Solsbury Hill

| Solsbury Hill | |

|---|---|

|

Panoramic view on top of the hill | |

| Location | Batheaston in Somerset, England |

| Coordinates | 51°24′36″N 2°20′03″W / 51.41000°N 2.33417°WCoordinates: 51°24′36″N 2°20′03″W / 51.41000°N 2.33417°W |

| Built | Iron Age |

| Reference no. | 203323[1] |

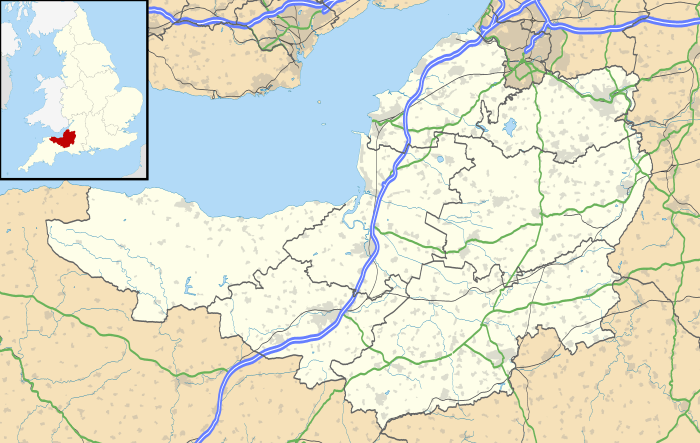

Location of Solsbury Hill in Somerset | |

Little Solsbury Hill (more commonly known as Solsbury Hill) is a small flat-topped hill and the site of an Iron Age hill fort. It is located above the village of Batheaston in Somerset, England. The hill rises to 625 feet (191 m) above the River Avon, which is just over 1 mile (2 km) to the south, and gives views of the city of Bath and the surrounding area. It is within the Cotswolds Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

The hill is one of several possible locations of the Battle of Badon and shows the remains of a medieval field system. In the 19th century part of the hill was quarried. It was acquired by the National Trust in 1930. The hill was the inspiration of the Peter Gabriel song "Solsbury Hill" which was recorded in 1977. A small turf maze was cut into the turf by protesters during the widening of the A46 in 1994.[2]

Etymology

It is sometimes misspelled as Salisbury, or Solisbury, perhaps because of confusion with Salisbury Plain (a plateau in southern England), or the city of Salisbury. Salisbury and Solsbury can be difficult to distinguish in speech, as Salisbury is often pronounced "Saulsbury" and sometimes the "a" in "Salisbury" is pronounced as an "o", and the "i" is elided, making the pronunciations of the two words practically identical.[3] The name, "Solsbury", may be derived from the Celtic god Sulis, a deity worshipped at the thermal spring in nearby Bath.[4][5]

Geology

The hill is formed in layers from a variety of sedimentary rocks of Jurassic age. In common with the Cotswold plateau to the north, the summit is formed from rocks ascribed to the Chalfield Oolite Formation. The oolite together with the Fuller's Earth Formation which underlies it, forms a part of the Great Oolite Group of rocks of Bathonian age. Beneath these are, successively, Bajocian age limestones of the Inferior Oolite Group and sandstones of the Bridport Sand Formation. The last-named unit forms a part of the Lias Group of rocks of Toarcian age. Beneath all of these is the relatively thick Charmouth Mudstone Formation sequence rising from the edge of the valley floor alluvium. All faces of the hill are subject to large areas of landslip.[6]

The 625 feet (191 m) high hill is just over 1 mile (2 km) to the north of the River Avon.[7]

Hill fort

Hill forts developed in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age, roughly the start of the first millennium BC.[8] The reason for their emergence in Britain, and their purpose, has been a subject of debate. It has been argued that they could have been military sites constructed in response to invasion from continental Europe, sites built by invaders, or a military reaction to social tensions caused by an increasing population and consequent pressure on agriculture.[9]

Solsbury hill was an Iron Age hill fort occupied between 300 BC and 100 BC, comprising a triangular area enclosed by a single univallate rampart, faced inside and out with well-built dry stone walls and infilled with rubble.[10] The rampart was 20 feet (6 m) wide and the outer face was at least 12 feet (4 m) high. The top of the hill was cleared down to the bedrock, then substantial huts were built with wattle and daub on a timber-frame.[11][12] After a period of occupation, some of the huts were burnt down, the rampart was overthrown, and the site was abandoned, never to be reoccupied.[13][14] This event is probably part of the Belgic invasion of Britain in the early part of the 1st century BC.[15]

Later history

The hill is near the Fosse Way Roman Road as it descends Bannerdown hill into Batheaston on its way to Aquae Sulis.[16][17][18] Solsbury Hill is a possible location of the Battle of Badon, fought between the Britons (under the legendary King Arthur) and the Saxons c. 496, mentioned by the chroniclers Gildas and Nennius.[19][20] The hilltop also shows the remains of a medieval or post medieval field system.[21][22][23]

The hill also has two disused quarries, one quarry listed on the North West side on an 1911 map, and another one listed as an old quarry on the West side in 1885–1900.[24] It was acquired by the National Trust in 1930.[25] People protesting against the building of an A46 bypass road[26] cut a small turf maze into the hill,[27] during the construction of the bypass in the mid-1990s.[28] In one day of protests, 11 people, including George Monbiot, were hospitalised as a result of beatings by the security guards.[29]

