Silver coin

Silver coins are possibly the oldest mass-produced form of coinage. Silver has been used as a coinage metal since the times of the Greeks; their silver drachmas were popular trade coins. The ancient Persians used silver coins between 612-330 BC. Before 1797, British pennies were made of silver.

As with all collectible coins, many factors determine the value of a silver coin, such as its rarity, demand, condition and the number originally minted. Ancient silver coins coveted by collectors include the Denarius and Miliarense, while more recent collectible silver coins include the Morgan Dollar and the Spanish Milled Dollar.

Other than collector's silver coins, silver bullion coins are popular among people who desire a "hedge" against currency inflation or store of value. Silver has an international currency symbol of XAG under ISO 4217.

Origins and early development of silver coins

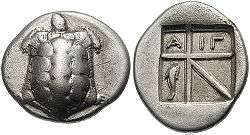

The earliest coins of the western world were minted in the kingdom of Lydia in Asia Minor around 600 BC.[1] The coins of Lydia were made of electrum, which is a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver, that was available within the territory of Lydia.[1] The concept of coinage, i.e. stamped lumps of metal of a specified weight, quickly spread to adjacent regions, such as Aegina. In these neighbouring regions, inhabited by Greeks, coins were mostly made of silver. As Greek merchants traded with Greek communities (colonies) throughout the Mediterranean Sea, the Greek coinage concept soon spread through trade to the entire Mediterranean region. These early Greek silver coins were denominated in staters or drachmas and its fractions (obols).

More or less simultaneously with the development of the Lydian and Greek coinages, a coinage system was developed independently in China. The Chinese coins, however, were a different concept and they were made of bronze.

In the Mediterranean region, the silver and other precious metal coins were later supplemented with local bronze coinages, that served as small change, useful for transactions where small sums were involved.

The coins of the Greeks were issued by a great number of city states, and each coin carried an indication of its place of origin. The coinage systems were not entirely the same from one place to another. However, the so-called Attic standard, Corinthian standard, Aiginetic standard and other standards defined the proper weight of each coin. Each of these standards were used in multiple places throughout the Mediterranean region.

In the 4th century BC, the Kingdom of Macedonia came to dominate the Greek world. The most powerful of their kings, Alexander the Great eventually launched an attack on the Kingdom of Persia, defeating and conquering it. Alexander's Empire fell apart after his death in 323 BC, and the eastern mediterranean region and western Asia (previously Persian territory) were divided into a small number of kingdoms, replacing the city state as the principal unit of Greek government. Greek coins were now issued by kings, and only to a lesser extent by cities. Greek rulers were now minting coins as far away as Egypt and central Asia. The tetradrachm (four drachms) was a popular coin throughout the region. This era is referred to as the hellenistic era.

While much of the Greek world was being transformed into monarchies, the Romans were expanding their control throughout the Italian Peninsula. The Romans minted their first coins during the early 3rd century BC. The earliest coins were - like other coins in the region - silver drachms with a supplementary bronze coinage. They later reverted to the silver denarius as their principal coin. The denarius remained an important Roman coin until the Roman economy began to crumble. During the 3rd century AD, the antoninianus was minted in quantity. This was originally a "silver" coin with low silver content, but developed through stages of debasement (sometimes silver washed) to pure bronze coins.

Although many regions ruled by Hellenistic monarchs were brought under Roman control, this did not immediately lead to a unitary monetary system throughout the Mediterranean region. Local coinage traditions in the eastern regions prevailed, while the denarius dominated the western regions. The local Greek coinages are known as Greek Imperial coins.

Apart from the Greeks and the Romans, also other peoples in the Mediterranean region issued coins. These include the Phoenicians, the Carthaginians, the Jews, the Celts and various regions in the Iberian Peninsula and the Arab Peninsula.

In regions to the East of the Roman Empire, that were formerly controlled by the Hellenistic Seleucids, the Parthians created a kingdom in Persia. The Parthians issued a relatively stable series of silver drachms and tetradrachms. After the Parthians were overthrown by the Sassanians in 226 AD, the new dynasty of Persia began the minting of their distinct thin, spread fabric silver drachms, that became a staple of their empire right up to the Arab conquest in the 7th century AD.

The Byzantine Empire, the Arabs and medieval Europe

In the Byzantine Empire, which was basically what was left of the eastern Roman Empire, the currency system was reorganised, but the coinage mostly consisted of copper and gold. A silver miliaresion was developed, usually with a cross on steps obverse and an inscription forming the reverse. Later, the cup-shaped (or 'scyphate') trachy were issued, but the silver content of these rapidly declined towards only a few per cent, finally ending up as a pure copper coin after the Fourth Crusade (13th century).

With Mohammed's revolution in the Arabian Peninsula, a new state was created in 622. After the death of Mohammed (632), the state was governed by caliphs, thus named 'the Caliphate'. As the caliphate expanded into Byzantine territories to the Northwest and conquered the Sassanian (Persian) Empire to the Northeast, the question of a caliphal coinage became imminent. The caliphate adapted the Sassanian drachm as their silver coin. Initially, Arabic inscriptions were added to the Sassanian coin type. Later, the type was completely revised, so as to include inscriptions and ornaments only. (Depictions of human beings is prohibited according to Sunni Islam). These coins are known in Arabic as dirhems. The dirhems of the caliphate gained wide acceptance. They are consequently found along trading routes in Ukraine, Russia and Scandinavia.

