Standard weight in fish

Standard weight in fish is the typical or expected weight at a given total length for a specific species of fish. Most standard weight equations are for freshwater fish species.

Weight-length curves are developed by weighing and measuring samples of fish from the population. Methods of obtaining such samples include creel surveys, or measurements of fish caught by commercial fishermen, recreational fishermen and/or by the researchers themselves. Some scientists use cast nets, trotlines, or other means to catch many individual fish at once for measurement. To determine a standard weight equation, several data sets or weight-length relationships representing a species across its range are used.

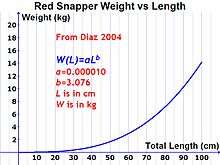

As fish grow in length, they increase in weight. The relationship between weight and length is not linear. The relationship between length (L) and weight (W) can be expressed as:

When the equation is for standard weight, the standard weight for a given length is written as Ws. The exponent b is close to 3.0 for most species. The coefficient a varies between species. If the exponent b is greater than three for a certain fish species, that species tends to become relatively fatter or have more girth as it grows longer. For largemouth bass, the value of b is 3.273. If the exponent b is less than three for a certain fish species, that species tends to be more streamlined. For burbot, the value of b is 2.898.[3] While the standard weight for a largemouth bass that is 500 mm long is about 2 kg, the standard weight for a burbot that is 500 mm long is only about 0.9 kg.

Standard weight curves are often based on the 75th percentile weight data rather than the average of all the data available. Murphy et al. (1991) suggested that it is preferable that standard weight equations represent the entire geographical range of a species, and that they be used for comparison purposes rather than management targets.[4] Practically, weight-length equations are often developed for sub-populations from specific geographic areas, but these are different from standard weight relationships.

Factors affecting standard weight

Length measurements reported for fish may be of the fish’s total length, fork length, or maximum standard length. For standard weight equations, the total length is used.

In some species, male and female fish have different standard weight curves. For example, Anderson and Neumann report different standard weight equations for male and female paddlefish.[5] Some researchers have also reported separate standard weight equations when a species has lentic (living in still water) and lotic (living in flowing water) populations. For example, separate standard weight equations have been published for lentic and lotic rainbow trout.[6]

Applications

Standard weight is used as a basis for comparison to assess the health of an individual or group of fish. Generally, fish that are heavier than the standard weight for their length are considered healthier, having more energy reserves for normal activities, growth and reproduction.[7]

Fish may weigh less than expected for their length for many reasons, and a scientist must consider more information before assigning a cause. One of the simplest reasons is lack of food/prey. Lack of prey in turn could be the result of overpopulation of the predator, for example, competition from another predator species, unsuitability of the environment for reproduction of the prey, or dying of the prey for some reason. A fish may also weigh less than expected due to a change in activity level or metabolism due to some environmental factor.

Standard weight equations, together with some measure of a fish’s condition, can be used in aquaculture to measure the effectiveness of various feeding, temperature control, containment or other practices. The actual measure of a fish’s condition using standard weight is done different ways.

The relative weight (Wr) of an individual fish is its actual weight divided by its standard weight, times 100%.[8] A fish of “normal” weight has a relative weight of 100 percent. The relative weight of a fish does not indicate its health on a continuous scale from 0 -100%, however. For example, Simpkins et al. found that juvenile rainbow trout with a condition index of less than 80% were at a high risk of dying.[9] Relative weight is one of several common measures of condition used in fisheries assessment and management.[10]

Fulton’s condition factor, K, is another measure of an individual fish’s health that uses standard weight.[11] Proposed by Fulton in 1904, it assumes that the standard weight of a fish is proportional to the cube of its length:

where W is the whole body wet weight in grams and L is the length in centimeters; the factor 100 is used to bring K close to a value of one.

See also

References

- ↑ Henson, J. C. 1991. Quantitative description and development of a species-specific growth form for largemouth bass, with application to the relative weight index. Master's thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station.

- ↑ Fisher, S., D. Willis, and K. Pope. 1996. An assessment of burbot (Lota lota) weight-length data from North American populations. Canadian Journal of Zoology 74:570{575

- ↑ R. O. Anderson and R. M. Neumann, Length, Weight, and Associated Structural Indices, in Fisheries Techniques, second edition, B.E. Murphy and D.W. Willis, eds., American Fisheries Society, 1996

- ↑ Murphy, B. R., Willis, D.W., and Springer, T.A The Relative Weight Index in Fisheries Management: Status and Needs. Fisheries, 16(2):30-38, 1991

- ↑ R. O. Anderson and R. M. Neumann, Length, Weight, and Associated Structural Indices, in Fisheries Techniques, second edition, B.E. Murphy and D.W. Willis, eds., American Fisheries Society, 1996

- ↑ Simpkins, D. G. and W. A. Hubert. Proposed revision of the standard weight equation for rainbow trout. Journal of Freshwater Ecology 11:319-326, 1996

- ↑ Ogle, D. FishR Vignette - Fish Condition and Relative Weights, June, 2013 Northland College

- ↑ Wege, G. W. and R. O. Anderson. 1978. Relative weight (Wr): A new index of condition for largemouth bass. In G. D. Novinger and J. G. Dillard (editors), New Approaches to the Management of Small Impoundments, Special Publication, volume 5, pp. 79-91, American Fisheries Society

- ↑ Simpkins, D.G., Hubert, W.A., Martinez Del Rio, C., Rule, D.C., Physiological responses of juvenile rainbow trout to fasting and swimming activity: effects on body composition and condition indexes. Trans. American Fisheries Society 132:576-589, 2003

- ↑ Blackwell, B.G., Brown, M.L., and Willis, D.W. Relative Weight (Wr) Status and Current Use in Fisheries Assessment and Management Reviews in Fisheries Science, 8(1): 1–44 (2000)

- ↑ Nash, R.D.M., Valencia, A.H., Geffen, A. J. The origin of Fulton’s condition factor – setting the record straight. Fisheries 31:5, 236-238, 2006

Examples in the literature

- Beamesderfer, R.C. A Standard Weight (Ws) Equation for White Sturgeon. Calif. Fish and Game 79(2):63-69, 1993

- Bister, T.J. Proposed Standard Weight (Ws) Equations and Standard Length Categories for 18 Warmwater Nongame and Riverine Fish Species North American Journal of Fisheries Management 20:570-574, 2000

External links

- Ogle, D. FishR Vignette - Fish Condition and Relative Weights, June, 2013 This article by Dr. Ogle includes a summary table of standard weight equations for several dozen species of fish with literature references. Accessed 11/28/2013

- Wright, R.A. Relative weight: an easy to measure index of fish condition. Alabama Cooperative Extension System ANR-1193, 2000