History of slavery in New York

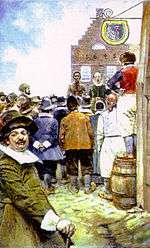

Historically, the enslavement of overwhelmingly African peoples in the United States, began in New York as part of the Dutch slave trade. The Dutch West India Company imported 11 African slaves to New Amsterdam in 1626, with the first slave auction being held in New Amsterdam in 1655. The last slaves were freed on July 4, 1827, although many black New Yorkers continued to serve as bound apprentices to their mothers' masters.[1]

The British expanded the use of slavery, and in 1703, more than 42 percent of New York City households held slaves, often as domestic servants and laborers. This was the second-highest proportion of any city in the colonies after Charleston, South Carolina.[2] Others worked as artisans or in shipping and various trades in the city. Slaves were also used in farming on Long Island and in the Hudson Valley, as well as the Mohawk Valley.

During the American Revolutionary War, the British troops occupied New York City in 1776. The Crown promised freedom to slaves who left rebel masters, and thousands moved to the city for refuge with the British. By 1780, 10,000 blacks lived in New York. Many were slaves who had escaped there from slaveholders in North and South. After the war, 3,000 slaves were evacuated with the British, most being taken to Nova Scotia for freedom.

When Vermont asserted its independence from both New York and New Hampshire, it abolished slavery within its territory.

After the American Revolution, the New York Manumission Society was founded in 1785 to work for the abolition of slavery and for aid to free blacks. The state passed a 1799 law for gradual abolition; after that date, children born to slave mothers were free but required to work for the mother's master for an extended period as indentured servants into their late twenties. Existing slaves kept their status. All remaining slaves were finally freed on July 4, 1827.

Dutch rule

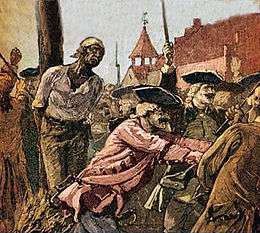

Chattel slavery in the geographical area of the present-day U.S. state of New York began in 1626, when 11 Africans were unloaded into New Amsterdam harbor from a ship of the Dutch West India Company. Before this time, the company had tried to encourage Dutch agricultural laborers to immigrate to and populate New Netherlands. This experiment was unsuccessful, as most immigrants wanted to accrue greater income in the lucrative fur trade and return to their home country in luxury.

The lack of workers in the colony, and white supremacy, led to the company's reliance on African slaves. While the slaves laid the foundations of the future New York, they were described by the Dutch as "proud and treacherous", a stereotype for African-born slaves.[3] The Dutch West India Company relaxed its monopoly and allowed New Netherlanders to ship slaves back to Angola. They began to import more numerous "seasoned" African slaves from the sugar colonies of the Caribbean.

By 1644, some slaves had earned a half-freedom in New Amsterdam and were able to earn wages. They had other rights in the commercial economy, and intermarriage with whites was frequent.[4] According to the principle of partus sequitur ventrem adopted from southern colonies, children born to enslaved women were considered born into slavery, regardless of the ethnicity or status of the father.[3]

The company turned to slavery, which was already well established in the Dutch colonies in the Caribbean, Southeast Asia, and Southern Africa. For more than two decades after the first shipment, the Dutch West India Company was dominant in the importation of slaves from the coasts of West and Central Africa. While the majority of slaves were sent to the sugar plantations of the Dutch colonies in the Caribbean, a number of slaves were imported directly from the company's stations in Angola to New Netherlands. They were used to clear forests, lay roads, and provide other heavy work and public services to the colony.

