Southern Movement

| Southern Movement | |

|---|---|

|

Participant in the South Yemen insurgency the Yemeni Civil War, and the Yemeni Revolution | |

| |

| Active | 2007–present |

| Ideology | South Yemeni independence or autonomy |

| Leaders |

Ali Salem al Beidh Hassan al-Ba'aum Ahmed Omar Bin Fareed Abd Al-Rahman Ali Al-Jifi Saleh Bin Fareed Aidroos Al Zubaidi Shalal Ali Shayih |

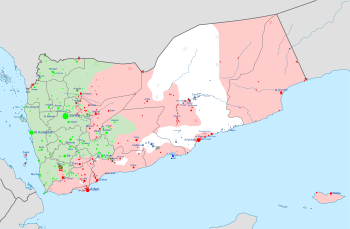

| Area of operations | Yemen |

| Part of | Popular Resistance (since 2015) |

| Allies |

Al-Islah National Army |

| Opponents |

General People's Congress (pro Saleh) |

| Website | southernhirak.org |

The Southern Movement, sometimes known as the Southern Mobility Movement, Southern Separatist Movement, or South Yemen Movement, and colloquially known as al-Hirak[1] is a political movement and paramilitary organization active in the former South Yemen since 2007, demanding secession from the Republic of Yemen.

History

After the union between South Yemen and North Yemen on May 22, 1990, a civil war broke out in 1994, resulting in the defeat of the weakened southern armed forces and the expulsion of most of its leaders, including the former Secretary-General of the Yemeni Socialist party and the Vice-President of the unified Yemen, Ali Salim al-Beidh.[2]

After the 1994 civil war and the forced national unity which followed, many southerners expressed grievance at perceived injustices against them which remained unaddressed for years. Their main accusations against the Yemeni government included widespread corruption, electoral fraud, and a mishandling of the power-sharing arrangement agreed to by both parties in 1990. The bulk of these claims were levelled at the ruling party based in Sana'a, led by President Ali Abdullah Saleh. This was the same accusation given by the former southern leaders which eventually led to the 1994 civil war.[3]

Many southerners also felt that their land, home to much of the country's oil reserves and wealth,[4] had been illegally appropriated by the rulers of North Yemen. Privately owned land was seized and distributed amongst individuals affiliated with the Sana'a government. Several hundred thousand military and civil employees from the south were forced into early retirement, and compensated with pensions below the sustenance level. Although such living standards and poverty was ripe throughout all parts of Yemen, many residents of the south felt that they were being intentionally targeted and dismissed from important posts,[5] and being replaced with northern officials affiliated with the new government.

In May 2007, southern strife took a new turn. Grieving pensioners who had not been paid for years began to organise small demonstrations calling for equal rights and an end to the economic and political marginalization of the south. As the popularity of such protests grew and more people began to attend, the demands of the protests also developed. Eventually, calls were being made for the full secession of the south and the re-establishment of South Yemen as an independent state. The government's response to these peaceful protests was dismissive, labelling them as ‘apostates of the state’ and live ammunition.[6]

This gave birth to the Southern Movement, which grew to consist of a loose coalition of groups with many different approaches, all with mainly one main aim, the majority favouring a complete secession from the north.[7]

The movement is very popular and grew across the south of Yemen,[8] especially in areas outside of the former capital Aden where government control is limited.[9] In the mountainous region of Yafa - now termed the 'Free South' or الجنوب الحر - the rule of law is imposed by a network of tribes who have all pledged allegiance to the South Yemen Movement. Just minutes outside of Aden, flags of the former South Yemen can be seen raised in the open and graffitied upon many walls, a practice which has now been made illegal by the government.[10]