As the power balance within the caliphate changed (weaker central power), the names of local leaders, or feudal lords, were increasingly indicated on the dirhems. Various Arabic dynasties continued to issue dirhems for centuries after the demise of the classical caliphates. There is a great variety of types, although retaining the inscriptions and ornaments only formula.

In medieval Europe (outside the Byzantine Empire), the coinage was very complex, as the types were often different from one (small) region to another. In some regions, certain coin types became a commonly accepted coin type in inter-regional trade. For instance, the silver sceattas were a popular type of coin in England, the Netherlands and the Frisian region. The penny was a popular interregional silver coin, thus being known in several different languages as 'penny' (English), 'pfennig' (German) and 'penning' (Scandinavian languages). Medieval coin types frequently suffered from gradual debasement, and the coins were generally small. This changed when the great amounts of silver began to flow into Europe from the New World.

The Ottoman Empire and Persia

While the Byzantine Empire in the Balkans was crumbling, a new power was growing strong in Asia Minor: the Ottoman state. The Ottomans eventually conquered the Byzantine capital in 1453, creating the Ottoman Empire. Early Ottoman silver coins are the small akçes.

With the accession of the Safavid dynasty, Persia emerged as an independent state, also in terms of language and identity. This coincided with a shift from the use of Arabic to Persian in the coins' inscriptions. The coins now tended to employ cursive and interlaced script, radically altering the appearance of the coins.

India

The earliest coins of India are the so-called punch-marked coins. These were small pieces of silver of a specified weight, punched with several dies, each carrying a symbol. These very early coins were issued at a point in time when India was still separated from the Greek world by Persia (Persia proper did not use silver coins at the time).

The Sanskrit word rūpyakam (रूप्यकम्) means "wrought silver" or a coin of silver.[2] The term could also be related to "something provided with an image, a coin," from rūpa "shape, likeness, image." The word rupee was coined by Sher Shah Suri, a renagade governor who broke off from the Mughal Empire during his short rule of northern India between (1540–1545). It was used for the silver coin weighing 178 grains. He also introduced copper coins called Dam and gold coins called Mohur that weighed 169 grains.[3] Later on, the Mughal Emperors standardised this coinage of tri-metalism across the sub-continent in order to consolidate the monetary system.

Spanish America, the peso/dollar and Pacific trade

With the Spanish colonization of the Americas after 1492, there were significant finds in both New Spain (Mexico) in various sites in mainly in the zone outside indigenous settlement and in Peru, with the discovery of the great silver mine of Potosí (in modern Bolivia). The Spanish crown licensed mining sites with the provision that a fifth of the proceeds, the quinto would go to the crown. The crown established mints in Mexico and Peru, such that over the whole colonial period high quality, uniformly minted coins became the international currency. Not only did silver flow to Spain and then to Europe, enriching the Spanish crown and stimulating industries in Europe, Spanish silver coins were transported to Asia, via the Manila Galleon. China in particular preferred silver coinage and the high quality Spanish coins paid for high quality Chinese porcelains and silks and other luxury goods. Mexican silver coins continued to be exported to China in the late nineteenth-century.

Silver coins of Europe

Silver mining began early when the Americas were at its simple beginnings, also known at this time as the "New World." Europeans quickly began to exploit the silver mines, particularly those in South America, to answer a demand for silver in Europe inspired by the fine craftsmanship of the Renaissance.[4] The discovery of silver in Joachimsthal also gave rise to the silver joachimsthaler coin. Production of silver in the Americas influenced trade and politics in Europe and transformed European relations with other regions of the world, particularly China and the Ottoman Empire. The influx of silver into Europe led to the sometimes uncontrolled minting of coins. All countries of Europe eventually began to issue large size silver coins. Europeans then used these silver coins to purchase goods abroad which eventually led to inflation.[5] The great amounts of silver available caused the relative value of silver to drop.

Recent silver coins

With the reduced or even non-existent link between the value of the currency and the value of precious metals since the Great Depression of the 1930s, silver gradually ceased to be used in the manufacture of ordinary circulating coins. For this reason, silver coins are mainly either special commemorative coins minted for sale to coin collectors or bullion coins primarily sold to investors that, although legal tender, are not expected to circulate. Anything pre1964 in dimes and quarters are 90% silver. Nickels from 1943-1945 are 35% silver along with some 1942.

