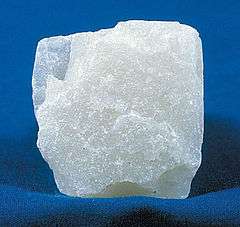

Soapstone

Soapstone (also known as steatite, or soaprock) is a talc-schist, which is a type of metamorphic rock. It is largely composed of the mineral talc and is thus rich in magnesium. It is produced by dynamothermal metamorphism and metasomatism, which occurs in the zones where tectonic plates are subducted, changing rocks by heat and pressure, with influx of fluids, but without melting. It has been a medium for carving for thousands of years.

Petrology

Petrologically, soapstone is composed dominantly of talc, with varying amounts of chlorite and amphiboles (typically tremolite, anthophyllite, and cummingtonite, obsolete name: magnesiocummingtonite), and trace to minor FeCr-oxides. It may be schistose or massive. Soapstone is formed by the metamorphism of ultramafic protoliths (e.g. dunite or serpentinite) and the metasomatism of siliceous dolostones.

By mass, steatite is approximately 67% silica and 33% magnesia, and may contain minor quantities of other oxides such as CaO or Al2O3.

Pyrophyllite, a mineral very similar to talc, is sometimes called soapstone in the generic sense since its physical characteristics and industrial uses are similar, and because it is also commonly used as a carving material. However, this mineral typically does not have such a soapy feel as soapstone.

Physical characteristics

Soapstone is relatively soft because of its high talc content, talc having a definitional value of 1 on the Mohs hardness scale. Softer grades may feel soapy when touched, hence the name. There is no fixed hardness for soapstone because the amount of talc it contains varies widely, from as little as 30% for architectural grades such as those used on countertops, to as much as 80% for carving grades. Common, non-architectural grades of soapstone can just barely be scratched with a fingernail and are thus considered to have a hardness of 2.5 on the Mohs scale.[1] Traditional soapstone used in countertops will sit at a 2.5 on the Mohs scale, while harder varieties of soapstone like Noir, Sabon, and PA can be as high as a 5 as they contain less talc.[2] If a candidate rock cannot be scratched with a knife blade (hardness of 5.5), it is not soapstone.

Soapstone is often used as an insulator for housing and electrical components, due to its durability and electrical characteristics and because it can be pressed into complex shapes before firing. Soapstone undergoes transformations when heated to temperatures of 1000–1200 °C into enstatite and cristobalite; in the Mohs scale, this corresponds to an increase in hardness to 5.5–6.5.[3]

Uses

Historical uses

Soapstone is used for inlaid designs, sculpture, coasters, and kitchen countertops and sinks. The Inuit often use soapstone for traditional carvings. Some Native American tribes and bands make bowls, cooking slabs, and other objects from soapstone; historically, this was particularly common during the Late Archaic archaeological period.[4]

Locally quarried soapstone was used for gravemarkers in 19th century northeast Georgia, US, around Dahlonega, and Cleveland, as simple field stone and "slot and tab" tombs.

Vikings hewed soapstone directly from the stone face, shaped it into cooking-pots, and sold these at home and abroad.[5]

Soapstone is sometimes used for construction of fireplace surrounds, cladding on metal woodstoves, and as the preferred material for woodburning masonry heaters because it can absorb, store and evenly radiate heat due to its high density and magnesite (MgCO3) content. It is also used for counter tops and bathroom tiling because of the ease of working the material and its property as the "quiet stone." A weathered or aged appearance will occur naturally over time as the patina is enhanced. Applying mineral oil simply darkens the appearance of the stone; it does not protect it in any way.

Tepe Yahya, an ancient trading city in southeastern Iran, was a center for the production and distribution of soapstone in the 5th–3rd millennia BC.[6] It was also used in Minoan Crete. At the Palace of Knossos, archaeological recovery has included a magnificent libation table made of steatite.[7] The Yoruba of West Nigeria utilized soapstone for several statues most notably at Esie where archaeologists have uncovered hundreds of male and female statues, about half of life size. The Yoruba of Ife also produced a miniature soapstone obelisk with metal studs called superstitiously "the staff of Oranmiyan"

Modern uses

Soapstone has been used in India for centuries as a medium for carving. Mining to meet world-wide demand for soapstone is threatening the habitat of India's tigers.[8]

In Brazil, especially in Minas Gerais, due to the abundance of soapstone mines in that Brazilian state, local artisans still craft objects from that material, including pots and pans, wine glasses, statues, jewel boxes, coasters, vases. These handicrafts are commonly sold in street markets found in cities across the state. Some of the oldest towns, notably Congonhas, Tiradentes and Ouro Preto, still have some of their streets paved with soapstone from colonial times.

Some Native Americans use soapstone for smoking pipes; numerous examples have been found among artifacts of different cultures and are still in use today. Its low heat conduction allows for prolonged smoking without the pipe's heating up uncomfortably.[9]

Some premium wood fired heating stoves are made of soapstone to take advantage of its useful thermal and fire resistant properties.

