Southeast Asian Massif

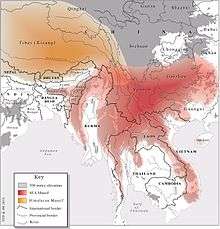

The term Southeast Asian Massif was proposed in 1997 by anthropologist Jean Michaud[1] to discuss the human societies inhabiting the lands above approximately 300 metres (980 ft) in Southeastern Asia. It concerns highlands overlapping parts of 10 countries: southwest China, extreme northeastern India, eastern Bangladesh, and all the highlands of Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar (Burma), Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. It may also be said to include the uplands of peninsular Malaysia and of Taiwan. The indigenous population encompassed within these limits numbers approximately 110 million, not counting migrants from surrounding lowland majority groups who came to settle in the highlands over the last few centuries.

The notion of the Southeast Asian Massif overlaps geographically and analytically with the eastern segment of Van Schendel's notion of Zomia proposed in 2002,[2] while it is nearly identical to what political scientist James C. Scott called Zomia in 2009.[3]

Location

As the notion refers first to peoples and cultures, it is neither realistic nor helpful to define the area precisely in terms of altitude, latitude and longitude, with definite outside limits and set internal subdivisions. Broadly speaking, however, at their maximum extension, these highland groups have historically been scattered over a domain mostly situated above an elevation of about three hundred meters, within an area approximately the size of Western Europe. Stretching from the temperate Chang Jiang (Yangtze River) which roughly demarcates the northern boundary, it moves south to encompass the high ranges extending east and south from the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau, and the monsoon high country drained by the basins of the lower Brahmaputra, Irrawaddy, Salween, Chao Phraya, Mekong, Song Hong (Red River), and Zhu Jiang (Pearl River).

In China, the Massif includes extreme eastern Tibet, southern and western Sichuan, western Hunan, a small portion of western Guangdong, all of Guizhou and Yunnan, with north and west Guangxi. Spilling over the Southeast Asian peninsula, it covers most of the border areas of Burma with adjacent segments of northeastern India (Meghalaya, Mizoram, Manipur, Nagaland with portions of Arunachal Pradesh and Assam) and southeastern Bangladesh, the north and west of Thailand, all of Laos above the Mekong valley, borderlands in northern and central Vietnam along the Annam Cordillera, and the northeastern fringes of Cambodia.

Beyond the northern limit of the Massif, the Chongqing basin is not included because it has been colonised by the Han for over one millennium, and the massive influx of population into this fertile rice bowl of China has spilled well into parts of central and western Sichuan above 500 metres. The same observation applies to highlands further north in Gansu and Shaanxi provinces. At the southern extreme, highland peninsular Malaysia should be excluded as it is disconnected from the Massif by the Isthmus of Kra, and is intimately associated with the Malay world instead.[4] That said, many of the indigenous highland populations of peninsular Malaysia, the Orang Asli, are Austroasiatic by language, and thus linked to groups in the Massif such as the Wa, the Khmu, the Katu, or the Bahnar.

The Tibetan world is not included in the Massif as it has its own logic: a centralized and religiously harmonised core with a long, distinctive political existence that places it in a "feudal" and imperial category, which the societies historically associated with the Massif have rarely, if ever, developed into.[5] In this sense, the western limit of the Massif, then, is as much a historical and political one as it is linguistic, cultural, and religious. Again, this should not be seen as clear-cut. Many societies on Tibet's periphery, such as the Khampa, Naxi, Drung or Mosuo in Yunnan, the Lopa in Nepal, or the Bhutia in Sikkim, have switched allegiances repeatedly over the centuries, moving in and out of Lhasa's orbit. Moreover, the Tibeto-Burman language family and Tibetan Buddhism have spilled over the eastern edge of the plateau.

