Lecithin

Lecithin (from the Greek lekithos, "egg yolk") is a generic term to designate any group of yellow-brownish fatty substances occurring in animal and plant tissues, which are amphiphilic - they attract both water and fatty substances (and so are both hydrophilic and lipophilic), and are used for smoothing food textures, dissolving powders (emulsifiers), homogenizing liquid mixtures, and repelling sticking materials.[1][2]

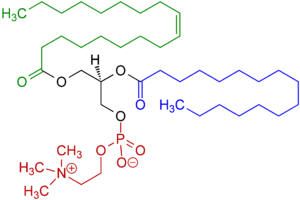

Lecithins are usually phospholipids, composed of phosphoric acid with choline, glycerol or other fatty acids usually glycolipids or triglyceride. Glycerophospholipids in lecithin include phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylserine, and phosphatidic acid.[3]

Lecithin was first isolated in 1845 by the French chemist and pharmacist Theodore Gobley.[4] In 1850, he named the phosphatidylcholine lécithine.[5] Gobley originally isolated lecithin from egg yolk—λέκιθος lekithos is "egg yolk" in Ancient Greek—and established the complete chemical formula of phosphatidylcholine in 1874;[6] in between, he had demonstrated the presence of lecithin in a variety of biological matters, including venous blood, bile, human brain tissue, fish eggs, fish roe, and chicken and sheep brain.

Lecithin can easily be extracted chemically using any non-polar solvent such as hexane, ethanol, acetone, petroleum ether, benzene, etc., or extraction can be done mechanically. It is usually available from sources such as soybeans, eggs, milk, marine sources, rapeseed, cottonseed, and sunflower. It has low solubility in water, but is an excellent emulsifier. In aqueous solution, its phospholipids can form either liposomes, bilayer sheets, micelles, or lamellar structures, depending on hydration and temperature. This results in a type of surfactant that usually is classified as amphipathic. Lecithin is sold as a food additive and dietary supplement. In cooking, it is sometimes used as an emulsifier and to prevent sticking, for example in nonstick cooking spray.

Biology

Lecithin, as a food additive, is also a dietary source of several active compounds: Choline and its metabolites are needed for several physiological purposes, including cell membrane signaling and cholinergic neurotransmission,[7] although its exact function has not been determined, and the involvement of choline in long-term health and development of clinical disorders, such as cardiovascular diseases, cognitive decline in aging and regulation of blood lipid levels, has not been well defined, and remains under research in 2015.[8]

While lecithin is also a rich source of a variety of types of dietary fats, the small amounts of lecithin typically used for food additive purposes mean it is not a significant source of fats. Lecithin is a source for methyl groups via its metabolite, trimethylglycine (betaine) although this is mostly consumed from plants (and is abundant in sugar beets for example).[9]

Phosphatidylcholine occurs in all cellular organisms, being one of the major components of the phospholipid portion of the cell membrane.[10]

Production

Commercial lecithin, as used by food manufacturers, is a mixture of phospholipids in oil. The lecithin can be obtained by water degumming the extracted oil of seeds. It is a mixture of various phospholipids, and the composition depends on the origin of the lecithin. A major source of lecithin is soybean oil. Because of the EU requirement to declare additions of allergens in foods, in addition to regulations regarding genetically modified crops, a gradual shift to other sources of lecithin (e.g., sunflower oil) is taking place. The main phospholipids in lecithin from soya and sunflower are phosphatidyl choline, phosphatidyl inositol, phosphatidyl ethanolamine, and phosphatidic acid. They often are abbreviated to PC, PI, PE, and PA, respectively. Purified phospholipids are produced by companies commercially.

Hydrolysed lecithin

To modify the performance of lecithin to make it suitable for the product to which it is added, it may be hydrolysed enzymatically. In hydrolysed lecithins, a portion of the phospholipids have one fatty acid removed by phospholipase. Such phospholipids are called lysophospholipids. The most commonly used phospholipase is phospholipase A2, which removes the fatty acid at the C2 position of glycerol. Lecithins may also be modified by a process called fractionation. During this process, lecithin is mixed with an alcohol, usually ethanol. Some phospholipids, such as phosphatidylcholine, have good solubility in ethanol, whereas most other phospholipids do not dissolve well in ethanol. The ethanol is separated from the lecithin sludge, after which the ethanol is removed by evaporation to obtain a phosphatidylcholine-enriched lecithin fraction.

