Stable Salt Reactor

The Stable Salt Reactor (SSR) is a nuclear reactor design proposed by Moltex Energy LLP[1] based in the UK. It represents a breakthrough in molten salt reactor technology, with the potential to make nuclear power safer and cheaper.

Studies conducted by Moltex Energy show that liquid salt fuelled reactors are the only design configuration which have radically improved safety characteristics. These reactors do not need expensive containment structures and components to keep them in a stable condition. In the Chernobyl accident the two most troublesome by-products were caesium and iodine in gaseous form, which are harmful to land and people. This hazard is inherent with any solid fuelled reactor, but in a molten salt these products do not exist in the form of a gas, they are stable salts which are not hazardous to the public in most accident scenarios.

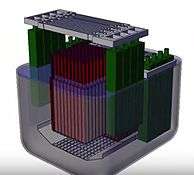

Moltex Energy have used computational fluid dynamics to prove the feasibility of a static fuel concept. Solid fuel in fuel rods is replaced by molten salt fuel, in assemblies that are very similar to current light water reactor technology. The result is a simple, low cost reactor that uses components from today’s nuclear fleet but has all the safety advantages of a molten salt fuel.

Stable Salt Technology

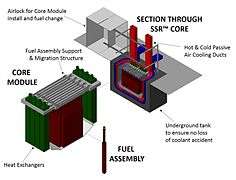

The basic unit of the reactor core is the fuel assembly. Each assembly contains nearly 400 fuel tubes of 10mm diameter with a 1mm helical wire wrap filled to a height of 1.6 metres with fuel salt. The tubes have diving bell gas vents at the top to allow fission gasses to escape.

An unusual design feature of the reactor is that its core is rectangular in shape. This is neutronically inefficient compared to a cylindrical core but allows for simpler movement of fuel assemblies, and extension of the core as required simply by adding additional modules.

The assemblies move laterally through the core, with fresh assemblies entering at the sides in opposite directions, similar to the refuelling of CANDU reactors. They are raised only slightly to move them into an adjacent slot, remaining in the coolant at all times.

Modular Construction

The reactor core is made up of modules, each with a thermal output of 375MW, containing 10 rows of 10 fuel assemblies, upper and lower support grids, heat exchangers, pumps, control assemblies and instrumentation. Two or more of these modules are assembled side by side into a rectangular reactor tank. A 1200MWe reactor is possible in a tank that can fit on the back of a truck, making the technology significantly more compact than today’s reactors.

The modules (without fuel assemblies) are delivered to the construction site pre-assembled and pre-tested as single road transportable components. They are installed into the stainless steel tank when the civil works phase is complete during commissioning.

The upper part of the reactor consists of an argon containment dome, incorporating two crane type systems, a low load device designed to move fuel assemblies within the reactor core and a high load device designed to raise and lower fuel assemblies into the coolant and to replace entire modules should that be necessary. All reactor maintenance is carried out remotely.

Safety

The Stable Salt Reactor was designed with intrinsic safety characteristics being the first line of defence. There is no operator or active system required to maintain the reactor in a safe and stable state. The following are primary intrinsic safety features behind the SSR:

Reactivity control

The SSR is self-controlling and no mechanical control is required. There is zero excess reactivity at any time. This is made possible by the combination of a high negative temperature coefficient of reactivity and the ability to continually extract heat from the fuel tubes. As heat is taken out of the system the temperature drops causing the reactivity to go up. When the reactor heats up the reactivity goes down making it stable at all times.

Volatile source term

Use of molten salt fuel with the appropriate chemistry eliminates the hazardous volatile iodine and caesium source terms, making multi-layered containment unnecessary in preventing airborne radioactive plumes in severe accident scenarios.

No high pressures

High pressures within a reactor provide a driving force for dispersion of radioactive materials from the reactor. Use of molten salt fuel and coolant, and physical separation of the steam generating system from the radioactive core by use of a secondary coolant loop, eliminate those driving forces from the reactor. High pressures within fuel tubes are avoided by venting off fission gases.

Chemical reactivity

Zirconium in a PWR and sodium in fast reactors both create the potential for severe explosion and fire risks. There are no chemically reactive materials used in the SSR.

Decay heat removal

When nuclear reactors shutdown approximately 1% of power continues to be generated. In conventional reactors, removing this heat passively is challenging because of their low temperatures. The SSR operates at much higher temperatures so this heat can be rapidly transferred away from the core. In the event of a reactor shutdown and failure of all active heat removal systems in the SSR, decay heat from the core dissipates into air cooling ducts around the perimeter of the tank that operate continually. The main heat transfer mechanism is radiative. Heat transfer goes up substantially with temperature so is negligible at operating conditions but is sufficient for decay heat removal at higher accident temperatures. The reactor components are not damaged during this process and the plant can be restarted afterwards.

Fuel & Materials

The fuel is made up of two thirds sodium chloride (table salt) and one third plutonium and mixed lanthanide/actinide trichlorides. Fuel for the initial six reactors is expected to come from stocks of pure plutonium dioxide from PUREX reprocessed conventional spent nuclear fuel, mixed with pure depleted uranium trichloride. Further fuel can come from reprocessed nuclear waste from today’s fleet of reactors.

Being a trichloride, it is more thermodynamically stable than the corresponding fluoride salts and can therefore be maintained in a strongly reducing state by contact with sacrificial nuclear grade zirconium metal added as a coating on, or an insert within, the fuel tube. As a result, the fuel tube can be made from standard nuclear certified steel without risk of corrosion. Since the reactor operates in the fast spectrum, the tubes will be exposed to very high neutron flux and suffer high damage (dpa) levels, estimated at 100-200 dpa over the tube life. Highly neutron damage tolerant steels such as PE16 will therefore be used for the tubes. Assessment is also being carried out on other steels with fast neutron data such as HT9, NF616 and 15-15Ti.