Wildlife

The plants and animals which live on Solsbury Hill reflect the habitat provided by grassland overlying the limestone rock beneath. Specialist plants and animals, some of which are rare species, have adapted to the calcareous grassland. Most of the landscape is largely unaffected by agriculture as shown by the yellow meadow ant.[30] Examples of plant species found include bird's foot trefoil, vetches, greater knapweed, harebells, yarrow (Achillea millefolium), and scabious. It is one of a series of flower-rich habitats, which Avon Wildlife Trust are trying to link together.[31] The plants attract a range of insects including: the six-spotted burnet moth, hummingbird hawk-moth[32] and a number of butterflies including chalkhill blues.[33] A small population of common buzzard (Buteo buteo) nest in the area.[34] Roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), badger and red fox are also seen.[35] The skylark also nests on the hill.[36]

Cultural references

Solsbury Hill is also the inspiration for rock musician Peter Gabriel's first solo single in 1977.[37] A recording of the natural sounds on Solsbury Hill forms the track "A Quiet Moment" on Peter Gabriel's 2011 album, New Blood, which precedes the orchestral version of his song.[38]

The Warlord Chronicles, a historical fiction trilogy of books, places the site of Mount Badon at Solsbury Hill.[39]

See also

References

- ↑ "Solsbury Hill". National Monuments Record. English Heritage. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ↑ "Focus on Little Solsbury Hillfort". The Heritage Journal. 22 March 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ↑ Bowles, W.L. (1828). Hermes britannicus: A Dissertation on the Celtic Deity Teutates, the Mercurius of Caesar, in Further proof and corroboration of the origin and designation of the great temple at abury in Wiltshire. J.B. Nichols and Son. p. 126.

- ↑ William Page (editor) (1906). "Romano-British Somerset: Part 2, Bath". A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 1. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ↑ Vile, Nigel (16 February 2012). "Hill is still in tune with the city's Celtic goddess". Bath Chronicle. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ↑ British Geological Survey 2011 Bath, England and Wales sheet 265 Bedrock & Superficial Deposits, 1:50,000 (Keyworth, Nottingham: British Geological Survey)

- ↑ Scott, Shane (1995). The Hidden Places of Somerset. Aldermaston: Travel Publishing Ltd. p. 16. ISBN 1-902007-01-8.

- ↑ Payne, Andrew; Corney, Mark; Cunliffe, Barry (2007). The Wessex Hillforts Project: Extensive Survey of Hillfort Interiors in Central Southern England. English Heritage. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-873592-85-4.

- ↑ Sharples, Niall M (1991). English Heritage Book of Maiden Castle. London: B. T. Batsford. pp. 71–72. ISBN 0-7134-6083-0.

- ↑ "Slight Univallate Hillfort 190m North West of Westleigh". National Heritage List for England. English Heritage. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ↑ Dowden, W.A. "Little Solsbury Hill Camp. Report on Excavations of 1955 and 1956" (PDF). Proceedings of the University of Bristol Speleological Society. 18 (1): 18–29.

- ↑ Dowden, W.A. "Little Solsbury Hill Camp. Report on Excavations of 1958" (PDF). Proceedings of the University of Bristol Speleological Society. 9 (3): 177–182.

- ↑ "Solsbury Hill". Pastscape. English Heritage. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ Tratman, E.K. "Little Solsbury Hill Camp" (PDF). Bath and Camerton Archaeological Society. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ Ciceran, Marissa. "General History of Hillforts". Istrianet. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ Codrington, Thomas (1903). Roman Roads in Britain. Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- ↑ Castleden, Rodney (2003). King Arthur: The Truth Behind the Legend. Routledge. p. 95. ISBN 9781134373765.

- ↑ Oswin, John; Buettner, Rick. "Little Solsbury Hill Camp Geophysical Survey Batheaston, Somerset 2012" (PDF). Bath and Camerton Archaeological Society. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ Baker, Mick. "The Site of the Battle of Badon: The Case for Bath". Post-Roman Britain. The History Files. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ Reno, Frank D. (1996). The Historic King Arthur: Authenticating the Celtic Hero of Post-Roman Britain. McFarland. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-7864-3025-3.

- ↑ Oswin, John; Buettner, Rick. "Geophysics on Solsbury Hill" (PDF). Bath and Camerton Archeological Society. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ↑ "Medieval fields (?) with markers Little Solsbury" (PDF). Bath and North East Somerset Council. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ "Bath and North East Somerset: Local Plan: Strategic Land Availability Assessment: Report of Findings (November,2013): Appendix 1b: Bath Green Belt" (PDF). Bath and North East Somerset Council. p. 24. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ "Ordnance Survey 1:10560 County Series 2nd edition (c.1900) Sheet 08 Subsheet 14". somerset.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ "Acquisitions Up to December 2011" (PDF). National Trust. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ Arbib, Adrian (2010). Solsbury Hill: Chronicle of a Road Protest. Oxford: Bardwell Press. ISBN 978-1-905622-20-7.

- ↑ "English Turf Labyrinths". Labyrinthos. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ "Focus on Little Solsbury Hillfort". The Heritage Journal. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ↑ "About George Monbiot". George Monbiot. 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ↑ "Hill is still in tune with the city's Celtic goddess". Bath Chronicle. 16 February 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ "A Living Landscape: The Bigger Picture" (PDF). South West Wildlife Trusts. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ "Latest sightings". Somerset Moth Group. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ↑ "Species groups with records for 'LITTLE SOLSBURY HILL'". NBN Gateway. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ↑ Fisher, Graham. "Upper Swainswick — Little Solsbury Hill — Charmy Down". Walking World. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ "Batheaston SHLAA site BES 1 – Hawkers Yard" (PDF). Bath and North East Somerset Council. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ↑ "Rural Fringe: North of Bath". Environment and Planning. Bath and North east Somerset. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ "Solsbury Hill by Peter Gabriel". Songfacts. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- ↑ "Hear Peter Gabriel's new album 'New Blood'". New Musical Express. 3 October 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ Cornwell, Bernard (2011). Warlord Chronicles. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-241-96002-8.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Solsbury Hill. |