Genetically modified crops as a source of lecithin

As described above, lecithin is highly processed. Therefore, genetically modified (GM) protein or DNA from the original GM crop from which it is derived often is undetectable – in other words, it is not substantially different from lecithin derived from non-GM crops.[11] Nonetheless, consumer concerns about genetically modified food have extended to highly purified derivatives from GM food, such as lecithin.[12] This concern led to policy and regulatory changes in the European Union in 2000, when Commission Regulation (EC) 50/2000 was passed[13] which required labelling of food containing additives derived from GMOs, including lecithin. Because it is nearly impossible to detect the origin of derivatives such as lecithin, the European regulations require those who wish to sell lecithin in Europe to use a meticulous, but essential system of identity preservation (IP).[11][14]

Properties and applications

Lecithin has emulsification and lubricant properties, and is a surfactant. It can be totally metabolized (see Inositol) by humans, so is well tolerated by humans and nontoxic when ingested; some other emulsifiers can only be excreted via the kidneys.

The major components of commercial soybean-derived lecithin are:[15]

- 33–35% Soybean oil

- 20–21% Inositol phosphatides

- 19–21% Phosphatidylcholine

- 8–20% Phosphatidylethanolamine

- 5–11% Other phosphatides

- 5% Free carbohydrates

- 2–5% Sterols

- 1% Moisture

Lecithin is used for applications in human food, animal feed, pharmaceuticals, paints, and other industrial applications.

Applications include:

- In the pharmaceutical industry, it acts as a wetting, stabilizing agent and a choline enrichment carrier, helps in emulsifications and encapsulation, and is a good dispersing agent. It can be used in manufacture of intravenous fat infusions and for therapeutic use.

- In animal feed, it enriches fat and protein and improves pelletization.

- In the paint industry, it forms protective coatings for surfaces with painting and printing ink, has antioxidant properties, helps as a rust inhibitor, is a colour-intensifying agent, catalyst, conditioning aid modifier, and dispersing aid; it is a good stabilizing and suspending agent, emulsifier, and wetting agent, helps in maintaining uniform mixture of several pigments, helps in grinding of metal oxide pigments, is a spreading and mixing aid, prevents hard settling of pigments, eliminates foam in water-based paints, and helps in fast dispersion of latex-based paints.

- Lecithin also may be used as a release agent for plastics, an antisludge additive in motor lubricants, an antigumming agent in gasoline, and an emulsifier, spreading agent, and antioxidant in textile, rubber, and other industries.

Food additive

The nontoxicity of lecithin leads to its use with food, as an additive or in food preparation. It is used commercially in foods requiring a natural emulsifier or lubricant.

In confectionery, it reduces viscosity, replaces more expensive ingredients, controls sugar crystallization and the flow properties of chocolate, helps in the homogeneous mixing of ingredients, improves shelf life for some products, and can be used as a coating. In emulsions and fat spreads, it stabilizes emulsions, reduces spattering during frying, improves texture of spreads and flavour release. In doughs and bakery, it reduces fat and egg requirements, helps even distribution of ingredients in dough, stabilizes fermentation, increases volume, protects yeast cells in dough when frozen, and acts as a releasing agent to prevent sticking and simplify cleaning. It improves wetting properties of hydrophilic powders (e.g., low-fat proteins) and lipophilic powders (e.g., cocoa powder), controls dust, and helps complete dispersion in water.[16] Lecithin keeps cocoa and cocoa butter in a candy bar from separating. It can be used as a component of cooking sprays to prevent sticking and as a releasing agent. In margarines, especially those containing high levels of fat (>75%), lecithin is added as an 'antispattering' agent for shallow frying.[17]

Lecithin is approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for human consumption with the status "generally recognized as safe". Lecithin is admitted by the EU as a food additive, designated as E322.[18]