The average power density in the fuel salt is 150kW/l which allows a very generous margin for salt temperature below its boiling point. Power peaking to double this level for substantial periods would not exceed the safe operating conditions for the fuel tube.

Coolant

The coolant salt in the reactor tank is a sodium zirconium fluoride mixture. The zirconium is not nuclear grade and still contains ~2% hafnium. This has minimal effect on core reactivity but makes the coolant salt low cost and a highly effective neutron shield. One metre of coolant reduces neutron flux by 4 orders of magnitude. All components in the SSR are protected by this coolant shield.

The coolant also contains 1mol% zirconium metal (which dissolves forming 2mol% ZrF2). This reduces its redox potential to a level making it virtually non-corrosive to standard steels. The reactor tank, support structures and heat exchangers can therefore be constructed from standard 316L stainless steel.

The coolant salt is circulated through the reactor core by four pumps attached to the heat exchangers in each module. Flow rates are modest, approximately 1m/sec with resulting low requirement for pump power. There is redundancy to continue operation in the event of a pump failure.

A Solution to the Nuclear Waste Legacy

Most countries that use nuclear power choose to store spent nuclear fuel deep underground until its radioactivity has reduced to levels similar to natural uranium. Acting as a wasteburner, the SSR offers a different way to manage this waste.

Operating in the fast spectrum, the SSR is effective at transmuting long lived actinides into more stable isotopes. Today’s reactors that are fuelled by reprocessed spent fuel need very high purity plutonium to form a stable pellet. The SSR can have any level of lanthanide and actinide contamination in its fuel as long as it can still go critical. This low level of purity greatly simplifies the reprocessing method for existing waste.

The method used is based on pyro-processing and is well understood. A 2016 report by the Canadian National Laboratories on reprocessing of CANDU fuel estimates that pyro-processing would be about half the cost of more conventional reprocessing. Pyroprocessing for the SSR uses only one third of the steps of conventional pyroprocessing which will make it even cheaper. It is potentially competitive with the cost of manufacturing fresh fuel from mined uranium.

The waste stream from the SSR will be in the form of solid salt in tubes. This can be vitrified and stored underground for over 100,000 years as is planned today or it can be reprocessed. Fission products would be separated out and safely stored at ground level for the few hundred years needed for them to decay to levels similar to uranium ore. The troublesome long lived actinides and the remaining fuel go back into the reactor where they are burnt and transmuted into more stable isotopes.

Other Stable Salt Reactor designs

Stable Salt Reactor technology is highly flexible and can be adapted to several different reactor designs. The use of molten salt fuel in standard fuel assemblies allows Stable Salt versions of many of the large variety of nuclear reactors considered for development worldwide. The focus today however is to allow rapid development and roll out of low cost reactors.

Moltex Energy is focussed on deployment of the fast spectrum SSR-Wasteburner discussed above. This decision is primarily driven by the lower technical challenges and lower predicted cost of this reactor.

In the longer term the fundamental breakthrough of molten salt in tubes opens up other options. These have been developed to a conceptual level to confirm their feasibility. They include:

- Uranium Burner (SSR-U) This is a thermal spectrum reactor burning low enriched uranium which may be more suited to nations without an existing nuclear fleet and waste concern. It is moderated with graphite as part of the fuel assembly.

- Thorium Breeder (SSR-Th) This reactor contains thorium in the coolant salt which can breed new fuel. Thorium is an abundant fuel source that can provide energy security to nations without indigenous uranium reserves.

With this range of reactor options and the large global reserves of uranium and thorium available the Stable Salt Reactor can fuel the planet for several thousands of years.

Economics

The urgency of the climate crisis is pushing the nuclear industry to develop cheaper technologies which can achieve wide scale deployment.

The overnight capital cost[2] of the Stable Salt Reactor is based on an independent cost estimate[3] by a leading UK nuclear engineering firm. The result is $1950/kW. For comparison, the capital cost of a modern pulverised coal power station in the U.S. is $3250/kW and the cost of large-scale nuclear is $5500/kW. Further reductions to this overnight cost are expected for modularised, factory based construction.

This low capital cost results in a Levelised Cost of Electricity (LCOE) of just $44.64/MWh with substantial potential to be yet lower, because of the greater simplicity and intrinsic safety of the SSR.

The International Energy Agency predicts that nuclear will maintain a constant small role in global energy supply with a market opportunity of 219GWe up to 2040. With the improved economics of the SSR, Moltex Energy predicts that it has the potential to access a market of over 1300GWe by 2040.

Next steps

A patent[4] was granted in 2014. A design has been developed and a safety case is well under way, to begin formal discussions with nuclear regulatory authorities.

External links

- Stable Salt Reactor Technology Introduction, YouTube video

- Moltex Energy SSR Fly Through, YouTube video

References

- ↑ "Moltex Energy | Safer Cheaper Cleaner Nuclear | Stable Salt Reactors | SSR". www.moltexenergy.com. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑ "Moltex Energy sees UK, Canada SMR licensing as springboard to Asia | Nuclear Energy Insider". analysis.nuclearenergyinsider.com. Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- ↑ Brooking, Jon (2015-01-01). "Design review and hazop studies for stable salt reactor".

- ↑ "Patent GB2508537A" (PDF).