These first 11 slaves in New Netherland – owned by the Dutch East Indies Company ( called the VOC ) – were to experience a life different from other slaves in other colonies. By definition, they were owned by a master, could not leave their master, and could be bought and sold. This is different than an indentured servant who may have chosen to "indenture" themselves. This is usually when the indentured servant contracts themselves to a master for a specific length of time, after which they would be free to lead their own lives. Slaves do not have contracts, only their master determines when they will be freed. These first 11 slaves were "originally captured by the Portuguese along the West African coast and on the islands in the Gulf of Guinea,.." They were on a Spanish slave ship which would transport them to the West Indies when the VOC's navy had taken them as prizes. Many of the original New Netherland slaves have Iberian (Portuguese) names. They were given living quarters 5 miles north of the town of New Amsterdam, after which they were moved to a large building at the southern end of William Street next to the fort. "The men were employed as field hands by the Company, as well as in building and road construction and other public works projects." Women were placed as domestic servants in company official's homes. "Their servitude was involuntary and unremunerated,..." These and other slaves that followed had certain basic rights. These basic rights are related to the freedoms and rights the Dutch people in both the Netherlands in Europe and New Netherland in America enjoyed. Slaves had the right to: marry, have children, and could hire themselves out to work and earn wages during their free time. They could own "moveable" property such as pots, pans, clothes, etc., but not real estate. They could raise their own crops and animals on VOC land. But most importantly they were trusted in ways other colonies did not trust slaves. For instance, Slaves could suit another person whether white or black. Also, "They could bring suit in court and their testimony would convict free whites." The right of litigation, "On December 9, 1838, a slave known as Anthony the Portuguese sued a white merchant, Anthony Jansen from Salee, and was award reparations for damages caused to his hog by the defendant's dog. In the following year Pedro Negretto successfully sued an Englishman, John Seales, for wages due for tending hogs. Manuel de Reus, a servant of the Director General Willem Kieft, granted a power of attorney to the commas at Fort Orange to collect fifteen guilders in back wages for him from Hendrick Fredricksz." Unique to this colony was how punishment could be given to a Slave. In this case he was suited, "...in 1639 a white merchant Jan Jansen Damen, sued Little Manuel (sometimes called Manuel Minuit) and was in turn sued by Manuel de Reus; both cases were settled out of court."

These first 11 slaves and several others experienced something that was not common. The Dutch had a system for leaving slavery with three parts; Slavery, Half-Slave and Freedmen. These 11 slaves were granted partial and then full freedom. "The reasons given by Director General Kieft and the Council [who also represented the VOC] include service to the company for 18 or 19 years, a long-standing promise of freedom, 'also, that they are burdened with many children, so that it will be impossible for them to support their wives and children as they have been accustomed to in the past if they must continue in the honorable Company's service.'" This concept of "that the longer one has served, the more deserving he is of freedom", is compared to the standard of "a lifetime of servitude". Additionally, there was a sense of "Quality of life", that even a slave's child had a right to a certain standard of living was unique to the New Netherland colony. Enough so that it allowed a parent to move from slave status to half-slave or even freemen. Half-Slaves still worked for their masters when called upon, but could buy land and a home and they would now earn a wage for the work they did for their master, provided good behavior. However, there were no regulations associated with this idea. It was only practiced. Once these 11 received half-slave status, several more slaves did too. This is reflected in land grant records. Some became half-slave while others were granted freedom. After the English seized New Amsterdam in 1664, in a rush right before the English officially took over, all former slaves that were granted half-slave status were freed, so to keep the promises given to them and that the English would not keep them enslaved. The new freemen also had their original land grants finalized and all grants were officially marked as being owned by the new freemen. Freedom and land grants were given to both freed male and female former slaves. Roughly 40 slaves received their freedom prior to the English take over. Freedmen of New Amsterdam, New York State Library, Peter R. Christoph

The company turned to slavery, which was already well established in the Dutch colonies in the Caribbean, Southeast Asia, and Southern Africa. For more than two decades after the first shipment, the Dutch West India Company was dominant in the importation of slaves from the coasts of West and Central Africa. While the majority of slaves were sent to the sugar plantations of the Dutch colonies in the Caribbean, a number of slaves were imported directly from the company's stations in Angola to New Netherlands. They were used to clear forests, lay roads, and provide other heavy work and public services to the colony.

English rule

In 1664, the English took over New Amsterdam and the colony. They continued to import slaves to support the work needed. Enslaved Africans performed a wide variety of skilled and unskilled jobs, mostly in the burgeoning port city and surrounding agricultural areas. In 1703 more than 42% of New York City's households held slaves, a percentage higher than in the cities of Boston and Philadelphia, and second only to Charleston in the South.[2]

In 1708 the New York Colonial Assembly passed a law entitled "Act for Preventing the Conspiracy of Slaves" which proscribed a death sentence for any slave who murdered or attempted to murder his or her master. This law, one of the first of its kind in Colonial America, was in part a reaction to the murder of William Hallet III and his family in Newtown (Queens).[5]

As in other slaveholding societies, the city was swept by periodic fears of slave revolt. Incidents were misinterpreted under such conditions. In what was called the New York Conspiracy of 1741, city officials believed a revolt had started. Over weeks, they arrested more than 150 slaves and 20 white men, trying and executing several, in the belief they had planned a revolt. Historian Jill Lepore believes whites unjustly accused and executed many blacks in this event.[6]

In 1991, the remains of 400 Africans from the colonial era were uncovered during excavation for the Foley Square Courthouse in Lower Manhattan. Construction was delayed so the site and some of the remains could be appropriately evaluated by archeologists and anthropologists. Scholars have estimated that 15,000 to 20,000 enslaved Africans and African Americans were buried during the 17th and 18th centuries in the cemetery in lower Manhattan, making it the largest colonial cemetery for Africans in North America.