Dietary supplement

Because it contains phosphatidylcholines, lecithin is a source of choline, an essential nutrient.[19][20] Clinical studies have shown benefit in acne, in improving liver function, and in lowering cholesterol, but clinical studies in dementia and dyskinesias have found no benefit.[20][21][22] An earlier study using a small sample (20 men divided in 3 groups) did not detect statistically significant short term (2–4 weeks) effects on cholesterol in hyperlipidaemic men.[23]

La Leche League recommends its use to prevent blocked or plugged milk ducts which can lead to mastitis in breastfeeding women.[24]

Egg-derived lecithin is not usually a concern for those allergic to eggs since commercially available egg lecithin is highly purified and devoid of allergy-causing egg proteins.[25] Egg lecithin is not a concern for those on low-cholesterol diets, because the lecithin found in eggs markedly inhibits the absorption of the cholesterol contained in eggs.[26]

Religious restrictions

Soy-derived lecithin is considered by some to be kitniyot and prohibited on Passover for Ashkenazi Jews when many grain-based foods are forbidden, but not at other times. This does not necessarily affect Sephardi Jews, who do not have the same restrictions on rice and kitniyot during Pesach/Passover.[27]

Muslims are not forbidden to eat lecithin per se; however, since it may be derived from animal as well as plant sources, care must be taken to ensure this source is halal. Lecithin derived from plants and egg yolks is permissible, as is that derived from animals slaughtered according to the rules of dhabihah.[28]

Research

Research studies claim to show soy-derived lecithin has significant effects on lowering serum cholesterol and triglycerides, while increasing HDL ("good cholesterol") levels in the blood of rats.[29][30]

A growing body of evidence indicates lecithin is converted by gut bacteria into trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), which is released into circulation, and may with time contribute to atherosclerosis and heart attacks.[31][32][33]

References

- ↑ Lecithin (Merriam Webster Dictionary online)

- ↑ Lecithins: Sources, Manufacture & Uses, Bernard F. Szuha, Pub: The American Oil Chemist's Society, ISBN 0-935315-27-6, Chapter 7, page 109. (Google Books)

- ↑ Food Additives Databook Page 367 and on (Google Books)

- ↑ Gobley, Theodore (1846). "Recherches chimiques sur le jaune d'œuf" [Chemical researches on egg yolk]. Journal de Pharmacie et de Chemie. 3rd series (in French). 9: 81–91.

- ↑ Gobley, Theodore (1850). "Recherches chemiques sur les œufs de carpe" [Chemical researches on carp eggs]. Journal de Pharmacie et de Chemie. 3rd series (in French). 17: 401–430.

Je propose de donner au premier le nom de Lécithine (de λεκιθος, jaune d'œuf), parce qu'on le rencontre en grande quantité dans le jaune d'œuf … (I propose to give to the former the name of lecithin (from λεκιθος, egg yolk), because it is encountered in great quantity in egg yolk … )

- ↑ Gobley, Theodore (1874). "Sur la lécithine et la cérébrine". Journal de Pharmacie et de Chimie. 4th series (in French). 19: 346–353.

- ↑ Leslie M Fischer; Kerry-Ann da Costa; Lester Kwock; Joseph Galanko; Steven H Zeisel (2010). "Dietary choline requirements of women: effects of estrogen and genetic variation". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 92 (5): 1113–1119. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2010.30064. PMC 2954445

. PMID 20861172.

. PMID 20861172. - ↑ Leermakers ET et al. (2015). "Effects of choline on health across the life course: a systematic review". Nutr Rev. 73 (8): 500–22. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuv010. PMID 26108618.

- ↑ Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism, Sareen S. Groper and Jack L. Smith, Wadsworth pub., 2005, ISBN 9781133104056, p. 348 (Google Books)

- ↑ choline

- 1 2 Gertruida M Marx, Dissertation submitted in fulfillment of requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Free State, South Africa. December 2010. MONITORING OF GENETICALLY MODIFIED FOOD PRODUCTS IN SOUTH AFRICA

- ↑ Regulation (EC) 50/2000

- ↑ John Davison, Yves Bertheau (2007) EU regulations on the traceability and detection of GMOs: difficulties in interpretation, implementation, and compliance CAB Reviews: Perspectives in Agriculture, Veterinary Science, Nutrition, and Natural Resources 2(77)

