. Rivers and A. C. Haddon.[20] Though location or locations of a string are most often indicated by casual systems of terms such as "near" or "far", the Rivers and Haddon system is far less ambiguous, though this may be unnecessary for the most common, illustrated, figures.[21]

Below are some common moves, openings, and extensions.

- Openings

- Murray Opening/Index Opening: The loop is grasped with the middle, ring, and little fingers so that there is a couple inches of string between them. These fingers are put together so there is a circle made by the overlapping strings. The index finger is inserted from the far side into the circle, and the index finger rotated upwards, circling towards the body.

- Position 1: The untwisted loop is put on the thumb and little fingers.

- Opening A: Following from Position 1, the right index finger picks up the string on the left hand going between the thumb and the little finger. The left index finger then goes between both strings of right index finger, and picks up the string going from the right thumb to little finger.

- Japanese Opening: The Japanese Opening is similar to Opening A, however the strings are picked up with the middle fingers instead of the index fingers.

- Extensions

- Caroline Extension: Starting with a loop on the thumb, the string is lifted in the nook of the index finger, then pinched between the index finger and thumb.

- Moves

- Pick up

- Navajo leap, "navajoing", or "Navajo": Given two loops on one finger, the lower loop is moved over the upper loop and released from the finger.

- Release

- Transfer

- Rotate

- Share

Notable collectors and enthusiasts

- Anthropologists & ethnologists

- Other

- Camilla Gryski (librarian)

- Kathleen Haddon (zoologist)

- Honor Maude (enthusiast)

- W. W. Rouse Ball (mathematician)

- Mark Sherman (biochemist)

- Harry Everett Smith (artist)

- Hiroshi Noguchi (Ayatori player)

See also

- Cat's cradle

- List of string figures

- Spider Grandmother

- Diné Bahaneʼ#Spider Man, Spider Woman and Weaving

References

- ↑ Jean Malaurie (2000) (in German), [, p. 181, at Google Books Mythos Nordpol. 200 Jahre Expeditionsgeschichte], National Geographic, pp. 181, ISBN 3-936559-20-1, , p. 181, at Google Books

- ↑ Foster Jr., George M. (1941). "String-Figure Divination". American Anthropologist, New Series. 43 (1): 126–127. doi:10.1525/aa.1941.43.1.02a00300.

- ↑ Jayne (1962), p.340. Also Elffers & Schuyt (1979), p.44-5.

- ↑ Lois & Earl W. Stokes. "The Ancient Art of Hawaiian String Figures". Web of Life International, a project of Aloha International.

- 1 2 3 Elffers, Joost and Schuyt, Michael (1978/1979). Cat's Cradles and Other String Figures, p.197. ISBN 0-14-005201-1.

- 1 2 Gryski, Camilla (1983). Cat's Cradle, Owl's Eyes: A Book of String Games, p.4. ISBN 0-688-03941-3.

- ↑ Averkieva, Julia P. and Sherman, Mark A. (1992). "Introduction by Mark A. Sherman", Kwakiutl String Figures, p.xiii. University of British Columbia. ISBN 978-0-7748-0432-5.

- 1 2 Buchanan, Andrea J. and Peskowitz, Miriam (2007). The Daring Book for Girls, p.277. ISBN 978-0-06-147257-2.

- ↑ Wallace, Alfred (1872). The Malay Archipelago, Volume 1, p.89. Macmillan.

- 1 2 Morell, Virginia (1996). Ancestral Passions, p.33. ISBN 978-0-684-82470-3.

- ↑ Miller, Lawrence G. (1945). "The Earliest (?) Description of a String Figure". American Anthropologist, New Series. 47 (3): 461–462. doi:10.1525/aa.1945.47.3.02a00190.

- ↑ D'Antoni, Joseph (1997), Bulletin of the International String Figure Association, 4, pp. 90–94, ISSN 1076-7886

- ↑ ISFA (June 2001). "Plinthios Brokhos". String Figure Magazine. International String Figure Association. 6 (2): 3–4. Retrieved 2008-08-13.

