Streptospondylus

| Streptospondylus Temporal range: Middle Jurassic, 161 Ma | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Streptospondylus altdorfensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | †Megalosauria |

| Genus: | †Streptospondylus von Meyer, 1832 |

| Species | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Streptospondylus (meaning "reversed vertebra") is a genus of tetanuran theropod dinosaur known from the Middle Jurassic period of France, 161 million years ago. It was a medium-sized predator.

Discovery and naming

Streptospondylus was one of the first dinosaurs collected and is the first described, though not named. From about 1770, a certain abbey Bachelet, an amateur naturalist living in Rouen, began to collect fossils. These included some theropod vertebrae and limb elements found near Honfleur. In 1776 abbey Jean-François Dicquemare working in Le Havre reported some similar bones, interpreted by him as the remains of dolphins and porpoises.[2] After the death of Bachelet his collection was taken over by C. Guersent, professor of natural history at Rouen. In 1799 the prefect of Seine-Inférieure, count Jacques Claude Beugnot, ordered to move it to the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris. In 1800 the collection was reported by Georges Cuvier who combined the material with that from the collection of Dicquemare, also obtained by the Paris museum.[3]

In 1808, Cuvier scientifically described the theropod vertebrae as the first dinosaur remains ever. However, he considered them to be crocodilian and associated them with fossils of the Teleosauridae and the Metriorhynchidae.[4] In 1822, Cuvier by the work of Henry De La Bèche became aware that these finds were very disparate, stemming from different periods. He abstained from naming them but in 1824 concluded that there were two main types. In 1825 Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire accordingly named two crocodilian skulls as the genus Steneosaurus, the one, specimen MNHN 8900, becoming Steneosaurus rostromajor, the other, MNHN 8902, S. rostrominor.[5]

In 1832 however, the German paleontologist Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer split the material. Steneosaurus rostrominor was renamed Metriorhynchus geoffroyii while Steneosaurus rostromajor became Streptospondylus altdorfensis. To the last species the theropod remains were referred.[6] The generic name is derived from Greek στρεπτος/streptos, "reversed", and σπονδυλος/spondylos, "vertebra", alluding to the fact that the vertebrae differed from typical crocodile elements in being opisthocoel: convex in front and concave behind. The specific name refers to Altdorf where also some teleosaurid remains had been found. Von Meyer's name was the first binomial name (also) referring to a theropod.

In 1842 Richard Owen pointed out that von Meyer had been incorrect in changing the original specific name and created the correct combination Streptospondylus rostromajor for Streptospondylus altdorfensis. At the same time he created a second species: Streptospondylus cuvieri based on a single damaged vertebra from the Bathonian, found near Chipping Norton.[7] In 1861, Owen would refer the entire Cuvier material to S. cuvieri, despite the fact that if it were cospecific the name S. rostromajor would have priority. From that time S. cuvieri was generally accepted in the literature as the valid name, though some workers split off the theropod remains from the crocodilian bones, Edward Drinker Cope in 1867 naming a Laelaps gallicus and Friedrich von Huene in 1909 a Megalosaurus cuvieri.

In 1964, Alick Donald Walker discovered Owen's mistake, referring the entire theropod material to the new species Eustreptospondylus divesensis which, however, had a skull not belonging to the Cuvier material as the type specimen, MNHN 1920-7.[8] In 1977 Philippe Taquet created the genus Piveteausaurus for this species.

In 2001, Ronan Allain concluded that no connection could be proven between Piveteausaurus and the referred other theropod material from Normandy. He also pointed out that the skull von Meyer had based Streptospondylus altdorfensis on was in fact a composite of bones from two species, since named Steneosaurus edwardsi Deslongchamps 1866 and Metriorynchus superciliosum Blainville 1853. Never a lectotype had been chosen from one of the composite parts to give the name Streptospondylus priority over either one of these species. Allain used this situation to remove all the crocodilian material from the Streptospondylus type by designating the complete theropod material as the lectotype. As Steneosaurus rostromajor had been based on the composite skull, the epithet rostromajor now no longer had priority over altdorfensis. This way in 2001 Streptospondylus altdorfensis became the valid name and type species of a theropod. Laelaps gallicus and Megalosaurus cuvieri are its objective junior synonyms.[1]