- ↑ Scholfield, C.R. (October 1981), "Composition of Soybean Lecithin", Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society, 58 (10): 889–892, doi:10.1007/bf02659652, retrieved 2014-08-21 – via USDA

- ↑ Supplier's website with lecithin applications

- ↑ Food Uses of Oils and Fats The Lipid Handbook, Frank D. Gunstone, John L. Harwood and Albert J. Dijkstra, CRC Press, 2007, ISBN 0-8493-9688-3, page 340 (Google Books)

- ↑ Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers, Food Standards Agency, 26 November 2010

- ↑ Zeisel SH; da Costa KA (November 2009). "Choline: an essential nutrient for public health". Nutrition Reviews. 67 (11): 615–23. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00246.x. PMC 2782876

. PMID 19906248.

. PMID 19906248. - 1 2 Staff, Alternative Medicine Review (2002) Phosphatidylcholine Altern Med Rev. 7(2):150-4.

- ↑ Jackie Dial, PhD and Sandoval Melim, PhD, ND. June 2000, updated June 2003. "Lecithin" in AltMedDex® Evaluations. Truven Health Analytics.

- ↑ Higgins JP, Flicker L. Lecithin for dementia and cognitive impairment Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(3):CD001015

- ↑ Oosthuizen W, Vorster HH, Vermaak, WJ, et al. Lecithin has no effect on serum lipoprotein, plasma fibrinogen and macro molecular protein complex levels in hyperlipidaemic men in a double-blind controlled study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998;52:419-424.

- ↑ Diane Wiessinger, Diana West, and Teresa Pitman. Dealing with Plugs and Blebs from Chapter 20, "Tear sheets" in The Womanly Art of Breastfeeding. La Leche League. 2010. ISBN 0345518446

- ↑ Discussion Forum: American Academy of Allergy, Asthama, and Immunology

- ↑ Unisci.com, Why Eggs Don't Contribute Much Cholesterol To Diet.

- ↑ (Reb Yehonatan Levy, Shomer Kashrut Mashgiach - based upon halachic rulings of CRC - Chicago Rabbinic Council, and from shiurim/lessons by Rabbi D. Raccah on "Pesach Preparations" following commentary from former Rishon-LeTzion Rav Ovadia Yosef). OK Kosher Certification, Keeping Kosher for Pesach. Retrieved on September 10, 2008.

- ↑ Islamic Food and Nutrition Council of America FAQ, IFANCA: Consumer FAQ. Retrieved on July 7, 2010. The practice of consuming Halal products is not widespread among Muslims, the practice is common with Muslims who follow Sharia laws.

- ↑ Iwata T, Kimura Y, Tsutsumi K, Furukawa Y, Kimura S (February 1993). "The effect of various phospholipids on plasma lipoproteins and liver lipids in hypercholesterolemic rats". J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 39 (1): 63–71. doi:10.3177/jnsv.39.63. PMID 8509902.

- ↑ Jimenez MA, Scarino ML, Vignolini F, Mengheri E (July 1990). "Evidence that polyunsaturated lecithin induces a reduction in plasma cholesterol level and favorable changes in lipoprotein composition in hypercholesterolemic rats". J. Nutr. 120 (7): 659–67. PMID 2366101.

- ↑ Wendy R Russell WR et al. (2013) Colonic bacterial metabolites and human health (Review). Current Opinion in Microbiology 16(3):246–254

- ↑ Tang, WH; Wang Z; Levison BS; Koeth RA; Britt EB; Fu X; Wu Y; Hazen SL (Apr 25, 2013). "Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk.". N Engl J Med. 368 (17): 1575–84. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1109400. PMC 3701945

. PMID 23614584.

. PMID 23614584. - ↑ Mendelsohn, AR; Larrick JW (Jun 2013). "Dietary modification of the microbiome affects risk for cardiovascular disease.". Rejuvenation Res. 16 (3): 241–4. doi:10.1089/rej.2013.1447. PMID 23656565.

External links

- Introduction to Lecithin (University of Erlangen)

- FDA Industry guideline for soy lecithin labeling

- European Lecithin Manufacturers Association official website