- ↑ Day, Cyrus L. (1967). Quipus and Witches' Knots. Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Press. pp. 86–89, 124–126.

- ↑ T. T. Paterson (1949), "Eskimo String Figures and Their Origin," Acta Arctica 3:1-98.

- ↑ Knight, C. (1995). Blood Relations: Menstruation and the Origins of Culture. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 445. Figure re-drawn after McCarthy, F. D. (1960). "The string figures of Yirrkalla". In Mountford, C. P. Records of the American-Australian Scientific Expedition in Arnhem Land. Anthropology and Nutrition. 2. Melbourne University Press. pp. 415–513 [466].

- ↑ Heppell, David; Sherman, Mark (2000). "Abstract A Tribute to James Hornell (1865-1949)". Bulletin of the International String Figure Association (7). pp. 1–56.

- ↑ "About ISFA". 1999-06-26. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- ↑ Gryski (1983), p.18-9. ISBN 0590254863.

- ↑ "A Method of Recording String Figures and Tricks". W. H. R. Rivers; A. C. Haddon. Man, Vol. 2. (1902), pp. 146-153. Man is currently published by Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland.

- ↑ Averkieva and Sherman (1992), p.xxviii. ISBN 978-0-7748-0432-5.

Further reading

- Bulletin of the International String Figure Association, isfa.org

- Caroline Furness Jayne (1906), String Figures and How to Make Them, ISBN 0-486-20152-X

- An exhaustive study of this material culture

- Anne Akers Johnson, String Games from Around the World, Klutz 1996

- A book for beginners

- Kathleen Haddon, String Games for Beginners, Cambridge, UK: Heffer 1934 (many later editions)

- 28 figures, 40 pages

- Camilla Gryski, Cat's Cradle, Owl's Eyes, 1987, New York: William Morrow & Co Library

- A book for beginners

- Many stars and more string games, New York: William Morrow & Co Library 1985, ISBN 0-688-05792-6

- A book for beginners

- Super string games, New York: William Morrow & Co Library 1996, ISBN 0-688-15040-3

- A book for advanced

- Fascinating String Figures, International String Figure Association 1999, Dover, ISBN 0-486-40400-5

- Julia P. Averkieva with Mark A. Sherman (contributor), "Kwakiutl String Figures", in: Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of History, Vol. 71 (1992), Seattle: University of Washington Press, ISBN 0-7748-0432-7

- 199 pages

- Joost Elffers and Michael Schuyt, Cat's Cradles and Other String Figures, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books 1979. ISBN 0-14-005201-1 (Viking Press, 1980, paperback).

- 207 pages, a book for beginners and advanced, English translation of German, features photographs

- Anne Pellowski, Story Vine, New York: Macmillan Publishing Company 1984, ISBN 0-02-044690-X

- 116 pages - String stories

- Noble, Phillip. String figures of Papua New Guinea. Boroko, Papua New Guinea: Institute of Papua New Guinea Studies, 1979.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to String figures. |

- Official website of the International String Figure Association, based in Pasadena, CA.

- Collection of Favorite String Figures - Many examples with video clips showing how to make them.

- Magazines Ficelles, "String Magazines" with many figures in English.

- "The Survival, Origin and Mathematics of String Figures" by Martin Probert.

- Magazine Mai 2003, "[String Figures from the] Island of Moa", collected by Kathleen Haddon.

- How to Make a Cat's Cradle from a Piece of String: a video tutorial, MetaCafe.com.

- myriamn's Videos Some tutorial videos, YouTube.com.

- String Games.pdf by Arvind Gupta cs.sfu.ca, arvindguptatoys.com with illustrations by Avinash Deshpande (52-page PDF book).

- Jayne, C. F. (1962/2009). String Figures and How to Make Them - complete text and illustrations from the book, in HTML format. Jamis Buck, compiler.

- LOop Paper Toys A series of DEMO videos about String Figures made by Ludwig Caballero.

- Murphy, James R. (11/06/2012). "The Hands of Children Playing With String Will Lead Us Into the Future", HuffingtonPost.com.