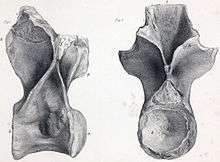

The lectotype specimens, MNHN 8605-09, 8787-89, 8793-94, 8907, were probably found at the coast in layers of the Falaises des Vaches Noires near Calvados, dating from the late Callovian or early Oxfordian, about 161 million years old. They consist of several vertebrae series, single vertebrae, a partial left pubis and limb elements. The longest vertebra has a length of 97 millimetres, indicating a total body length of about seven metres. Also a partial left femur, MNHN 9645, has been referred. Streptospondylus has been diagnosed by several osteological details, among which the possession of two hypapophyses on the, ventrally flat, anterior dorsal vertebrae and the particular connection between the astragalus and the tibia, without a posterior astragalar process but with a distinctive buttress on the tibia above the anterior process.

Owen also named two other species, S. major[7] (S. recentior is a museum label for syntype specimens [9]) and S. meyeri,[10] of which the former is based on iguanodont material. His S. cuvieri, of which the type specimen is lost, is today considered a nomen dubium.

In 2010 Gregory S. Paul renamed (as an informal name) Magnosaurus into Streptospondylus nethercombensis.[11]

Phylogeny

Earlier assigned to crocodilian groups, Streptospondylus was in the 20th century typically classified in the Megalosauridae.

Recent analyses indicate that Streptospondylus is a tetanuran theropod. Allain in 2001 suggested that it was closely related to Eustreptospondylus in the Spinosauroidea. Roger Benson in 2008 and 2010 concluded that whether it is a megalosauroid, allosauroid, or a more primitive form cannot be determined because of its extremely fragmentary remains.[12] Later cladistic analysis by Benson and colleagues from 2010 indicated that Streptospondylus was the sister species of Magnosaurus within the Megalosauridae.[13]

References

- 1 2 Allain R (2001). "Redescription de Streptospondylus altdorfensis, le dinosaure théropode de Cuvier, du Jurassique de Normandie [Redescription of Streptospondylus altdorfensis, Cuvier's theropod dinosaur from the Jurassic of Normandy]". Geodiversitas. 23 (3): 349–367.

- ↑ Dicquemare J.F. (1776). "Ostéollithes". Journal de Physique. VII: 406–414.

- ↑ Cuvier G (1800). "A quantity of bones found in the rocks in the environs of Honfleur, by the late Abbé Bachelet". Philosophical Magazine. VIII: 290.

- ↑ Cuvier G (1808). "Sur les ossements fossiles de crocodiles et particulièrement sur ceux des environs du Havre et d'Honfleur, avec des remarques sur les squelettes de sauriens de la Thuringe". Annales du Muséum d’Histoire naturelle de Paris. XII: 73–110.

- ↑ Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire E (1825). "Recherches sur l'organisation des gavials". Mémoires du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle. 12: 97–155.

- ↑ Meyer, H. von, 1832, Paleologica zur Geschichte der Erde, Frankfurt am Main, 560 p

- 1 2 Owen R (1842). "Report on British fossil reptiles". Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. 11: 60–204.

- ↑ Walker A.D. (1964). "Triassic reptiles from the Elgin area: Ornithosuchus and the origin of carnosarus". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 248: 53–134. Bibcode:1964RSPTB.248...53W. doi:10.1098/rstb.1964.0009.

- ↑ Mantell, G. A., 1851, Petrifactions and their teachings; or a hand-book to the Gallery of Organic remains of The British Museum, London, 496pp.

- ↑ Owen, R., 1854a. Descriptive catalogue of the fossil organic remains of reptilia and pisces contained in the Museum of The Royal College of Surgeons of England: 184pp.

- ↑ Paul, G.S. 2010. The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press, 320 pp

- ↑ Benson, R.B.J. (2010). "A description of Megalosaurus bucklandii (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Bathonian of the UK and the relationships of Middle Jurassic theropods". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 158: 882. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00569.x.

- ↑ Benson, R.B.J., Carrano, M.T and Brusatte, S.L. (2010). "A new clade of archaic large-bodied predatory dinosaurs (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) that survived to the latest Mesozoic". Naturwissenschaften. 97 (1): 71–78. Bibcode:2010NW.....97...71B. doi:10.1007/s00114-009-0614-x. PMID 19826771. Supporting Information