This discovery demonstrated the large-scale importance of slavery and African Americans to New York and national history and economy. The African Burial Ground has been designated as a National Historic Landmark and a National Monument for its significance. A memorial and interpretive center for the African Burial Ground have been created to honor those buried and to explore the many contributions of African Americans and their descendants to New York and the nation.[7] These sites opened in 2007, followed by a Visitor Center in 2010.

American Revolution

African Americans fought on both sides in the American Revolution. Many slaves chose to fight for the British, as they were promised freedom by General Carleton in exchange for their service. After the British occupied New York City in 1776, slaves escaped to their lines for freedom. The black population in New York grew to 10,000 by 1780, and the city became a center of free blacks in North America.[4] The fugitives included Deborah Squash and her husband Harvey, slaves of George Washington, who escaped from his plantation in Virginia and reached freedom in New York.[4]

In 1781 the state of New York offered slaveholders a financial incentive to assign their slaves to the military, with the promise of freedom at war's end for the slaves. In 1783, black men made up one-quarter of the rebel militia in White Plains, who were to march to Yorktown, Virginia for the last engagements.[4]

By the Treaty of Paris (1783), the United States required that all American property, including slaves, be left in place, but General Guy Carleton followed through on his commitment to the freedmen. When the British evacuated from New York, they took 3,000 freedmen with them for resettlement, mostly in Nova Scotia and other colonies.[4] A joint board of enquiry at Fraunces Tavern failed to find evidence of enslavement for most of the Negroes who had fought in the King's cause.

The Book of Negroes lists the 3,000 Black Loyalists who left with the British in 1783 to resettle in Nova Scotia (now Maritime Canada), England, and other parts of the British Empire. With British support, in 1793 a large group of these Black Britons moved on from Nova Scotia to create an independent colony in Sierra Leone to escape discrimination and other conditions in Canada. They were the ancestors of the Krios, Sierra Leone Creole people.

Abolition and moving forward as citizens

In the aftermath of the Revolution, men assessed slavery against the revolutionary ideals and many, in the North especially, increased their support for abolitionism. In 1781, the state legislature voted to free those slaves who had fought with the rebels during the Revolution. Abolition was not achieved for several years, but the legislature passed a law making the process of manumission easier, and numerous slaveholders individually freed their slaves.

The New York Manumission Society was founded in 1785, and worked to prohibit the international slave trade and to achieve abolition. It established the African Free School in New York City, the first formal educational institution for blacks in North America. It served both free blacks and the children of slaves. The school expanded to seven locations and produced some brilliant alumni, who advanced to higher education and prominent careers. These included James McCune Smith, who gained his medical degree with honors at the University of Glasgow after being denied admittance to two New York colleges. He returned to practice in New York and also published numerous articles in medical and other journals.[4]

By 1790 one in three blacks in New York state were free. Especially in areas of concentrated population, such as New York City, they organized as an independent community, with their own churches, benevolent and civic organizations, and businesses that catered to their interests.[4]

Steps toward abolition of slavery accumulated, but the legislature also took steps back. Slavery was important economically, both in New York City and in agricultural areas. In 1799, the legislature passed a law for gradual abolition. It declared children of slaves born after July 4, 1799 to be legally free, but the children had to serve an extended period of indentured servitude: to the age of 28 for males and to 25 for females. Slaves born before that date were redefined as indentured servants but essentially continued as slaves for life.[8]

African Americans' participation as soldiers in defending the state during the War of 1812 added to public support for their full rights to freedom. In 1817, the state freed all slaves born before July 4, 1799 (the date of the gradual abolition law), to be effective in 1827. It continued with the indenture of children born to slave mothers until their 20s, as noted above.[8] On July 4, 1827, the African-American community celebrated final emancipation in the state with a long parade through New York City.