Historical, linguistic and cultural factors

To further qualify the particularities of the Massif, a series of core factors can be incorporated: history, languages, religion, customary social structures, economies, and political relationships with lowland states. What distinguishes highland societies may exceed what they have in common: a vast ecosystem, a state of marginality, and forms of subordination. The Massif is crossed by four major language families, none of which form a decisive majority. In religious terms, several groups are Animist, others are Buddhist, some are Christian, a good number share Taoist and Confucian values, the Hui are Muslim, while most societies sport a complex syncretism. Throughout history, feuds and frequent hostilities between local groups were evidence of the plurality of cultures.[6] The region has never been united politically, not as an empire, nor as a space shared among a few feuding kingdoms, not even as a zone with harmonised political systems. Forms of distinct customary political organisations, chiefly lineage based versus "feudal",[7] have long existed. At the national level today, political regimes in countries sharing the region (democracies, three socialist regimes, one constitutional monarchy, and one military dictatorship) simply magnify this ancient political diversity.

Along with other transnational highlands around the Himalayas and around the world, the Southeast Asian Massif is marginal and fragmented in historical, economic, as well as cultural terms. It may thus be seen as lacking the necessary significance in the larger scheme of things to be proposed as a promising area subdivision of Asian studies. However, it is important to rethink country based research when addressing trans-border and marginal societies.

Inquiries on the ground throughout the Massif show that these peoples share a sense of being different from the national majorities, a sense of geographical remoteness, and a state of marginality that is connected to political and economic distance from regional seats of power. In cultural terms, these highland societies are like a cultural mosaic with contrasting colours, rather than an integrated picture in harmonized shades – what Terry Rambo, talking from a Vietnam perspective, has dubbed "a psychedelic nightmare".[8] Yet, when observed from the necessary distance, that mosaic can form a distinctive and significant picture, even if an imprecise one at times.

Historically,[9] these highlands have been used by lowland empires as reserves of resources (including slaves), and as buffer spaces between their domains. In 2009, political scientist James Scott[10] argued that there is a unity across the Massif – which he calls Zomia – regarding political forms of domination and subordination, which bonds the fates of the peoples dwelling there, virtually all of whom had taken refuge there to avoid being integrated into a more powerful state, or even allowing the very appearance of a state-like structure within their own societies. This argument had also been made, in a slightly different manner, by Dutch social scientist Willem van Schendel in 2002.[11] Van Schendel had coined the term Zomia, but its geographic coverage differs significantly from Scott's.

See also

References

- ↑ Michaud J., 1997, “Economic transformation in a Hmong village of Thailand.” Human Organization 56(2) : 222-232.

- ↑ Willem van Schendel, ‘Geographies of knowing, geographies of ignorance: jumping scale in Southeast Asia’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 20, 6, 2002, pp. 647–68.

- ↑ James C. Scott, The art of not being governed: an anarchist history of upland Southeast Asia. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009.

- ↑ Hall, A History of Southeast Asia. Tarling, The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia.

- ↑ Melvyn C. Goldstein, A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State. Berkeley: U. of California Press, 1989.

- ↑ Herman, Amid the Clouds and Mist. Robert D. Jenks, Insurgency and Social Disorder in Guizhou. The Miao Rebellion, 1854-1873. Honolulu (HA), U. of Hawaii Press, 1994. Claudine Lombard-Salmon, Un exemple d’acculturation chinoise : la province du Guizhou au XVIIIe siècle. Paris, Publication de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient, vol. LXXXIV, 1972 .

- ↑ See the Introduction in Michaud J., 2009 The A to Z of the Peoples of the Southeast Asian Massif. Lanham (Maryland), Scarecrow Press, 355p.

- ↑ A.T. Rambo, ‘Development Trends In Vietnam’s Northern Mountain Region’, In D. Donovan, A.T.Rambo, J. Fox And Le Trong Cuc (Eds.) Development Trends In Vietnam’s Northern Mountainous Region. Hanoi: National Political Publishing House, pp.5-52, 1997, p. 8.

- ↑ Lim, Territorial Power Domains. Wijeyewardene, Ethnic groups across national boundaries. Andrew Walker, The Legend of the Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma. Honolulu: U. of Hawaii Press, 1999.

- ↑ James C. Scott, The art of not being governed

- ↑ Willem van Schendel, ‘Geographies of knowing, geographies of ignorance