Soapstone is also used to carve Chinese seals.

Currently, soapstone is most commonly used for architectural applications, such as counter tops, floor tiles, showerbases and interior surfacing. There are active North American soapstone mines including one south of Quebec City with products marketed by Canadian Soapstone and another in Central Virginia operated by the Alberene Soapstone Company. Architectural soapstone is mined in Canada, Brazil, India and Finland and imported into the United States.[10]

Welders and fabricators use soapstone as a marker due to its resistance to heat; it remains visible when heat is applied. It has also been used for many years by seamstresses, carpenters, and other craftsmen as a marking tool because its marks are visible and not permanent.

Soapstone can be used to create molds for casting objects from soft metals, such as pewter or silver. The soft stone is easily carved and is not degraded by heating. The slick surface of soapstone allows the finished object to be easily removed.

Soapstones can be put in a freezer and later used in place of ice cubes to chill alcoholic beverages without diluting. Sometimes called 'whiskey stones', these were first introduced around 2007. Most whiskey stones feature a semi-polished finish, retaining the soft look of natural soapstone, while others are highly polished.

Steatite ceramics are low-cost biaxial porcelains of nominal composition (MgO)3(SiO2)4.[11] Steatite is used primarily for its dielectric and thermal insulating properties in applications such as tile, substrates, washers, bushings, beads and pigments.[12]

Safety

People can be exposed to soapstone in the workplace by breathing it in, skin contact, or eye contact. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has set the legal limit (Permissible exposure limit) for soapstone exposure in the workplace as 20 mppcf over an 8-hour workday. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has set a Recommended exposure limit (REL) of 6 mg/m3 total exposure and 3 mg/m3 respiratory exposure over an 8-hour workday. At levels of 3000 mg/m3, soapstone is immediately dangerous to life and health.[13]

Other names

- Combarbalite stone, exclusively mined in Combarbalá, Chile, is known for its many colors. While they are not visible during mining, they appear after refining.

- Palewa and gorara stones are types of Indian soapstone.

- A variety of other regional and marketing names for soapstone are used.[14]

Gallery

12th century Byzantine relief of Saint George and the Dragon

12th century Byzantine relief of Saint George and the Dragon

Soapstone slot & tab tomb in Dahlonega, Georgia, US.

Soapstone slot & tab tomb in Dahlonega, Georgia, US. An Egyptian carved and glazed steatite scarab amulet.

An Egyptian carved and glazed steatite scarab amulet. Steatite scarab. The Walters Art Museum.

Steatite scarab. The Walters Art Museum.

See also

- List of minerals

- List of rocks

- Talc carbonate

- Archeological Site 38CK1, Archeological Site 38CK44, and Archeological Site 38CK45

References

- ↑ “About the Hardness of Soapstone” by Soapstone.com

- ↑ "Soapstone and the Mohs Scale". www.gardenstatesoapstone.com. Retrieved 2016-11-21.

- ↑ "Some Important Aspects of the Harappan Technological Tradition," Bhan KK, Vidale M and Kenoyer JM, in Indian Archaeology in Retrospect/edited by S. Settar and Ravi Korisettar, Manohar Press, New Delhi, 2002.

- ↑ Kenneth E. Sassaman (1993-03-30). Early Pottery in the Southeast: Tradition and Innovation in Cooking Technology. University Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0670-0.

- ↑ Else Rosendahl, The Vikings, The Penguin Press, 1987, page 105

- ↑ "Tepe Yahya," Encyclopædia Britannica, 2004. Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. 3 January 2004, Britannica.com

- ↑ C.Michael Hogan (2007) "Knossos Fieldnotes", The Modern Antiquarian

- ↑ Barnett, Antony (2003-06-22). "West's love of talc threatens India's tigers". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- ↑ Witthoft, J.G., 1949, "Stone Pipes of the Historic Cherokees", Southern Indian Studies 1(2):43–62.

- ↑ "Soapstone gives countertops, tiles a look that's both new and old". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2014-01-11.

- ↑ Royalty Minerals Ltd., Mumbai, India.

- ↑ Superior Technical Ceramics Corp., St. Albans, Vermont, USA.

- ↑ "CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards - Soapstone (containing less than 1% quartz)". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-21.

- ↑ GemRocks: Soapstone

- ↑ Hoysala.in

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to soapstone or steatite. |

- Soapstone Calculated Refractory Data w/ Technical Properties Converter (Incl. Soapstone Volume vs. Weight measuring units)

- Ancient soapstone bowl (The Central States Archaeological Journal)

- Soapstone Native American quarries, Maryland (Geological Society of America)

- Prehistoric soapstone use in northeastern Maryland (Antiquity Journal)

- The Blue Rock Soapstone Quarry, Yancey County, NC (North Carolina Office of State Archaeology)

- CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- Steatite historical marker in Decatur, Georgia