Bullion coins

The most common world silver bullion coins, preceded by minimum guaranteed purity, and ordered by their year of introduction:

- 99.90% 1982 Mexican Silver Libertad

- 99.90% 1983 Chinese Silver Panda

- 99.90% 1986 American Silver Eagle

- 99.99% 1988 Canadian Silver Maple Leaf

- 99.90% 1990 Australian Silver Kookaburra (minted by the Perth Mint)

- 99.90% 1993 Australian Silver Kangaroo (minted by the Royal Australian Mint)

- 95.80% 1997 British Silver Britannia (from 1997, proof version only. Public issue from 1998)

- 99.90% 2008 Austrian Silver Vienna Philharmonic

- 99.90% 2009 Russian George the Victorious

Silver rounds

Privately minted silver coins are commonly called "silver rounds" or "generic silver rounds". They are called "rounds" instead of "coins" because the US Mint reserves the use of the word "coin" for Government Issued circulating currency, such as all common coins and the American Silver and Gold Eagles. The privately minted "rounds" usually have a set weight of 1 troy ounce of silver (31.103 grams of 99.9% silver), with the dimensions of 2.54 mm thick and 39 mm across. These carry all sorts of designs, from assayer/mine backed bullion to engravable gifts, automobiles, firearms, armed forces commemorative, and holidays. Unlike silver bullion coins, silver rounds carry no face value and are not considered legal tender.

Evolution

Silver coins have evolved in many different forms through the ages; a rough timeline for silver coins is as follows:

- Silver coins circulated widely as money in Europe and later the Americas from before the time of Alexander the Great until the 1960s.

- 16th - 19th centuries: World silver crowns, the most famous is arguably the Mexican 8 reales (also known as Spanish dollar), minted in many different parts of the world to facilitate trade. Size is more or less standardized at around 38mm with many minor variations in weight and sizes among different issuing nations. Declining towards the end of the 19th century due the introduction of secure printing of paper currency. It is no longer convenient to carry sacks of silver coins when they can be deposited in the bank for a certificate of deposit carrying the same value. Smaller denominations exist to complement currency usability by the public.

- 1870s - 1930s: Silver trade dollars, a world standard of its era in weight and purity following the example of the older Mexican 8 Reales to facilitate trade in the Far East. Examples: French Indochina Piastres, British Trade Dollar, US Trade Dollar, Japanese 1 Yen, Chinese 1 Dollar. Smaller denomination exists to complement currency usability by the public.

- 1930s - 1960s: Alloyed in circulating coins of many different governments of the world. This period ended when it was no longer economical for world governments to keep silver as an alloying element in their circulating coins.

- 1960s - current: Modern crown sized commemoratives, using the weight and size of the old world crowns.

- 1980 - current: Modern silver bullion coins, mainly from 39mm - 42mm diameter, containing 1 troy ounce of pure silver in content, regardless of purity. Smaller and bigger sizes exist mainly to complement the collectible set for numismatics market. Some are also purchased as a mean for the masses to buy a standardized store of value, which in this case is silver.

Why silver is used for coinage

Silver coins were among the first coins ever used, thousands of years ago. The silver standard was used for centuries in many places of the world. And the use of silver for coins, instead of other materials, has many reasons:

- Silver is liquid, easily tradable, and with a low spread between the prices to buy and sell. A low spread typically occurs when an item is fungible.[6]

- Silver is easily transportable. Silver and gold have a high value to weight ratio.

- Silver can be divisible into small units without destroying its value; precious metals can be coined from bars, or melted down into bars again.

- A silver coin is fungible: that is, one unit or piece must be equivalent to another.

- A silver coin has a certain weight, or measure, to be verifiably countable.

- A silver coin is long lasting and durable. A silver coin is not subject to decay.

- A silver coin has a stable value and an intrinsic value. Silver has been an ever rare metal.[6]

- Because silver is not nearly as valuable as gold, it is much more practical for small everyday transactions.

Silver coins in popular culture

A silver coin or coins sometimes are placed under the mast or in the keel of a ship as a good luck charm.[7] This tradition probably originated with the Romans.[8][9] The tradition continues in modern times, for example, officers of USS New Orleans placed 33 coins heads up under her foremast and mainmast before she was launched in 1933 and USS Higgins, commissioned in 1999, had 11 coins specially selected for her mast stepping.[10]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Silver coin. |

- Euro gold and silver commemorative coins

- Gold coin

- Millesimal fineness

- Precious metal

- Silver

- Silver as an investment

- Store of value

References

- 1 2 "The origins of coinage". britishmuseum.org. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- ↑ etymonline.com (September 20, 2008). "Etymology of rupee". Retrieved 2008-09-20.

- ↑ Mughal Coinage at RBI Monetary Museum. Retrieved on May 4, 2008.

- ↑ "Silver". Guide to Gems. Credo Reference. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ "Silver". Encyclopedia of World Trade From Ancient Times to the Present. Credo Reference. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- 1 2 Hommel, Jason. "Silver Coin Proposal". SilverStockReport.com. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- ↑ Eyers, Jonathan (2011). Don't Shoot the Albatross!: Nautical Myths and Superstitions. A&C Black, London, UK. ISBN 978-1-4081-3131-2.

- ↑ Carlson, Deborah N. (2007-02-02). "Mast-Step Coins among the Romans". International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 36 (2): 317–324. doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.2006.00132.x.

- ↑ "Lucky coin found in medieval ship". BBC News. 2006-02-06. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ↑ "Boating Encyclopedia:Coin Under Mast". Answers.com. Retrieved 2010-02-26.