Spinal anaesthesia

| Spinal anaesthesia | |

|---|---|

| Intervention | |

|

Backflow of cerebrospinal fluid through a 25 gauge spinal needle after puncture of the arachnoid mater during initiation of spinal anaesthesia | |

| MeSH | D000775 |

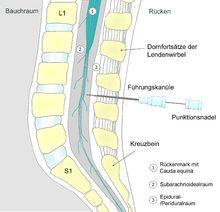

Spinal anaesthesia (or spinal anesthesia), also called spinal block, subarachnoid block, intradural block and intrathecal block,[1] is a form of regional anaesthesia involving the injection of a local anaesthetic into the subarachnoid space, generally through a fine needle, usually 9 cm (3.5 in) long. For obese patients longer needles are available (12.7 cm / 5 inches). The tip of the spinal needle has a point or small bevel. Recently, pencil point needles have been made available (Whitacre, Sprotte, Gertie Marx and others).[2]

Medical uses

Spinal anaesthesia is a commonly used technique, either on its own or in combination with sedation or general anaesthesia. Examples of uses include:

- Orthopaedic surgery on the pelvis, hip, femur, knee, tibia, and ankle, including arthroplasty and joint replacement

- Vascular surgery on the legs

- Endovascular aortic aneurysm repair

- Hernia (inguinal or epigastric)

- Haemorrhoidectomy

- Nephrectomy and cystectomy in combination with general anaesthesia

- Transurethral resection of the prostate and transurethral resection of bladder tumours

- Hysterectomy in different techniques used

- Caesarean sections

Spinal anaesthesia is the technique of choice for Caesarean section as it avoids a general anaesthetic and the risk of failed intubation (which is approximately 1 in 250 in pregnant women). It also means the mother is conscious and the partner is able to be present at the birth of the child. The post operative analgesia from intrathecal opioids in addition to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is also good.

If surgery allows, spinal anaesthesia is very useful in patients with severe respiratory disease such as COPD as it avoids intubation and ventilation. It may also be useful in patients where anatomical abnormalities may make tracheal intubation very difficult.

Contraindications

- Non-availability of patient's consent

- Local infection or sepsis at the site of lumbar puncture

- Bleeding disorders, thrombocytopaenia, or systemic anticoagulation (secondary to an increased risk of a spinal epidural hematoma)

- Space occupying lesions of the brain

- Anatomical disorders of the spine

- Hypovolaemia e.g. following massive haemorrhage, including in obstetric patients

Risks/Complications

Can be broadly classified as immediate (on the operating table) or late (in the post-anaesthesia care unit or ward):

- Hypotension (Neurogenic shock) - Due to sympathetic nervous system blockade. Common but usually easily treated with intravenous fluid and sympathomimetic drugs such as Ephedrine, Phenylephrine or Metaraminol

- Post dural puncture head ache or post spinal head ache - Associated with the size and type of spinal needle used

- Cauda equina injury - very rare, due to the insertion site being too high

- Cardiac arrest - very rare, usually related to the underlying medical condition of the patient

- Spinal canal haematoma, with or without subsequent neurological sequelae due to compression of the spinal nerves. Urgent CT/MRI to confirm the diagnosis followed by urgent surgical decompression to avoid permanent neurological damage

- Epidural abscess, again with potential permanent neurological damage. May present as meningitis or and abscess with back pain, fever, lower limb neurological impairment and loss of bladder/bowel function. Urgent CT/MRI confirms the diagnosis followed by antibiotics and urgent surgical drainage

Technique

Regardless of the anaesthetic agent (drug) used, the desired effect is to block the transmission of afferent nerve signals from peripheral nociceptors. Sensory signals from the site are blocked, thereby eliminating pain. The degree of neuronal blockade depends on the amount and concentration of local anaesthetic used and the properties of the axon. Thin unmyelinated C-fibres associated with pain are blocked first, while thick, heavily myelinated A-alpha motor neurons are blocked moderately. Heavily myelinated, small preganglionic sympathetic fibers are blocked first. The desired result is total numbness of the area. A pressure sensation is permissible and often occurs due to incomplete blockade of the thicker A-beta mechanoreceptors. This allows surgical procedures to be performed with no painful sensation to the person undergoing the procedure.

Some sedation is sometimes provided to help the patient relax and pass the time during the procedure, but with a successful spinal anaesthetic the surgery can be performed with the patient wide awake.

Limitations

Spinal anaesthetics are typically limited to procedures involving most structures below the upper abdomen. To administer a spinal anaesthetic to higher levels may affect the ability to breathe by paralysing the intercostal respiratory muscles, or even the diaphragm in extreme cases (called a "high spinal", or a "total spinal", with which consciousness is lost), as well as the body's ability to control the heart rate via the cardiac accelerator fibres. Also, injection of spinal anaesthesia higher than the level of L1 can cause damage to the spinal cord, and is therefore usually not done.

Difference from epidural anesthesia

Epidural anesthesia is a technique whereby a local anesthetic drug is injected through a catheter placed into the epidural space. This technique has some similarity to spinal anesthesia, both are neuraxial, and the two techniques may be easily confused with each other. Differences include:

- A spinal anaesthetic delivers drug to the intrathecal space (the CSF), and acts on the spinal cord directly. An epidural delivers drugs outside the dura (outside CSF), and has its main effect on nerve roots leaving the dura at the level of the epidural, rather than on the spinal cord itself.