In 2014–15 there was a Yemeni coup d'état by the Houthis, In February 2015 President Hadi fled to Aden, set up popular committees largely made up of people from the Southern Movement, named the Southern Resistance.[11] On the 19th March coup forces attempted to take out President Hadi.[12] The Southern Resistance defeated stationed coup forces and secured control of government buildings in Aden, as well as Aden International Airport, where they hoisted the flag of South Yemen, and bloodlessly took over police checkpoints in Ataq. Officials in Aden Governorate and several others, including Hadhramaut Governorate, said they would no longer take orders from Sana'a as a result of the coup. The Southern Movement's Southern Resistance reportedly deployed armed fighters in and around Aden to counter a "possible attack".[13][14][15]

Casualties of the movement

Although the movement claims that their aims are to be achieved through peaceful means, some of their organised protests have turned deadly. However, many southerners feel that the government's inability to control the protests or even unwillingness to compromise on their demands has led to their use of other, more violent tactics. In most cases, government forces initiated the violence by opening fire on unarmed protestors, often spawning retaliatory attacks. So far, hundreds of civilian protesters and scores of soldiers have been killed in a growing problem which has attracted the limited attention of the international community.

A government clampdown on journalists and restriction of free speech, such as the seizure of Al Jazeera broadcasting equipment,[16] means that most footage of protests and attacks comes from amateur footage uploaded onto YouTube.

A report published by the Yemeni Government said that there were 245 'protests and strikes' and 87 'bombings and shootings' in the first three months of 2010, which cost the lives of 18 civilians and wounded 120 as well as killing 10 members of the Yemeni security forces.[17]

A report by the Yemeni Ministry of Interior claimed that 254 soldiers and officers had been killed and 1,900 had been injured by the South Yemen Movement from 2009 to the first half of 2010.[18]

Southern Movement leader Brigadier General Ali Mohammed Assadi, who deserted to support the Southern rebellion in 1994 claimed that as of July 2011 there were some 1,300 "martyrs" for the Southern movement.[1]

References

- 1 2 "Is South Yemen Preparing to Declare Independence?". Time. 2011-07-08.

- ↑ Jamal S. al-Suwaidi, ed. (1995). The Yemeni War of 1994: Causes and Consequences. Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research. ISBN 0863563007.

- ↑ Carapico, Sheila; Rone, Jemera (1994). "HUMAN RIGHTS IN YEMEN DURING AND AFTER THE 1994 WAR" (PDF). Human Rights Watch/Middle East. 6 (1): 1–32. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ "North Yemeni Troops Seize Oil Field Center; Region Controls Country's Chief Resource". 1994-05-25.

- ↑ Kambeck, Jens (2016). "Returning to Transitional Justice in Yemen". Bonn: Center for Applied Research in Partnership with the Orient.

- ↑ "In the Name of Unity". 2009-12-15. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- ↑ "Yemen: End Harsh Repression in South". 2009-12-15. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- ↑ "South Yemen Activists Push For Independence". 2013-05-31. Retrieved 2016-08-11.

- ↑ "Southerners gather to demand secession on anniversary of civil war". Retrieved 2016-08-11.

- ↑ "Yemen's Separatists Call for Southern Uprising". Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- ↑ "Yemen's Southern Question During the Saudi Intervention". 2016-07-25. Retrieved 2016-08-11.

- ↑ "Yemen crisis: Air raid on president's palace in Aden". BBC News. Retrieved 2016-08-02.

- ↑ "Separatists seize police checkpoints in south Yemen city". Daily Times. 24 January 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ "Thousands protest Houthis' control of Sanaa". Al Jazeera. 24 January 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ "Separatists seize police checkpoints in Aden". Gulf News. 24 January 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ "Yemen seizes Al Jazeera equipment". 2010-03-12.

- ↑ "18 killed in south Yemen violence this year: report". 2010-04-17.

- ↑ "Yemen after Saleh: A future fraught with violence". The Muslim News. 27 May 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

External links

- The Southern Movement in Yemen, Gulf Research Center, April 2010

- Yemen's Southern Challenge, Critical Threats (American Enterprise Institute), November 2009

- Website