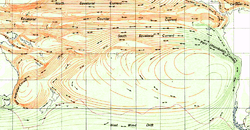

South Pacific Gyre

The Southern Pacific Gyre is part of the Earth’s system of rotating ocean currents, bounded by the Equator to the north, Australia to the west, the Antarctic Circumpolar Current to the south, and South America to the east.[1] The center of the South Pacific Gyre is the site on Earth farthest from any continents and productive ocean regions and is regarded as Earth’s largest oceanic desert.[2]

Sediment flux and accumulation

Earth’s trade winds and Coriolis force cause the ocean currents in South Pacific Ocean to circulate counter clockwise. The currents act to isolate the center of the gyre from nutrient upwelling and few nutrients are transported there by the wind (eolian processes) because there is relatively little land in the Southern Hemisphere to supply dust to the prevailing winds. The low levels of nutrients in the region result in extremely low primary productivity in the ocean surface and subsequently very low flux of organic material settling to the ocean floor as marine snow. The low levels of biogenic and eolian deposition cause sediments to accumulate on the ocean floor very slowly. In the center of the South Pacific Gyre, the sedimentation rate is 0.1 to 1 m (0.3 to 3.3 ft) per million years. The sediment thickness (from basement basalts to the seafloor) ranges from 1 to 70m, with thinner sediments occurring closer to the center of the Gyre. The low flux of particles to the South Pacific Gyre cause the water there to be the clearest seawater in the world.[2]

Subseafloor biosphere

Beneath the seafloor, the marine sediments and surrounding porewaters contain an unusual subseafloor biosphere. Despite extremely low amounts of buried organic material, microbes live throughout the entire sediment column. Average cell abundances and net rates of respiration are a few orders of magnitude lower than any other subseafloor biosphere previously studied.[2]

The South Pacific Gyre subseafloor community is also unusual because it contains oxygen throughout the entire sediment column. In other subseafloor biospheres, microbial respiration will break down organic material and consume all the oxygen near the seafloor leaving the deeper portions of the sediment column anoxic. However, in the South Pacific Gyre the low levels of organic material, the low rates of respiration, and the thin sediments allow the porewater to be oxygenated throughout the entire sediment column.[3]

Water color

Satellite data images show that some areas in the gyre are greener than the surrounding clear blue water, which is frequently interpreted as areas with higher concentrations of living phytoplankton. However, the assumption that greener ocean water always contains more phytoplankton is not always true. Even though the South Pacific Gyre contains these patches of green water, it has very little organism growth. Instead, some studies hypothesize that these green patches are a result of the accumulated waste of marine life. The optical properties of the South Pacific Gyre remain largely unexplored.[4]

See also

References

- ↑ Lovell, Clare. "Anybody home? Little response in Pacific floor." The America's Intelligence Wire 22 June 2009: n. pag. Web. 17 Oct. 2009.

- 1 2 3 D'Hondt, Steven; et al. (July 2009). "Subseafloor Sediment In South Pacific Gyre One Of Least Inhabited Places On Earth". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 11651 (6).

- ↑ Fischer, J.P., et al. "Oxygen Penetration deep into the sediment of the South Pacific Gyre" Biogeoscience (Aug. 2009): 1467(6). http://www.biogeosciences.net/6/1467/2009/bg-6-1467-2009.pdf

- ↑ Claustre, Herve, and Stephane Maritorena. "The many shades of ocean blue.(Ocean Science)." Science (Nov. 2003): 1514(2). Web. 18 Oct. 2009.