- A spinal gives profound block of all motor and sensory function below the level of injection, whereas an epidural blocks a 'band' of nerve roots around the site of injection, with normal function above, and close-to-normal function below the levels blocked.

- The injected dose for an epidural is larger, being about 10–20 mL compared to 1.5–3.5 mL in a spinal.

- In an epidural, an indwelling catheter may be placed that serves for additional injections, while a spinal is almost always a one-shot only.

- The onset of analgesia is approximately 25–30 minutes in an epidural, while it is approximately 5 minutes in a spinal.

- An epidural often does not cause as significant a neuromuscular block as a spinal, unless specific local anesthetics are also used which block motor fibres as readily as sensory nerve fibres.

- An epidural may be given at a cervical, thoracic, or lumbar site, while a spinal must be injected below L2 to avoid piercing the spinal cord.

Injected substances

Bupivacaine (Marcaine) is the local anaesthetic most commonly used, although lidocaine (lignocaine), tetracaine, procaine, ropivacaine, levobupivicaine, prilocaine and cinchocaine may also be used. Commonly opioids are added to improve the block and provide post-operative pain relief, examples include morphine, fentanyl, diamorphine or buprenorphine. Non-opioids like clonidine may also be added to prolong the duration of analgesia (although Clonidine may cause hypotension). In the United Kingdom, since 2004 the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends that spinal anaesthesia for Caesarean section is supplemented with intrathecal diamorphine and this combination is now the modal form of anaesthesia for this indication in that country. The peculiar legal status of diamorphine (heroin) means that this cannot easily occur elsewhere.

Baricity refers to the density of a substance compared to the density of human cerebrospinal fluid. Baricity is used in anaesthesia to determine the manner in which a particular drug will spread in the intrathecal space. Usually, the hyperbaric, (for example, hyperbaric bupivacaine) is chosen, as its spread can be effectively and predictably controlled by the Anaesthesiologist or Nurse Anesthetist, by tilting the patient. Hyperbaric solutions are made more dense by adding glucose to the mixture.

Baricity is one factor that determines the spread of a spinal anaesthetic but the effect of adding a solute to a solvent, i.e. solvation or dissolution, also has an effect on the spread of the spinal anaesthetic. In tetracaine spinal anaesthesia, it was discovered that the rate of onset of analgesia was faster and the maximum level of analgesia was higher with a 10% glucose solution than with a 5% glucose spinal anaesthetic solution. Also, the amount of ephedrine required was less in the patients who received the 5% glucose solution.[3] In another study this time with 0.5% bupivacaine the mean maximum extent of sensory block was significantly higher with 8% glucose (T3.6) than with 0.83% glucose (T7.2) or 0.33% glucose (T9.5). Also the rate of onset of sensory block to T12 was fastest with solutions containing 8% glucose.[4]

History

The first spinal analgesia was administered in 1885 by James Leonard Corning (1855–1923), a neurologist in New York.[5] He was experimenting with cocaine on the spinal nerves of a dog when he accidentally pierced the dura mater.

The first planned spinal anaesthesia for surgery in man was administered by August Bier (1861–1949) on 16 August 1898, in Kiel, when he injected 3 ml of 0.5% cocaine solution into a 34-year-old labourer.[6] After using it on 6 patients, he and his assistant each injected cocaine into the other's spine. They recommended it for surgeries of legs, but gave it up due to the toxicity of cocaine.

Society and culture

Current usage of this technique is waning in the developed world, with epidural analgesia or combined spinal-epidural anaesthesia emerging as the techniques of choice where the cost of the disposable 'kit' is not an issue.

However spinal analgesia is the mainstay of anaesthesia in countries like India, Pakistan and parts of Africa, excluding the major centres. Thousands of spinal anaesthetics are administered daily in hospitals and nursing homes. At a low cost, a surgery of up to two hours duration can be performed below the umbilicus of the patient.

See also

References

- ↑ Bronwen Jean Bryant; Kathleen Mary Knights (2011). Pharmacology for Health Professionals. Elsevier Australia. pp. 273–. ISBN 978-0-7295-3929-6.

- ↑ Serpell, M. G.; Fettes, P. D. W.; Wildsmith, J. A. W. (1 November 2002). "Pencil point spinal needles and neurological damage". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 89 (5): 800–801. doi:10.1093/bja/89.5.800.

- ↑ Effect of glucose concentration on the subarachnoid spread of tetracaine in the parturient

- ↑ Effect of Glucose Concentration on the Intrathecal Spread of 0.5% Bupivacaine

- ↑ Corning J. L. N.Y. Med. J. 1885, 42, 483 (reprinted in 'Classical File', Survey of Anesthesiology 1960, 4, 332)

- ↑ Bier A. Versuche über Cocainisirung des Rückenmarkes. Deutsch Zeitschrift für Chirurgie 1899;51:361. (translated and reprinted in 'Classical File', Survey of Anesthesiology 1962, 6, 352)

External links

- Transparent reality simulation of spinal anaesthesia

- Various diagrams of needles for Lumbar puncture, Epidural, Spinal Anesthesia, etc