New York residents were less willing to give blacks equal voting rights. By the constitution of 1777, voting was restricted to free men who could satisfy certain property requirements for value of real estate. This property requirement disfranchised poor men among both blacks and whites. The reformed Constitution of 1821 conditioned suffrage for black men by maintaining the property requirement, which most could not meet, so effectively disfranchised them. The same constitution eliminated the property requirement for white men and expanded their franchise.[8] No women yet had the vote in New York. "As late as 1869, a majority of the state's voters cast ballots in favor of retaining property qualifications that kept New York's polls closed to many blacks. African-American men did not obtain equal voting rights in New York until ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870."[8]

It is often overlooked how much of a role African Americans had in the movement from slavery to freedom , as well as how powerful they were in establishing their own community. The emancipation of slavery in New York was a slow, complicated, and dramatic change of law that significantly affected lives of African Americans and their families. In New York, Black abolitionists began to fight for themselves and plead their cause. Although often overlooked, African American abolitionists heavily contributed to the gradual abolishment of slavery in New York. The fight for their own people helped make the fight for freedom and equality even stronger and more powerful, changing New York and its society. African Americans played a great role in the abolishment of slavery in New York, and once free from slavery, blacks worked through many hardships in order to establish their own community. Through documentation of the abolitionists in the 1800s, as well as laws passed in that period, one can see the fight and dedication put into the effort of emancipation as well as rebuilding the black community as its own. Many times, it is forgotten that there were blacks that contributed to the change during and after the gradual abolition of slavery. It is crucial to note that both white and black protagonists hated slavery and fought for emancipation, but that the struggle was much more personal for blacks. African Americans wanted freedom just as much as the next person, and fought long and hard in order to have it. In New York, after they finally succeed in 1827, many blacks from Brooklyn needed to start their own community, bringing a new vigilance to the community. Very often, the perspective of gradual abolishment was very different from African Americans than whites. Nonetheless, the abolitionists all wanted the same thing- an end to slavery. Often times, Blacks are overlooked as abolitionists. It is true, however, that African American protagonists heavily helped not only the emancipation of slavery, but the notion of being taken seriously by the community.

Because of the gradual abolition laws, there were children still enslaved when their parents were free.[9] This caused an uprise in passion, and lead to the upbringing of more African American anti-slavery activists.[9]

Freedom, of course, did not happen as quickly as a day or two, and neither did the establishment of a new life. The fight for freedom was a long and hard fight, and once free, there was still a long process ahead in order establish a community of their own for black citizens.

The founding in New York City of the Freedom's Journal, was the nation's first African American journal in the New York Newspaper, published just months previous to the celebration of July 4, 1827. It showed what the new times were holding for America as well as its new stresses and demands.[10] Samuel Cornish and John Russwurm were editors of the journal and used it to control as much as they could.[10] The powerful words published spread rapid positive influence to African Americans who could help establish a newly-found community. The emergence of an African American authored journal in a white newspaper was a very important movement in New York. Many blacks were less educated than whites and it proved their capability of being educated.[11]

White newspapers visually exposed racism and mockery in the publication of a "Bobalition" print series, which was fictional and currupt. This was made in mockery of blacks, in that this was the way an uneducated colored person would pronounce abolition.[12]

See also

- African Burial Ground National Monument

- New York Slave Insurrection of 1741

- African Americans in New York City

- Human trafficking in New York

References

- ↑ http://slavenorth.com/nyemancip.htm

- 1 2 , The Nation, 7 November 2005

- 1 2 Douglas Harper, "Slavery in New York", Slavery in the North Website, 2003, accessed 27 September 2011

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Exhibit: Slavery in New York". New York Historical Society. October 2005. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ Wolfe, Missy. Insubordinate Spirit: A True Story of Life and Loss in Earliest America 1610-1665. Guilford CT, 2012, pages 192-194

- ↑ Jill Lepore, New York Burning; Liberty, Slavery, and Conspiracy in Eighteenth-Century Manhattan, 2005

- ↑ "African Burial Ground National Monument", National Park Service, Accessed 29 December 2007

- 1 2 3 4 "African American Voting Rights", New York State Archives, accessed 11 February 2012

- 1 2 Harris, Leslie M. In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626–1863. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003: 93–95.

- 1 2 Capie, Julia M. “Freedom of Unspoken Speech: Implied Defamation and Its Constitutional Limitations.” Touro Law Review 31, no. 4 (October 2015): 675.

- ↑ Gellman, David N. “Race, the Public Sphere, and Abolition in Late Eighteenth-Century New York.” Journal of the Early Republic 20, no. 4 (2000): 607–36.

- ↑ “In Pursuit of Freedom,” Brooklyn Historical Society, (Accessed: April 24, 2016). http://pursuitoffreedom.org/timeline.

External links

- Slavery in New York, October 2005 – September 2007, an exhibition by the New-York Historical Society

- Douglas Harper, "Slavery in New York", Slavery in the North, 2003, Official Website

- "The Hidden History of Slavery in New York", The Nation, 5 Nov 2007

- "Interview: James Oliver Horton: Exhibit Reveals History of Slavery in New York City", PBS Newshour, 25 January 2007

- Slavery In Mamaroneck Township, Larchmont Website